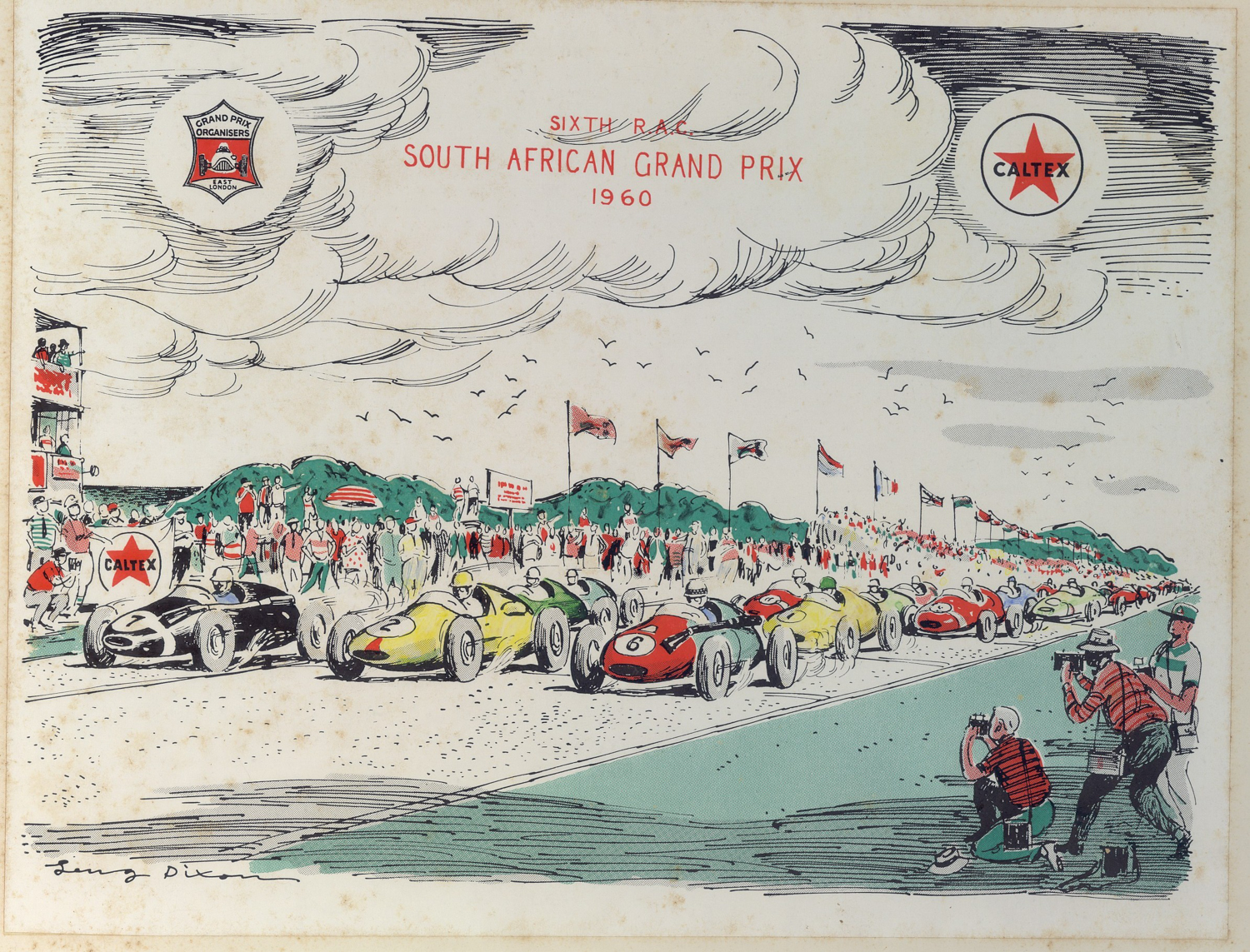

In late December 1959, Bill Jennings packed his tools, spares and suitcase into the passenger seat of his self-assembled GSM Dart sports car and drove from his home in Cape Town to East London – a trip of over 600 miles in the days before highways. Jennings then took part in the Sixth International South African Grand Prix, finished the 150-mile Formula Libre race in 11th place of 24 starters after averaging nearly 75 miles an hour and then added a pint of oil to the sump and drove the 600 miles back home to be at work on Monday!

“I had got some leave between Christmas and New Year. The race was on New Year’s Day of 1960 – a Friday, so that suited me fine because I could drive home on the Sunday and be back in time when the workshop opened on Monday morning.” Recalled Bill.

The Grand Prix was the first major international race in South Africa since 1939 and hugely significant on the local map. It was won by Paul Frére in the Ecurie Nationale Belge Cooper T51 Climax, at a race average of 85 miles per hour, after Stirling Moss’s Cooper-Borgward, which had led until the closing laps, lost power due to a cracked fuel pipe and had to be nursed home to second place.

Derek “Bill” Jennings’ association with things mechanical and his fascination for speed began when, as a boy of eleven, he began tinkering with an old Indian motorcycle on the family farm near the diamond fields of Kimberley. Then, after attending the 1935 Kimberley ‘100’—where he was to witness the daring feats of Doug van Riet in an Indianapolis Studebaker, ill-suited to the largely unsealed “track”—his interest in racing himself was kindled.

“After watching these chaps I knew what I wanted to do.” So he decided to train to be a motor mechanic and at the age of 15 left home to work in faraway Cape Town – “a big city.” But then WWII intervened.

