1929 Bentley Blower

This Profile may be forced to veer somewhat from our usual format since the chance to have a close encounter with a very historic Bentley in the same place where it made its name and on the much heralded occasion of Team Bentley’s return to the Sarthe, rather overwhelmed the experience. This wasn’t so much a car test as a drift in time – a union of old and new. It truly got the adrenalin pumping.

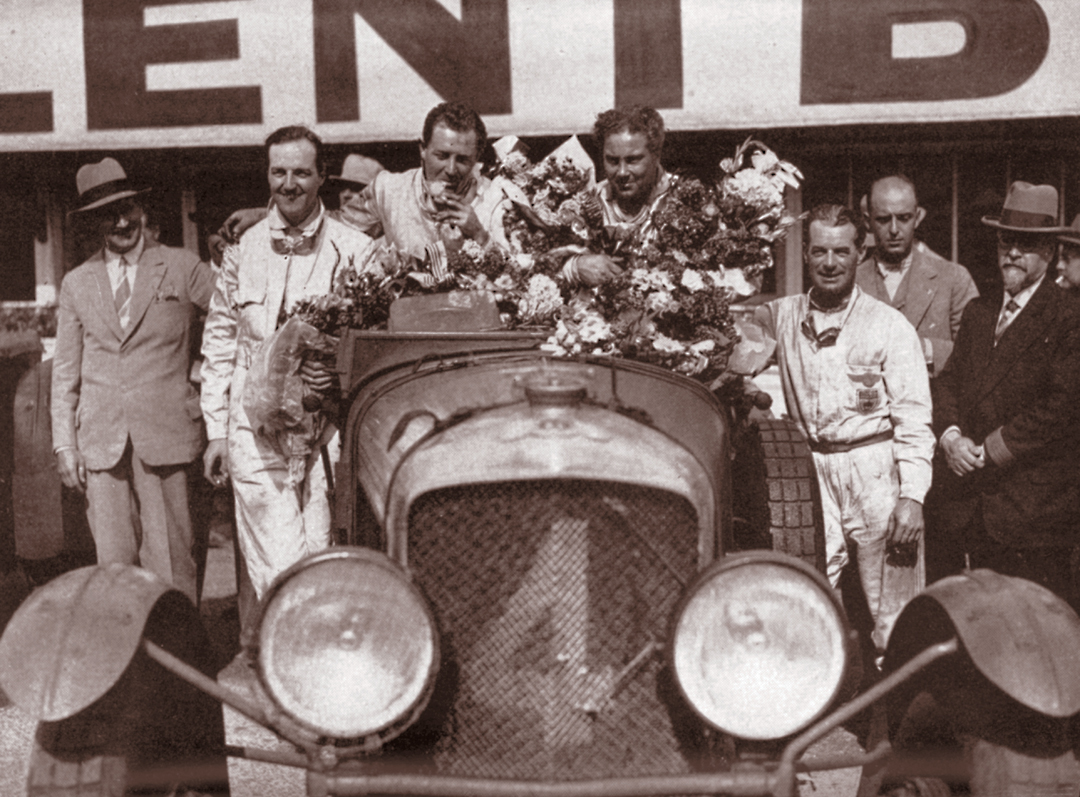

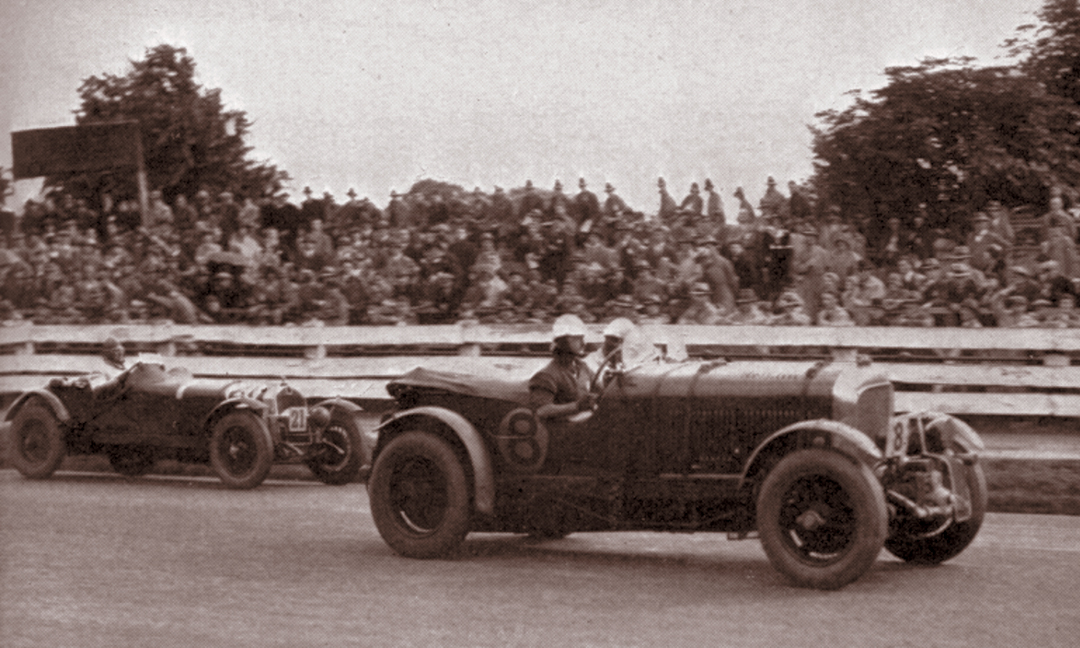

The cynics will be quick to point out that the two Bentley Exp Speed 8s, comprising all of the FIA LM GTP class, were really little more than last year’s Audis. But sitting on seventh and nineth spot on the grid for the 2001 24-Hours of Le Mans amongst the other cars, resplendent in dark green, they looked nothing short of great, and a third place finish for the number 8 car was a fair reward in atrocious conditions. But Bentley was at Le Mans in force and style with old “Number 2,” our feature car, in a place of honor in the Bentley hospitality center, along with the massed ranks of period Bentleys in the historic race paddock and out in the public car parks.

Bentley at Le Mans

Bentleys have run at Le Mans on 14 occasions from 1923 until 1951 and have taken five victories. That was a total of 30 cars, but 16 of those were present for the years 1927-1930, and those were truly the years of the “Bentley Boys,” a small band of mainly wealthy amateurs who competed not for money, but for the sheer glory and bravado of it. This bunch started with John Duff, in 1923 but really gained momentum and fame when they were joined by Woolf Barnato in 1925. W.O Bentley – or “WO,” as he was known – persuaded Barnato to buy into the