Most sports go through periods of change for whatever reason. Sometimes, these changes are to liven things up when things get a little stale, or as a response when it is perceived that the public is losing interest. Other times it’s driven by sponsors or participants mounting publicity campaigns to try and recoup some of the monies invested in the particular sport. Motor racing, over the years, has seen many changes in all formula of the sport. Today’s Formula One appears far more contrived than the heady “golden eras” of years gone by. DRS and double points all trying to keep television audiences watching as the latest Grand Prix season unfolds. Throughout its history, sports car racing has gone through many transformations as well. Like the others, these various changes were intended to keep manufacturers, sponsors, drivers and yes, even the spectators, tuned in and turned on to the on-track spectacle.

The IMSA GT series is a prime case in point. Founded in 1969, the original idea was to have a series of races for classes of GT and Touring cars, and it enjoyed immediate success from its very first race at Virginia International Raceway. It was the Peter Gregg and Porsche show in these early years, as they first made their mark and then dominated the series in a manner similar to the “Bruce and Denny Show” in Can-Am. However, when a series devolves to the point where it becomes a foregone conclusion as to which car and driver combination will win races before a flag has even dropped, it’s usually time for a change and a reevaluation of the rules.

From 1981 through to 1993, in an effort to spice things up, the Grand Touring Prototype (GTP) category was born to accommodate the new Group C cars from the World Endurance Championship (WEC). While keeping to the Group C constraints, the new GTP cars were not to be restricted by fuel consumption. Some of the prominent drivers of the day—most notably Derek Bell, who enjoyed the power and performance that the Group C rules allowed—were dismissive of the WEC rules, which erred on fuel economy. The freedom of unrestricted fuel in the GTP category really appealed to Bell—a true die-hard racer.

The small, but world renowned, Lola company based in Huntingdon, England, produced the first GTP series-winning car, the T600, driven by Brian Redman. Following a bad testing accident, however, Redman’s career had been on the wane, so this GTP proved to be the right opportunity, at the right time to let those in motorsport know he was back. Brian had a wealth of sports car racing knowledge under his helmet—winning races such as the Targa Florio, Sebring 12 Hours and Spa 1000K—and GTP would be another trophy for the Redman collection.

Our profiled car owes much its DNA to this previous model, therefore let’s put everything into perspective to see how it came to fruition. The T600 was designed by Lola company founder Eric Broadley, and it was the first sports car he’d worked on since the very successful Lola T70 that began life during the 1960s. Broadley was ably assisted in his quest by Lola’s project engineer, Andrew Thorby. Shape-wise the Lola T600, a full ground-effect car, was basically two parallel pontoons, which accommodated twin 60-liter fuel bladder tanks, sandwiching the cockpit and engine bay. Frenchman Dr. Max Sardou, who some argue discovered ground-effects long before Colin Chapman and who worked on the Ariane rocket, was called in to design the underside of the car. IMSA rules at the time allowed the venturi to start under the cockpit floor. The venturi diffuses air traveling under the car, generating a low pressure area beneath and creating downforce that increases the grip level. Sardou’s design was further refined following wind-tunnel testing at Imperial College London (Sardou also worked on the March 82G and the Rondeau M482). As the car was to be sold as a rolling chassis, it was not designed to take any particular engine, but its full-length monocoque allowed the insertion of a variety of engines so that each customer could choose depending upon his financial ability or favored choice. Honeycomb construction with sheet aluminum, bonded and riveted, was employed with pick-up points for engine mounting. While the bodywork was made of glass reinforced polyester (GRP), customers were aware of the new lighter carbon fiber material, a much more expensive option, which was making its initial impact in racing circles—again, as allowed by a customer’s budget.

The first cars were sold to Cooke-Woods Racing by Lola’s U.S. agent, Carl Haas, with Redman as driver, and he rewarded the team with four outright victories and the series title to arrest the grip that Porsche’s 935 had maintained in previous years. The following year there was more success with Ted Field’s Interscope team having three 5.7-liter Chevy-powered cars taking five victories at Riverside, Laguna Seca, Daytona (twice) and Pocono. However, in 1982, Porsche flooded the series with 935s to try and claw back “their title,” although it has to be said that strong opposition also came from the new March 82G.

