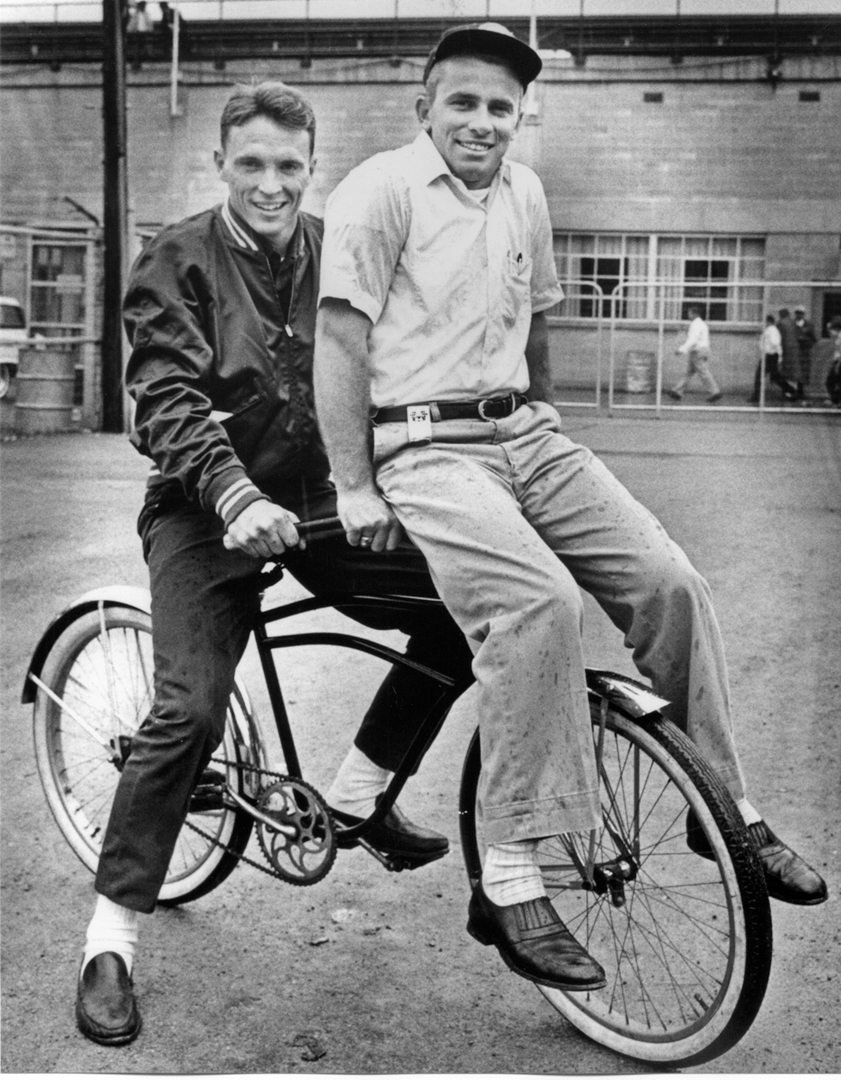

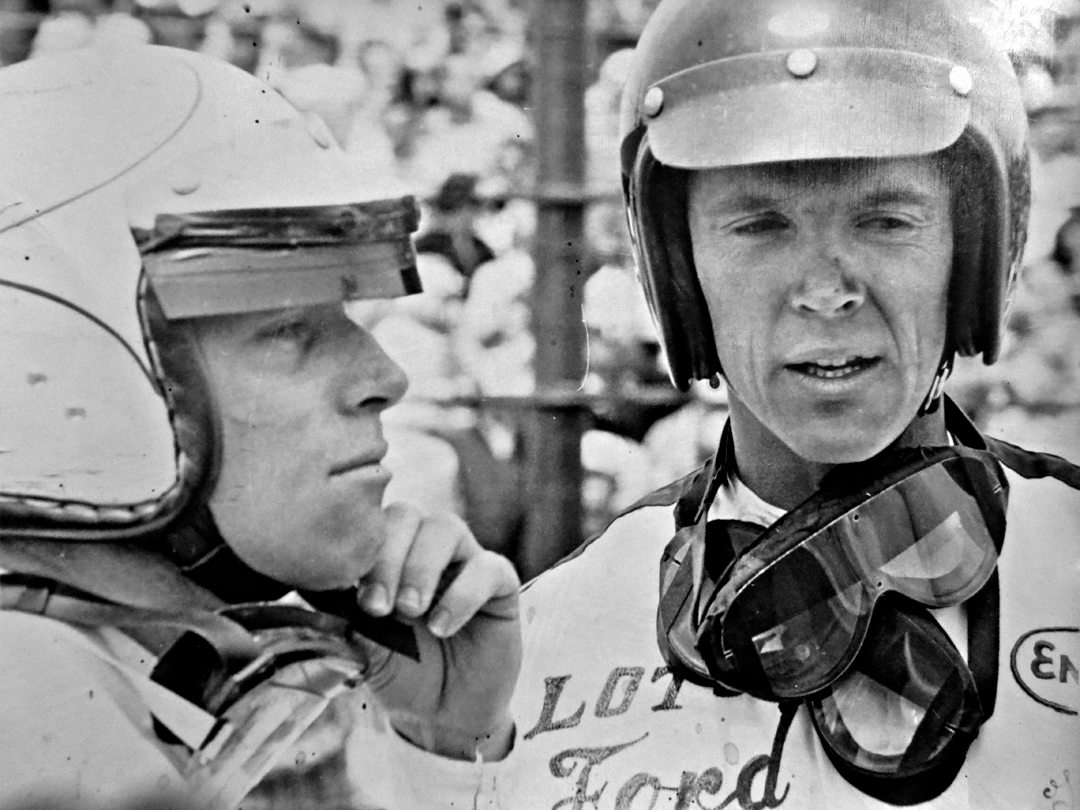

Many were the similarities shared by young American racer Bobby Marshman and the Scottish Legend

Colin Chapman called Bobby Marshman the American Jim Clark, and it is difficult to imagine a higher compliment. The two men shared many common characteristics as both were relatively slight of build and mild of manner, both were articulate and analytical, both harbored a touch of mystery behind their bright smiles and mischievous eyes, and both were undeniably quick in a racing car.

They competed against each other only four times, and it was the last of these, the 1964 Indianapolis 500, where Marshman validated the comparisons to the reigning World Champion.