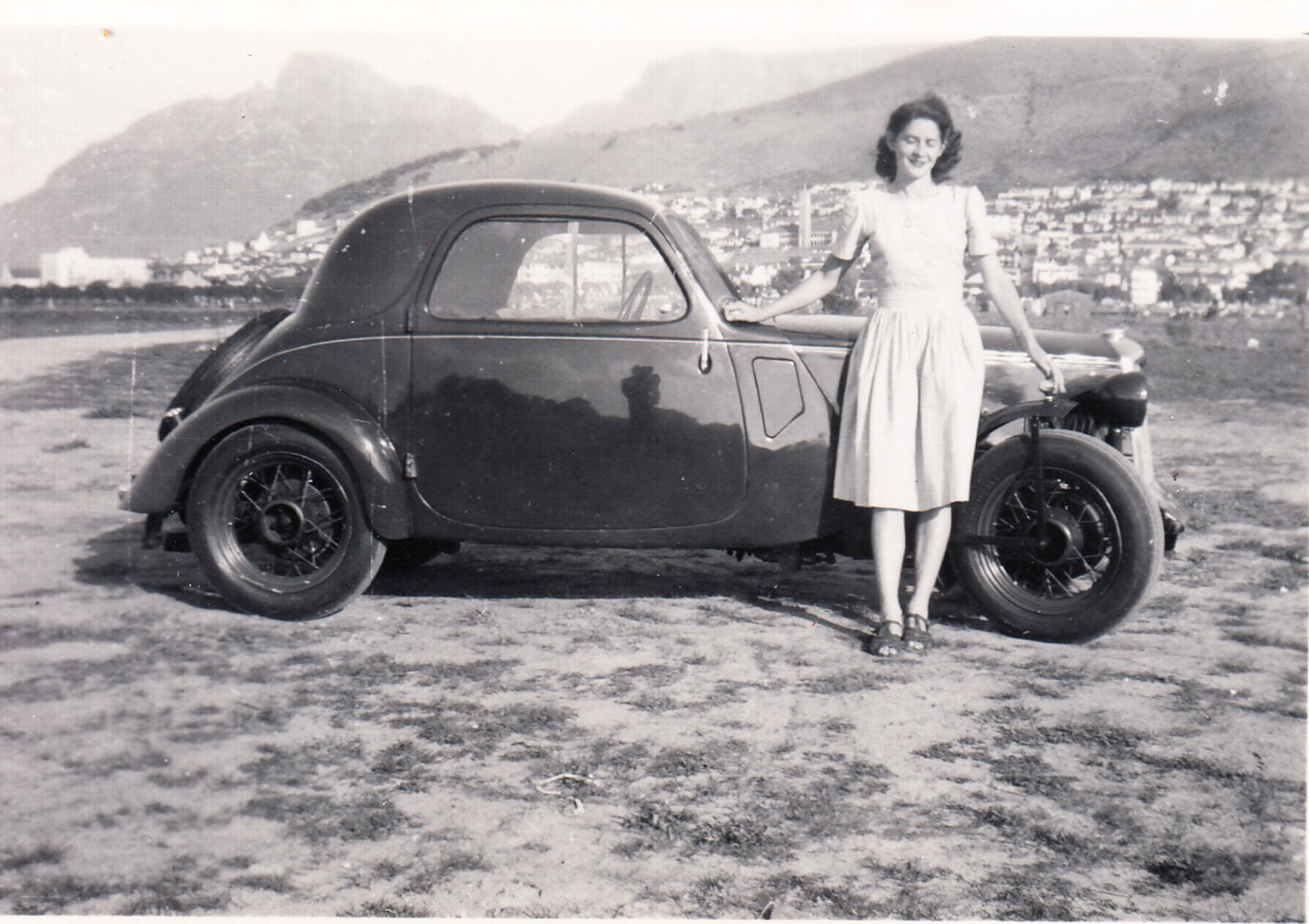

Honeymoon car

In 1947, after being demobbed from the South African tank corps where he had served in Italy, he chose to get married but he did not own a car so he decided to quickly build one in order to take his new wife, Maureen, on their honeymoon!

