Lotus 30

The Lotus 30 was built for all the wrong reasons. Colin Chapman designed it basically to get even with Eric Broadley for “stealing” the Ford prototype program. Even the premise – light weight and low frontal area at any cost – proved to be fatally flawed. Instead of a revenge weapon, the Lotus 30 became the laughing stock of big-bore sports car racing and the program ended in failure. And yet today the few good examples left command similar prices to proven winners from McLaren and Lola. The tale of the 30 is an interesting one, proof that genius is no substitute for a thorough development program.

The Lotus 30 story began, surprisingly, in Italy in 1963. Purchase negotiations between Ford and Ferrari collapsed over control of the racing team, and the Blue Oval guys retreated to Dearborn to lick their wounds and plan an attack. If they couldn’t buy Ferrari, they planned to beat them fair and square (or any other way, for that matter). At the time Ford didn’t have credentials of their own, having only limited involvement in the Shelby Cobra project. The most obvious outsider who could be brought in was Chapman, who was already running their Indy program but had yet to taste success. Chapman thought he had the project in his pocket, but when Lola introduced their Mk.6 GT in 1963, Ford took notice.

Here was a modern, mid-engined racing car with one of their beloved 289 V-8s already in place, and so Ford opted for a contract with Lola boss Eric Broadley. Later, Broadley would be forced out after a power struggle with John Wyer, but in 1963, Chapman felt that he had been slighted and wanted to show that he could build a faster Ford-powered sports racer.

With stiff competition from Cooper, Chaparral, McLaren, Genie and others, the future of powerhouse V-8 sports-racing cars looked bright and seemed a natural arena for Chapman to display his artistry. A number of Lotus 19s had been successfully re-engined with V-8s, and Dan Gurney’s 19B was even purpose-built for the small-block Ford. But while the 19 used a conventional space frame, the 30 would be very different. Designed primarily by Chapman, the 30 was based on an ultra-light backbone frame skinned with 20-gauge steel sheet. In general, it resembled the Lotus Elan frame, with a “Y” at the back to support the engine and rear suspension, and double wishbones with coil-over shock units up front. Steering was via a modified Alford and Alder rack (similar to Triumph) and the hub carriers were cast from magnesium. The rear suspension was set for 2 degrees negative static camber and the rear roll center was less than three inches above ground level. A 13-gallon rubber fuel tank was enclosed in the backbone, with provision for additional 9-gallon bladders in the fiberglass body. Total weight was an impressive 1,400 pounds.

In order to reduce frontal area, Chapman made mistake #1 by choosing short 13” wheels to take 6.00 tires in front and 7.00 in back. The idea was to reduce unsprung weight and cut frontal area, but the payoff was too high. The short wheels limited the size of the brakes that could be fitted, and, unknown at the time, future tire development would be directed towards 15” rubber. The tiny 10.5” Girling disc brakes would prove to be hopelessly inadequate for use on a serious ground-pounder.

If races were won on looks, the 30 would have been a champion. The stunning body was low and sleek, courtesy of its short tires and plexiglass headlight covers, and a rudimentary driver’s-side roll bar. In order to get a lower, smoother nose, two small (8” X 15”) radiators were installed, one in each front wheel arch fed by a plenum chamber behind two small air intakes in the nose. The 30 was introduced to the world at the 1964 London Racing Car Show but in an incomplete state. Chapman and Lotus were behind schedule, leaving little time for development.

More Promise Than Payoff

Unfortunately for Lotus, races are won on the track, not at a concours, and the 30 was doomed from the outset. Had there been a solitary works car, this would not have been so damaging to the Lotus reputation; but with 21 of these Series I cars sold to privateers, the project proved to be a public relations disaster. Priced at a reasonable £3495 in kit form, they were sold on the strength of the Lotus reputation.

New cars were ordered by many Lotus stalwarts including Ian Walker, who got the first one (#30/L/1). It was hastily completed in the paddock the morning of the 1964 Aintree 200 meeting and entered for Jim Clark. Of course, no car was so bad that Jimmy Clark couldn’t make it a winner… or so the thinking went. Clark started from the rear of the grid and worked his way up to an astonishing second overall behind Bruce McLaren’s Zerex Special. The future looked bright, but persistent cooling problems plagued the 30s throughout 1964. The two tiny radiators were just not up to the job, although a change in plumbing helped some. Later in the season, Walker’s regular driver Tony Hegbourne wrote the first car off at Brands Hatch. A works car (30/L/2) was built for Clark to run the rest of the season, and David Prophet picked up one to race in South Africa.

