“Look at this!” Tracy shouted across the house. My wife’s swim coach voice was too enthusiastic to tarry, so I sprinted to the dining table to see her holding a battered, pulp classified tabloid. She held it up with an index finger firmly on a single ad at the top of a column. “Aston Martin DB2 Vantage, good condition, $15,000. Connecticut,” and a phone number. We called from the table. A week after the call I borrowed a trailer and headed for Connecticut.

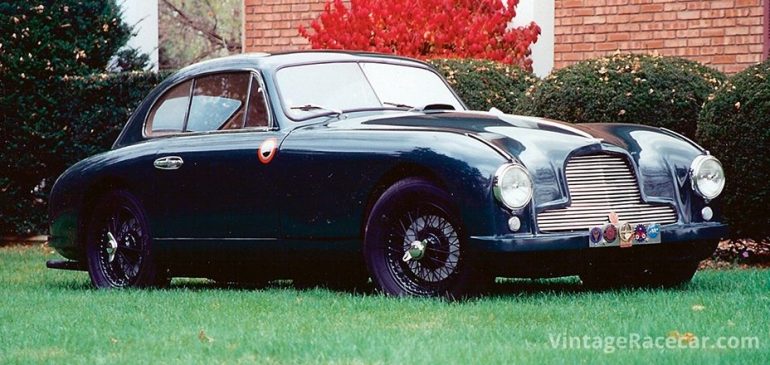

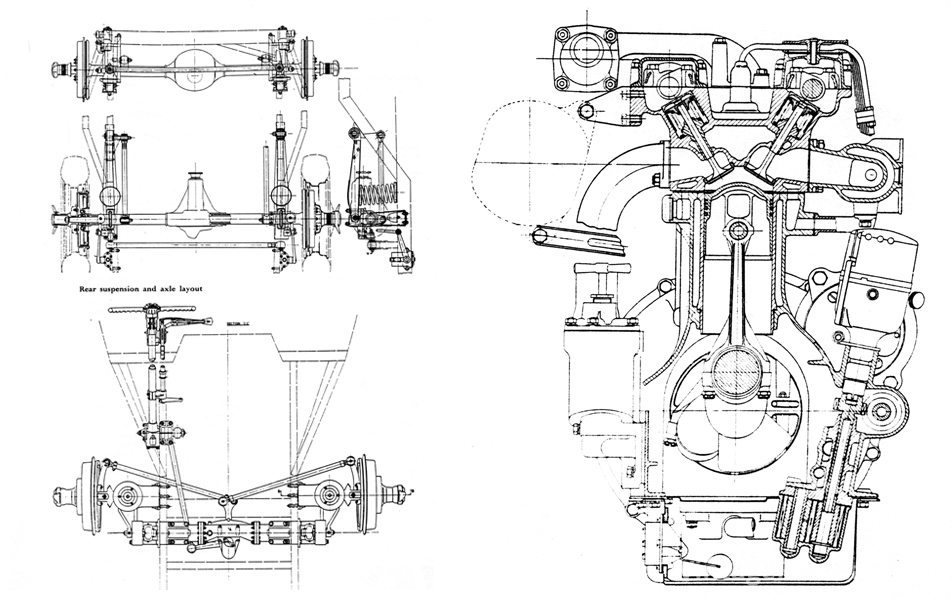

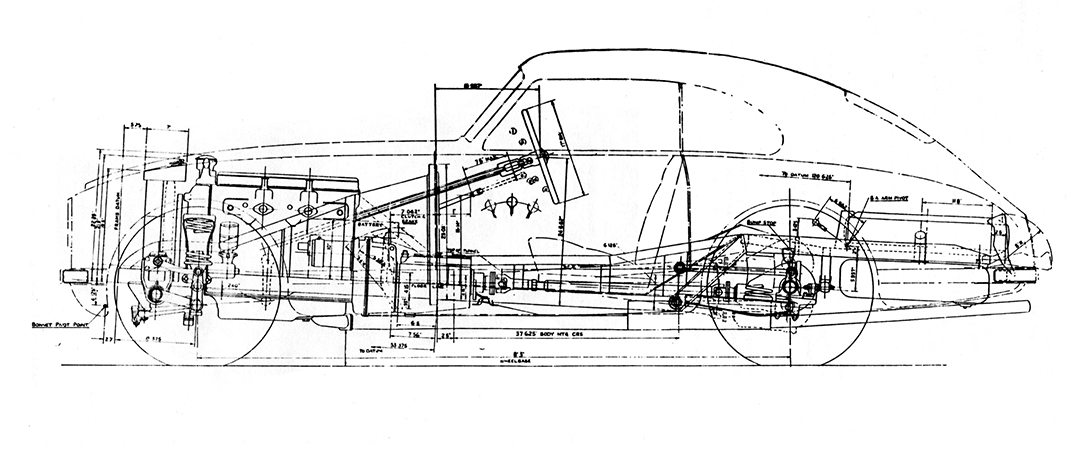

I had loved the DB2 Aston Martin for years. It seemed to be an affordable 6C 2500 Alfa Romeo with SU carbs. It had a beautifully engineered spaceframe, an inline-6, with DOHC that produced 125 hp in its Vantage form and came in 3rd overall at Le Mans in 1951. It looked like a Touring-bodied Alfa because David Brown had sent Frank Feeley to Carrozzeria Touring for inspiration and information about Carlo Felice Anderloni’s Superleggera lightweight body construction—small steel tubes and aluminum body panels. The DB2 weighed only 2500-pounds. Pure essence of Lionel Martin’s original dream; to create “A car that works like a Bugatti and is finished like a Rolls.”

S.C.H. Sammy Davis wrote in Autocar in 1970, “If ever a car owed its existence to enthusiasm, it is the Aston Martin.” He described Lionel Martin as, “…a big, intelligent and extremely well-mannered Etonian (Eton being in the pantheon of public schools for the English nobility).”

The esteemed Lionel Walter Birch Martin and Robert Bamford, a skilled engineer/fabricator, were Singer tuners and racers before the first Great War. They incorporated as Bamford & Martin in 1913 and had an Isotta Fraschini Voiturette chassis, with a Coventry-Simplex engine, on the road before the war began in August of 1914. In search of a marketable name, Martin’s wife, Katherine, suggested leading with the name of one of their favorite events at Aston Clinton, in Buckinghamshire, because it would move the car forward in any alphabetical list of car manufacturers.

Aston Martin was launched as a sporting manufacturer. The 1400-cc, side-valve engine was responsible for some international records and racing successes that carried the small firm along on the fine edge of collapse. When the team—continually involved in development with little effort toward sales—could no longer maintain the pretense of being in business, the solution walked in. It was 1926, the partners had searched for the perfect combination of technical and financial support for seven years when Augustus “Bert” Cesare Bertelli came into the Bamford & Martin shop with Lady Charwood and her son, The Honorable (soon to be Lord) John Benson, to bail them out and support a restart. Aston Martin was already known as a well-built sports and racing car, having sold about one car per year.

