1939 2-Liter Monoposto Speed Model

Back in 1966 I bought the second serious car I ever owned, a 1958 Aston Martin DB 2/4 Mk.III—the last production car before the DB4 came along and brought Aston Martin into the modern age. My insurance broker struggled to get coverage for the Aston, there not being many “Austin-Mertons”, as he put it, in Pennsylvania at the time! I hill climbed and auto-crossed it, and I believe it was probably the only Aston ever raced on a dirt track, such were the facilities we had in central Pennsylvannia at the time. At Monaco in 1969, I happened to tell Denis Jenkinson about it while a group of Aston owners were having dinner during Grand Prix week. He approved of it as the last of the “proper pre-war sports cars”, not disguising his preference for older cars and also seeing this David Brown product as still strongly connected to Aston Martin’s pre-war heritage.

Strangely, I don’t think I’ve driven an Aston since, so an invitation to try the very rare beast you see here was quickly and gratefully accepted. I thought my old Aston knowledge would return and I would rapidly be able to place this car amongst the many I used to go see at Aston Martin Owners Club meetings years ago. This was a mistake. This is indeed a unique and little-known car, only recently discovered and restored by Ecurie Bertelli’s Andy Bell. The story was, however, seminal, a quintessential piece of the long Aston Martin competition story.

The 1.5-liter heritage

While Aston Martin, the company, is known almost entirely to the general population as the constructor of luxurious supercars and the builder of exotica for James Bond, this is to miss much about the origins and history of a fascinating car manufacturer.

Photo: Peter Collins

Several other important threads need to be traced back through Aston Martin history: the never-ending involvement in competition from Lionel Martin’s Isotta Fraschini chassis, which became the basis for what is considered the first Aston Martin; right through the DBR9 which recently appeared at the 2005 Sebring 12 Hours. The second thread is the tale of the financial rollercoaster this company often seemed to be riding, which brought in a number of entrepreneurs who brought it back to life and created new initiatives. In the pre-war period particularly, there was the long, but not quite total dependence on 1.5-liter 4-cylinder cars. All of these threads contributed to the existence of the car you see here.

When Lionel Martin’s partnership with Robert Bamford ended in 1922, after nine years, Martin went to work producing a number of racing cars and prototypes, many of which used a 1,486-cc side-valve engine. Single-and double-overhead cam engines were also developed and the first production cars were sold in 1923. The company was refinanced in 1924, production ceased in 1925, the company went into receivership and Lionel Martin left. Interestingly, some of the cars of this period survived and are still found in historic racing. The company was then saved by Augustus Bertelli, already a well-known driver and engineer, who with William Renwick was already producing a 1.5-liter engine for proprietary chassis, so the pair re-founded the company in 1926. A factory was leased at Feltham and various investors were found, but the financial stability remained precarious. Bertelli and Renwick were soon producing a conventional chassis with a 120-in. wheelbase with the axle over the frame, which became a fairly standard layout. A more sporting model soon appeared and this was the first of the international series of 1.5-liter cars. The small factory could produce two/four seater touring bodies or sports bodies, some with three seats, which became the first Le Mans cars, and continue to be known as the LMs. The first series cars, almost all of which had characteristic cycle fenders and an under-slung chassis and a dry sump, were produced from 1927 until 1932.

Photo: Peter Collins

A second series was produced from 1932 until 1933, during which time the company was again refinanced. The quality of the cars, particularly the handling, was very high and this kept a steady, albeit small, stream of customers coming to the door. The Mark II emerged in the third series from 1934–35, and the long chassis model Mk.II became the best of the 1.5-liter cars for touring use, while the short-wheelbase Ulster remains a highly desirable collector’s car. Sir Lancelot Prideaux Brune stepped in to save the company in 1932, but at the end of that year he transferred ownership to Sir Arthur Sutherland, whose son, R. Gordon Sutherland, became joint managing director with Bertelli. Gordon Sutherland was an able engineer and manager, and he led the company to a degree of prosperity in this period, and was fully behind an active racing program as well. Works, or works-supported cars, appeared at Le Mans, the Mille Miglia and Spa, as well as Brooklands, and the value of good results in racing was soon learned.

