Photo: Mike Jiggle

Examining the Leyton House CG901 it is as much about the man who designed the car, Adrian Newey, as the car itself. It was Irish novelist James Joyce who said, “A man of genius makes no mistakes; his errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.” Despite Joyce’s quote, it is not always the genius, or the step toward genius that others appreciate or perceive. It will therefore be no surprise to understand that Newey, on his road to ultimate success, encountered troubles along the way. Indeed, this very car cost him his job at Leyton House.

March, the brainchild of Messrs. Mosley, Rees, Coaker and Herd, hit the Grand Prix scene in 1970 with a number of their 701 cars on the grid, entered in the form of works, semi-works and private entrants. Designed by Robin Herd and Peter Wright, the car took advantage of the reliable combination of the Cosworth DFV engine for power and the Hewland gearbox for transmission. In fact, the whole car wasn’t designed to be radical, but more of a “work horse” suitable for customers to purchase to enter the world of Formula One, not forgetting that the era of sponsorship was still a very new concept and therefore financial opportunities were aplenty.

From this initial start, March continued in an unsuccessful vein in Grand Prix racing through to 1977. Their last hurrah was the announcement of the March 2-4-0 (profiled in the November 2012 issue of VR).

Astonishingly, that car never competed in a round of the F1 World Championship, but it made March money from royalties paid by Scalextric—it was one of their best-selling models! March had spread their wings far and wide in the motor racing world and went on to enjoy great success in Formula Two, Indycars, Sportscars and F3000 to mention a few, but it became clear F1 wasn’t for them.

Leyton House March racing team

Photo: Mike Jiggle

Of course, as in most things “never say, never again.” One of March’s most successful F3000 customers was Genoa Racing and their star driver, Ivan Capelli, who won the 1986 F3000 Championship. A chance meeting occurred between Capelli, Cesare Gariboldi (Genoa Racing’s team manager) and Korea born businessman Akira Akagi, whose father made his fortune in the Japanese property market with his Leyton House Company. At that time, Akira Akagi had taken the Leyton House Company to new heights diversifying into all sorts of business and making it one of Japan’s largest conglomerates. Akagi had dipped his toe into the motor racing world previously, but unfortunately his rising Japanese star, Akira Hagiwara, had been killed at the wheel of his Group A Leyton House Mercedes 190E while testing earlier in 1986. The synergy between the camps, Genoa Racing and Leyton House, was that Capelli and Cesare Gariboldi wanted to step up to Formula One and Akagi wanted the world to be aware of his massive corporation. March, with their understanding of building racing cars was the technical link in the chain. So, ten years after March had bowed out of motor racing’s pinnacle championship, they were back with a one-car team. The March 871 car was a compromise car between Andy Brown’s F3000 chassis and Gordon Coppuck’s thoughts for an F1 car of the period. Capelli shone with great results in Monaco, Austria and Portugal, albeit with a normally aspirated Cosworth DFZ engine against the more powerful turbo cars.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

However, the F1 racing scene had moved forward at some pace since March were initially involved. To cope with new trains of thought they were desperate to re-sign their successful young racecar designer, Adrian Newey. He was, at the time, Mario Andretti’s engineer at the Newman/Haas Indycar team. Newey, a new breed of engineer with his roots in aeronautics and aerospace, returned mid-1987 after contractual obligations were satisfied. Given his background, the 881 would be possibly one of the most revolutionary March F1 cars ever to hit the track. A very compact car now powered by a Judd V8 atmospheric engine was produced. With low drag and high downforce features it didn’t disappoint with Capelli’s best results, 3rd in Belgium and 2nd in Portugal, helping him to 7th place in the drivers championship—he even led the Japanese GP, overtaking Alain Prost’s McLaren, the first time a non-turbo car had led a race for four seasons. He had been joined in the team by Brazilian Mauricio Gugelmin, who had previously been overlooked by Lotus a couple of years before—they favored Johnny Dumfries. It was Gugelmin’s car that seemed dogged with problems in the early races, mainly caused by a faulty batch of crown wheels and pinions. The car was very rigid, but more driver friendly on long flowing circuits as opposed to tighter, twistier venues.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

It had been a great season for this small fledgling team finishing 6th in the Constructors Championship and was a great springboard looking forward—building upon success is the name of the game in all forms of motor sport, especially F1—but it wasn’t to be. Disaster struck with the untimely death of Cesare Gariboldi in a car accident at the end of 1988, a devastating blow. The March Group Plc. was in financial turmoil too; sponsor Akagi having to inject a financial stake in the company to aid survival. Falling into the trap of majoring on the F1 project and taking their eye off of valued customers in other forms of the sport was about to cost March very dear.