Lola’s success led other manufacturers to become interested in the new racing formula. Jaguar—under the guidance of canny Scot Tom Walkinshaw—had been rewriting the rules of long distance sports car racing in Europe, where such contests had once been perceived as marathons rather than sprints. The Walkinshaw way was to make the races long distance sprints—full power, flat out, all the way. March, as noted, was another manufacturer who got in on the act, supplying customer cars for private entrants, winning the GTP category in 1983 with Al Holbert and in 1984 with the infamous Randy Lanier at the wheel, whose team was spuriously funded by drug dealing.

General Motors could see the marketing possibilities for joining the series. Its strategy was to use the racing series to promote the new V6 engine that was to replace their much loved V8. Asking V8 customers to accept V6 power was looking like a “bridge too far,” but success on the track would silence any dissenters. While they wished to join the IMSA GTP series, it was necessary to compete at a very high level and to be on par with the likes of Jaguar, Porsche and other marques in order for this marketing ploy to succeed. The expertise of a proven racing organization to design and prepare the cars was paramount.

To give some idea of the lengths GM was willing to go, it has to be remembered that at that time, GM power plants had been successfully used in most forms of motor racing, but it had avoided direct participation. From the late 1920s until this point in time, there had been only a couple of exceptions. The first, in 1957, when Chevrolet’s Zora Arkus-Duntov constructed the Corvette SS, which only appeared at Sebring. Another, the Corvette Grand Sport, a lightweight version of the Stingray built for FIA GT racing in the mid-1960s.

Consequently, making this decision was considered a very bold step indeed, something nearing monumental given the company’s past history. Lola had won with its T600 in the inaugural series and had assissted Mazda, too. A T610 chassis to accommodate Cosworth’s V8 DFL engine was an upgrade of the aging T600, and Broadley sold Mazda four Lola T616s, Group C2 cars, for BFGoodrich to race in 1984—seizing an opportunity to promote its new radial tires.

So, the deal was done, and it was Eric Broadley who was given the task of putting pen to paper. The plan was for GM to test and develop an old T600 fitted with a Chevrolet V8, while the build of the first of two new chassis—to be known as the T710 and T711—were taking shape. They would be powered either by the Chevrolet V8, or the Buick V6. The first car was initially set for testing and development, and would be ready for late 1984 or early 1985.

