BMW CSL

In the world of production sedans – touring cars, as they are known in Europe – few if any cars have ever been designed with racing in mind. Like a street fighter, they are born into this world with a certain set of abilities and skills that may not be conducive to battle. But as they mature, circumstance thrusts them into situations that force them to change – to evolve – into what ultimately is a completely different beast altogether. Such is the story of a pleasant little sedan from Bavaria that was thrust onto the mean streets of Spa, the Nurburgring and Le Mans and was forced to either evolve or be beaten to death by its enemy. This pleasant car was the BMW 2800 CS or “Coupe,” but the car that it would ultimately become was the 3.0 CSL “Batmobile” – the Bavarian Brawler.

In 1965, Bavarian Motor Works (BMW) built a mid-size Karmann coupe powered by the company’s tried and true 2.0-liter inline 4-cylinder engine that was the mainstay of its 1600-2002 line of small, economical sedans. While the critics raved about its styling and appointments, their biggest criticism was for the Coupe’s substantial lack of power and performance. So in 1968, BMW developed a 2.5 and 2.8-liter inline 6-cylinder motor (slanted at 30 degrees) for the Coupe, which produced 170 bhp. As has been BMW’s way throughout its history, the company leadership felt that the best way to prove the Coupe’s increased performance would be through competition. At the time, the most competitive and challenging series for a production car in Europe was the FIA European Touring Car Championship (ETC).

BMW chose to homologate the 2800 CS in the ETC Group 2 category for sedans where at least 1000 examples had to be made in the previous model year. Rules for the category were fairly broad, with engine improvements allowed, provided the original layout (# of cylinders and configuration) were not altered from the production version. While the original block, crank and head had to be used as starting materials, these could be significantly modified with most other parts being free for upgrade or replacement. Suspension design was similarly free, provided that the original production design (i.e. independent, torsion bar, etc.) was maintained.

As for the body, no modifications were permitted to the structural design of the body shell other than a roll cage. However, lightweight panels could be used if at least 100 street versions also incorporated the new panels. As for aerodynamics, the FIA rules were rather vague. The rules stated that fender flares and spoilers were allowable, but certainly no one at the FIA could have foreseen the loophole that they would leave open for the BMW engineers in the years to come.

Rather than commit to a full-scale factory effort (which BMW was already pursuing in Formula 2), BMW decided to enlist the aid of a German tuning house called Alpina to race prepare the 2800 CS. Alpina, under the direction of Burkard Bovensiepen, balanced and blueprinted the 2.8-liter motor and entered the near-stock 2800 in its first race at the 1969 24-Hours of Spa. In practice, it became readily apparent that the overweight and underpowered Coupe was going to be no match for the then dominant 2.6-liter, V-6 Capris produced by Ford of Germany. Though not nearly as fast, the Alpina-prepared Coupe soldiered along (devouring 40 tires in the process!) and finished the grueling 24-hour race a respectable ninth overall in its first race outing. Alpina continued to race the near-stock 2800 throughout 1970, scoring a couple of victories, including an overall win in the following year’s 24-Hours of Spa race.

1971 would see the addition of a second German privateer team to race the BMW Coupe lead by tuner Josef Schnitzer. Like Alpina, Schnitzer had a long working relationship “hot-rodding” BMWs and was anxious to be the team to hand BMW the European Touring Car Championship. Additionally, in 1971, BMW increased the homologated displacement of the Coupe from 2.8 to 3.0-liters and added Kugelfischer mechanical fuel injection in an attempt to close the performance gap with Ford. In its new guise, as the 3.0 CS, the BMW coupe was benefiting from increased power, but was still significantly overweight compared to the Capris. However, this year would mark a breakthrough for BMW as Dieter Quester, in one of the Schnitzer-prepared Coupes, handed the Capris their first defeat at the horsepower-favoring Zandvoort circuit in Holland. Even with this first success, the engineers at BMW realized that in order for the 3.0 CS to be truly competitive with the Capris, the car was going to have to go on a serious diet.