Bertelli called his new company Aston Martin Motors Limited, used his own new SOHC 1500-cc engine and built his first three Aston Martins in Woolf Barnato’s Lingfield home shop. Wealthy sportsmen surrounded the new team—pals supported the new car project by repeatedly ordering cars to keep the firm in business. Oddly enough, by the end of the ’20s, several of the same group had made themselves famous as the “Bentley Boys” while trying to support W.O. Bentley in the same way. Once again, a personal demand for excellence took Bertelli onto the path of the founders, and still more avid motoring enthusiasts were compelled to step in to keep the dream alive—for a while. This time, shipping magnate Sir Arthur Sutherland attached an IV line from his bank, put his son Gordon in as co-managing director with Bert to try to control the financial hemorrhage, and set about trying to sell some cars. They survived the depression with beautiful—and beautifully made—unprofitable sports cars, resulting in Bertelli leaving the firm. Claude Hill became chief designer in 1936, but with little resources, only the pedigree kept Aston Martin in the press and the hearts of sports car racing fans until finally, the reality of war superseded even the dreams of the most tunnel-visioned optimist.

to DB2 LML/50/316, and sends it to an enthusiastic new home.

“It was late in 1946 that I read an advertisement in The Times, offering a sports car company for sale.” Remembers David Brown, “I replied to the advert and, rather to my surprise, learnt the company was Aston Martin, which was quite a name even in those days. So I bought Aston Martin myself—completely outside the David Brown Company—for £20,000.”

A few months later he bought the Lagonda company as well and got with it the services of technical director W.O. Bentley—and his new 2.3-liter, DOHC, 6-cylinder engine. That engine was, in fact, the reason Mr. Brown bought Lagonda, Ltd. With Bentley’s exotic engine enlarged to 2.6-liters, a fine, new tubular spaceframe chassis by Claude Hill and a new Italian-inspired body designed by Frank Feeley, the DB2 became an immediate success. In 1952, it was advertised as “Race-bred luxury.”

New owner Phil Hill described his latest automotive love in a Motor Trend feature titled “My Choice—DB2” published in the February 1952 edition: “Before I actually bought the car, I checked it out for quality. The furnishings are Rolls-Royce-like in finish quality. To be truthful, I considered the price a little stiff at first. Jaguar sells the XK-120 for under $4,000 and the MG…costs less than $2,000. The Aston’s engine is about halfway between the two in size and the body is of Jag proportions.