1935 saw the last full works racing effort until after the war, though there was still much help available for privateers. The 1.5-liter cars were coming to the end of their development, as they were now somewhat heavy and expensive. There were rumors about a bigger engine, and then in 1936, experiments were carried out on a 4-cylinder unit with a bore and stoke of 78 x 102 mm. which gave a capacity of 1,949-cc in a layout similar to the earlier 1.5-liter cars. Two prototypes were built to be used at Le Mans but there was no race in 1936, so the cars were sold but raced with factory support. Two more cars were built, one of which was entered by Richard Seaman for the Tourist Trophy. This car did very well against bigger opposition until the bearings failed. However, Sutherland backed the move to 2-liter production and racing cars. He held back from running works racecars and argued that Aston Martin needed to have a sports saloon as the main, income-earning model. This wisdom probably prevented the company from going out of business. The 2-liter, first referred to as the 15/98, appeared at the October London Motor Show in three guises: a four-door saloon, a two-door four-seater tourer, and the two-seater Speed Model. The Speed Model was essentially a production version of the cars which had raced at the Tourist Trophy. More importantly, the Speed Model maintained Aston Martin’s sporting image.

The Monoposto

Throughout the Sutherland period, Aston Martin was continually involved with experimental work. One result of this was the appearance of a Type-C 2-liter, the first Aston with a more rounded and aerodynamic body shape. This car received mixed reviews amongst those who thought all sports cars should have cycle wings!

Photo: Peter Collins

During 1937, Sutherland met R.C. Cross, who had invented the Cross Rotary Valve. After a number of experiments using a single-valve engine in a motorcycle, Sutherland and Claude Hill went ahead with work on a rotary valve engine as this engine could burn pump fuel at a compression ratio of 11:1. A design was laid down to adapt the rotary valve head to an existing 2-liter Speed Model crankcase and lower assembly. It was a complex design, but was finally completed, though with many teething problems. Longer-term tests, however, were not successful and after a great deal of work, the project was seemingly abandoned. However, Sutherland and Hill had assembled a chassis to try the engine in. Contemporary reports say that Sutherland was going to use the engine and chassis to set a new record at Brooklands, and this belief about the purpose of the car persisted for many years.

When the then–93-year-old Sutherland heard in 1999 that Andy Bell had restored the car, he wrote a detailed letter about the car:

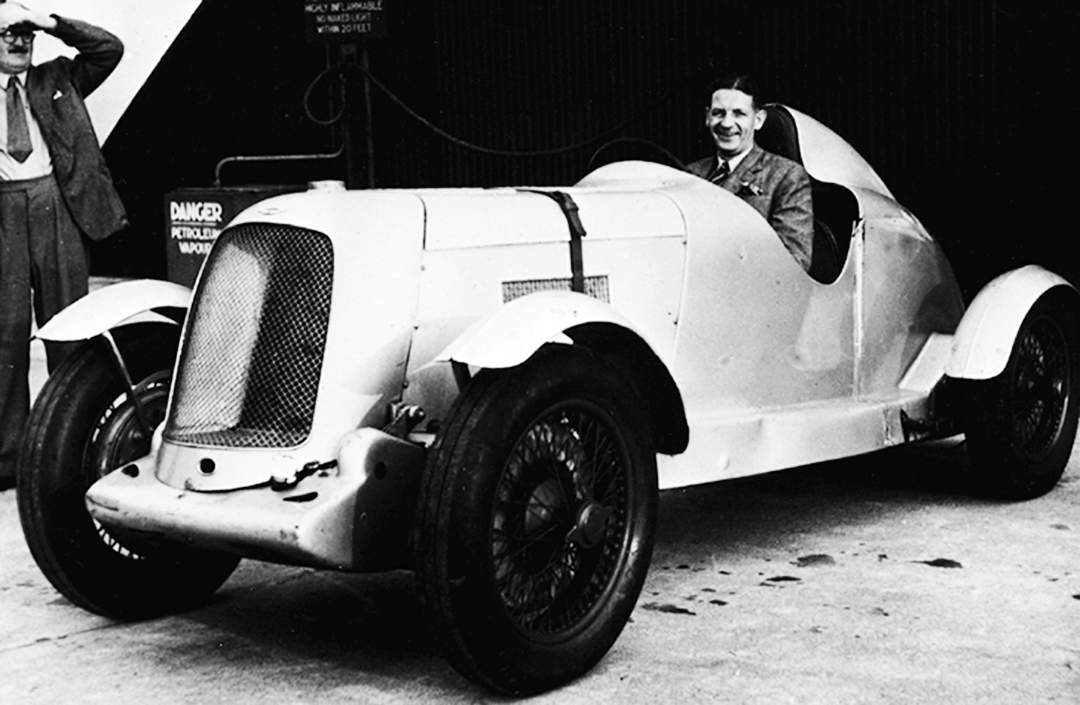

“A great deal of nonsense has been mentioned about this car, even that it was built for an attempt on the Brooklands lap record. The truth is that we wanted to publicize the Cross Rotary Valve on which we had experimented over a year hoping to put new life into the Renwick and Bertelli engines. After much work and a good deal of frustration, we got results about equivalent to the existing 2-liter Speed Model but not the increase that had been expected. To publicize the valve, we got the idea of building a lightweight single-seater racing car to run at Brooklands fitted with Cross valves.

“Although this might have no more power than existing Astons, it would lap faster due to its light weight and streamlining. To do this we eliminated all the electrics: battery, starter, dynamo, fuel pumps, thus saving about 2 cwt. I think the weight was about 16 cwt, about the same as a BMW 328 and the lightest Aston yet built. A mechanical lightweight fuel pump made by Self-Priming Pumps of Slough was fitted and a high axle ratio of 4:1 which gave 60 mph in first gear. We had reduced the track of the chassis to 4ft 2inch and I drove it on the road as a chassis with a bucket seat and no wings and found it most exhilarating getting away from the lights…quite impossible with modern-day traffic regulations!

“We had rather a crude streamlined shell body fitted and I took it to Brooklands to try. It was never registered or painted by Astons. Due to the lightweight and hard springing, I found it almost uncontrollable at speed. Charles Brackenbury, who was also at Brooklands, tried it and said ‘it’s not too bad’ or words to that effect. Anyway, we would obviously have had considerable work to the springing, so it was temporarily put to one side. Then the war intervened as well. Subsequently, we abandoned the Cross Rotary Valve and got paid 5,000 Cross shares for the work we had done. This turned out to be probably the most valuable asset David Brown bought with the company (in 1947). I personally bought some of these shares and since they dropped the Rotary Valve and concentrated on other specialized work for the aircraft industry, they have paid good dividends, even helping to build a new factory. Claude Hill and I continued development on a pushrod engine after Bertelli left in 1937. This proved to be a good thing as indicated by our success at Spa in 1948.”

The Second Incarnation…and Third

Although the timing is not entirely clear, it also seems that after the initial tests with the rotary valve engine, the car was fitted with the 2-liter Speed Model engine which had first powered Seaman’s car at the Tourist Trophy. That engine was taken back to Feltham, while the car went to Dutch driver E. Hertzberger with a replacement engine and raced in the 1937 Mille Miglia. As a result, the Monoposto with the ex-Seaman engine did further testing at Brooklands before the war. As Sutherland states, the Monoposto was based on a lightened Speed Model chassis which was made narrower with reduced front and rear track. It also incorporated an angled steering column. The body was purposeful rather than good-looking, with a sloping cowled radiator grill and a fared headrest. It was a learning exercise for Aston Martin, because this was the first and last single-seater racing car before the war.

In the second series of tests, Sutherland was nearly thrown out on the bumps yet again, and then had failed steering and brakes and was lucky to avoid an accident. The car then saw no action until after the war, by which time David Brown was in charge and he sold it to a garage in Huddersfield for £1,000, and it then went to Knaresbrook coachbuilder Gordon Gartside, possibly for £250. The car had not been registered or had any known chassis number at that time. It was Aston Martin’s practice not to assign a chassis number until a car was sold, and the Monoposto was never sold to a customer in period. However, the engine number was H6/711/U and this has helped to confirm the identity of the car, which Gartside’s driver, John Hallas, has confirmed. Hallas explained that when the ex-Seaman car, now known as Red Dragon, was sold overseas with a different engine with chassis number H6/711/, the customs papers identified it by this number even though the engine had already gone elsewhere. Hallas also confirmed that the Monoposto had actually raced once at Brooklands before the war.