Photo: Bob Tronolone

Clark crossed the pond to run a fuel-injected 30 at the 1964 Riverside Times Grand Prix, where he finished a creditable third behind Parnelli Jones (King Cobra) and Roger Penske (Chaparral II). However, James Crow, covering the race for Road & Track, noted, “If it hadn’t been the fabulous Lotus 30 designed by the fabulous Colin Chapman, I would have said it handled like a pig. And another 30, which arrived for Mike Spence to drive, gave off such a strong odor of pork that Mike couldn’t even get it into the race.” David E. Davis (writing for Car and Driver) compared the Chaparrals to the Lotus, “They make the highly-touted Lotus 30 look like a Ford Tri-Motor among a flock of Boeing 727s.”

The subsequent professional race was the Monterey GP at Laguna Seca, where Bill Krause drove the ex-Clark 30 to a fine fourth in the first heat, but retired in the second with suspension failure. Also in the U.S., John “Bat” Masterson bought an early model and promptly wrote it off in his first race with the new car. Four new 30s were sold by dealer Lotus Southwest (30/L/6, 30/L/8, 30/L/12, 30/L/14), with #8 going to LeRoy Melcher who ran it in SCCA events in the Texas area.

One team owner who had great expectations for his new 30 (30/L/5) was J. Frank Harrison, who had fielded a highly competitive Lotus 19/Ford as well as many Indy cars. Crew chief Jerry Eisert had transformed their 19 into a ground-pounder by swapping in a hot 289 and fitting a streamlined bodyshell. Driver Lloyd Ruby had won the 1963 Kent pro race in it, and the team was sure that the great Colin Chapman could certainly better their efforts. They were wrong. When they got the new car, they were very disappointed and came to the conclusion that it was never going to be as good as their old 19. In the meantime, Eisert made a metal bellypan and added numerous large-diameter tubes to the rear structure to stiffen up the chassis. Finally, they gave up and never ran the car again, selling it to someone who intended to put it on the street.

Back in the U.K., Clark actually led the Tourist Trophy until suspension failure dropped him to 12th. After evaluating the results obtained with the first three cars, Lotus switched to thicker 18-gauge paneling on the chassis. At some point a full-width roll bar replaced the puny single-sided model the early cars were equipped with (in fact, when the prototype had run at Aintree, it had no roll bar at all).

Second Season

Big-bore (Group 7) racing heated up in 1965, with new customer cars from McLaren and Lola that outstripped the Lotus 30. Chapman responded with the Series II model, of which 10 were built with an even stiffer chassis. In order to speed up gear ratio changes, the center section of the bridge which carried the rear suspension was now made detachable. Ventilated discs were added to help stopping power and 15” wheels wearing Dunlop R7s replaced the 13” rims. These Series II cars are identifiable by a 30/S2/XX chassis number sequence that replaced the 30/L/XX sequence used on the Series I cars.

Photo: Harold Pace

Fat lot of good it did them. Although the S2 was much improved, it was still not enough to keep up with the revolutionary new Lola T-70, which not only put the Lotus on the trailer, but the McLaren Mk.1 and the King Cobra as well. In addition to the Lotus’ chassis problems, the Ford engine was now down on power to the Chevy used in the Lolas and heavier than the alloy Olds used in the McLarens. Lotus was not in a position to give the cars the development they needed, as they had their hands full sweeping up the 1965 Formula One World Championship and Indianapolis with Mr. Clark at the helm.

Clark put in some inspired drives in the works S2, actually winning a race at Silverstone in the pouring rain (yikes!). However, the level of competition can be judged by the third-place car, a front-engined Lola-Climax. The works 30 was soon beefed up with a highly tuned 5.3-liter Ford engine. Clark also picked up a win at Goodwood on Easter Monday, but failed to impress elsewhere.