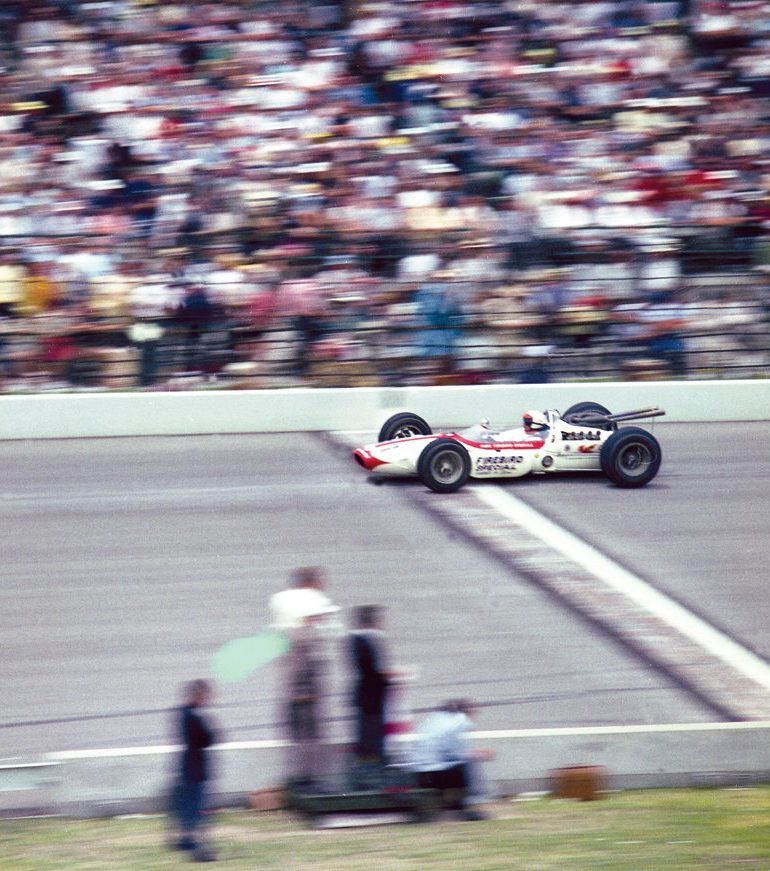

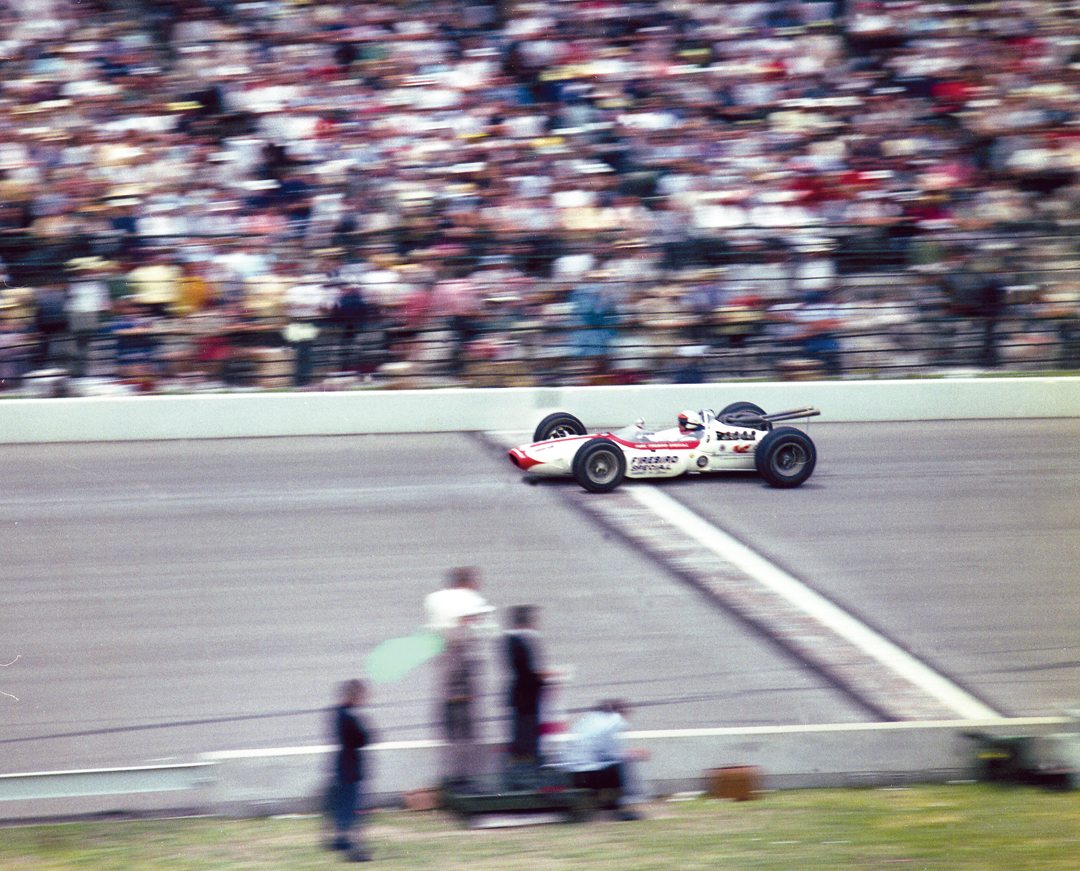

Driving Lindsey Hopkins’ Pure Firebird Special, one of the previous year’s Lotus 29s updated with one of Ford’s new DOHC Indy V8s, Marshman ran at or near the top of the speed charts most of the month that May. He then set a new track record of 157.867 mph in qualifying, and though it was subsequently eclipsed by Clark’s 158.858 mph pole run in the current Lotus 34, Bobby still started the race from the middle of the front row. On race day, once Benson Ford pulled the Mustang Pace Car into the pits, Clark led Marshman and the rest of the 33-car field briskly away from the start before the unprecedented second-lap red flag for the dreadful Dave MacDonald-Eddie Sachs crash.