company with a portion of his African diamond wealth. As a major shareholder, he brought considerable funds to the racing department and subsequently Bentley motor racing seriously got off the ground – as did the legend of the Bentley Boys and the great green cars. Ettore Bugatti, in the well-known cliché, dismissed them as trucks, which is inaccurate. “WO” had his background in rail engineering and he brought this solid but conservative approach to cars, so they weren’t trucks… they were trains!

Photo: Peter Collins

“WO” couldn’t have designed a Bugatti because of his background, much as Enzo Ferrari, son of a blacksmith, couldn’t have designed a Lotus. Bentleys were always big and solid, the pinnacle of British engineering, and these qualities proved themselves and Bentley’s ideas by winning at Le Mans.

Henry “Tim” Birkin had a considerable and unexpected influence on “WO,” he inspired the concept of supercharging in Bentleys – something that “WO” really didn’t care for – but it did bring about yet another legend, the Blower Bentley. Birkin is widely regarded as the best British driver of his day. He was an intense and restless man, bored with postwar Britain and drawn to racing, where he truly found his place. He had driven a 4-liter Bentley in Ireland, France and Germany in 1928, when he came up with the idea of supercharging it. “WO” was not keen on the idea, as he sought reliability in everything he did, and he didn’t want to stake his reputation on something fragile. Hence he ran three of the 6.5-liter Speed Sixes at Le Mans in 1930 as well, and they repaid him with first and second. Birkin had shared the winning Speed Six with Barnato in 1929, but had been pushing for something more powerful for 1930.