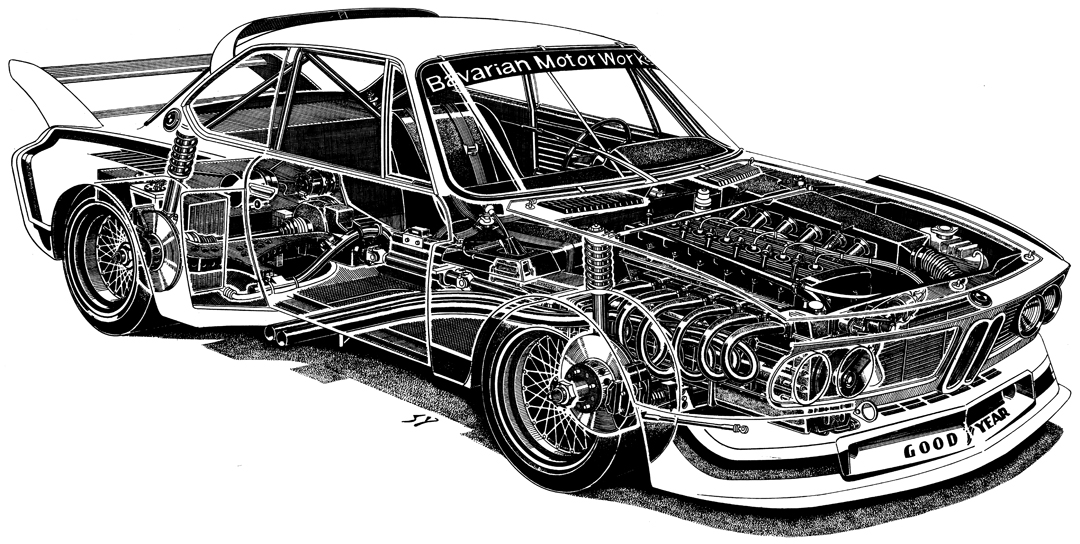

In order for a lightweight version of the Coupe to be homologated for the 1973 season, BMW had to produce 1000 lightweight production cars for 1972. These new cars were similar in build and construction to their 2800 and 3.0 CS predecessors in that they employed independent front suspension with McPherson struts and integral coils, lower control arms, and an anti-sway bar. At the rear were semi-trailing swing arms with progressive coils, gas shocks and an anti-sway bar. Weight was saved by creating a body shell made of thinner gauge steel combined with new doors, hood and rear deck lids made of thin aluminum. All told, over 500 pounds were dropped from the CS, which was now renamed the 3.0 CSL (L for leightgemetal or light).

The end of 1972 also saw a number of organizational changes at BMW, which would completely change its fortunes in European Touring Car racing. The leadership at BMW (most notably, then deputy director Bob Lutz, who would go on to become chairman of Chrysler) decided that it was time for an official factory CSL racing effort, in addition to those of independents Alpina and Schnitzer. In order to achieve the success that BMW so badly desired, Lutz approached Ford of Germany racing director Jochen Neerspach and his engineering director Martin Braungart about a defection to BMW. By May 1972, the Ford duo agreed and had but a scant four months to prepare the factory racing CSL program for 1973. In that time, the new lightweight racecar also received a redesigned suspension with new McPherson struts, trailing arms, steel hubs, center locking rims and new larger brakes from Ate. The new-and-improved CSL also sported an entirely revised drivetrain starting with a 3.3-liter motor pushing 350 hp through a new Getrag 5-speed gearbox. This new performance package was clothed in an even lighter body, which now had sprung fiberglass, flared fenders and an enormous front-air dam that hung down to the ground like a curtain. The new CSL racecar was tested at Hockenheim by Toine Hezemans and showed tremendous improvement over its heavier forebear. The stage was set for a remarkable 1973 title bout.

In this Corner…

For 1973, the factory team, now known as BMW Motorsport GmbH, fielded 5 CSLs for the star-studded team of Chris Amon, Dieter Quester, Toine Hezemans, Hans Stuck and Harald Menzel. This effort was in addition to the Alpina-prepared cars for Niki Lauda/Brian Muir, Gerold Prankl/Jean-Pierre Jarier and the two Schnitzer-prepared CSLs driven by the likes of Bob Wollek, Henri Pescarolo, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud and Walter Brun (with occasional appearances by Jackie Ickx, Rolf Stommelen and the Brambilla brothers, Vittorio and Ernesto). This epic lineup would battle against a Ford all-star team lead by Jackie Stewart, Emerson Fittipaldi, John Fitzpatrick and Jody Scheckter.