Photo: IMS

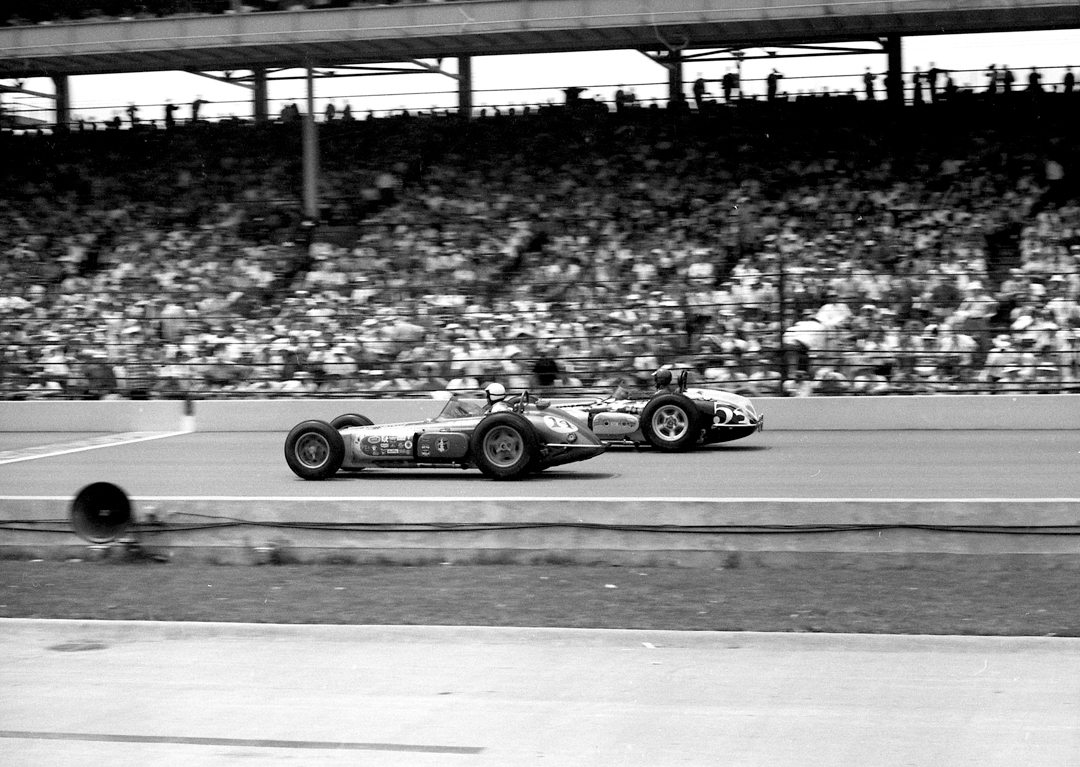

Once the race was restarted Jimmy and Bobby ran away again, but behind them the clouds of oil dry and extinguishant kicked up by the field as it filed through the crash site caused some drivers to slow considerably. Consequently, lapping started earlier than usual, and when Clark came up to lap Bob Harkey’s Weir-Mobilgas Watson-Offy roadster into Turn 2, on the seventh lap, he intended to go around on the high side. Harkey, however, drifted up, balking the Scot and opening the door for Marshman.

Nipping low onto the flat “apron” ringing the inside of the nine-degree-banked oval, Bobby slipped past them both and into the lead, then began to pull away. Regularly logging new race lap records—his 15th lap was his best, at 157.646—he deftly knifed through the traffic more comfortably than Clark so that by the 30th circuit he enjoyed half a lap’s advantage. The Hopkins team’s crew chief, Jack Beckley, knowing that many miles remained to be run, tried to rein him in by holding up the pit board imploring him to “Cool It.”

Into Turn 1 on his 39th lap, however, Marshman encountered Harkey again, but this time as he went down below the white line onto the apron in the South Short Chute to lap the blue car, the Lotus bottomed out on the uneven asphalt. Prior to the race Beckley had rearranged the car’s oil delivery system so that instead of tucking into its original groove in the underside of the chassis, the pipe from the auxiliary tank was repositioned, according to former Lotus competitions manager Andrew Ferguson in his book Team Lotus: The Indianapolis Years, “outside the tub’s left-hand curvature, vulnerably close to the track.” Both the relocated pipe and the engine’s sump plug were damaged when the car hit bottom on the apron.