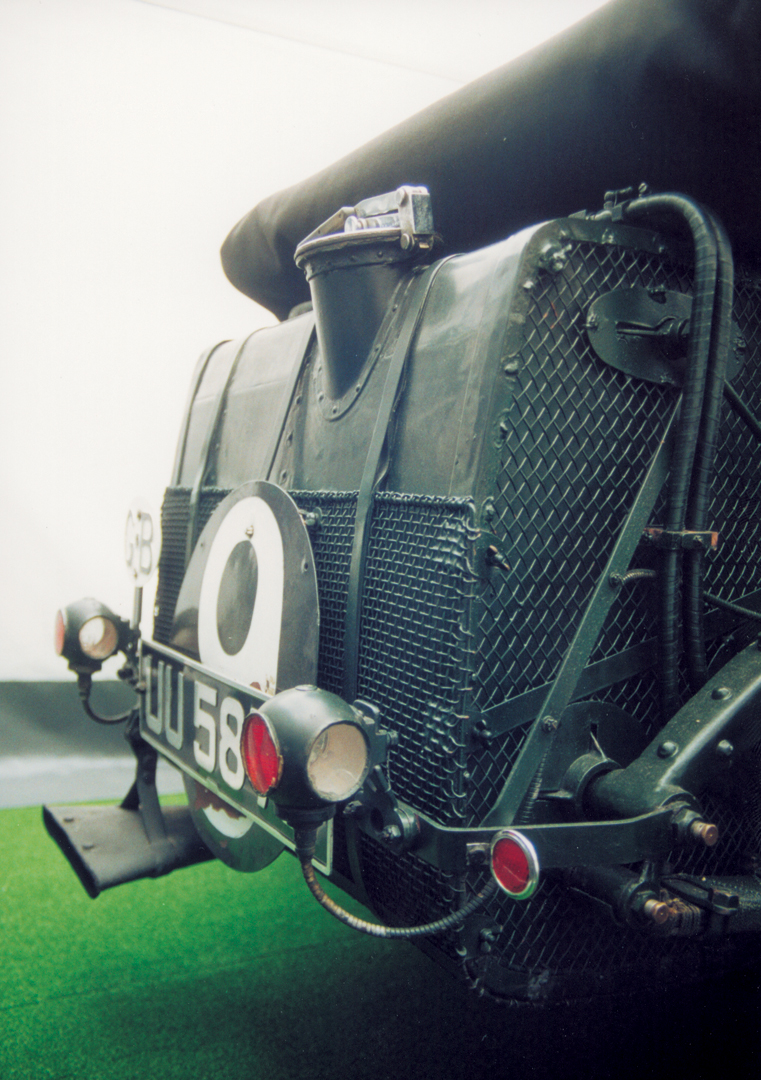

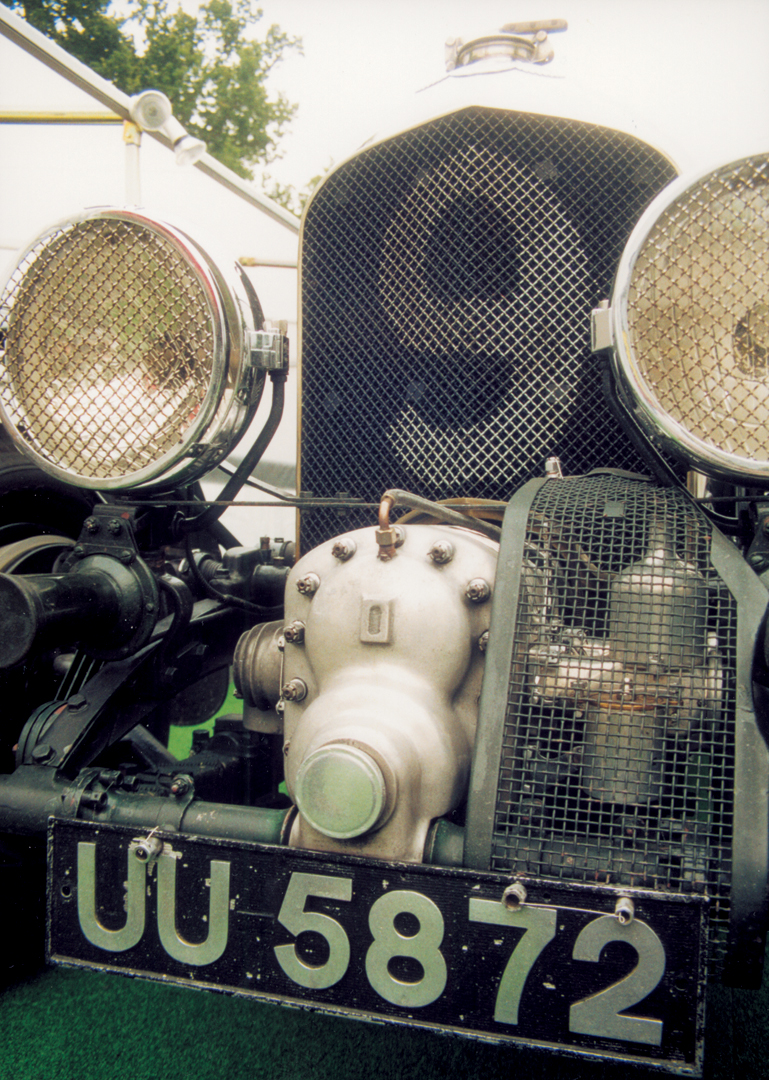

UU5872 – The Birkin Blower Bentley

Photo: Peter Collins

UU5872, recently acquired from a private collection by Bentley, was always known as “Number 2.” It was one of three supercharged Bentleys commissioned by Birkin in 1929. The “Blower” was basically a 4.5-liter Bentley with a Vanden Plas open tourer body, and it was fitted with a Villiers supercharger to boost power from 110 horsepower to nearly 200. While “WO’s” philosophy was to increase the engine size to gain power and retain reliability, Birkin’s argument was that the all-around performance of the blown car would be staggering… and it was.

A superb silver plaque on the car’s long bonnet proclaims this car’s achievements. As the “Number 2” car of the Birkin-Dorothy Paget Team, it first raced in the 1929 Irish Grand Prix in the hands of Bernard Rubin to eighth place at an average speed of 71.9 mph. Rubin drove it again in the Tourist Trophy of that same year. Then in 1930, Birkin drove it himself in the Brooklands Double Twelve-Hour race along with Jean Chassagne. For Le Mans in 1930, Birkin was again partnered by Chassagne, and the car carried number 9, as it does today, emblazoned across the huge radiator grill.

