1934 Team Talbot 105s

When the conversation turns to the great prewar race and rally teams, the big names—Bentley, Maserati, Alfa Romeo—tend to dominate the list that is produced. Certain marques managed to get a great deal of attention at the time and have hogged the memory of most prewar enthusiasts. That leaves a lot of important players and stories out of the equation. However, we have had the very good fortune to develop a longer-term relationship with some of the lesser-known, but very significant cars of the 1930s.

Early in 2005, a new event was announced for the UK, the Tour Britannia, bringing back the style and memory of the 1970s Tour of Britain. Modeled on the classic Tour Auto in France, it had a challenging combination of road stages, races, rally special stages and hill climbs. Whereas the original ’70s event was for current cars, the new Tour is for classics, both pre- and postwar. With the help of event organizers Fred Gallagher and Alec Poole, I was fortunate enough to find myself co-driving with Gareth Burnett in one of John Ruston’s Team Talbot cars, the 1934 Talbot 105, registered BGH 21. While we tackled the competition division of the Tour, Ruston himself won the regularity section with co-driver Jeremy Haylock, in a sister team car. (They even repeated the feat in 2006.) We won the class and would have won the prestigious handicap award but for a driveshaft failure at the last stage, on the last day! The performance of the Talbot was stunning, and this co-driver saw 120 mph on the clock at one point…though I dare not reveal where!

John Ruston’s cars, including several prewar Talbots, are prepared and raced by Gareth Burnett, one of the UK’s quickest historic drivers, and his GBRace Engineering preparation firm specializes in important classic racing machines. The Talbots have featured at Classic Le Mans, Spa and Silverstone, and BGH 21, 22 and 23 all returned to Classic Le Mans this year where Burnett finished 2nd in the prewar group, behind a Grand Prix 4.5-liter Talbot-Lago. I got the chance to try BGH 23, famously known throughout its prewar career as “Big Talbot,” as it was being prepared for yet another Le Mans race.

Talbot cars

The history of Talbot is, to put it mildly, complex. I have heard people say Talbot is English. I have heard people say Talbot is French. Tal-bott vs. Tal-bow!

In the last year of the 19th century, 1899, Adolphe Clement moved from manufacturing bicycles to automobiles, and the Clement was a reasonable car. The British were slightly behind the French in early car building, and so a new company was formed to provide a vehicle based on the Clement. The main investor was the Earl of Shrewsbury and Talbot, and in 1902, Clement-Talbot was created. Though there was a factory in London, the first cars delivered to British customers were French-built. The London-built cars then found a good market, and enjoyed success at Brooklands in its early years. Around the same period, Darracq was building cars in France and Sunbeam was doing the same in the U.K. After WW1, Darracq took over Clement-Talbot and produced the Talbot-Darracq car, and nine months later amalgamated with Sunbeam to form STD Motors Ltd.—Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq. This company produced good road and racing cars from 1919 until about 1927, but world economic conditions saw STD shrink until it died altogether in 1935. The individual makes within the company ranged from small saloons to essentially Grand Prix racecars, some built in Britain and some in France. Cars raced as Talbots, Talbot-Darracqs, or Darracqs were immensely successful in racing from 1921 until 1926. This period gave birth to the title “the Invincible Talbots” for the racing cars of the time.

The STD Company was not doing well in 1927 and sales dropped severely. With one exception, which we will come back to, failure was on the horizon. In 1935, STD sold Clement-Talbot to Rootes Securities, which later became the Rootes Group. Soon thereafter, Rootes also bought Sunbeam, adding to Humber, Hillman and Commer, which they already owned. STD was wound up and the final piece of the conglomerate, Automobiles Talbot of Paris, was left to carry on, on its own. In 1938, Rootes pulled two of their acquisitions together as Sunbeam-Talbot. Rally success came to the Sunbeam-Talbot 90 in the 1950s and in 1955, the Talbot name was dropped to avoid confusion with Tony Lago’s French Talbot-Lago. Lago had refloated and developed the French Talbot Company and produced a very quick range of GP and sports cars. The Talbot name died in 1960 when Tony Lago also expired, though the Talbot brand had been bought by Simca in 1958. In the 1960s, Chrysler turned Simca into Chrysler-France and the Rootes Group into Chrysler UK, and this became the basis of Chrysler-Europe.