Chased by an ominous mist of oily vapor, the crippled white car went around one more time before Bobby pulled off onto the grass inside the North Turn, climbed out, scaled the fence and began walking back to the pits.

With Marshman out, Clark reassumed the lead, but his day was doomed as well. Lotus boss Chapman had chosen softer Dunlop tires instead of the prevalent Firestones for his two cars, and when they began to delaminate the subsequent dynamic imbalance set up a nasty vibration. As Clark sped down the main straight on Lap 47 the green car’s fragile left rear suspension collapsed, folding the wheel and tire assembly over onto its tail and leaving Jimmy to dazzle the fans in the stands with his control of the three-wheeled machine as he headed for the grass inside the first turn to retire. Dan Gurney’s similar team car was soon called in to be withdrawn as well.

A.J. Foyt, of course, went on to win that race—the last victory for a front-engined car at Indy—while Bob Harkey soldiered on to finish a fine 8th, three laps behind.

Making His Mark

Bobby Marshman had first raced at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway three years before, in 1961. That year’s 500 was a landmark event for more than one reason. Chronologically, it marked the 50th Anniversary of the first 500 in 1911. Technically, it was the dawn of the modern rear-engined revolution at Indy as the reigning Formula One World Champions, driver Jack Brabham and constructor John Cooper, entered a modified Grand Prix Cooper-Climax to challenge Indy’s standard Offenhauser-powered roadsters. Institutionally, a new concrete and steel grandstand lined the outside of the main straightaway, replacing the previous wooden structure, and, retrospectively, it produced the first of the four victories that would earn Anthony Joseph Foyt Jr. legendary enshrinement at the facility.

Foyt’s first 500 win came after a fierce late-race duel with Eddie Sachs that was ultimately decided by an error in the Texan’s pits that sent him out less than fully fueled and led Sachs to wear out his tires in his efforts to keep up with Foyt’s accidentally lighter car. In their wake were two performances that also merited significant attention as a pair of young sprint car stars made their debut appearances at the big old Speedway.

The first of these was 27-year-old Arkansas-born Californian Parnelli Jones, who qualified J.C. Agajanian’s Willard Battery-sponsored Watson-Offy 5th and led 27 laps in the early going before being hit in the face with a shard of metallic debris kicked up by another car that split open his eyebrow and began filling his goggles with blood. That, coupled with a pair of fouled spark plug replacements for a bad cylinder, delayed him sufficiently to cost him eight laps and leave him only 12th at the finish. Still, the effort earned him co-Rookie of the Year honors.