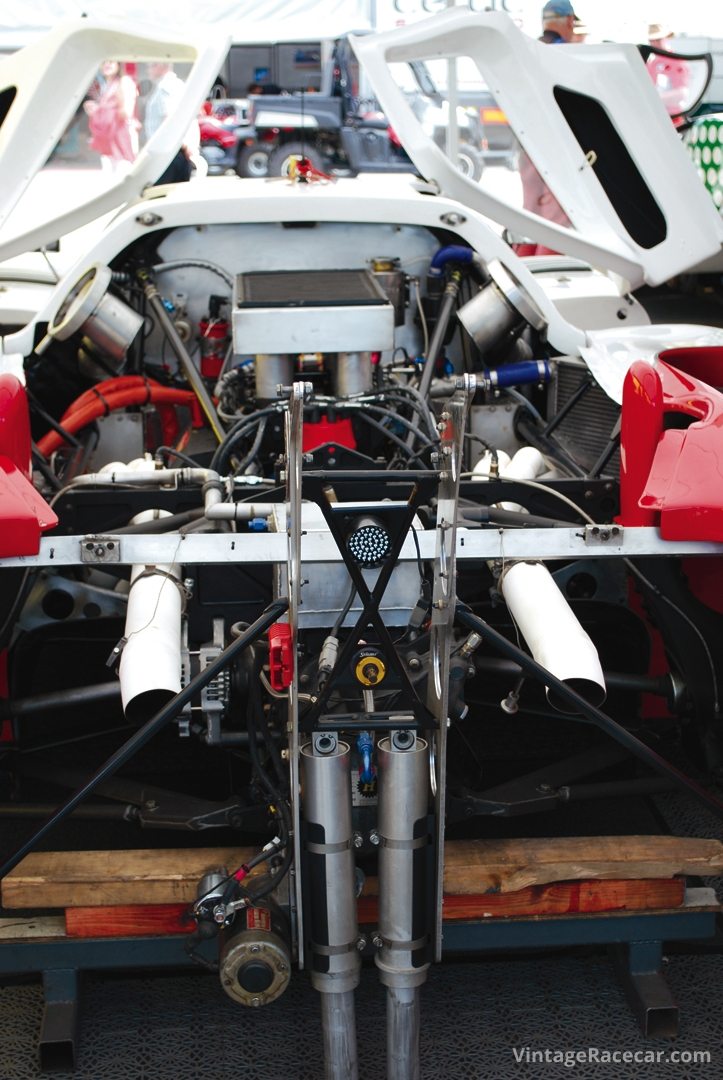

General Motors wanted to put its particular design stamp on their car, so Broadley and his team worked on the chassis and GM looked after the bodywork. Although constructed very similarly to the Lola T600, the T710 and T711 cars would have completely new monocoques made from honeycombed aluminum and designed for the T710 to take a V6 turbo engine and the T711 to take a naturally aspirated V8 power unit. This design would also allow for engines from other manufacturers as well, so that the chassis could be sold to other customers. The fuel tank, of 120-liter capacity, was centrally located between the firewall and the back of the cockpit, and the monocoque extended rearward to encompass the fuel tank and offer anchorage points for the front plate of the engine, thus adding to the torsional rigidity of the car. On the back of the engine, a Hewland 5-speed gearbox was fitted, the T710 version receiving a new bellhousing designed to accommodate the turbo V6 unit. Substantial A-frames, designed to support the weight of the engine and gearbox, protruded back to a crossmember that carried the rear shock absorbers. The rear suspension thinking was straightforward, with a conventional wishbone layout carrying outboard coil-sprung damper units mounted directly to the cast uprights.

The sides of the body sported large air intakes to aid normal engine cooling, on the left oil and ventilation to the engine bay, and on the right a large-capacity water radiator. However, on the T710, extra ducting was fitted to the top left side to aid the turbo intercooler. Moving to the front, unlike the rear suspension, the front showed more technical advancement for the time, in that a pushrod system with shock absorbers, centrally mounted in a vertical position, was employed—a technology that has become commonplace today, although modified from this first thinking.

Like the T600, GM would take charge of the body styling within the constraints of the IMSA/Group C rules. With an eye toward showroom sales, GM attempted to mirror the styling of the Corvette C4 roadcar when viewed from the front. The conventional thinking was that the nearer the car on the track looked to the road-going version, the better it would sell as the racer gained success.

Chassis T711-HU02

Although, once in America, the news was very encouraging with chassis T710, GM continually confused Broadley, as their decision to go racing was delayed time after time. He had now completed the second car (chassis T711), but it appeared that GM didn’t want to take it at this stage. It is reported that Broadley’s frustrations boiled over, as the costs for this second chassis had to be met one way or another. Lola, while a good engineering company, was living very much “hand to mouth” when it came to matters of a financial nature—it could be said the company was quite fragile on the monetary front. When Brian Redman first raced the T600 at Laguna Seca in 1981, Carl Haas told him: “If this car doesn’t win, it could bankrupt Lola.” So, Lola chassis T711-HU02, to give it its formal title, was sold to U.S. racer and businessman Lew Price and his Lee Racing Team of Pennsylvania in late 1984. Price was president of Lee Industries, a very successful company in the manufacture of ball valves. He had been a former Vice President of Operations with the company until a management buyout left him at the helm. The team had plans to compete in the 1985 Daytona 24 Hours, which they did, resulting in chassis T711 becoming the first Corvette GTP car to be entered into a race.

While the chassis design and layout of T711 was the same as T710, the car, as noted, was fitted with a naturally aspirated power unit, a 6-liter, fuel-injected V8. Like the sister car, it showed great promise in initial testing, which was encouraging to Price and his team, which it should be said were not a top-tier outfit. A more vigorous testing program was put in place in the weeks leading up to the Daytona race, and this is when the “cracks” started to appear.