In 1978, the PSA Peugeot-Citroen combine bought Chrysler-Europe and renamed all the Chrysler-Europe products Talbots…thus Talbot was reborn. The last Rootes Group car, the Chrysler (Hillman) Avenger remained in production, as a Talbot until 1981. The awful Talbot Tagora was made from 1981 to 1983. Peugeot gradually replaced all the various Talbot models, and the final Talbot was a van in 1992. Talbot also had a brief foray into F1 in the early ’80s with Matra and Ligier.

The Roesch Talbots

I mentioned an exception when discussing the declining fortunes of the STD firm. Georges Roesch was a brilliant German-Swiss who had been chief engineer at Talbot before the Darracq takeover. In 1925, he moved from France to London to design a completely new Talbot, the 14/45 and then the 18/70 and 18/75 models. These were production road cars and were very successful at a time when Sunbeam and Darracq were suffering. Roesch was pressed into building a team of racing Talbot 75s for Arthur Fox, whose company, Fox and Nicholls, would build the racing bodies for the cars. In lean times, Roesch’s 6-cylinder OHV engines were so good that the Fox and Nicholls backing allowed them to go racing seriously.

All Roesch Talbots were 6-cylinder cars, later cars being fitted with the Wilson pre-selector gearbox which Roesch specially redesigned for his use. The Roesch Talbots developed from the 1,666-cc-engined 14/45 through the Scout which was lengthened to become the 65, which was enlarged to become the 75. This was then, in turn, “souped up” to make the 90. These cars had 2,276-cc engines and formed the basis of Fox and Nicholls’ first efforts in 1930. The 1930 cars, PL 2, PL 3 and PL 4—as well as the 1931 and 1932 cars—had 4-speed, manual, crash gearboxes and a normal clutch except that its spring arrangement was the forerunner of today’s diaphram clutch.

Talbot’s racing effort was, on reflection, pretty amazing. The development work was done on a shoestring as the main parent company, STD, was in trouble. The cars became known as the Team Talbot cars during the first half of the 1930s, though they were private, production-based machines. The Fox and Nicholls team 90s, painted white, made their debut at the Brooklands Double Twelve race. It was an inauspicious occasion as PL 3 and PL 4 crashed on the first of the two days and the team was withdrawn.

The three cars then went to the Le Mans 24 Hours with PL 2 as the practice car. Lewis and Eaton were in PL 3 and were an amazing 3rd overall and 1st in class on handicap. Hindmarsh and Rose Richards were 4th overall, 2nd in class and 3rd on handicap. It was a stunning performance for the highly underfinanced team of Brits. At the Irish Grand Prix, PL 2 won the class and was 6th overall, with PL 3 and PL 4 8th and 9th overall and 2nd and 3rd in class. At the Tourist Trophy, they were again 1–2–3 in their class, a performance they nearly repeated at the Brooklands 500, where a single special was the class winner and PL 4 retired. This single-seater was used to set a number of British and International speed records in 1930, as well.