In a last-ditch effort, Lotus built three of the now infamous Lotus 40s, which Ritchie Ginther referred to as “a Lotus 30 with 10 more mistakes.” The chassis and suspension were beefed up yet again, and the anemic 289 engine was replaced with a mighty 450-hp, 351-cubic-inch Ford. The ZF box got the heave-ho in favor of a Hewland LG500, and the body was slightly revised, with the exhaust pipes coming out the rear engine cover. Larger 11.75” vented discs were added, and the body was modified with air pressure vents behind the wheels.

First outing for the new model was at the Austrian GP sports car race, where Mike Spence qualified on the pole and led for 13 laps until the big mill overheated. Clark took over at Brands Hatch where the shift linkage came loose and then the brakes gave out. Jack Sears wrecked one of the works 40s while tire testing and was injured so badly he retired from racing. However, Sears was one of the few drivers who actually liked the 30/S2, which he had tested earlier.

The wrecked 40 was patched up and shipped with a second works car to Riverside for the American pro season. A third 40 (resplendent in beautiful pale metallic blue) went to Holman & Moody to be prepared for A.J. Foyt. However, mechanic/driver Bob Tattersall wrecked Foyt’s car in practice, and Ginther retired the second works 40 while Clark took an excellent second overall to Hap Sharp’s thundering Chaparral! The Holman & Moody car was hastily thrown back together for Nassau, where it promptly broke apart early in the Governor’s Trophy race. Not long thereafter, the two works cars were put up for sale for £3,750 each. It was the end of the line for the big Lotus sports racers.

Amateur History

Photo: Harold Pace

Unlike most old racing cars, few Lotus 30s made the move down to amateur racing after their professional debuts. They started at the back and promptly disappeared…very few were seen, even in SCCA amateur racing, after 1965. Most of the surviving 30s were upgraded with 15” wheels and bigger engines and are sometimes referred to as Lotus 30/40s (although this was not a factory designation). Homer Rader owned Lotus Southwest and occasionally drove 30s in Texas SCCA events, along with customer Melcher. A few hung around in English club racing, while 30/S2/3 was converted to a street car by Franco Sbarro and 30/S2/9 was made into a single-seater in England. Several others were converted to street cars or parted out for their running gear.

When historic racing got going in the 1980s, old 30s started coming out of the woodwork. Freed from the stigma of having to be front-line race winners, their svelte lines could be appreciated for their own sake. And with some development, they proved to be much better cars than their record would have led one to believe. In particular, the 40 had the potential to be a good ride if properly prepared. If Chapman had lavished as much attention on the 30 as he did on the F1-winning 33B and the Indy champion 38, things might have been more difficult for Mssrs. Broadley and McLaren.

Dr. Julio Palmaz always loved the looks of the 30. So although he knows all the stories that follow these cars around, he has acquired two of them anyway. One is the Melcher car run out of Lotus Southwest, and the other, a Series 1 car, was a mystery when he first purchased it. Discovered in a dumpster in California in the 1980s, it had been stripped of its engine, gearbox, wheels, brakes and chassis plate. The chassis had been heavily reinforced with steel tubing in the engine compartment area, and a sturdy steel bellypan was bolted on the bottom to stiffen it up. Ford passenger car brakes replaced the early Girlings, and the only identifying mark was the original white paint on the deteriorating body.