For some reason, the rear of the car didn’t seem as stable as it should have been, and generally it was plagued with engine mount breakages. While testing at Daytona, Price was at the wheel travelling at some 200 mph exiting Turn 4, when all of a sudden, the rear wing detached itself and the car jolted sideways down the track. Body panels flew off as the onrushing wind played havoc—the next things to go were the doors and the windshield! Luckily, Price remained in some level of control until the car came to a standstill. At this point, only the top body section remained in position! Thankfully, Price himself was physically none the worse for the experience. The plucky little team simply recovered the stricken car and rebuilt it in time to race. Price’s teammates were Carson Baird, who had first raced at Daytona in the late 1960s, and reigning NASCAR champion Terry Labonte. A qualifying time of 1:41.490 left them in an encouraging 12th place on the grid. On February 3, 1985, the new Lola T711 took the start at the Daytona 24 Hours, uniquely becoming the very first Corvette GTP to run in competition. However, the race took its toll on the car’s debut so that the team completed only 160 of the 703 laps, finishing in 51st and not running at the flag.

Next it was on to Miami, and the team rallied to try and build on the successful qualifying effort at Daytona, with former Formula Atlantic racer Chip Mead, joining Baird. They qualified down in 20th position, but managed to finish 7th—perhaps things were moving in the right direction.

A month later at Sebring, with Labonte and Baird doing the driving, the car qualified 9th and retired after just 27 laps. Failure to finish seemed the order of the day for the following three races at Charlotte, Mid-Ohio and Watkins Glen. Fortunes for the team seemed to be on the up at the September race again at Watkins Glen, however, and in fact this race also included the sister car, chassis T710-HU01, now in the hands of Hendrick Motorsports and driven by David Hobbs and Vern Schuppan. With Price and Baird sharing the drive, they could only qualify in 16th, while Hobbs and Schuppan were 7th on the grid, but the race went better for Lee Racing with an 8th-place finish that brought encouragement and delight for them finishing so high up in a 52-car field. Hobbs and Schuppan failed to finish.

The final race of the year followed another disappointment at Columbus. Back at Daytona, Price and Baird were joined by Mead for the race where a 15th grid spot was the springboard for a 10th-place finish for this hard working, fully independent team. It was a great finish to a year that started with so much promise only to disappoint on many occasions due to mechanical and other failures. The 1986 season brought the demise of the car with three DNFs at Daytona (engine), Miami (accident) and a swansong race at Sebring where the car caught fire. The car was then “moth-balled” for a long period of time.

Price eventually sold the Lola T711 to good friend Dennis Kazmerowski of Eagle Performance Parts. Some documentation suggests this is the car, rebadged as an Eagle/EPP, which Kazmerowski, with teammates Paul Canary (who was the finance behind the project) and John Greenwood tried, but failed to qualify for the 1990 Le Mans 24 Hours. At Le Mans, the engine gave trouble and the car was way off the pace throughout qualifying. However, other documentation suggests that the Le Mans car was a later Corvette GTP chassis and not the T711.

Dave Force, of Race Ready Technologies, was the next owner of the car and put it through his workshop for a full nut and bolt restoration. It was used in Historic GTP races in the U.S. with a number of wins. From there the current owner purchased this T711 in 2008 and raced it at the Phillip Island Circuit, in Australia, in 2009 and 2010. However, the car took most of the meeting to set up and was very time-intensive to prepare. Believing it needed to run more than once a year, and that he’d actually bought a “monster” the car was again mothballed until a reappearance at the 2014 Le Mans Legends race for historic Group C racing cars, a precursor to the main 24-hour race.

Driving the Lola T711

As one approaches the car, it is obvious by its styling and presence that this is an all-American car—despite its British heritage! The bones and structure, developed in the UK, are hidden by an all-enveloping carbon and Kevlar skin. The Corvette name sits proud on the windshield, as the chorus lyrics of the country and western Corvette Song by George Jones spring to mind.

She was hotter than a two-dollar pistol

She was the fastest thing around

Long and lean, every young man’s dream

And she turned every head in town

Although this song is ambiguous in meaning there is no ambiguity about this car, which looks every inch a racer as it proudly stands on Silverstone’s tarmac, truly turning many heads. The Beach Boys, too, wrote many songs attributed to fast cars and the warm California weather. With temperatures soaring into the 90s it is difficult to rationalize that we are actually in the UK! So, with West Coast American-like sunshine, an all-American fast car and being at one of the fastest circuits in the world, all is set for a unique test.

Side on, the profile is a simple wedge, rising from a slim sharp front end, designed to cut into the oncoming air, back to a high point over the rear wheels, then it drops toward the extended tail. A large, profiled rear wing necessary to aid downforce sits centrally fixed. The shape is emphasized by the red lower paintwork starkly contrasting with the white upper livery. Externally too, the large side air intakes are very apparent, as are other cooling apertures and protrusions for front and rear brakes and the engine bay. Although static at the moment, while employed at top speed this must be some hot vehicle!