The 105 arrives

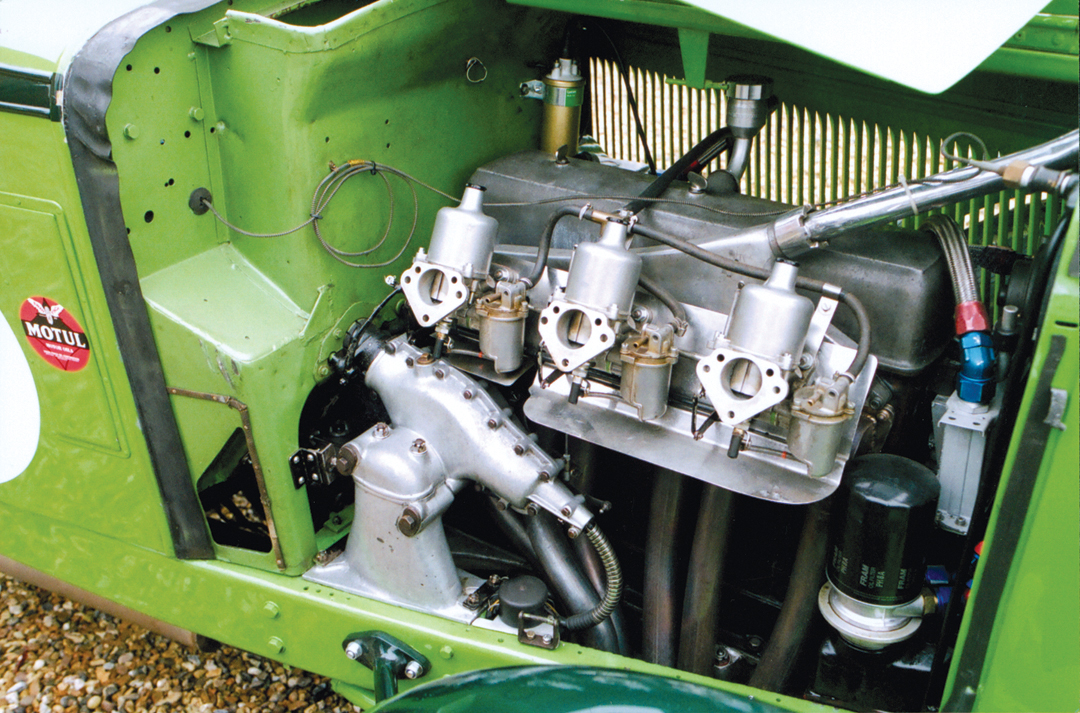

For 1931, Georges Roesch increased the engine capacity to 2,968-cc by giving the block an increased bore and stroke of 75 mm x 112 mm. The cylinder head was re-worked with staggered bathtub combustion chambers to allow bigger valves and porting, and Roesch’s famous lightweight valve gear was further improved with ultra-light ball pivot rockers and knitting needle-like push rods. The engine produced 105 bhp @ 4,500 rpm in touring form, and thus came the model name…105. The racecars ran on benzol and had a 10.2 to 1 compression ratio, producing up to 140 bhp. While Roesch attempted to stick with the single downdraft Zenith carburetor, there were experiments with both twin and triple SUs.

There were essentially four 105s run by Fox and Nicholls for 1931, registered GO 51, GO 52, GO 53 and GO 54, while the 90-based single-seater made occasional appearances, as well. The team had a much better time at the 1931 Brooklands Double Twelve. GO 54 was the practice car, and GO 51, with Lewis and Hindmarsh were 2nd overall and 2nd in class, while Rose Richards and John Cobb took the outright win and the class, with Saunders Davies/Craig 5th overall and 3rd in class. This performance had a positive effect on production car sales and kept Talbot going as other STD fortunes continued to decline. As Lewis/Hindmarsh retired while 2nd at Le Mans in GO 51, Rose Richards and Saunders Davies were 3rd, winning the class. Lewis had managed 6th in the Irish Grand Prix, again winning the class. GO 51 and GO 52 were 4th and 5th at the Tourist Trophy, with GO 53 and GO 54 4th and 3rd at the Brooklands 500. The single-seater was 2nd in this race while GO 52 retired while 3rd. GO 54 had also won a Glacier Cup in the 1931 Alpine Trial, while the single-seater did a number of races at Brooklands. It was a 105-based single-seater, which had appeared at the Brooklands 500. In 1931, the team cars had been painted an attractive apple green, and that remained the team colors, and singles out the cars even today.