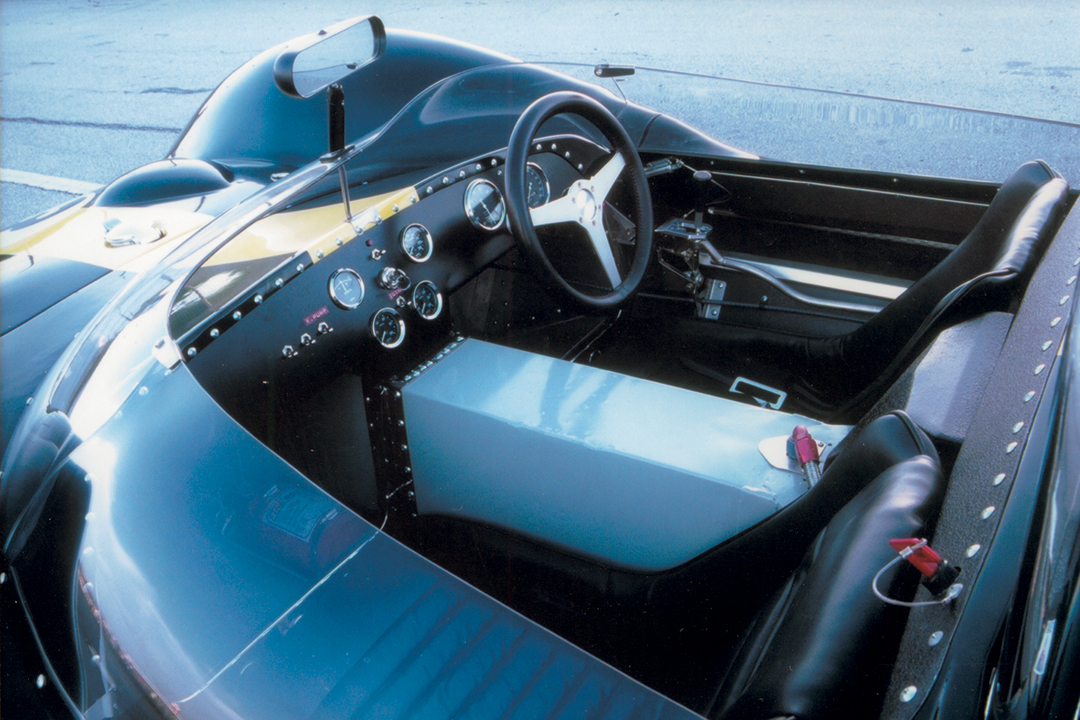

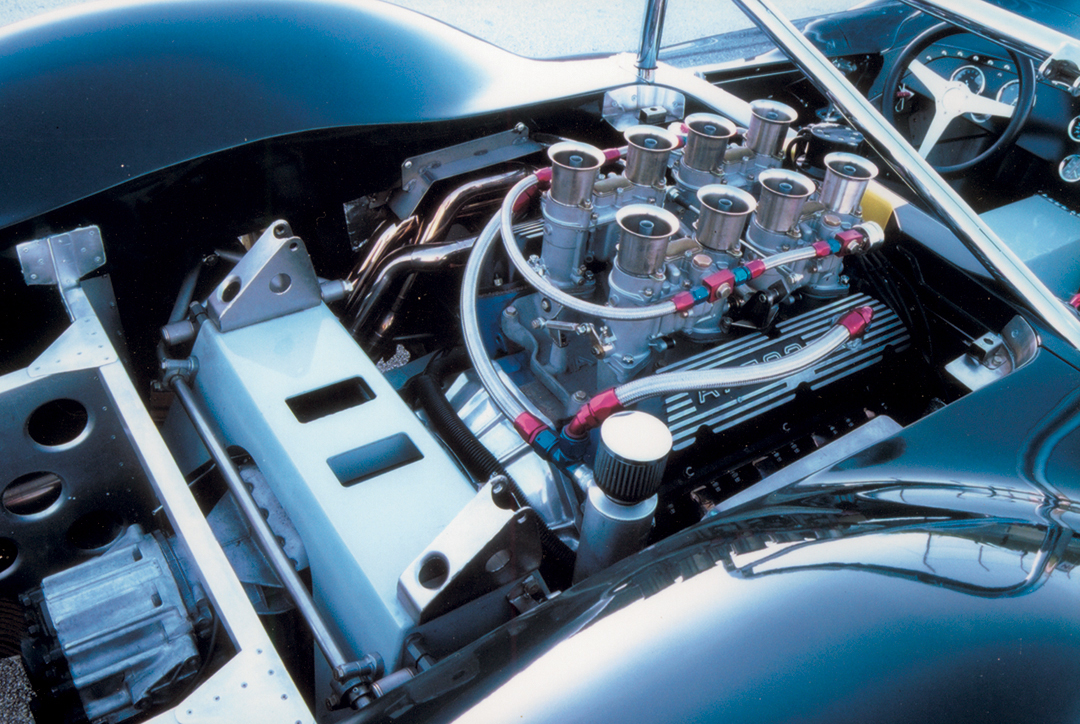

The car was accompanied by an incorrect history, misidentifying it as an ex-Foyt car. Not knowing which car he had, Palmaz had it restored at Huffaker engineering in Lotus green and yellow livery (a striking combination on this car). During the restoration it was found that the chassis was unwrecked (very odd for a 30) and with no corrosion. It was stripped and powder-coated, but the rear suspension towers were remade in stronger materials and the rubber fuel bags were replaced with a fuel cell. The suspension was remade to original dimensions in high-strength steel and new rotors, stub axles and bodywork were provided by Peter Denty in England, who has owned a 40 and assisted with the restoration of several 30s. The 13” wheels were crack tested and the magnesium uprights were replaced with new aluminum castings. A Ford small-block with four Webers was built up for reliability and with a broad power curve.

An Exciting Drive

Dr. Palmaz had kindly offered to let me try his beautiful brute (30/L/5) a year ago, but every time I got ready to climb into the seat, something would go wrong. At one race, it rained (I’ll leave that sort of thing to the J. Clarks of the world). At another, the engine expired after the first session. Finally, everything was up to snuff and I climbed into the cockpit for a spin around Texas World Speedway. I was pleasantly surprised at the amount of room, even for my six-foot-plus frame. The gearbox gate seemed a bit flimsy, but the gears were not hard to find. The lockout was a bit strange, requiring the driver to switch the gate over after shifting into second, so that first or reverse could not be engaged. It was also interesting to note that the 30 came with turn signals and a keyed ignition switch like a street car!

Once on the track, the 30 came alive. It is a bit twitchy, but the Huffaker-built engine, in a mild state of tune, is a good match for the somewhat limber chassis (although the Huffaker mods have surely helped). The steering is very quick but not overly so, and I was surprised at the amount of confidence it generated. Maybe Spence was right all along! For the first few laps, I took it very easy, getting everything up to temperature and making myself at home. Then