The opening round of the 1973 Ford/BMW championship fight took place at Monza in March. While the factory 3.3 CSLs were sidelined early on with mechanical troubles, the 3.0-liter Alpina team of Niki Lauda and Brian Muir outlasted the Fords to claim victory and first blood. A pair of cancelled events meant that the next round of the conflict would not be held until April at the Nurburgring for the German Touring Car Championship. Here, the factory CSL of Toine Hezemans claimed victory despite heavy attrition that resulted in, among other things, the total destruction of Brian Muir’s Alpina CSL. BMW was again victorious at the following nonchampionship race at Spa where Niki Lauda teamed with Hans Stuck for the victory. However, the following Championship round at the Salzburgring in Austria saw Ford even the FIA Championship at one race apiece when the team of Glemser and Fitzpatrick routed the field for the win.

Next, BMW entered a pair of factory-supported CSLs for the 1973 24-Hours of Le Mans. Driven by Chris Amon/Hans Stuck and Dieter Quester/Toine Hezemans, the CSLs competed against three factory-backed Ford Capris sent to snatch away the sedan category. Gearbox trouble slowed the Stuck/Amon car, which ultimately resulted in Stuck spearing his CSL into an errant Ferrari during the night. However, the Quester/Hezemans car soldiered on as, one by one, the Fords succumbed to valve train failure (the Capri’s “Achilles Heel” throughout the 1973 season). Quester/Hezemans finished the French classic 11th overall and first in the sedan class.

By midseason, Neerspach and his team at BMW realized that the ’73 championship was going to be too close to call, unless they could come up with a technological advantage to tip the balance in BMW’s favor. The “unfair advantage” that the Munich engineers were looking for was ultimately found in the FIA rulebook! The FIA rules governing production car racing stated that evolutionary changes to the design of a homologated car could be updated midyear. One of the most significant problems that the CSL had always struggled with was high-speed instability. This instability stemmed from the fact that at high speed, the CSL was generating over 60 kgs of lift at the rear of the car. So, in a move reminiscent of that seen in the NASCAR Dodge Chargers of 1970, BMW designed a special aerodynamic kit to be sold with new production CSLs. This kit included a large chin spoiler, fender-mounted air splitters, a monstrous rear deck lid-mounted wing and a roof spoiler, which diverted air downwards over the new wing. The outlandish look of the enormous wing and spoiler prompted many to nickname the CSL the “Batmobile” (a name which is commonly used to refer to the winged CSLs still to this day).

In wind tunnel testing at Stuttgart, the new “aero” package converted the 60 kgs of rear lift to 30 kgs of downforce. In track testing, this new configuration allowed Jochen Mass to shave over 15 seconds off the CSLs best time on the Nurburgring’s Nordschleife circuit. With this significant improvement, BMW was worried that if Ford were to learn of BMW’s new aerodynamic package, it would try to homologate a similar package for the Capri. In order to avoid this, BMW cleverly waited to submit its homologation request until the very last moment of the last month of the year that the request could be accepted. By the time Ford learned of the changes, it was too late to file its own update; it would have to wait until the next racing season!

Photo: VRJ Archive

The new Batmobile made its race debut at the prestigious 6-Hours of the Nurburgring. BMW demoralized the Ford opposition with a resounding 1-2-3 finish – Stuck/Amon leading home Hezemans/Quester/Menzel from Lauda/Joisten in the Alpina entry. BMW went on to take the top three qualifying positions for the 24-Hours of Spa with the race victory going to the factory team of Quester/Hezemans (the Alpina team withdrew after Hans-Peter Joisten was killed in an accident). The pair of Quester and Hezemans went on to win subsequent rounds at Zandvoort, Holland, and Paul Ricard, France, to hand BMW the prestigious FIA European Touring Car Championship and Toine Hezemans the driver’s championship.