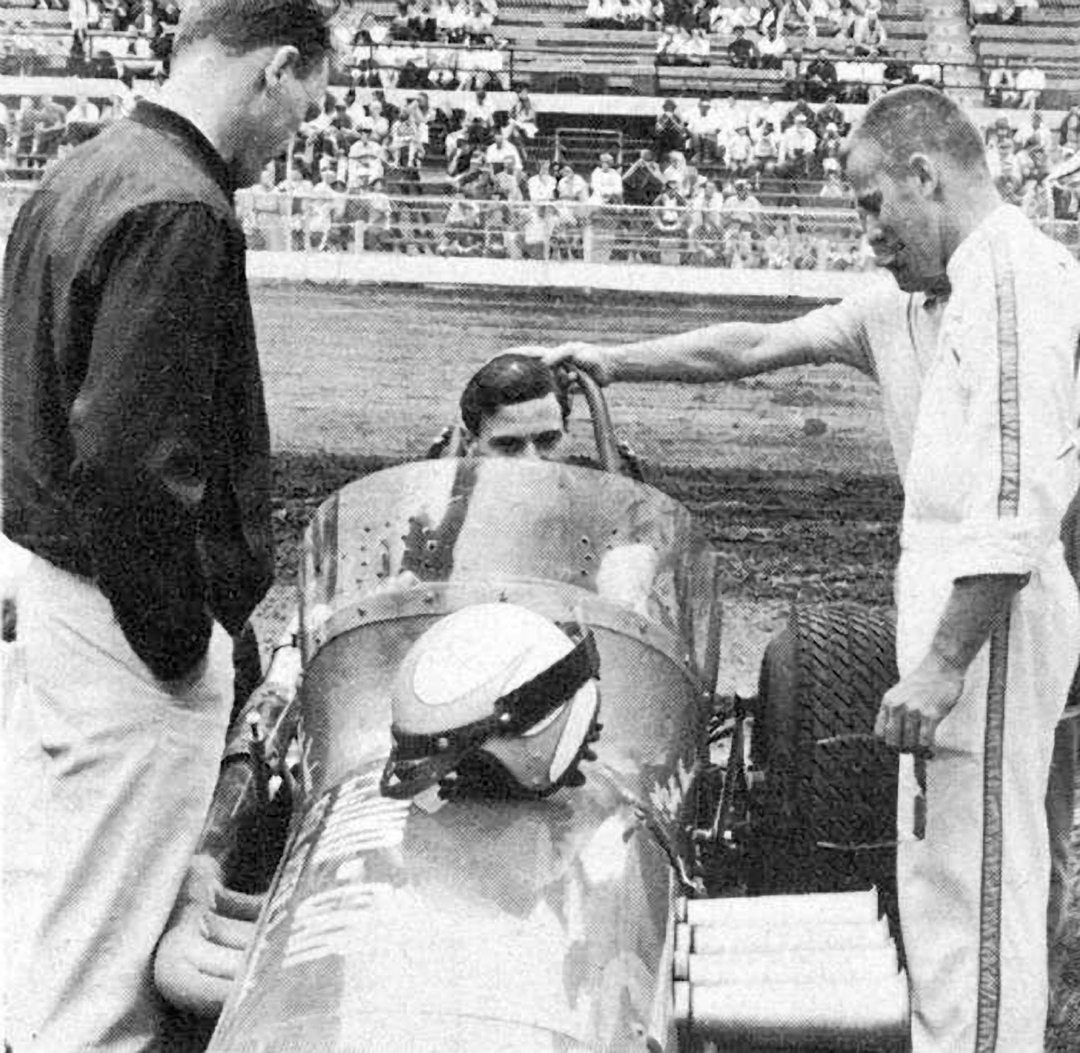

Photo: IMS

That designation was shared with the 24-year-old Marshman, who had come to Indy from Pennsylvania that May seeking a ride, only to head home early when he found no one who seemed interested. Then he got a call from car owner John Wills, beckoning him back to drive the Hoover Motor Express Epperly-Offy, which Bobby scraped into the field in the 33rd and last position, then took up to 7th by the finish.

“He was a young up and coming driver from the East Coast, when I first ran across him in a midget or a sprint car,” remembers Jones. “He turned out to be a good race driver. He had a lot of talent and a lot of desire to win, and made a big hit when he came to Indianapolis because he was such a clean-cut guy who was a helluva race driver.”

Indy ’61 was only the second Big Car start for Marshman, who had grown up with a race-promoting father, George, and first drove a midget at age 11. Until he was actually old enough to race it himself, however, he prepared it for other drivers, but once he got behind the wheel he quickly began making a name for himself on the ovals of the eastern USA. He raced Midgets and Sprint Cars with the United Racing Club, the American Race Drivers Club and the United States Auto Club, USAC, which also sanctioned Indianapolis and the National Championship Trail. His first big splash came in 1960 when he won a 300-mile ARDC midget race on the Mile at Trenton, New Jersey, averaging just under 100 mph in stifling heat.

His impressive rookie drive at Indy—even though he complained he didn’t pass anyone all day, just watched them fall out ahead of him—led veteran mechanic and car builder Wally Meskowski to hire Marshman for the season. Bobby rewarded him with a fine drive to 2nd place in the Hoosier Hundred at the Indiana State Fairgrounds, then took 3rd in the 100-miler at Sacramento in October. Ranked 8th in championship points at year’s end, he was named the series’ Rookie of the Year.

Among the friends Marshman made during that rookie year at Indianapolis was the track’s longtime Media Center manager Bill York. “Bobby and I really became very close friends,” remembers York. “We called him ‘Shoe,’ and that was his nickname for a while. He used to stay at my house when he was racing in May, and park his racecar in my garage. We liked to go out to the clubs and dance the Twist, Bobby and myself, and sometimes Parnelli. Neither of us was a big drinker, we were not into booze, we were just out having a good time—but never anything that got us in trouble.”