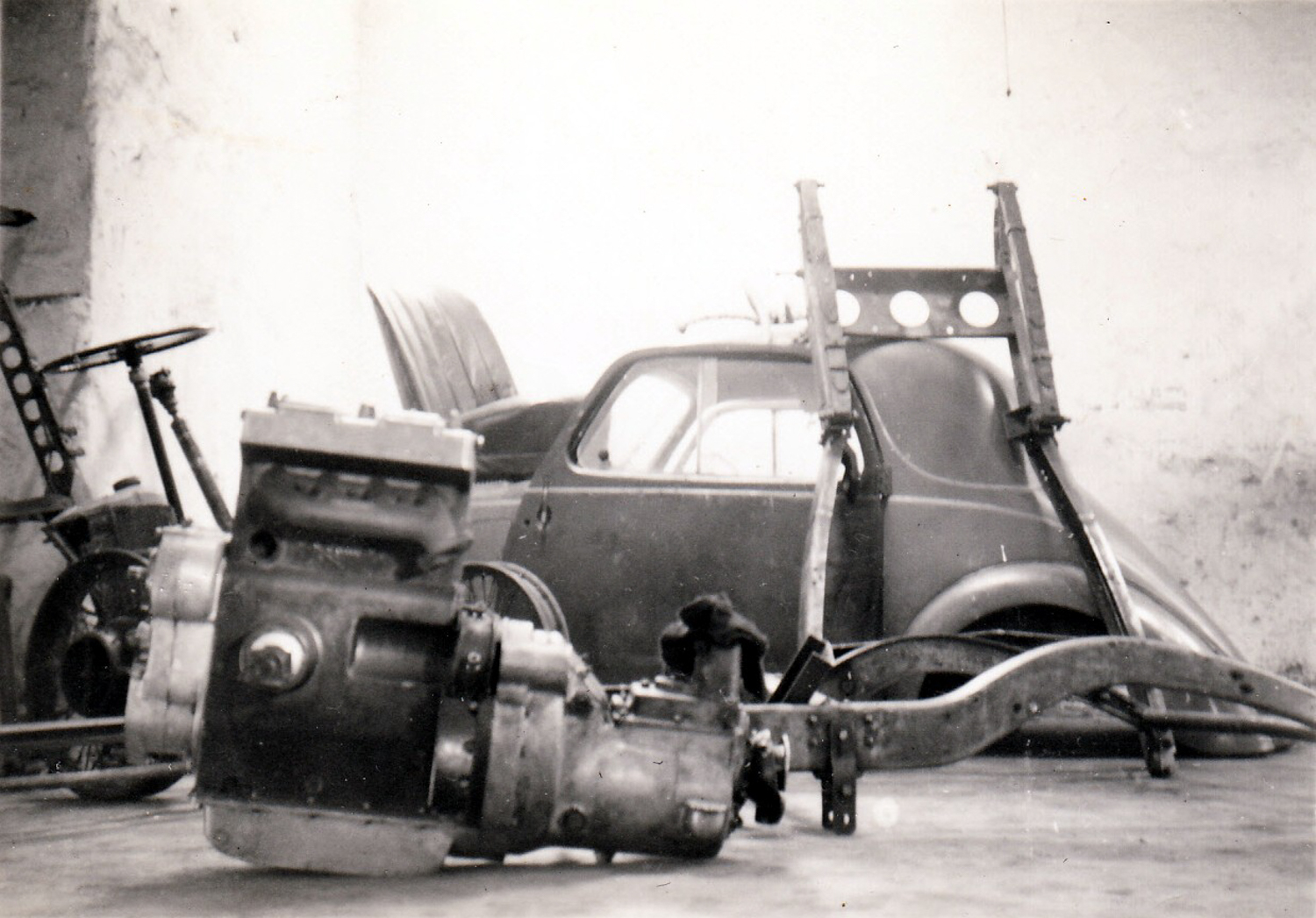

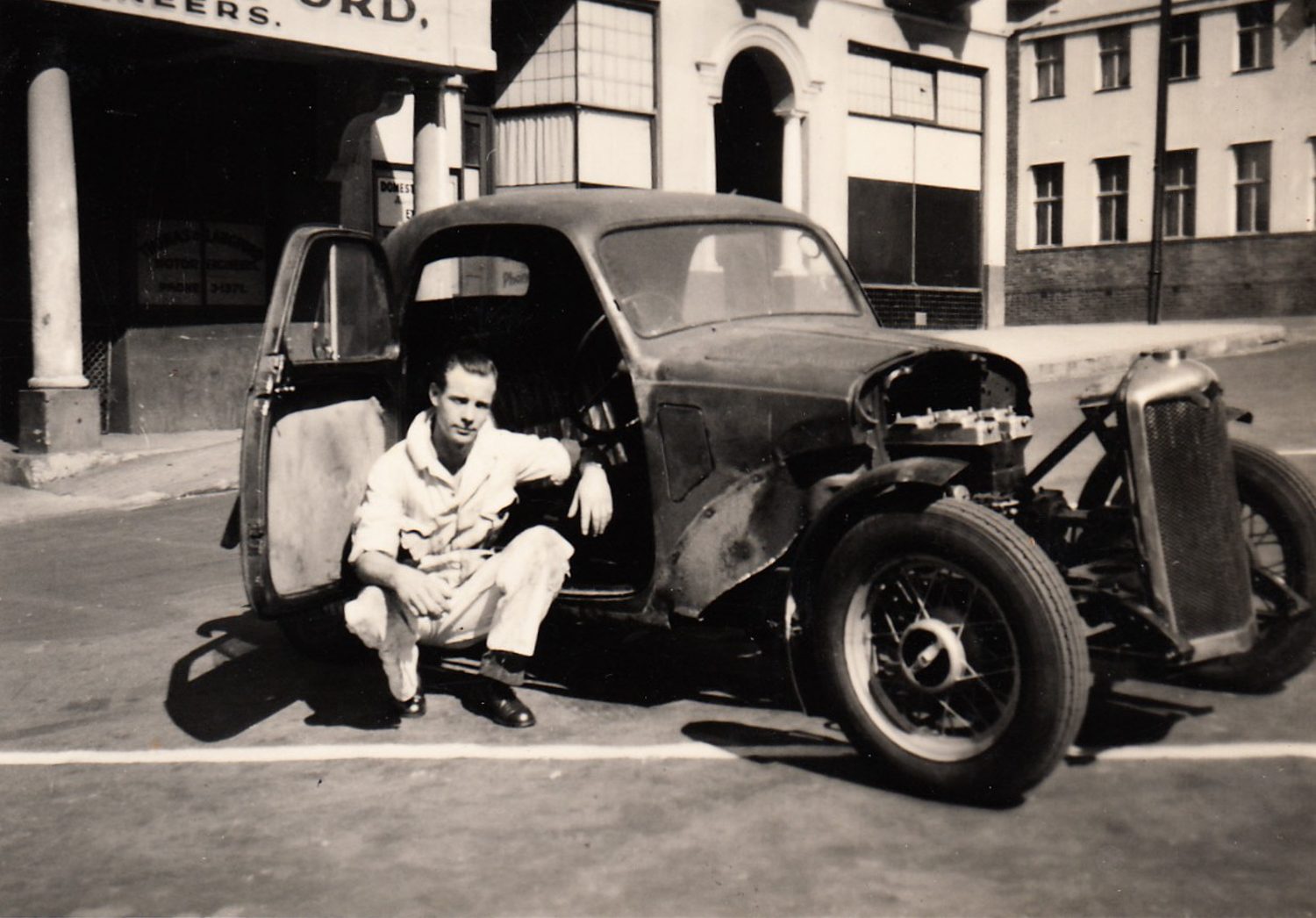

A visit to the local scrapyard resulted in Bill buying the rear end of a damaged Fiat Cub, the front end of a Riley with engine and gearbox, a Wolseley chassis and other ‘bits and pieces’.

The finished product turned out to be an attractively styled and speedy machine, which gave Bill the idea of using it as a dual-purpose competition car.