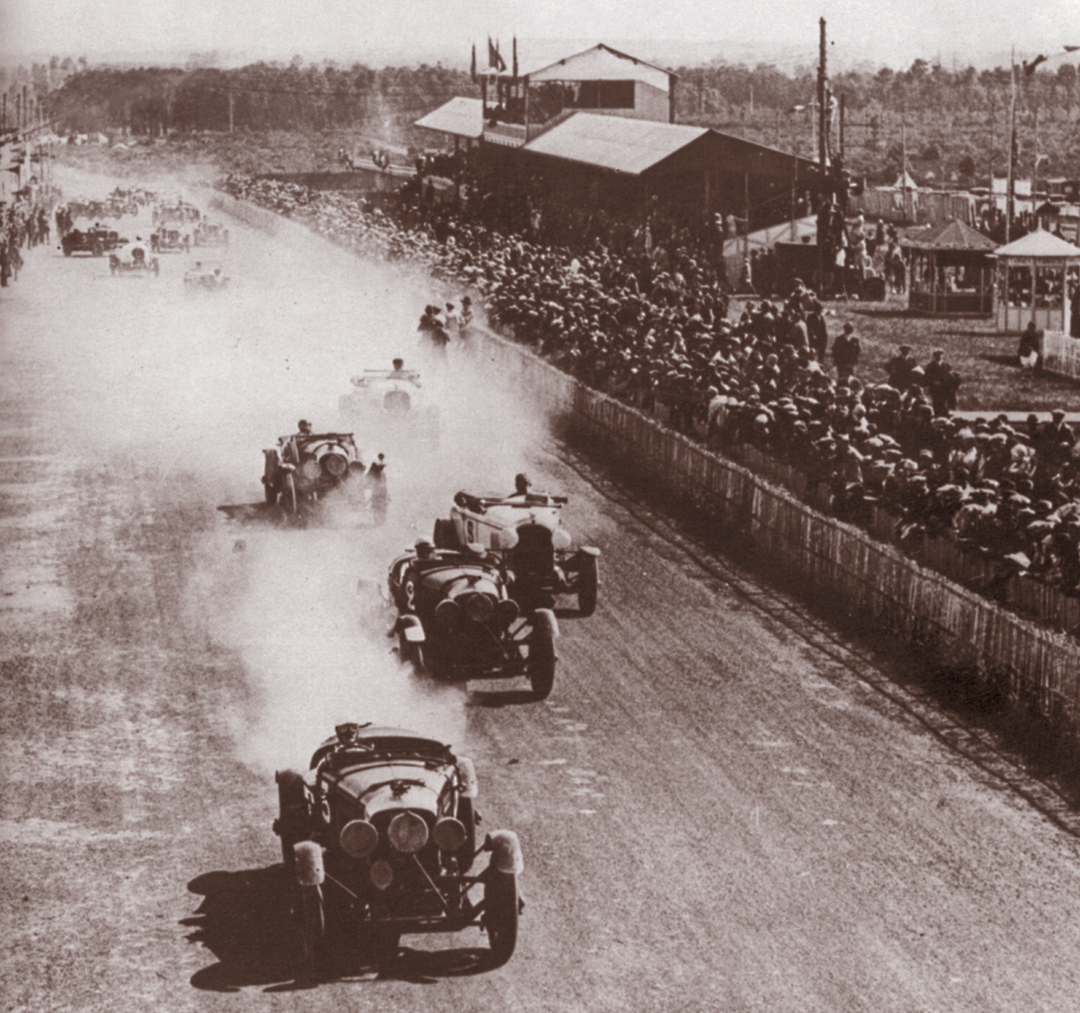

The 1930 24-Hours of Le Mans was the car’s most significant event, in spite of the fact that it retired. From the start, Birkin looked to have the measure of the Mercedes SSK entry. Birkin tucked in behind Rudi Carraciola for some laps before passing him on what is now the Mulsanne Straight, using the grass verge on the then narrow road to make his move. Carraciola then fought back but eventually suffered engine failure. Birkin and Chassagne looked as if they would prove the car to be fast and reliable, but with only four hours to go on Sunday it sadly expired. The Barnato/Kidston Speed Six won, while the sister car of Clement/Watney was second, with a third car having crashed. But it was Birkin, in establishing a lap record at 89.69 mph, who had destroyed the Mercedes opposition and in so doing gave birth to a legend. Unfortunately, the 1930 event marked the end of Bentley’s factory racing efforts.

Photo: Peter Collins

However, Birkin in UU5872, went on to a fourth place in the Irish Grand Prix and set a class lap record in thar year’s Tourist Trophy. Later, Benjy Benjafield and Eddie Hall drove UU5872 in the BRDC 500 Miles to second place at 112 mph at Brooklands. But, it wasn’t until 1959 when long-time owner S.E. Seers took a Flying Mile award at Antwerp in Belgium at 125.69 mph.

Birkin went on to win Le Mans in an Alfa Romeo, but subsequently died after sustaining an infection when he was burned at the 1933 Tripoli Grand Prix. Tragically, fellow Bentley Boy John Duff was killed in an air crash shortly afterwards. Duff’s death brought to a close a brief but glorious chapter in British motor racing history. In just four seasons, the epic Bentley legend was established, with the Bentley Boys lying at the heart of the legend and the Blower Bentley’s charismatic nature sustaining it for over 70 years.

Behind the wheel of a Blower