Gartside had the car re-bodied as a two-seater, with quickly detaching wings and a new radiator cowl with plated grill. It had a much lower bonnet with a special bulge for the carburetor. The tail was long and tapered downwards, and from some photos it appears possible that it had two different tails used while Gartside had it. It did a number of races in 1951 but Gartside found that the body did not conform to international sports car rules, so he built a third body. It raced as the Gartside Special in 1952 and 1953, particularly at Silverstone but also at Croft, often with John Hallas driving, but did not contest any international events. When Gartside sold the car to George Longdon it had a different engine, a rare DB1 2-liter unit. The Seaman engine then powered another vintage Aston before being reunited with the car as it is now. In the meantime, the car had disappeared in Yorkshire only to be discovered more than 20 years later by ex-Aston mechanic Bill Smith, who rebuilt the car for a Harrowgate dentist, Dr. Uberg. Ecurie Bertelli’s Andy Bell was trying to sell the car for Uberg but was so smitten by it himself that he eventually bought it, having made the brave decision to convert it back to its single-seater Monoposto form.

Thus the car is now in its fourth and final(?) incarnation. The body is a synthesis of the car’s history rather than a copy of any of the specific bodies. This was to make it a more manageable and tractable car while retaining the core of the original spirit, and these aims have clearly been achieved.

Driving Aston History…the Fourth Incarnation

It seemed immensely fitting to be introduced to this car at no less illustrious a location than in front of the Aston Martin offices and factory at Newport Pagnell, where the works moved to after leaving Feltham. Even the son of the late Victor Gauntlett, one of the post-war entrepreneurs who ran Aston Martin, came over to say hello and look at this piece of history lined up next to a brand new DB9.

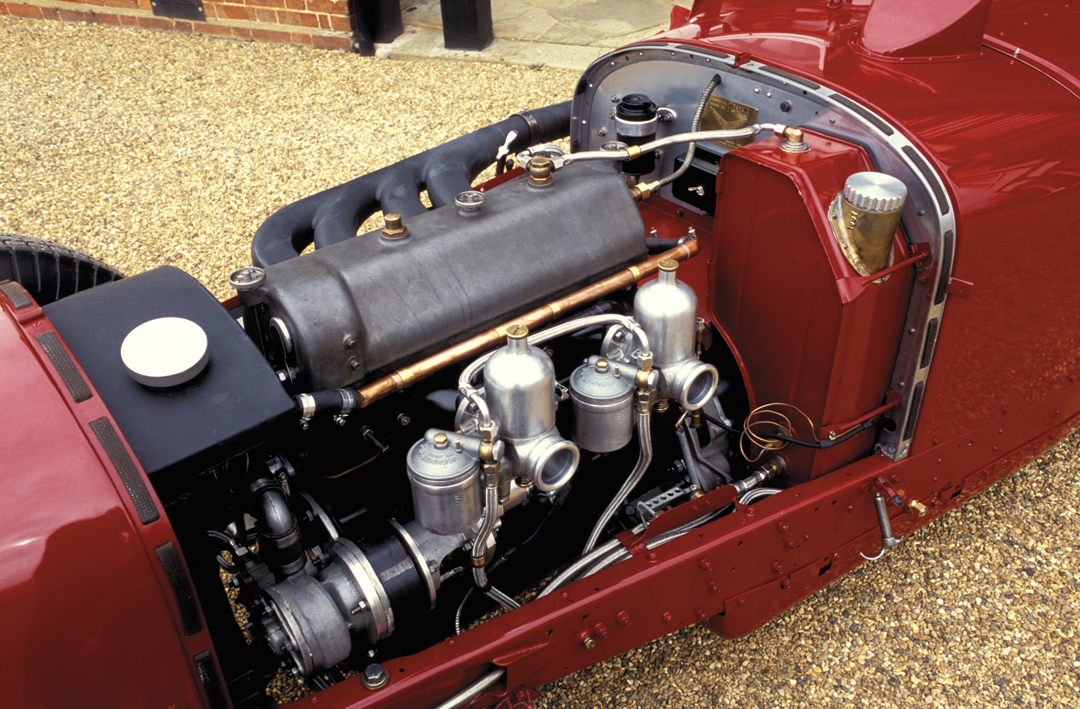

After getting round the first obvious difficulty of getting into the car due to the low angle of the steering wheel, its size and the lack of a second or third joint in my leg, it was business as usual, though there was little usual about this car. Though the Monoposto appears very similar to many pre-war two-seaters from the outside, it’s quite different in the cockpit. The seat holds you snugly in single-seater fashion, a good thing as the drivetrain runs right alongside your hip. There is a fuel pump where a passenger would formerly have sat on the left, so it’s reasonably comfortable, with plenty of room for your arms as they whip round the large steering wheel.