Junkyards

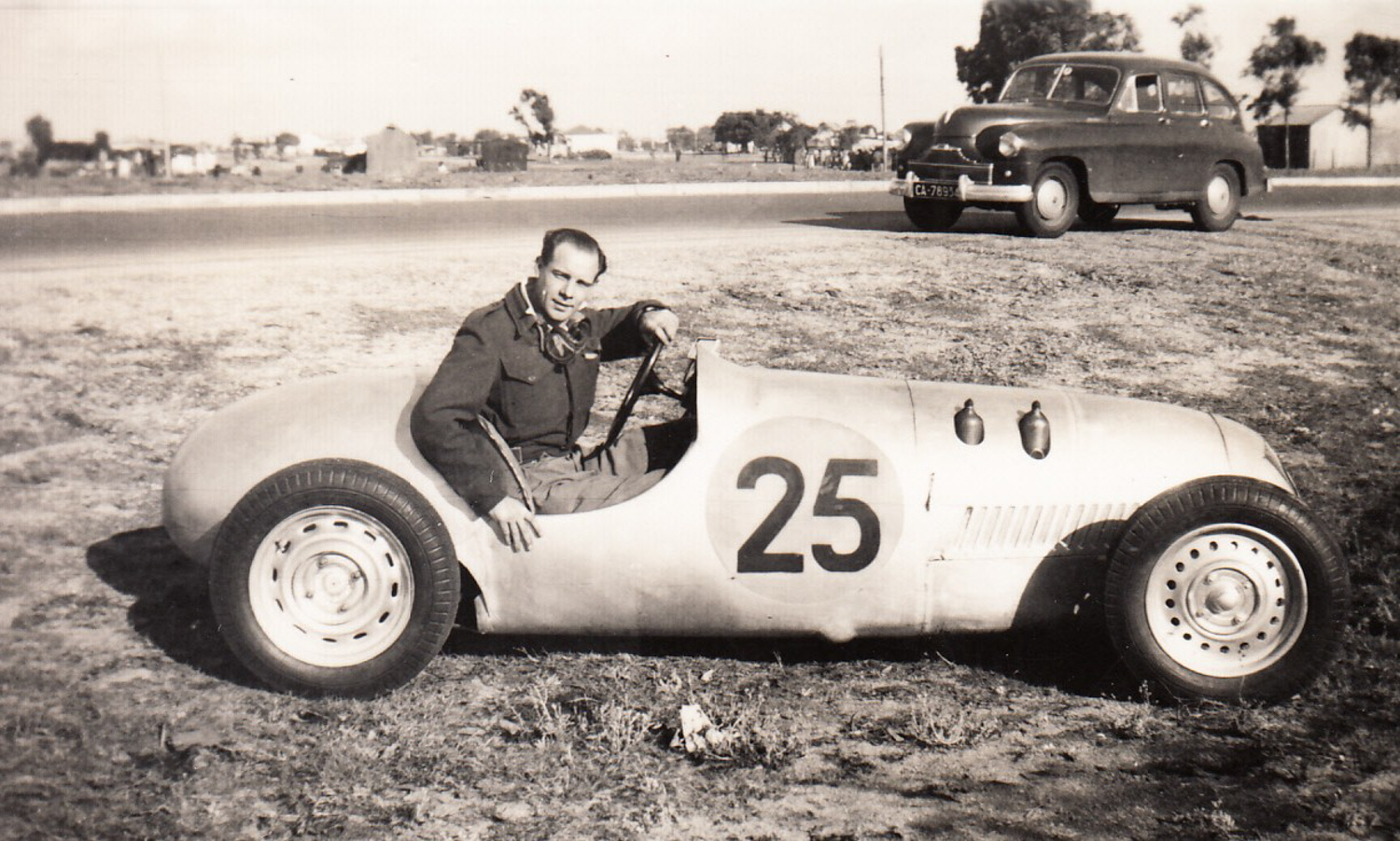

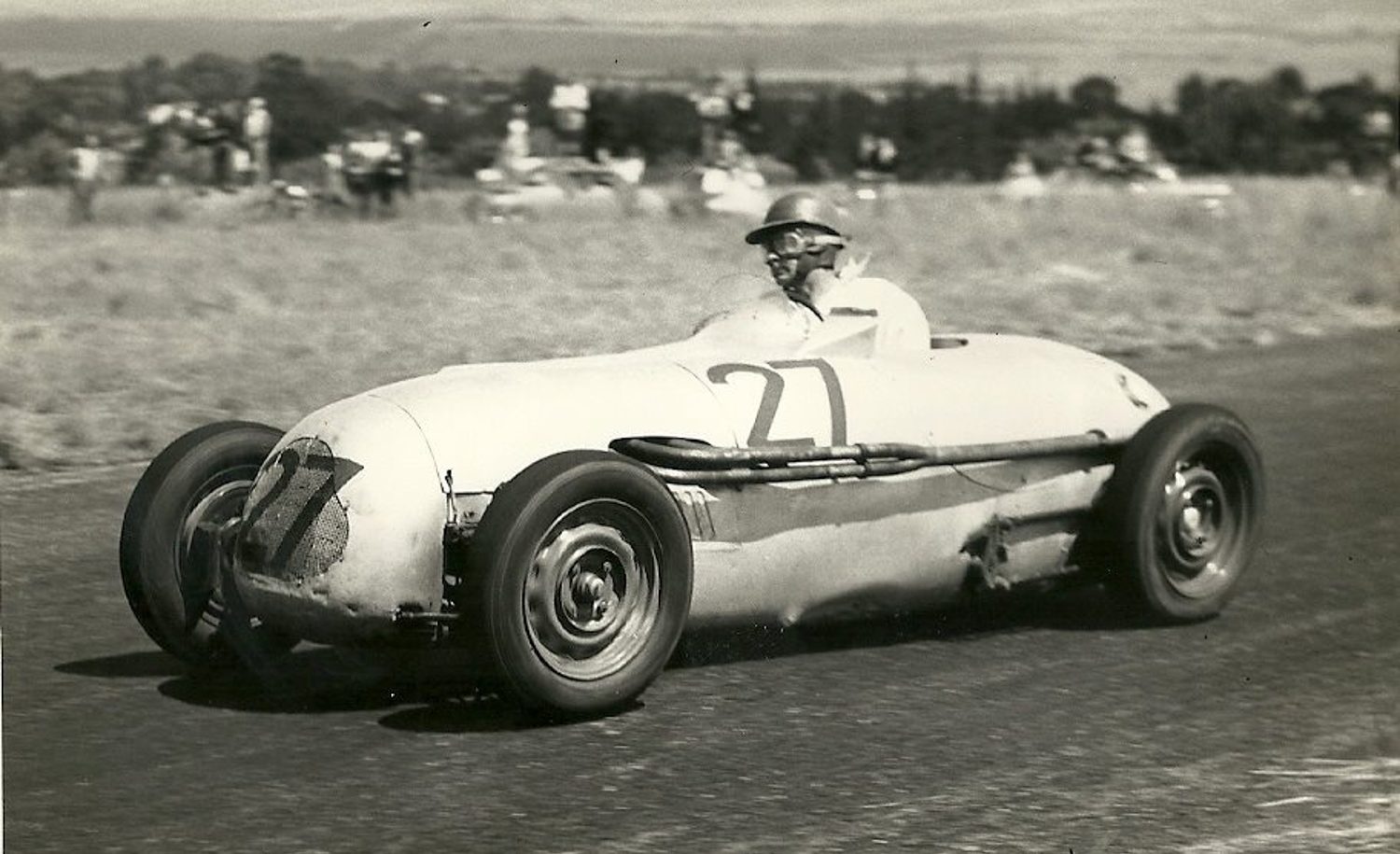

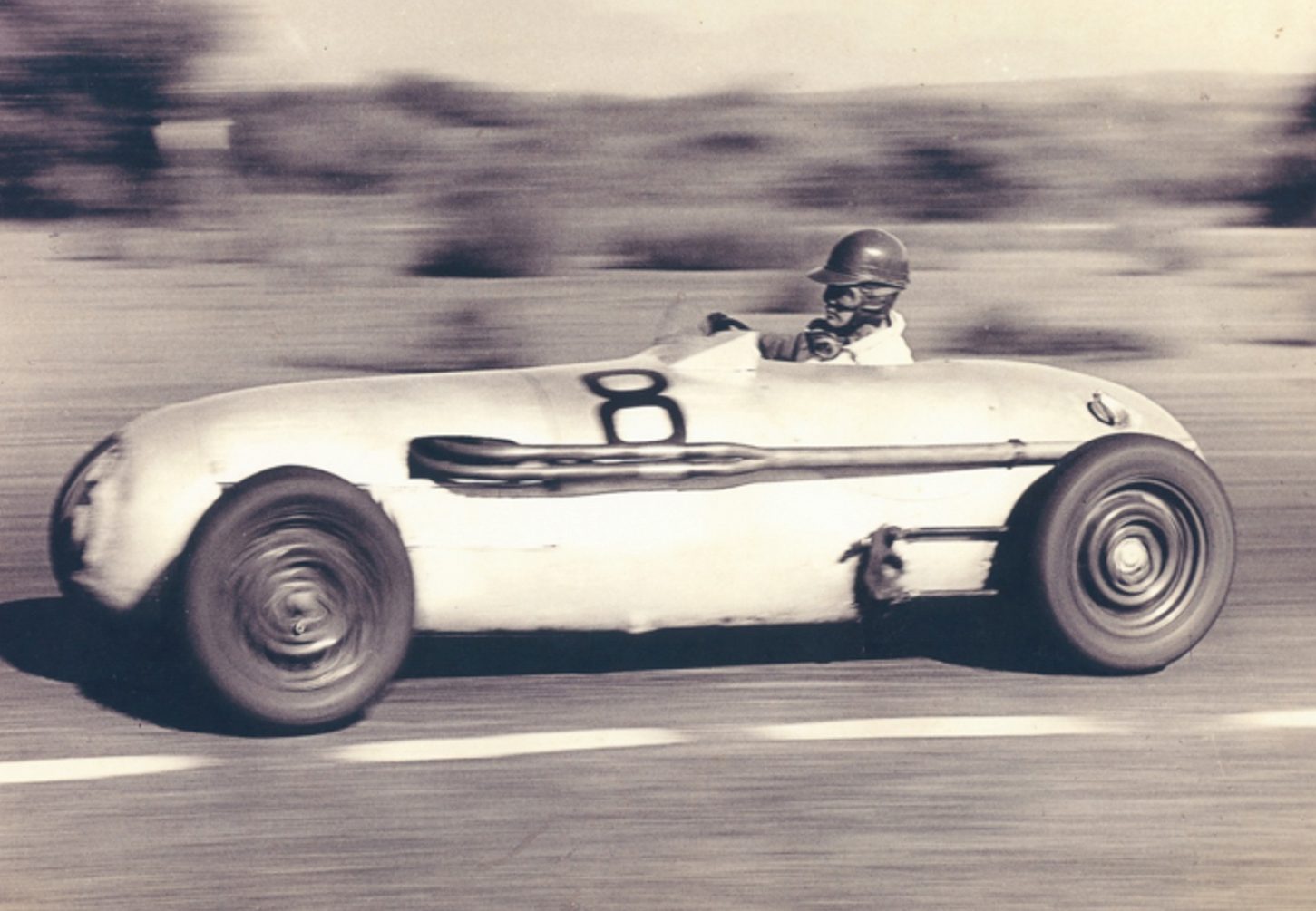

As motor sport became popular in South Africa after WWII, Bill made more visits to the junkyards and constructed a mid-engined racecar mounting his Riley engine transversely in a modified Fiat chassis using a Harley-Davidson drivetrain.