The following year, BMW returned to the ETC with a 60 kg lighter CSL, which now sported a new 24-valve head that was capable of churning out over 400 hp. Ford, not surprisingly, had homologated its own winged variant of the Capri, termed the RS 3100. This new car sported a massive rear deck lid wing (a la BMW) and an improved motor with over 400 hp. Unfortunately, 1974 was also the year of the OPEC oil embargo. With Germany being one of the hardest hit countries by the fuel shortage, public opinion was not in favor of flame-breathing, gas-guzzling, 400-hp touring cars racing around Europe, while the people stood in long lines for gas rationing. Resultantly, these cars would only face off a couple of times through the course of the year, with the results being again very close. BMW was able to claim victories at Monza (privateers Lafosse/Peltier) and the Salzburgring (Stuck/Ickx). With neither team willing to incur the public wrath of running the “big cars”, Ford ended up winning the championship with a fleet of 2.0-liter Escort “economy” cars.

In 1975, the factory kept a relatively low profile, leaving most of the racing to the privateer teams. Four of nine German qualifying races were won by CSLs that year, including the coveted Nurburgring 6-Hours (CSLs went on to win this event for four consecutive years from ’75-’79). At Le Mans, a Group 2 CSL, painted by famed artist Alexander Calder and driven by Sam Posey and Herve Poulain, was leading its class and running an impressive fifth overall. Unfortunately, this brilliant run would end prematurely when the engine came apart in the early evening. In the final analysis, the Schnitzer team featured prominently that season, with driver Alfred Krebs taking three overall victories and nearly snatching the championship were it not for a blown engine in the final race at Hockenheim. However, 1975 would prove significant in that it saw the debut of a new opponent in the form of the brutally fast Porsche 911 RSR Turbos. During the course of the next several years, the Porsche Turbos (911 & 935) would replace Ford as BMW’s primary championship competitors. This was demonstrated in ’75 when losing the manufacturer’s title to Porsche in both Europe and America would ultimately drive the BMW Motorsport engineers to create their final and most frightening iteration of the CSL for 1976. In the eyes of BMW, there would be only one way to defeat a turbocharged Porsche – a turbocharged BMW.

In 1976, BMW entered the inaugural Group 5 FIA World Manufacturer’s Championship with a 3.5-liter, turbocharged CSL that produced anywhere from 700-1000 hp, depending on boost! The car debuted at the May, Silverstone round in the hands of F1 stars Ronnie Petersen and Gunnar Nilsson. When asked about the turbo car’s debut, project engineer Braungart replied, “It was ridiculous, this car – the floor glowing with heat, no way to transmit power, and the wing on full-downforce position to try and keep the back on the ground. It was mad – but fun.” Despite the new turbo-CSL’s harsh characteristics, Petersen put the car on the front row and charged into the lead on the first lap. But as with most of the races that year, mechanical problems kept him from taking the checkered flag. In the end, the turbo-CSL lead its class at Le Mans and claimed three victories, but was unable to live up to its potential and snatch the championship from Porsche’s hands.

The Batmobile Comes to America

In late 1974, BMW reclaimed distribution rights in the US from previous importer Max Hoffman and was keen to establish its own stateside identity. Resultantly, 1975 saw the introduction of four factory ’74 spec CSLs to compete in the IMSA GT Championship. The BMW Motorsport Group set up operations in, of all places, Bobby Allison’s NASCAR shop in Hueytown, Alabama, and brought over Hans Stuck to drive with Sam Posey, Brian Redman and Allan Moffat. The team’s first foray was the 24-Hours of Daytona, which ended early with the sole Stuck/Posey car out with engine trouble. But the team quickly bounced back and put on a brilliant performance at that year’s 12-Hours of Sebring.

Utilizing a classic tortoise-and-hare scheme, Stuck and Posey set off at a blazing pace in the hopes of racing the competition into early retirement. They were successful, but their own car was not able to take the strain and was forced to retire. The pair then joined the team of Brian Redman and Allan Moffat in the sister car and helped drive it to a brilliant overall win. The season was capped off by a victory in class at the season-ending Watkins Glen event, but the championship would go to Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood in the Porsche 911 RSR.