A very similar team tackled the 1932 season, with GO 53 crashing at 900 miles in the Mille Miglia while 4th, with GO 54 as the practice car. The Brooklands Double Twelve was replaced by the Brooklands 1000, where GO 53 and GO 52 were 1st and 3rd overall. A car known as GO 51a had been built to replace the original GO 51, which was the basis of the 105 single-seater. This car finished 2nd in the “1000” with Lewis and Cobb. GO 53 and GO 54 went to Le Mans, and this time GO 54 was 3rd overall and 53 was the practice car. Four cars were at the Tourist Trophy, getting 3rd and 4th overall. At the Brooklands 500, the single-seater won outright, GO 52 was 2nd, 51a and 53 retired and GO 54 was the practice car. Also during 1932, Warwick Wright Ltd. sponsored three 105s in the Alpine Trial, PL 7361, 7362, 7363 for Lewis, Rose Richards and Norman Garrad and they won the Alpine Cup Team Prize with zero penalties. The “GO” cars continued to race in private hands, and as this is being written, GO 54 is coming up for auction by H & H Classic Auctions, with an estimate between $340,000 to $400,000. Interesting, considering these cars changed hands after 1936 for about £300!

Big Talbot

The 1932 competition season was far less successful than expected for the Talbots. The Clement-Talbot firm had decided to cease racing, and that meant the end for Arthur Fox and his team with Talbots. With the new pre-selector gearbox on schedule for 1933, the next season should have been very good for Fox and Nicholls. But the ‘GO’ cars were fettled and put up for sale. In 1933, the MG Magnette took the mantle from Talbot as the best British racing car. There was no Talbot works support for competition that year, and it was clear by the end of the year and the beginning of 1934 that the company was in serious trouble. There was an enormous amount of maneuvering behind the scenes, and this would end in STD going into receivership and Talbot would be sold off to Rootes to redeem an outstanding bank loan.

This was all going at a time when Roesch was at the peak of his career and design ability. He had been working on an enlarged engine of 3.3-liters. The block remained the same, bore and stroke was increased to 80 x 112-mm and power went up to 164 bhp@4,800 in racing trim with a compression ratio of 11.4 to 1. This was one of the first engines to use Tony Vandervell’s bearings.