According to Jennings, “The first competition car was built in 1948, this being a 1100-cc, rear-engine Riley to be used mostly for sprints and hillclimbs, as not knowing how I would fare in motorsport I had no real aspirations. The engine being about 1933 vintage was not very strong, although it could be made to develop quite a bit of power (4-Amal carbs etc.) resulting in a third place at East London in 1951, as well as being twice hillclimb champion in the Cape.”

Racing enthusiasts traveled vast distances at the time to compete in events around the country and tows of 1 000 miles, much of it on untarred roads, were common.

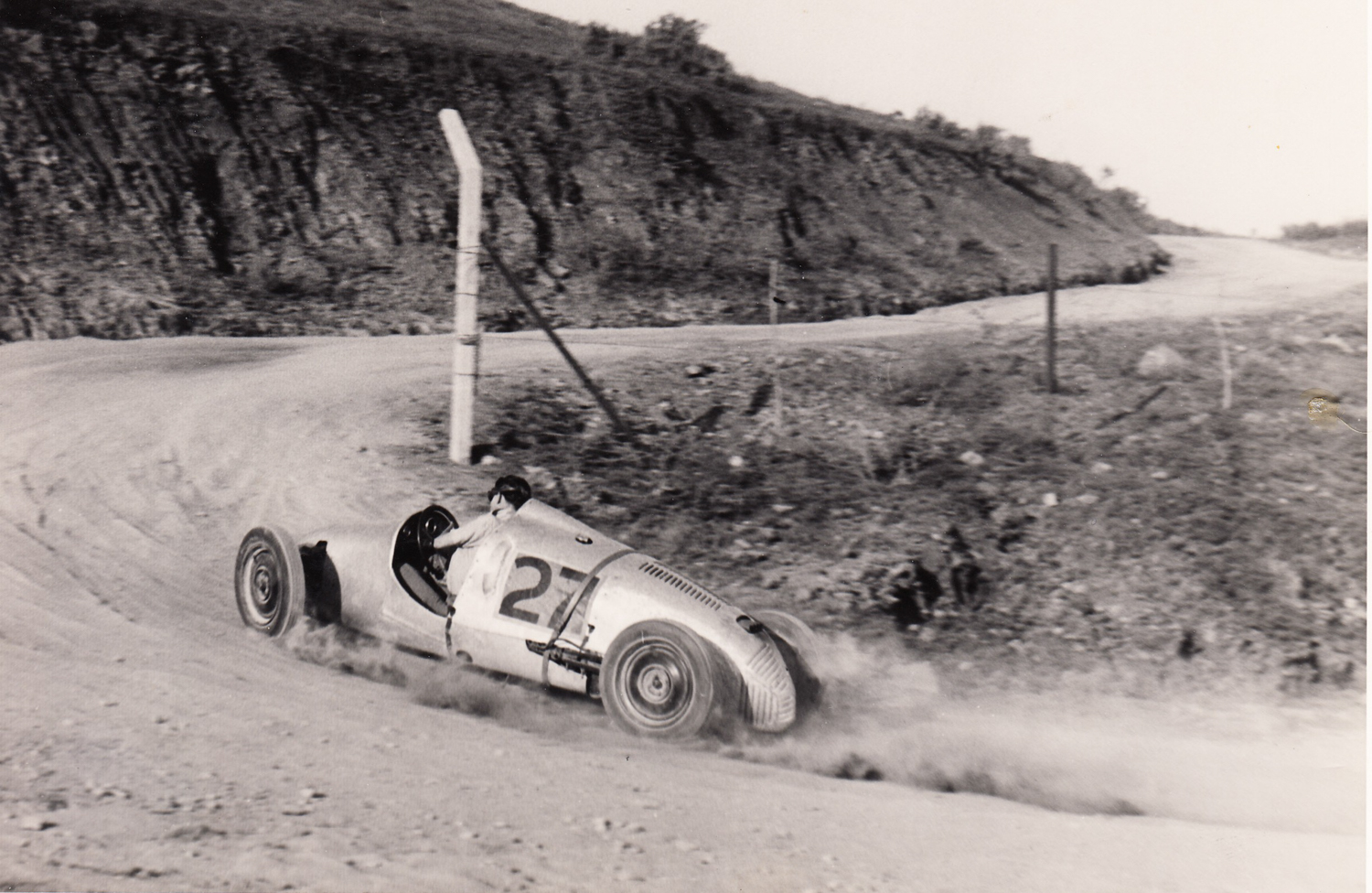

This racing special incorporated some of the early 500-cc Cooper ideas and styling and was fast and very competitive in hillclimbs and sprints, but unreliable over the longer distances due to the susceptibility of the crankshaft to break under stress due to its two main bearing design.

Encouraged by his successes so far, but aware that to be competitive in the championship road races that were being staged around the country he needed to construct something more suitable and cast his eye about for “the makings.”

The Riley Special

During the 1937 pre-war series of South African “summer” international races, the local Riley agents had imported the Riley TT Sprite AVC16 but the car had a huge accident during the opening event, the South African Grand Prix, and was extensively damaged.

Fellow Cape Town driver, Edgar Hoal acquired the remains some time later and raced it during the late 1940s and early 1950s. In order to make the car more competitive Edgar soon fitted a 2½ liter engine and AVC 16 raced very successfully in this guise and became one of the most successful cars on the local grids.