On the car front, Adrian Newey wanted to push the envelope of compactness even further, commissioning a slim-line Judd V8 to assist his cause. The new CG891 (CG in deference to the late Cesare Gariboldi) was a little late in appearing and didn’t turn a wheel at a Grand Prix weekend until the third race of the season, at the principality of Monaco. A very poor season, however, with a series of retirements, was in store. Capelli’s best result was 12th at Spa. Gugelmin fared a little better with 7th places at Spa, Suzuka and Adelaide and a 10th place at Estoril. This poor form let the team slump to 12th place in the Constructors Championship. Fortunately, Gugelmin had finished the first race of the season, the Brazilian GP, in 3rd place in an upgraded 1988 car to earn valuable cash-paying points.

Photo: Maureen Magee

March becomes Leyton House and produces CG901

The end of the 1989 season brought a major development in the ownership of the F1 team. Robin Herd resigned as Chairman of March, as the company faced liquidation. John Cowan, who had taken over the reins, decided there was no point in continuing in F1; March had been strong in the past supplying customer cars, and in his mind that’s where the company’s future lay. Obviously, now in the top flight of motor racing, shareholder and major sponsor Akagi wanted to stay in F1 and had the financial clout to do so. He cashed in his stake in March and purchased the Grand Prix team. It would now race under the banner of Leyton House F1 from the 1990 season onward. The new Leyton House team had purchased the entire facilities of March F1, including the wind tunnel and both fabrication and design suites. In fact, the new Leyton House team, based in Bicester, England, with regard to resources, was now on a par with some of the front-running teams on the grid.

With a firm and stable financial footing there should have been no problem ramping up the ante with the new car—CG901. The car was an evolution of the CG891, some say a very bold move by Newey given the disastrous year the team had had. It was possibly the most extreme aero car on the grid. Basically, the construction of the car is a “tub,” or monocoque, made of carbon fiber. This tub is the envelope housing the fuel cell, cockpit and dampers for the front suspension. As with most Newey-designed cars, the driver is secondary to the demands of a significant aero package, leaving a very small cockpit. It snuggly accommodates the driver, but leaves minimal room for maneuvering. Small bulges in the flanks of the chassis accommodated the drivers’ heels. Regular bouts of fatigue by cramp hit drivers, their discomfort inadvertently leading them to use the clutch pedal as a footrest. It is said, even though both Capelli and Gugelmin were of relatively diminutive stature, on occasions, they had to be helped from the car after races.

Photo: Paul Kooyman

As with most modern F1 cars, while there is an overall technical director orchestrating all the packages, there are others who have particular design briefs, and this was so with the CG901. Adrian Newey, as technical director, was responsible for the car as a whole, but Andy Brown majored on the suspension set up with Gustav Brunner. The car was designed with a very high rising-rate suspension, looking at the car from the front, it’s easy to see the “ears” protruding from the monocoque. Following a design miscalculation at the point where the top of the rocker and pushrod connect, cut outs at the top of these “ears” were necessary to accommodate this. These were distinctly different from the CG891, which had much smaller bulges in that area.

Driver aids including active suspension and platform control were technologies being increasingly looked at and researched in F1 at this time. Newey’s radical aero package was all well and good, but as the car pitched and rolled with uneven track surfaces these aero advances might have been negated. What was needed was a stable environment for the car to behave as it had done in the wind tunnel to give optimum aero results. Active suspension, had already been developed successfully at Lotus, as evidenced by Ayrton Senna winning the 1987 Monaco GP.

Photo: Maureen Magee

Indeed, March had produced an “active” version of the CG891. Bruno Giacomelli, who test drove the active car told VR, “I was in charge of testing and developing the active car. It was a shame money became a problem because it was far quicker through corners than the new CG901. In the end, the team said they just couldn’t afford it and the system was dropped.” Had they continued, perhaps Leyton House would have had a very different car than they ended up with?