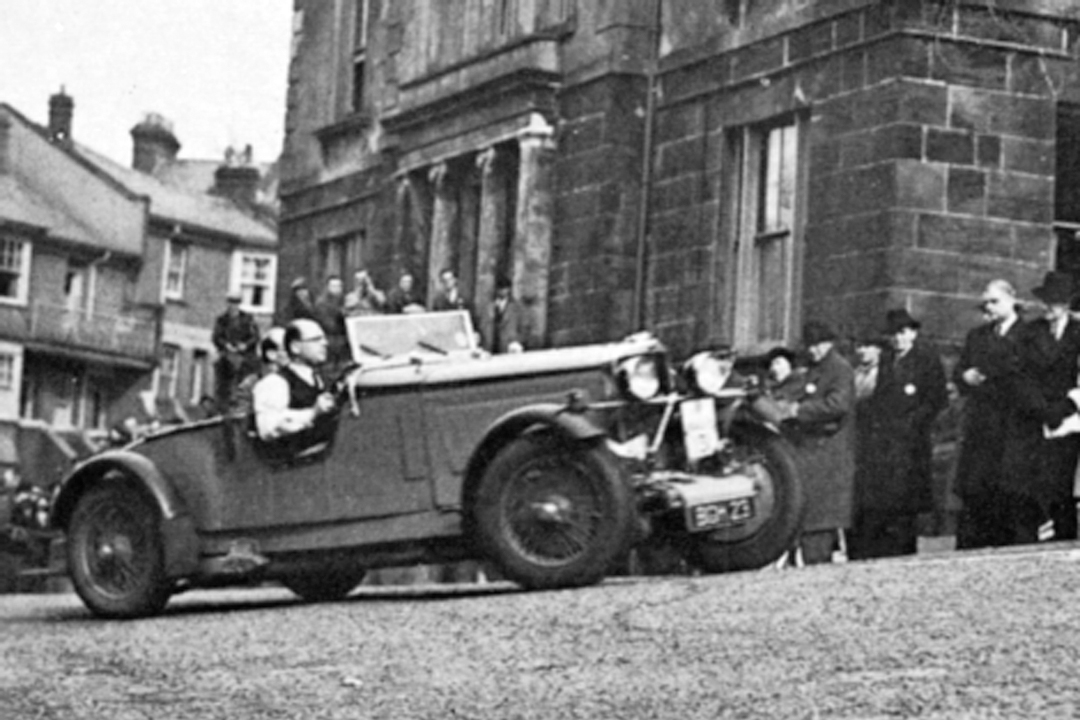

Many people did not know about the company’s dire financial situation, and some in the firm were thinking there could be a proper return to racing. A works supported 105 contested the RAC Rally but another competition venture was being hatched. Privateer Mike Couper, knowing that there was no going back to the glory days of the Fox and Nicholls racing team, proposed a works-supported attempt on the 1934 Alpine Trial. Three 105s were built…BGH 21, BGH 22, and BGH 23, the latter being team leader Couper’s own car. All this was going on while the liquidators were wandering around the factory. No one could imagine not only what would happen at the Alpine Trial, but also that BGH 23…Big Talbot…would continue to race and become the fastest touring car in the world at the time.

Several rally drivers had appeared at the London Talbot premises hoping to get a car for the Trial, and those most likely were Tommy and Elsie “Bill” Wisdom, and Hugh Eaton. Couper managed to persuade Talbot that, with the new pre-selector box, the 105 in its fourth year of production was still a force to be reckoned with. It was agreed that Pass and Joyce would pay for the cars and Mike Couper would be team leader. The three new chassis were built in the early summer, along with several other special cars for other private competitors in a range of events. The cars looked very much like their predecessors, and the new gearbox was not especially evident in terms of appearance. BGH 21 was assigned to the Wisdoms, BGH 22 to Eaton and Ben Higgins, and BGH 23 to Couper and George Day. The Trial consisted of day after day of high-average speed slogs over steep passes in the Alps, even higher speed trials in traffic on the Italian autostradas…68 mph average for many, many miles, all after having been driven down to the start at Nice, from London.

It would take two more issues of VR to tell the tales of the 1934 Trial, but the Talbot Team took the Alpine Cup and the team prize, with no loss of marks. This was a stunning effort, and it ensured that despite the purchase of the Company by Rootes, Talbot 105s would go on racing for some years.

In 1934, Mike Couper took BGH 23 to scratch, handicap, class and overall victories at Brooklands. He repeated this record through 1935 and, in 1936, set the fastest lap at 119 mph. He improved this to 123 mph in 1937 and went on winning into 1938, eventually setting a fastest lap in October 1938 of 129.7 mph, with a special aerodynamic cowling in place, thus becoming the fastest four-seater car ever to lap Brooklands. It was this record which insured that BGH 23 would always be known as Big Talbot.

Driving “Big Talbot”

Mike Couper sold BGH 23 in 1940 when it was converted into an “ugly two-seater” in 1945/46 by H.J. Ripley. It did a number of hill climbs and then disappeared, being found by Charles Mortimer as scrap in 1960. He restored it between 1961 and 1963, and it started a career in historic racing that is difficult to rival. BGH 21 and 22 also did some further competition, and eventually 22 and 23, as well as several of the “GO” cars, belonged to the world Talbot expert, Anthony Blight. BGH 23 won many races throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and Blight himself raced it many times. In recent years, John Ruston became the “other person” to own the significant Talbots…21, 22 and 23, campaigning them regularly at all the important historic events. Gareth Burnett saw close to 138 mph on the Mulsanne Straight in BGH 23 in 2004!

I had the chance to see BGH 21 “up close and quick” in the 2005 Tour Britannia, sitting next to Gareth Burnett not only on the road but on the demanding special stages, on gravel and grass, during several laps of Rockingham race circuit which was one of the stages, and in the hill climbs at Shelsley Walsh and Loton Park. I was just immensely impressed by how fast this then-71-year-old car could go. The handling was…spooky! We took a quick bend on the way to Rockingham too fast, and the corner tightened up, and I knew we were going off the road. I just spotted Gareth looking serious and smiling at the same time, as he sawed away, stamped the throttle and somehow pulled it through the corner. After losing time to repair the bands inside the gearbox, we were making up time heading north toward Loton Park. If the brakes had failed, Shrewsbury wouldn’t be there today!