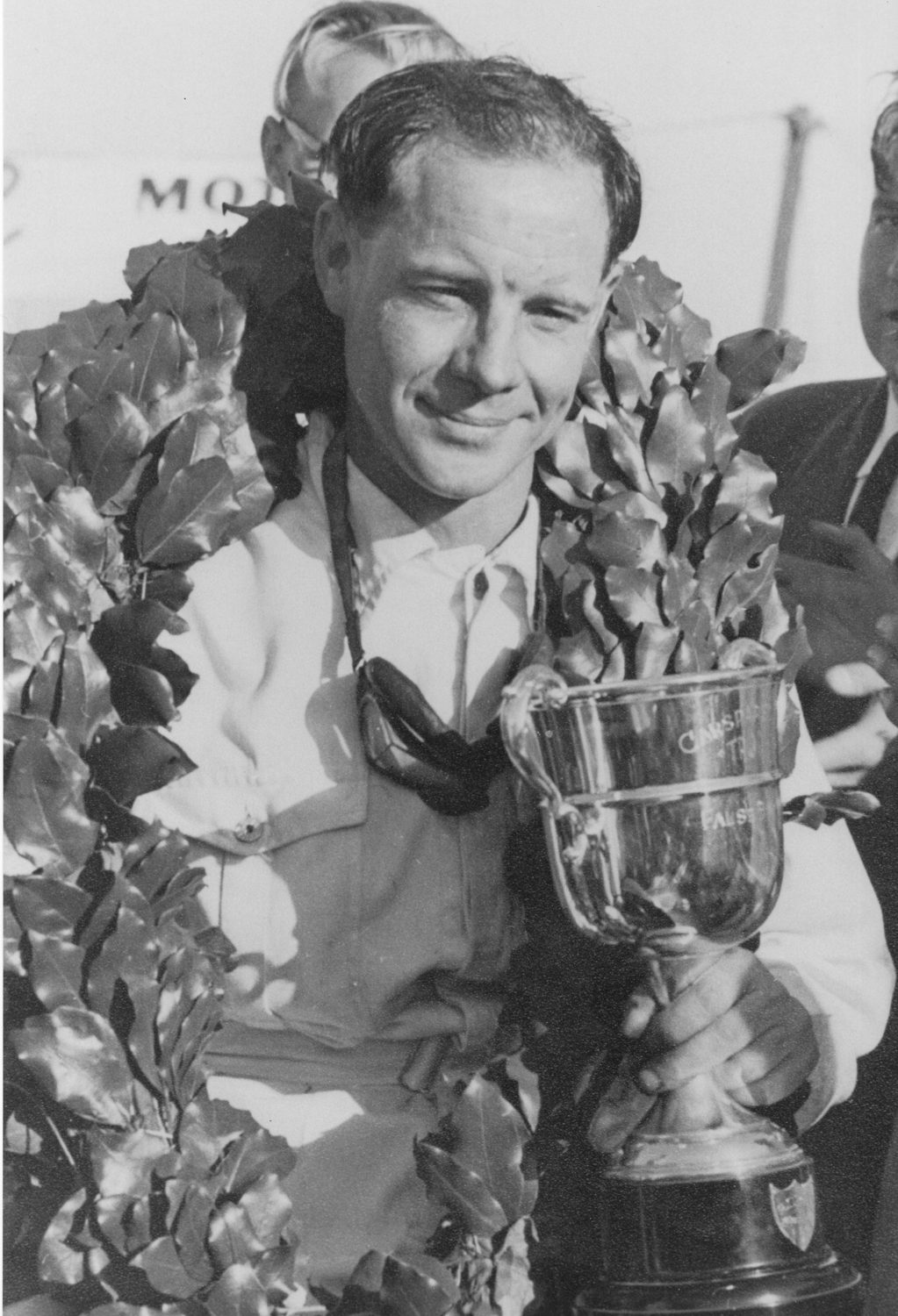

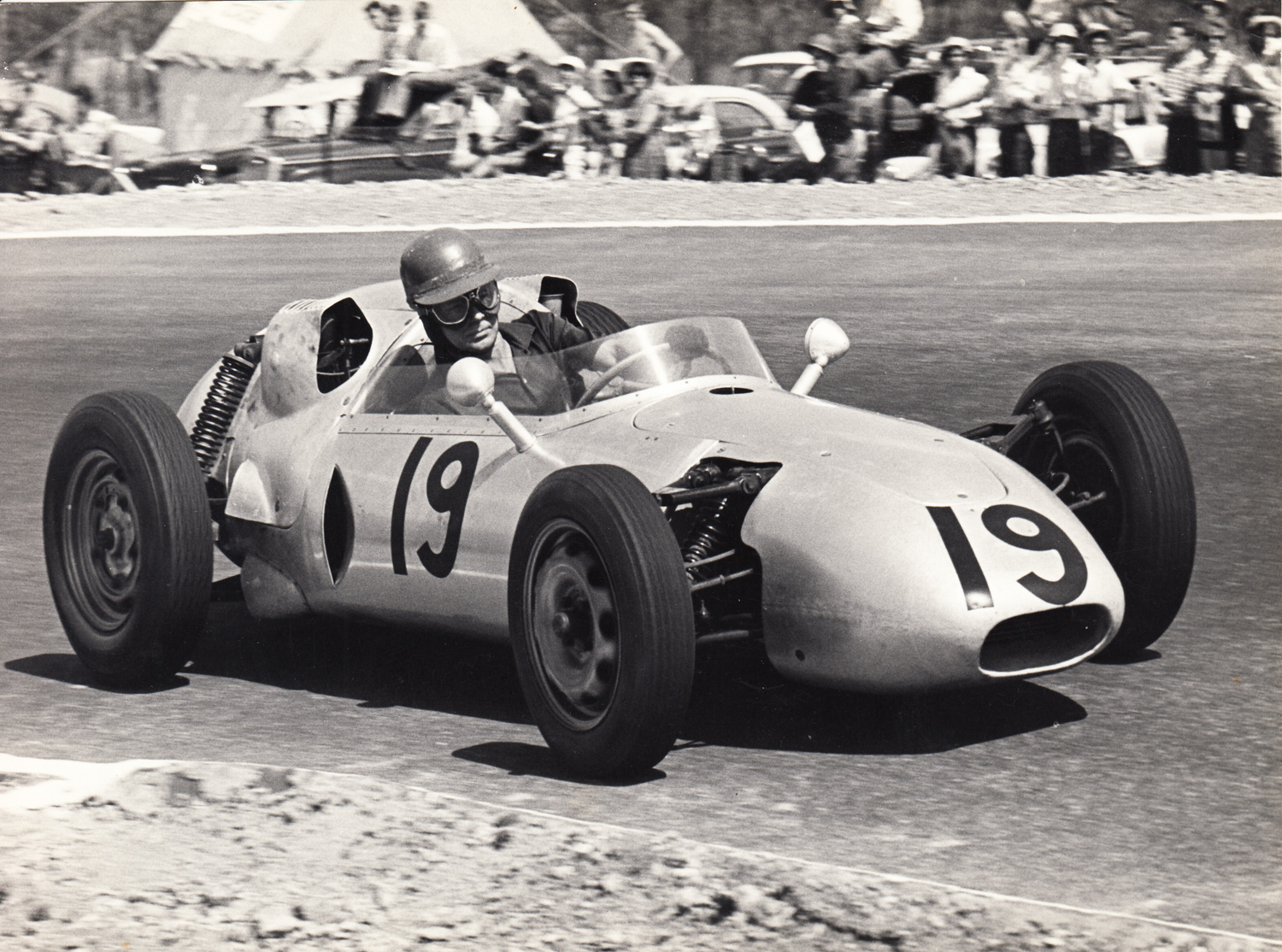

And what a racing car this turned out to be. It ranks as the most successful “special” built in South Africa. Jennings was to use the cigar-shaped Riley Special to win the South African Driver’s Championship in 1954, 1956 and 1957. He was second in 1955.