The first Bentley had been produced in 1919, a 3-liter, four-cylinder coupe, built at Cricklewood. Between this first “Red Label” 70 hp model and the following versions of the Speed and the Super Sport models, power increased and 100 mph became possible. The six-cylinder, 6.5-liter appeared in 1926, giving birth to the legendary “Speed Six.” 545 of these “fastest trucks in the world”, as Bugatti liked to call them, were built by 1930. Between the 3-liter and 6.5 models came a further 4-cylinder with a 4.4-liter engine and 665 of these were constructed, apart from 55 supercharged cars. Then along came the massive 8-liter model, of which 100 emerged from Cricklewood. A total of 3033 cars had appeared before the company closed down and Rolls Royce took over. Half of these cars are known to still exist.

As we have said, the idea of supercharging was anathema to “WO.” The unblown four-cylinder, 4-liter cars were always well loved. It was essentially a 3-liter with a bigger engine, and since it had the same 100 x 140 mm cylinder dimensions as the 6.5 models, many parts were interchangeable. In fact, many aspects of the cars of the time were very similar, endearing them to their owners but making it difficult for the ordinary person to tell them apart.

Sitting behind the wheel of Birkin’s unrestored car, it took me some time to assimilate the experience. This was the machine in which Birkin had so skillfully harassed the mighty Mercedes team, only feet from where I now sat, holding that great four-spoke steering wheel, absolutely necessary for managing this beast. Though you sit fairly far from the ground, the feeling isn’t one of being unduly exposed. I soon got to see what a brave man Birkin was, as the wheel was likely to heave you from the car coming out of a tight corner. Birkin had hunched behind this same small, oval-shaped windscreen as he sat behind Carraciola. His right hand would have slipped down to this same gear lever, just to the right of his knee, so he could balance the wheel and change gear just as I was doing now, the gearbox helping with its immense liquid smoothness. Birkin’s white scarf would have fluttered out behind him over the open rear compartment as he sailed down the straight past the Café de l’Hippodrome, the exhaust to the right bellowing away. The Dunlop race tires would squeal then as they did now exiting the Mulsanne corner, the 6.50 x 19 fronts and 7.00 x 19 rears producing good grip. He wouldn’t have had time to admire the wooden floor boards or the now worn but tidy green leather interior as I could.