Earlier this year, Gareth put me in the BGH 23 to test it for myself, though it was on public roads, and a bit damp. Big Talbot is quicker. The car feels far more modern than it should. The steering is very positive; there is no major rattling as one might expect, but the torque is the key commodity…it can get you out of any situation. The brakes just couldn’t be those of a 70-year old. The chassis stiffness, and all that power, mean that everything is predictable. The low-spring rates insure responsive handling and comfort.

I have had a chance to try pre-selector boxes, and this was by far the easiest. I find it difficult to ignore the clutch in traditional fashion, but the adjustment is made fairly quickly…select the gear you want and when the moment is right, dip the clutch. The change is smoothness itself. In race or rally conditions, this means getting the gear change done before getting into the corner and using all your energy and concentration on getting a fairly large car through a corner as fast as possible. The car is very comfortable to work with, and somehow the seats support you without belts, though in race conditions, the lack of belts and rollbar at over 120 mph took a bit of getting used to!

It was quite possible, even in the damp, to attack corners and roundabouts and let the torque make the car work at its best. At speed, the steering is impressively light, though less so when parking. Everything works as it should and my confidence grew rapidly as I explored the flexibility of the car, accelerating quickly even in top gear from low speeds. No wonder this production car did so well on something as car destroying as the Alpine Trial. The real wonder is that it was, and is, equally at home at Le Mans and Brooklands, that it could wind its way up and down the Stelvio Pass and set new records on the Mulsanne and at Brooklands, that it keeps doing it today, and yet has changed little. It gets loving attention from GBRacing, and John Ruston insists his cars are set up perfectly.

Buying and Maintaining a Talbot 105

There are examples of original team Alfas and Bentleys still around and still for sale. They cost millions. As already mentioned, GO 54 will have been up for auction by H & H Classics in the UK by the time you read this. That car placed 3rd at Le Mans in 1932 in the hands of Tim Rose Richards and the Hon. Brian Lewis. It ran at the Tourist Trophy in 1932 and again in 1934, after the Team cars had conquered the Alpine Trial. GO 54 has a replacement engine but remains essentially original. It belonged to Anthony Blight for many years, and has always been well looked after. Most of the pale green Team Talbot cars have continued to compete and thus have been carefully maintained, and fortunately there is considerable prewar Talbot knowledge about. For what it is, that makes the estimate quite reasonable. Big Talbot, BGH 23, should be worth some fair amount more. Shortly after our test, BGH 23 was sold to German enthusiast Michael Strasoldo, such is the resurgence of interest in Talbots in Europe. It is still prepared and raced by Gareth and by himself. Strasoldi’s first outing at Spa getting his 2nd place behind an Alta—in Gareth’s hands. Watching the car at the Le Mans Classic a few months ago made me very aware how much I had been missing in not knowing more about Talbots earlier.

Specifications

Chassis: Pressed steel side members;

Wheelbase: 9 ft 6 in

Track: Front and rear – 4 ft 7 in

Suspension: Semi-elliptic front and rear springs; hydraulic dampers

Engine: 6-cylinders

Capacity: 3.3-liters

Bore and stroke: 80 x 112 mm.

Compression ratio: 11.4 to 1

Power: 164 bhp @ 4800 rpm

Carburetion: Zenith downdraft or Twin or Triple SUs

Gearbox: Wilson pre-selector 4-speed from 1932

Final drive: Torque tube

Brakes: Cable-operated drums

Resources

We are very grateful to John Ruston for the use of his car and for his custodianship of history, and to Gareth Burnett for his help and good driving! (www.gbraceengineering.com)

Thanks also to H & H (www.classic-auctions.com)

Blight, A. Georges Roesch and the Invincible Talbot. Grenville Publishing, London, 1970.