“It wasn’t long before I had my answer. Just two crosstown jaunts, one of them out Sunset Boulevard to the ocean and back, convinced me the DB2 was something out of the ordinary. The cornering, for example, was fantastic. It’s the best cornering car I’ve had, and I’ve driven both standard and modified XK-120s in road races. Actually, the Aston corners similarly to the Alfa Romeo I owned (8C 2900 MM roadster), except it doesn’t have the peculiar oversteering tendencies that Alfa had with its swing axles.

“Before I bought the car, I checked it for quality. The furnishings are Rolls-Royce-like in character … The overall styling of the body is obviously of the modern Italian school, and the body panels are shaped and fitted with utmost precision.”

The car I bought was LML/50/316, with engine number VB6B/50/1144 originally delivered June 17, 1953, by J. S. Inskip in Manhattan, famous as the U.S distributor of Rolls-Royce and coachbuilt cars from Brewster & Co pre-WWII. After the war, they added Bentley, Aston Martin, Riley and MG.

Based on the price, I expected to have a five-year project before I had an Aston Martin sports car. However, the first look, in an old Connecticut barn, was a complete surprise. The paint was cheap and old, but undamaged. The leather interior was complete, but tired. All the instruments worked and the clutch was described as new. The owner climbed in, pushed start and it barked immediately to life. He drove it onto the trailer and I drove it continually through seven years of refurbishment—it was never “restored.”

The three key figures in my Aston Martin education—and parts sources —were Kingsley Riding-Felce, Director of Works Service and Customer Care in the home village of Newport Pagnell, Ken Boyd at Aston Martin Services in Needles, California (NO!! REALLY!), who could overnight virtually any post-war Aston part, and the man who knew as much about Astons as anyone in America, Richard (Dick) Green of California. The beautiful leather that eventually filled the car cost me less than $200 per hide and came from the woman who furnished virtually every hide used in an American car for decades—she had a volume price. The local upholsterer near Ann Arbor said it was the finest leather he had ever handled, “…a rolled up hide would lay over your arm like a roll of silk.” The paint was done by a local “body repair shop” the owner of which was thrilled to be asked to do the project. His assistant block-sanded and primered until it was unlike anything that had ever come out of his shop. He mixed a very dark green to emulate what I described as “British Racing Green.” It was nearly black and looked too hard, but he blended about a tablespoon of ivory per gallon and softened it to perfection.

On the road again, it was seen at car events all over Southern Michigan and drew an invitation to the Eyes on Design show at Edsel Ford’s fabulous Cotswold Mansion. It was never going to be a show car, it was covered with badges and stickers as my sports car would be, but my daughter Tessa, who acted as my co-driver for the Eyes adventure, and I were stopped several times on the show field to hear accolades, something to the effect of, “You have the most authentic car on the field.” As far as I was concerned, I had won. That is exactly what I was trying to build. It was also invited to share a vintage sports car display with Tracy’s Alfa Sprint at the North American International Auto Show in Detroit, but being on the road was its real life.

The Crane family was well known for our car events and the Aston was a popular participant. The first and most popular was our lawn party breakfast on the third Sunday in September. After 12 years it included 240 fascinating people, who happened to arrive in as many as 115 great cars. After the eighth year, one of our guests, a neighbor by the name of Bob Lutz who never missed one, asked if we could organize something that would include his nearby farm—and his beautiful garage and shop full of classic cars. The result was a 100-mile tour of Southern Michigan ending at his farm for chili and beer and Swiss music. We called it “The Casa Crane to Lutz Farm Tour of the Twisty Bits of Four Counties.” We made great memories.

Another was our Michigan Beaujolais Run on the Saturday, after the third Thursday in November, when the Beaujolais Nouveau was released in Lyon, France. We based the idea on a traditional English event that was essentially a race across France to Lyon to collect the young wine and get back to London for a grand French dinner. Our Aston DB2-inspired version was slightly less pretentious. Each entrant got two bottles of the young wine and we set off for a late autumn drive to dinner. On a couple of occasions we made the drive to London, Ontario—emulating the famous run back to London—for an overnight on Richmond Avenue where there were fine restaurants and Cuban cigars. Those trips always included the RM Restorations shop where some really talented guys did fine work before they became RM Auctions and reached a few hundred thousand more customers.

Through all of its official entries the little Aston remained my daily sports car commuter. Just before the wiring harness was ordered, a friend came by for lunch carrying a Ferrari Market Letter, which I had not seen for years. There was 330 GT 2+2, a car I had owned 25 years earlier. My heart rate climbed and the Aston left the building. Never trade a car you enjoy for a car you remember loving 25 years earlier. It is not the same car. The Aston went to a shop near Silverstone, in England, where it was to be recreated as a fast vintage rally car for a German customer—I hope it’s having fun.