A sizeable Jaeger rev counter, reading up to 8,000 rpm, is the dominant instrument, with fuel and ignition switches under the metal tonneau cover on the dash, and the usual temperature gauges. The gearbox is a four-speed in a standard H-pattern, but with quite a high first-gear ratio. We transported the car to a local and somewhat-deserted country park for the driving part of this test, and I had a real workout managing the central throttle, the high first gear, and an engine that threatened to die if you let the revs drop. All of this was compounded by the presence of speed bumps…and guess what, it seemed that Gordon Sutherland’s hard springing was still there!

The exhaust runs down the right-hand side, but fortunately is covered to protect the driver and others, though it gets noticeably warm. The temperature is forgotten once the 4-cylinder unit warms up…the very engine that pulled the great Dick Seaman around the rapid Tourist Trophy circuit back in 1936. There are a number of interesting touches…fared in mirrors on the dash and a tidy and functional aero screen. The view from the cockpit transports you across the decades with all those louvers and exposed wheels and large drum brakes…things you can watch bounce around as you drive. There are two period fuel filler caps behind the driver, further signs that this is definitely a racing car. It would seem possible to remove the tonneau cover for a passenger, but it would take away from the distinctive body shape that Andy Bell has achieved…and after all, this was a single-seater.

Driving is one of those “moorish” experiences…or is it “more-ish”…you just want to keep going. The engine barks through the exhaust and even with a high first gear the torque is evident and usable, the car just blasts away from the line. Once the location and feel of the gears are established, the box is a treat, up and down with no trouble, and the brakes are totally efficient. Once I manage to dodge the bumps, the handling comes into its own, and the circuit-racer nature is fully revealed. Andy plans to race the car this year and who blames him? It’s an exceptionally responsive package, never mind the history. The grip is superb on Blockley Tyres’s 5.50-18 Cross Ply on the front and rear. Though this is a unique car, it shares much of what period drivers loved about the LMs, the Ulsters and the Speed Models, especially in long distance-events. Some of the best performances, if not always results, came at Le Mans, Spa and the Mille Miglia, and even the Nürburgring. It’s a car that a driver gets comfortable in, it fits around you, it responds to what you want it to do. Combine that with superb road holding, even in the wet, and it is a real racer’s machine.

Buying and Owning a Pre-War Aston Martin

There are pre-war Aston Martins on the market…even as we speak. There’s a 1929 Brooklands Double 12 car, LM3/129R, one of seven international works team cars, a 1932 Standard Four-Seat Tourer, a 1939 2-liter Saloon and a 1924 Bamford and Martin Short-chassis Tourer, amongst others. These range in price from $70,000 to $120,000. Of course, cars for restoration are also out there, but I think it would take a brave person to take on restoration of one of these cars without good backup.

When it comes to the Monoposto…well, here is a car that once changed hands for £1,000 and then again for £250, and more recently for a lot more. What’s it worth now? I think the question is academic as Andy Bell isn’t going to part with it, but the Astons with significant history will get a substantial price. A standard speed model will be valued around $300,000 and this one near $350,000. Once up and running, they are relatively painless cars to look after, but they do like to be driven. Many UK owners also race them, as they do in the USA, and that changes the complexion when it comes to maintenance and cost. Engine parts are now available, fortunately, and a number of efforts have ensured a supply of blocks for many pre-war Aston Martin models.

When you drive a 66-year-old car, there’s a part of you that inevitably wants to preserve and baby it. But once the throttle is down, this is a car to race. How you expect to treat a car like this is the key ingredient to how much it’s going to cost you.

Specifications

Model: 2-Liter Speed Monoposto

Suspension: Adjustable friction shock absorbers front and rear

Wheelbase: 8ft 3inch

Track: 4 ft (approx.)

Engine capacity: 1,949 cc

Power: 150 bhp @5,000 rpm (approx.)

Compression ratio: 8.3:1

Bore and stroke: 78 x 102 mm

Lubrication: Dry sump

Brakes: Girling hydraulic brakes, pedal operating two master cylinders in tandem

Gearbox: 4-speed and reverse, synchromesh on second, third, fourth; in unit with engine

Clutch: Borg and Beck

Wheels: Knock-off wire wheels, 18 x 5.25 in period, currently with Blockley Tyres-5.50-18

Top speed: 120 mph

Resources

Thanks to Andy Bell and Ecurie Bertelli for the use of the Monoposto. (www.ecuriebertelli.com).

Coram, D. “Aston Martin-The Story of a Sports Car.” Motor Racing Publications, London 1966.