Entering the cockpit, it is the usual snuggly fitting, reclined driver’s seat offset to the right, allowing space for a left seat, as per Group C/IMSA regulations. The large windshield gives a good frontal vista, while the small rear view mirrors, which look very fragile in construction, offer adequate vision while static, but at speed on an undulating track will no doubt be considerably compromised. From the driver’s seat the cabin looks usually stark, but all dials and switches affixed to the dash panel are easy to read and operate. Somewhat nervously sitting, silently, before the ignition procedure begins there’s a feeling of anticipation of being transported back to the heady days of ultimate speed and power, which both the FIA Group C and IMSA GTP years portrayed by the bucket full.

When the engine fires into action, the whole chassis shakes and then throbs as one waits for fluid temperatures to rise to optimum driving levels. With hot ambient conditions it’s not long before the all-clear is given to roll. A forceful but precise action is required to get the car into gear. Great care has to be given to the 5-speed Hewland box, as it’s so easy to grind an edge causing considerable and expensive damage. As soon as the wheels start to roll it’s out of first and into second. Adhesion to the track is the next issue as the wide tires struggle for grip at less than working temperature—you can be off into the kitty litter in a heartbeat if you don’t respect the cold tires.

After the initial test lap, one can gather extra speed little by little, ever-decreasing lap times, as the whole car gets ready to do the business. By midway through the second lap of the Silverstone Grand Prix circuit you can really start to “get on it.” Basically, the driving of this car is no different to any other ground-effect car, keep your right foot well planted down to obtain maximum downforce. The car needs precise and definite driving actions, there’s no time to dither, or be half-hearted. For example, when approaching a slower car on the track one has to be cognizant of your own limited rear visibility. Those fragile rear view mirrors are just a blur now as the car vibrates. Unless there is a point where you can simply accelerate by, it’s best to show yourself to the car in front by drawing alongside and making him aware of your presence and intentions.

When the time is right, go for it, no time for indecision, make that pass! Like the throttle, the brakes need flat to the floor movement. Coming into a corner at full chat it’s amazing, even with steel brakes, how late you can leave it. This is the most exhilarating experience of driving this car. Some cars are really heavy and need early braking to negotiate a corner, this car is totally the opposite. You go from maximum full bore on the throttle, to maximum full bore on the brake, as you do this the car begins to lift and it’s at this point you analyse just how much you need to slow down to negotiate the bend, remembering all the time the slower you’re traveling the less grip you have. Too slow, and you’re off, too fast and you overshoot and find yourself part of the scenery. It’s a delicate, precise and definite driving style you have to adopt here, much different to many other racing cars—tremendously satisfying though, if you can get it absolutely perfect. The lightness of the car as a whole, together with the correct setup, ensures there’s no pull to the left or right under heavy braking loads. While appearing difficult, it’s a simple matter of keeping the car down for maximum grip and adhesion to the track—do that and you’ll be fine. At the conclusion of this drive it seemed so strange that the car didn’t work well straight out of the box—all the necessary ingredients are here.

SPECIFICATIONS:

Chassis: Aluminum Monocoque

Wheelbase: 106.5 inches

Length: 188 inches

Width: 79 inches

Height: 41 inches

Weight: 2200 pounds

Body panels: Kevlar/carbon

Steering: Rack and Pinion

Track: Front: 63 inches / Rear: 61 inches

Engine: 6-liter Chevy V8, naturally aspirated / 650bhp

Gearbox: Hewland VG 5-speed transaxle. 3.10:1 ratio

Wheels: (In period 16-inch) BBS 17-inch front / 18-inch rear; 11-inch front / 14-inch rear

RESOURCES:

Directory of Worldsportscars Group C and IMSA cars from 1982

by Michael Cotton

Corvette GTP

by Alex Gabbard

Autosport and Motor Sport periodicals

www.sportsracingcars.com and www.registryofcorvetteracecars.com

Sincere thanks to;

Paul Stubber for the use of his Lola T711.

Robin and his team at Damax Ltd.

Zoe Copas of Group C Racing.