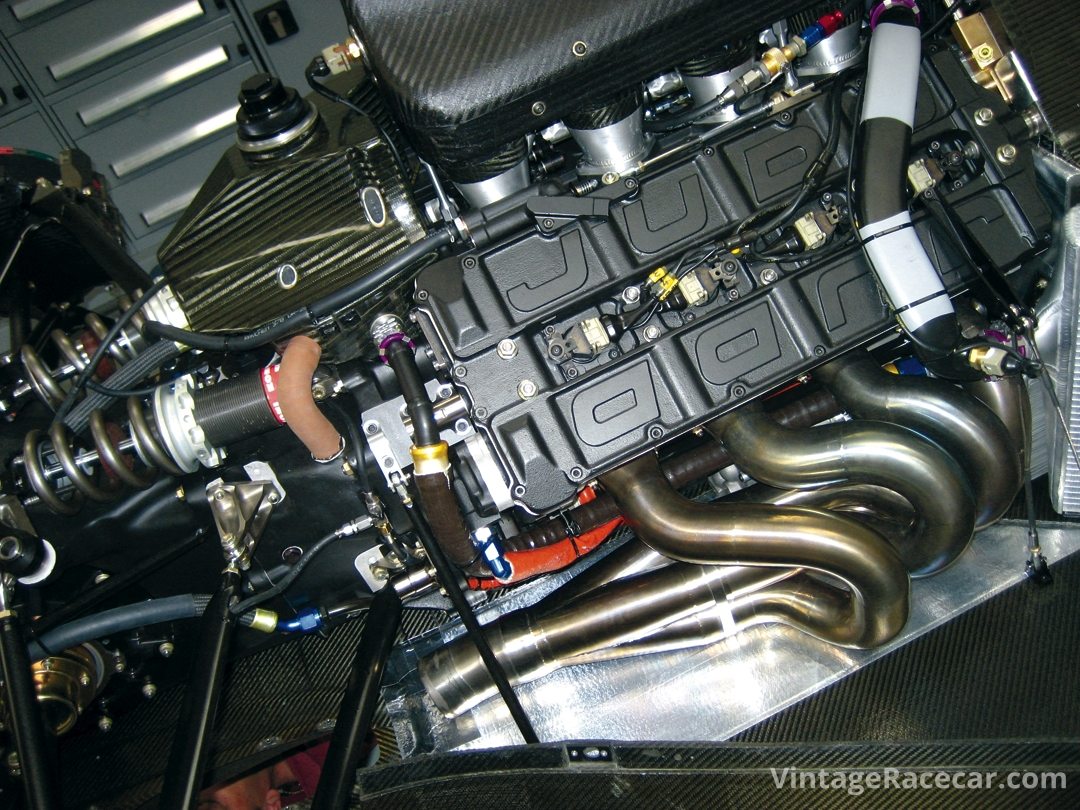

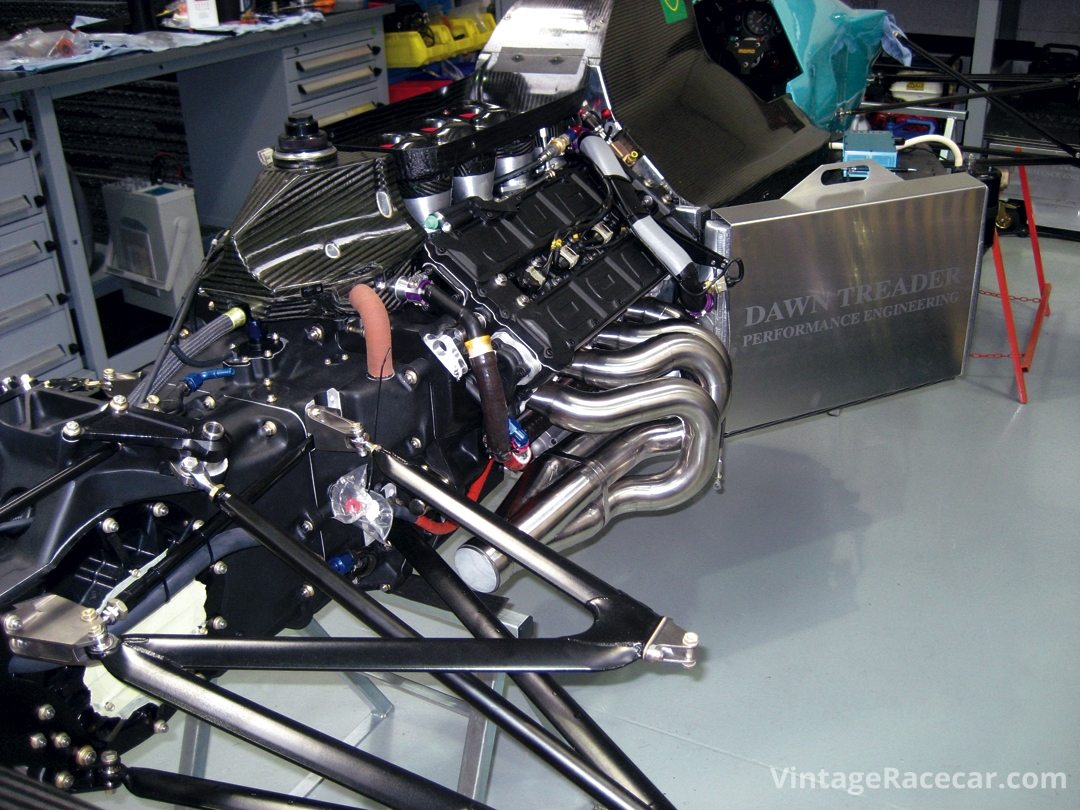

The bespoke, narrow-angled Judd EV V8 was used once again, a very ingeniously engineered power unit given the budget available. This allowed the cam covers to be housed within the same profile as the drivers’ shoulders and was bolted to the tub. The lack of financial input did make for some compromises in the construction of the unit, however. One particular issue is the fuel rail made of some 16 individually welded parts, which can be an Achilles heel if not regularly crack tested. However, by and large this was an astonishing piece of engineering given the finances. Leyton House’s own 6-speed longitudinal gearbox was attached to the engine via a bellhousing. Newey’s experience in Indycar led to his ideal thinking for radiator and cooling layout. A V-shaped keel directed a smooth airflow to the sidepods accommodating the radiators. This V-shaped keel was also used in later Newey cars both at Williams and more recently at Red Bull. At the front, the nose is bolted to the tub. Newey had looked at the nose and the front wing as being a complete aero device, one piece, rather than having a wing section attached to the nose section. This was probably the first time this was seen in F1. It wasn’t just driver needs that were compromised by Neweys’ strict design concept, but mechanics’ too. There was very little or no room to work within the engine bay, everything being a slave to aero demands. For example, the gear linkage runs through the fuel cell via a bonded rubber tube with a carbon insert to encapsulate the horrendously complicated assembly. Despite this, it is possibly one of the better-designed systems of the era with very little articulation through universal joints giving a more positive feel to the gear shift. The car, as a whole, is encased in the very distinctive Leyton House Miami Blue painted skin and is very striking in appearance. However, there was a serious flaw in the aero package. At