Marshman’s 1962 Indycar season opened at Trenton where he qualified and finished 10th in Meskowski’s car before heading to Indianapolis. There he put the Bryant Heating and Cooling Epperly-Offy on the outside of the front row—with the 150 mph barrier-smashing Jones on the pole—and again drove a heady race to roll under the checkered flag in an excellent 5th place.

By midseason, though, the earth was shaking in the paddock as a festering feud between Foyt and his crew chief, George Bignotti, led to A.J. leaving Bignotti’s Bowes Seal Fast team to drive for veteran car owner Lindsey Hopkins. Bignotti and sponsor Bob Bowes then sold their operation to William Ansted and Shirley Murphy, who retained George as crew chief and renamed the cars Thompson Rotary Specials.

Bignotti offered the empty seat to Marshman for the next race, mid-August’s 100-lapper on the Illinois State Fairgrounds dirt mile in Springfield, and Bobby validated his choice by bringing the car to the finish 4th. The next day, at Milwaukee, he sat the team’s Trevis roadster on the pole and finished 3rd to solidify his standing, then followed up with another 3rd in Trenton’s rain-shortened September race.

By then, however, Foyt and Bignotti had kissed and made up, so that a “trade” was engineered returning Foyt to Bignotti’s cars and sliding Marshman into the vacated Hopkins seat. Again Bobby made the most of the move, scoring his first Indycar victory in the season finale on the dirt mile in Phoenix, a race shortened to the minimum 51 laps by a red flag after Elmer George flipped his H.O.W. Special into the grandstands. The win lifted Marshman to 5th in the final USAC points.

Although settled comfortably into Hopkins’ blue-with-orange-trim Econo Car Rental Specials for 1963, Marshman’s expectations went mostly unmet as mechanical failures plagued the team. A prime example came at Indy where he was running 5th with four laps to go when his car’s differential broke and left him to be classified 16th behind winner Jones. However, because Lindsey Hopkins had given advice and assistance to Ford in the early stages of its Indy program, his team and driver were selected to perform invaluable testing and development work for Ford’s forthcoming double-overhead-camshaft Indy V8 that would replace the production-based pushrod engines used by Clark and Gurney in ’63.

Bobby had decided he needed to join the rear-engined revolution after watching Clark and Gurney in the new Lotuses, so Hopkins’ move was perfectly timed. For crew chief Beckley and the team it was a golden opportunity to expand from their front-engined framework and familiarize themselves with the new technologies that heralded the future.

Clark had finished 2nd to the victorious Jones in that rookie attempt at Indy, then came back across The Pond in August to score the first Indycar win for a rear-engined machine at Milwaukee—a day after he and Gurney had sampled the cockpit of Marshman’s dirt car in the pits at Springfield.

Gurney remembers Marshman as, “an up and coming young driver who was doing a lot of testing for Ford Motor Company. It wasn’t long before he was turning lap record times at various tracks around the country—according to the grapevine. He was very likable, hungry and very talented, and there was no doubt he would soon give A.J., Parnelli, Branson and the other top drivers of the time a run for their money.”

Bobby’s only bright spots in ’63 came on the dirt, first at Langhorne where he led 36 laps while finishing 5th, then Springfield where, suitably inspired, he led most of the first half of the race before his magneto failed, and finally DuQuoin, where he qualified 8th and took the checker 4th. Because he finished just four of his 11 starts, however, Marshman ended up only 15th in the final points.

Racing into the Future

The 1964 campaign promised to be better. For starters, as part of the test program, Hopkins had acquired one of the ex-works Lotus 29s, fitted with Ford’s new four-cam V8 and, as noted above, Marshman put it to good use. The performance at Indy convinced Chapman to include Bobby in Lotus’ future U.S. plans, and even ponder giving the American a shot in Europe.

The weekend after Indy everyone reassembled in Milwaukee, but Marshman crashed the Lotus in practice and had to take over teammate Bob Veith’s laydown roadster for the Rex Mays 100. The car lasted only 20 laps before its Offenhauser engine failed.