In addition to the two glass screens, there is a large car-width metal fly screen which can be raised, but it didn’t appear to have seen much use in many, many years. It was, however, an integral part of the immense feel of this car.

The Bentley is surprisingly comfortable, and though some may have seen it as a truck, Birkin certainly didn’t, using the power of the engine to offset the car’s bulk and weight. Once I managed to move the adjustable(!) driver’s seat, I began to fully appreciate Tim Birkin’s view. I did manage to emulate his habit of not using the mirror and just turning to see what was going on behind. The expanse of space made that easy, as this is no cramped little cockpit.

I didn’t get the opportunity to repeat Birkin’s feat of breaking the lap record of 87 mph, which he did on his third lap in 1930, in pursuit of the big Mercedes. He had managed 125 mph down the straight but had lost a tire tread exiting a corner. However, amazingly it didn’t slow him for the lap, as he kept the engine on “full throttle” with the supercharger emitting a piercing drone. Even at two-and-a-half tons, the car could easily keep the Mercedes in sight and eventually at bay. If only Bentley could have seen its way to let me try a racing lap, I might have been able to fully test those big drum brakes! Multiple Le Mans winner Derek Bell, now racing consultant for Bentley, had two big emotional moments at Le Mans this year, one when they finished third with the EXP, the other when I stepped out of this great car and could share how special it was to have Bentley back in old and new form.

Buying and owning a Blower Bentley

The nature of these cars means they rarely come up for sale these days, though in the 1960s you could have found one quite cheaply. Bentley is reputed to have paid a very large amount to get this very historic car into its collection and that means it will be kept and preserved.

The large and thriving Bentley Drivers Club provides support and help, as well as inspiration to potential owners, and many Bentleys race regularly in historic events. The rigours of ownership are closely related to which model you find and what condition it is in, of course, but many long-time owners who use their cars regularly say that regular servicing is all that is needed to keep a prewar Bentley going. Now there is a nice 3-liter car of 1934 vintage coming up for auction in London at Coys on July 30. There’s your chance.

Photo: Bentley Motors

Specifications

Chassis: Pressed steel ladder frame

Body: Aluminium and canvas by Vanden Plas

Wheelbase: 2984 mm

Length: 4876 mm

Weight: 4256 lbs

Suspension: Front: Beam axle front with semi-elliptical springs. Rear: Semi-floating live axle with semi-elliptical springs.

Steering: Unassisted worm and wheel.

Engine: Inline, 4-cylinder, 4 valves/cylinder, SOHC.

Capacity: 4486 cc

Bore: 100 mm

Stroke: 140 mm

Ignition: Twin ML Magnetos

Induction: Villier supecharger with Zenith or SU carburetors.

Gearbox: Bentley A-type 4-speed

Clutch: Cone type

Horsepower: 240 @ 4200 rpm

Power per liter: 53.5

Maximum speed: 130 mph

Brakes: Cast iron drums

Wheels: Rudge-Whitworth wire wheels

Resources

Lyndon, B.

Combat – A Motor Racing History

Windmill Press, 1933

Surrey, UK

Moity, C.

The Le Mans 24-Hour Race

Edita, Geneva, 1979

ISBN 0 85059 188 0

Stein, R.

The Greatest Cars

Ridge Press, London, 1979

ISBN 600 32186X

Very special thanks to John Crawford, Deborah Risby and Lisa Palmer at Bentley Motors, and Derek Bell.

Bloodlines: Bentley R420

The design brief must have been simple. Take Bentley’s luxurious Continental, imbue it with a 6.75-liter, turbocharged, all-aluminum V-8 (that belts out 420 horsepower and a stunning 645 ft/lbs of torque!), add 18” wheels, stainless steel grills, dual tail pipes and Voilá! Undoubtedly, the world’s fastest luxury car.

When it comes to performance, the R420 holds its own in this department as well. The R420’s turbo V-8 and 4-speed automatic are capable of launching this 5,500 lb car from 0-60 in 5.8 seconds with a top speed of 167 mph. But perhaps more surprising than these numbers is the car’s feel out on the road.

If you’re interested in owning a truly fast and unique luxury car – and can stomach the price tag – the Bentley R420 is definitely a car in a class of its own.

Reviewed by Casey Annis