I started picking up the pace (no pun intended) and really got going. As I rocketed onto the long banked straight, the 30 seemed to have proved its temperamental reputation a lie…and then it bit me. As I shifted up from third to fourth, the throttle suddenly hung wide open! The 30 was accelerating crazily down the straight as I completed the shift and reached for the ignition key. Suddenly, the accelerator pedal popped back up and the revs returned to normal. I drove to the pits on part throttle, where we discovered an errant bolt in the pedal assembly that was hanging on the pedal when it was fully depressed. A minor problem, quickly remedied, but enough to keep up the 30’s fearsome reputation as a car to be treated with great respect

Owning a Lotus 30

So how much is a 30 going for these days? Good question. Not many come on the market, but even a nonworks 30 will sell for over $100,000, and a full restoration can easily push the total price over twice that. Peter Denty advertised his restored ex-factory 40 (40/R/2) for £125,000 in 1996. However, it would be wise to have any 30 or 40 thoroughly gone through to make sure it is healthy – this is not a car for beginners and should be rigorously maintained. Although no competition for a well-driven McLaren or Lola, the 30 is still fun to drive within its limits and is one of the most beautiful racing cars of all times.

Photo: Bob Tronolone

Specifications

Model: Lotus 30 S1

Type: Sports-racing

Years of construction: 1964-1965

Production totals:: S1: 23. S2: 10

Chassis: Steel backbone

Suspension: Independent

Dry weight: 1,400 pounds

Engine: Ford 289” V-8

Oil system: Wet sump

Induction: Four 48mm Webers or T-J Fuel Injection

Horsepower: 360 hp @ 7,000 rpm

Brakes: S1: 10.5” solid-rotor discs. S2: 10.5” vented rotor discs

Wheels: S1: 13”. S2: 15”

Tires: Front: Dunlop 6.00. Rear: Dunlop 7.00

Gearbox: ZF 5DS20 5-speed transaxle

Resources

The World’s Racing Cars (1966 edition)

M.L. Twite

Specialist British Sports/Racing Cars

Anthony Pritchard

Road & Track

April 1964 (30)

Classic & Sportscar

July 1992 (40)

Car and Driver

January 1966 (40)

Sports Car Graphic October

1966 (PAM 30)

I would like to acknowledge the contribution of the late David Whiteside, who provided a complete list of Lotus 30 chassis numbers.