Back on the dirt at Langhorne—for what would be the last National Championship race on the daunting Big Left Turn—Bobby got back in the groove, bringing the Hopkins Kuzma-Offy home 3rd behind Foyt and Don Branson in Bob Wilke’s Wynn’s Friction Proofing Watson-Offy. This was, of course, the year that Foyt won the season’s first seven races and 10 of 13 overall, and though Hopkins’ Pure Firebird Lotus proved fragile and unreliable in the pavement races—for example, Marshman was running away with the Trenton 150 until a radius rod broke—on the dirt Bobby was A.J.’s closest challenger.

At Springfield he qualified 2nd to Rodger Ward’s Leader Card Watson and jumped immediately into the lead as the green flag waved. He led the first half of the race—Foyt had started 16th after engine trouble in qualifying—but wore out his right rear tire doing so, and was forced to pit to replace it. Rejoining in 2nd, he dogged Foyt to the finish in a classic high-groove-low-line duel, but could not get by.

The next day, following the overnight drive up to Milwaukee, Bobby qualified his Lotus 7th and charged up to pass leader Jones—by then in a Lotus of his own—and hold the top spot for five laps before his engine blew. Jones drove on to win.

Returning to the dirt again, Marshman ran 2nd to the dominant Foyt at DuQuoin, the only other driver on the lead lap. For the Hoosier Hundred—postponed a week by rain—Bobby qualified 2nd then jumped poleman Foyt at the green and led the first six laps before A.J. worked his way by. Just short of mid-distance, however, the rough track surface broke the Hopkins machine’s torsion bar, ending its day. When Len Sutton pitted shortly thereafter complaining that his face was being pounded by chunks of flying dirt, Bobby jumped into the cockpit of Sutton’s Enterprise Machine #27 and took it to the finish in 8th.

The very next day, due to the Hoosier Hundred postponement, everyone headed back to Trenton for the third time that year. Bobby qualified the Lotus 3rd but was stopped just past half distance by ignition failure. He ran 2nd to Foyt again in Sacramento, the fifth of five top-five finishes that would help him finish 7th in the points. All was looking good for 1965 as they headed for Phoenix to close out the season.

Photo: Z Collection

It had been a year in which Bobby had extended his reach by acclimating readily to the still-new rear-engine Indycar technology, as well as landing a stock car ride with Holman-Moody for NASCAR’s Daytona 500 through his Ford connections. He dropped out early at Daytona with overheating, but followed up with a dozen USAC stock car starts that summer for Bill Trainor’s Milwaukee-based Zecol-Lubaid Ford team, culminating with victory in the 100-lapper on the Springfield Mile.

Back in Indycars for the Phoenix season finale, Bobby qualified only 10th, but by three-quarters distance had worked his way up to challenge Lloyd Ruby for the lead. Then a suspension wishbone collapsed, and his season ended in a trail of sparks along the backstretch as Ruby rolled on to the win in Bill Forbes’ Halibrand-Offy.

The Hopkins team stayed on at Phoenix after the race to do more testing for Ford, but it all went wrong the following Friday when Marshman’s car veered hard into the outside railing in the Dogleg, erupting into a gasoline inferno. Bobby was extricated from the flaming wreckage fairly quickly, but not before his body had been badly burned. He was immediately airlifted to the state-of–the-art Brooke Army Hospital burn facility in San Antonio, Texas, for treatment, but died six days later. He had just turned 28, and left behind his wife Janet and their six-year-old son Robbie.

Photo: Z Collection

Clark would return to Indy in 1965 to write 500 history in the Lotus 38-Ford with the first win for a rear-engined car, then filled out his year chasing his second World Championship in Chapman’s Lotus 33-Climax. Had he not skipped Monaco to run at Indy, the Scot might have won the year’s first seven GPs, but his six wins were quite enough to secure his second F1 crown. Clark nearly won the ’66 500 despite spinning twice, but ’67 was a disaster as the team arrived unprepared. He was scheduled to drive one of the revolutionary Lotus 56 turbines in 1968, but then he went to Hockenheim in Germany for a Formula Two race and his own rendezvous with destiny.

Both Bobby Marshman and Jim Clark died in accidents outside their normal spheres of endeavor, leaving us to marvel at what they actually did accomplish, while taking comfort from the thought that they were simply following their shared mission in life: to go as fast as they possibly could.