Bill chose the Riley engine because he believed in its reliability and potential if developed. “It was designed to run long distances and had a very low compression ratio of some 7:1. But by fitting bigger big end bolts, increasing the compression ratio to 9.5:1 and various tweaks to the cylinder head and exhaust, fitting four Amal carburetors and altering the camshaft profiles I was able to rev it to 6 000 rpm,” he said.

“I became rather well known at the scrapyards around Cape Town,” recalled the resourceful constructor. He fashioned a traditional ladder-type chassis from four carefully selected propshafts cut and then welded end to end and installed the Riley engine up front using a close ratio sports-type gearbox with straight-cut gears driving the rear wheels through an Austin A40 differential and an Austin A90 crown-wheel-and-pinion.

Front springing was by torsion bars A-arms and telescopic shocks from a 1948 Dodge and at the rear were quarter elliptics, trailing arms and a Panhard rod.

More scouring of the scrapyards found brakes and wheels and uprights from a 1950 Fiat and Bill welded on locating spots and machined them into fins to cool the drums. A rack and pinion steering rack from a Morris Minor was also used.

“I built the Riley as a narrow two-seater, so that it could be used as a sports car, in case it turned out to be an unsuccessful single-seater. This also enabled me to sit much lower to one side of the propshaft, instead of astride.”

The offset driving position to the right of the propshaft allowed the driver to sit low down and out of the airstream.

To clothe the racer, a lightweight hand-formed aluminum body was attached. To save weight (and the cost of paint) it was not painted. The polished aluminum looked stunning though.

Jennings did not have access to sophisticated tools or machinery and painstakingly modified the camshaft and cylinder head, doing the grinding by hand.

By the time he sold the car he estimated that it was producing some 135 bhp compared to the 75 bhp it had made when he acquired the motor.

As a “man on the bench” Bill was not always able to get time off work, nor afford the costs, to travel to all the championship rounds in the vast country and so carefully selected the events he could participate in. As such, in 16 ‘major’ events during this four year period, he registered only one ‘did not finish’ while winning on scratch nine times and scoring four second place finishes! The Riley Special, often severely handicapped, also achieved six wins on handicap.

It was not as if the competition was sub-standard either. The Riley Special had to contend with a hoard of well-constructed MG Specials, a 2.5-liter Riley, imported Cooper-Bristols, imported 500-cc Cooper-Nortons, big capacity pre-war Maseratis and V8 American powered specials that lined up among the large entries of the day.

The Riley Special was not only rapid by local standards. During the 1957 summer season Ronnie Moore and Ray Thackwell brought their 1100-cc single,-cam Coventry Climax-engined Cooper T43s to do a racing tour of South Africa and Rhodesia together with Lord Michael Louth (D-Type Jaguar). The combination of the Riley Special and Bill Jennings was more than a match for them. In the 1957 “1820 Settlers” Trophy, Jennings beat the Coopers in a straight fight and in the van Riebeeck Trophy, Bill was second on scratch to Moore but won on handicap.

Moore, who was a world speedway champion, and an experienced and capable racecar driver recalled :

“The man to watch was the reigning South African champion, Bill Jennings. He was driving what everyone liked to call a 1934 Riley – though I have never seen anything less like a car of this name or vintage. The whole thing had been rebuilt and redesigned by Jennings, right down to the last nut and bolt. Had there been a concours d’elegance, he would have won it hands down. It was one of the most beautifully finished racing-cars I have seen. And it performed as well as it looked.”

Motor racing on an amateur basis required long trips of over 1000 miles from major center to major center and Bill decided to hang up his helmet in October 1957 and sold the Riley Special to a young Rhodesian driver named John Love, who would launch his serious racing career with it after having cut his teeth on motorcycles and 500-cc Coopers.

Angolan Grand Prix

Love raced the Riley Special during 1958 and had a most successful time with the silver cigar and was competitive in both Rhodesia and South Africa. He won the Rand Autumn Trophy outright and had three second place finishes in the major races. By this time, the opposition was becoming more modern and the Porsche 550 Spyder of Ian Fraser Jones was beginning to dominate.

Another amazing performance of the ancient Riley was in the 1958 Angolan Grand Prix on the streets of Luanda, where Love finished third in a race of some 200 miles at an average of over 74 mph. The race was won by the Jaguar D-Type of Jimmy de Villiers but among the field of high powered sports racers the Riley amazed everyone with its pace and durability. The second placed car, a modern Ferrari Testa Rossa of more than twice the Riley’s capacity, driven by Count de Changy averaged 75.7 mph, after making a pit stop – but Love also had to stop for petrol.

The Dart

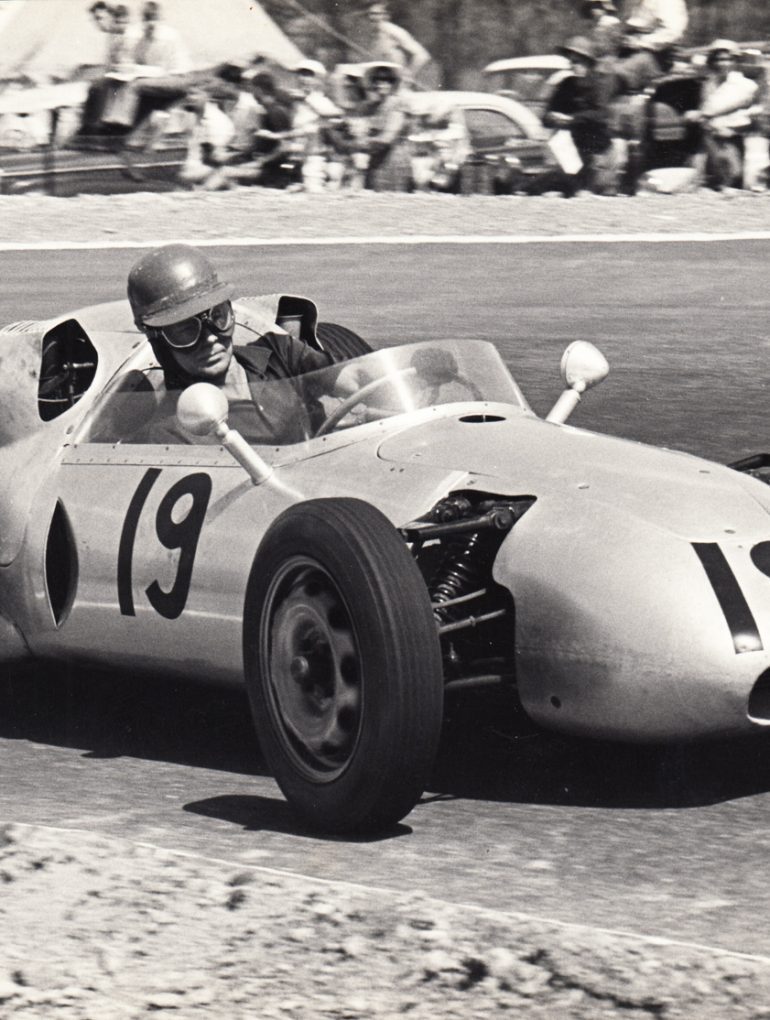

The lure of the tracks was too much and so Jennings made a comeback at the age of 36. He decided to build a sports racer and in 1959 he set about fitting a 1500-cc, four-cam Porsche 356 Carrera motor into a lightweight front-engined GSM Dart sports car bodyshell. (The South African designed GSM Dart was also manufactured in Britain as the GSM Delta.) Jennings helped with the construction of his special lightweight bodyshell.