1976 saw several changes in IMSA, not the least of which was the defection of Porsche stalwarts Gregg and Haywood to BMW, and the introduction of the awesome Porsche 935. Porsche and BMW battled tooth and nail all season long. For BMW, the team of Gregg, Redman and Fitzpatrick claimed the overall victory in the 1976 24-Hours of Daytona. The team of Gregg and Haywood went on to finish 7th at Sebring and 1st in class and 4th overall at the season-ending Watkins Glen round. Though extremely competitive, Porsche claimed the ’76 IMSA Championship and brought an end to the CSL’s brief factory race program in the US.

Never Too Old

By 1977, the factory’s racing interests had moved onto its new 320 series of cars. However, independent teams continued to race the CSL with tremendous success for the next three years. Most notable was the Alpina team’s campaign in the 1977 ETC against a well-funded and powerful team of Broadspeed-prepared V-12 Jaguar XJ12 sedans. Despite having smaller engines, smaller budgets and battling against a factory-supported team, the Grosser-Beer-sponsored CSL of Dieter Quester claimed five victories and the ETC Championship. Amazingly, two years later in 1979, this same car reclaimed the ETC title by winning seven of thirteen rounds in the hands of Italian racers Facetti and Finotto. In the harsh light of today’s racing environment, where cars are nearly obsolete by midseason, it seems almost impossible that the BMW Coupe/CSL line of cars were able to remain internationally competitive for over 10 years!

Buyer’s Guide

Due to the ready availability of aftermarket parts for the CSL (including spoilers, fiberglass fender flares and rear wings), it is of utmost importance to verify the provenance of any racing CSL before considering a purchase. Once a car’s history is established, the next area of potential concern is the body. As with most early ’70s production cars, rust is a potential problem. In the case of the CSL, rust-prone areas include sills, rear quarter panels, A-pillars, A-post and wheel arches. General parts availability is good; however, specialized engine parts, such as the 24-valve head and the Kugelfischer injection system found on later cars, are hard to find and very expensive.

Prices for the racing CSL vary, depending on specification and history. Early 3.0-liter models start in the range of $75,000 depending on race history. Later models, such as the 3.5-liter Group 5 cars will start closer to $125,000 due to their increased performance and technical sophistication. As with most vintage racecars, a significant race history can dramatically increase the value of a CSL.

Photo: Ferret Fotographic

Specifications

Examples: CSL: 1056 street CSLs, 156 “Batmobile” CSLs

Length: 15’ 3.25”

Wheelbase: 103.3”

Height: 4’ 5.5”

Weight: 2370 lbs. (1977 spec.)

Suspension: Front: Inclined McPherson struts with integral coils, lower control arms and anti-sway bar. Rear: Semi-trailing swing arm, progressive coils, gas shocks and anti-sway bar..

Engine Type: Cast-iron inline-6, slanted at 30 degrees with either alloy 12-valve SOHC or 24-valve DOHC head. Kugelfischer mechanical fuel injection.

Displacement: 3192 cc. (1977 spec.)

Bore and Stroke: 89.8mm. x 84mm. (1977 spec.)

Compression: 11 to 1 (1977 spec)

Horsepower: 325 hp @ 8000 rpm (wet sump). (1977 spec.). 340 hp @ 8000 rpm (dry sump). (1977 spec.)

Transmission: Getrag 5-speed with reverse.

Rear End: 75% limited-slip differential.

Brakes: Front: 13” ventilated disc. Rear: 11” ventilated disc.

Wheels: Front: 16” x 10.5” (1977 spec.). Rear: 16” x 12.5” (1977 spec.)

Bodywork: Steel unibody with aluminum panels.

Resources

Unbeatable BMW: Eighty years of engineering and motorsports success.

Jeremy Walton

Robert Bentley, 1998

ISBN-0-8376-0206-8

BMW vs. Ford

Jonathon Thompson

Road & Track, 1973

Time and Two Seats

Janos Wimpffen

Motorsport Research Group, 1999

ISBN-0-9672252-0-5

Munich Legends

Tony Halse

Chetwood Gate, Sussex RH17 7DE, UK

(0) 1825 740456, (0) 1825 740094 FAX

Parts, Racecars, Information.

RC Motorsports

Carl Nelson

710 Turquoise St.

San Diego, CA 92109

(619) 488-1555, (619) 488-0972

Parts, Preparation, Information.