“The dry-sumped motor was, of course, in front coupled to a VW gearbox casing to facilitate mounting to the chassis and that also acted as an engine oil-container. The gearbox-differential mounted at the rear was coupled to the motor by a light propshaft, running at engine speed through the VW casing and at rear a carrier bearing attached to the Porsche bell housing. The c-w-p was not ‘reversed’ as in my later single-seater.”

Bill’s “trial and error” idea of the mounting of the engine “up front” separated from its transaxle at the rear was what Porsche did much later with the 924, 944 and 928!

Bill was never happy with the Dart. He liked cars that handled well. “The back end was all Porsche so it stuck like a leech and the car understeered terribly. Even Bob van Niekerk and Willie Meissner, designers of the Dart and acknowledged experts at the time, did not know what to do in order to eliminate the chronic understeer.”

During its run at the 1960 South African Grand Prix it understeered so badly through the flat out Potter’s Pass that it wore a flat spot on the left front Michelin X tire and hampered his progress. Nonetheless, he was the third sports car home behind the Porsche 550 Spyder of Ian Fraser Jones and John Love (D-Type Jaguar) and outpaced a Ferrari, a Maserati-Chevy, Tojeiros and a Lotus 11, amongst others. The Dart was timed at over 120 mph over the straight sections.

The Jennings Porsche

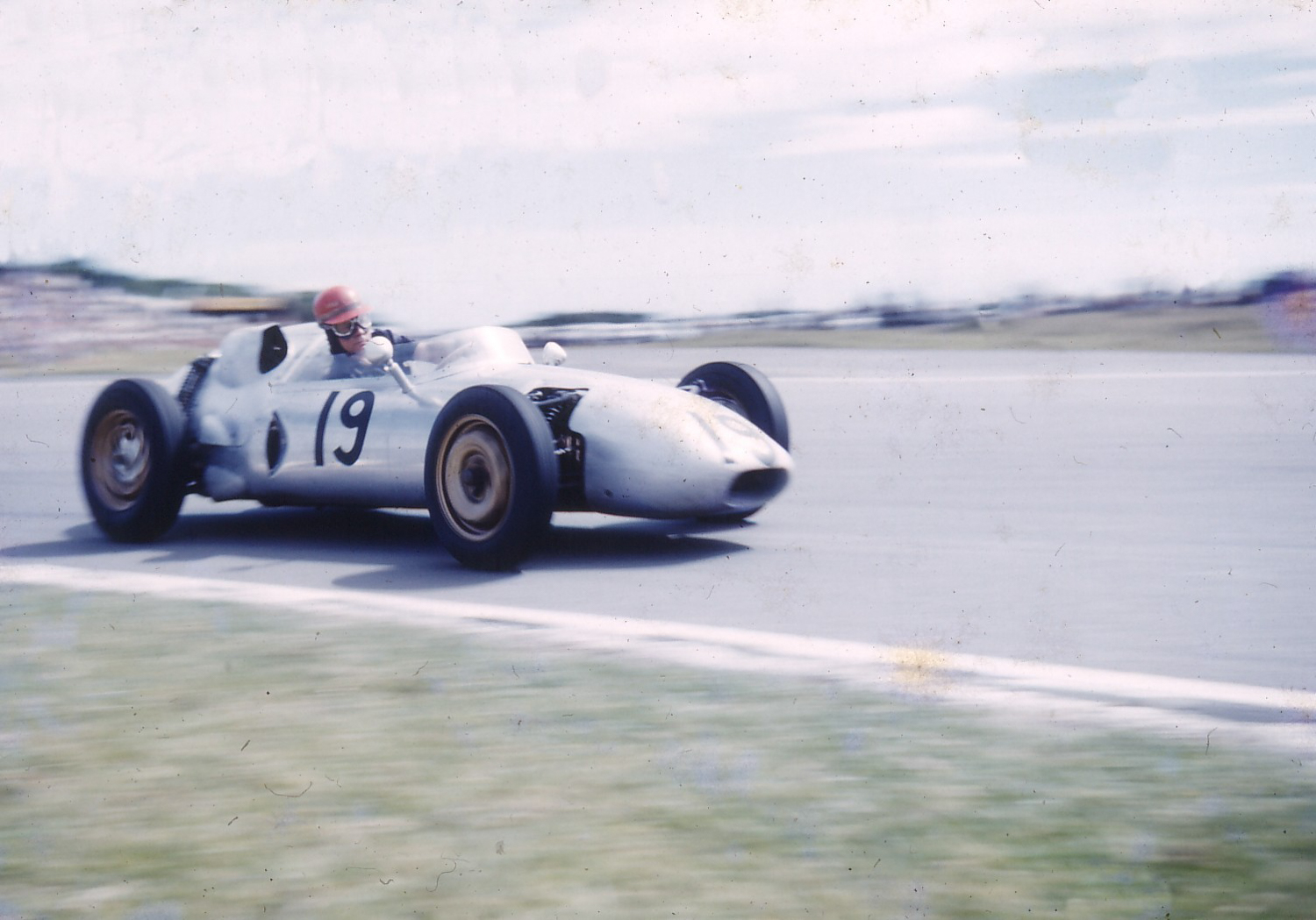

The African motor racing scene was becoming more professional in the early 1960s and as more imported rear-engined marques such as Cooper and Lotus were appearing on the grids Bill, now 40, decided to build something more competitive – a rear-engined single-seater, using the Porsche engine from the Dart.

Working at night and on weekends, he spent three months constructing a tubular chassis. The car was clothed in a silver aluminum body crafted by a skilled ‘artist of the English wheel’ named Charles Hatton – along the lines of the Porsche 718 but not copied from it. It was far slimmer and drew the admiration of Hushcke von Hanstein and Stirling Moss, when they brought the factory Porsche 718s to Africa for the December 1960 Sunshine series.

“ Baron von Hanstein indicated that he would provide me with a full race Porsche engine and gearbox but nothing ever came of it.”

The Jennings-Porsche was not a success. “The engine was ahead of the wheels so the c-w-p was reversed. I had terrible trouble with the gearbox overheating and always had to pamper it. Although reliable it was horribly down on power and even the fitting of RSK pistons and cams did not help much.” Bill sold the car after a disappointing time with it and hung up his helmet.

Jennings was a versatile driver and besides racing the cars that he built himself he competed in a number of events driving cars ranging from a Ferrari Vignale, a factory entered Austin-Healey, various Fords and a tiny Fiat 850 Zagato.

A Riley man through and through, Bill summed it up, “I believe that had the Riley engine and box been fitted to the Porsche-Dart and Jennings-Porsche single-seater their performances could well have been better – wishful thinking perhaps! I must admit though that both cars were raced for approximately only 15 to 18 months each, hardly enough time to get them sorted and performing at their best, bearing in mind that most of us had to earn our bread and racing money during the week.”