an early stage of the design, engineers working on 1/3-scale models were unaware of a failing with the wind tunnel. Apparently, the integrity of the tunnel floor was compromised. As the car relied heavily on the aero package, the critical calculations and setup from numbers acquired from wind tunnel data were unreliable. Once the season got under way these flaws became very much apparent at early races.

The first round of the 1990 season was at Phoenix, the Iceberg United States Grand Prix. While both cars made the cut and qualified for the race, embarrassingly Gugelmin and Capelli were on the back row of the grid. In the race, Capelli lasted just 20 laps retiring with electrical issues. Gugelmin fared a little better finishing as the last classified runner in 14th place, completing 66 of the 72 laps. It was off to Interlagos, Brazil, for Round 2 just two weeks later, but the very bumpy circuit caused havoc with the new aero settings and both cars failed to qualify. The car was very tight and stiff with minimal suspension travel, both motion ratios and wheel rate support this. However, rigidity was needed to take full advantage of the aero package, but this meant it was very sensitive to its attitude with the ground in both pitch and roll—the chassis yearned for the ability to allow a more generous setup that would negate, or be less compromised by, uneven track surfaces. The San Marino GP at Imola was a month away, so time to regroup. It is at this time our chassis came into being.

CG901 chassis 3

Interim fixes were urgently required prior to a whole new re-think and a “B” specification of the car being conceived. The Imola car relied upon the basic structure of previous chassis, but there were significant tweaks in several areas, including new sidepods, new suspension geometry, a modified front wing section and rear diffuser. While there were technical issues with the wind tunnel, the finger was firmly pointed at Adrian Newey to deliver a competitive package as soon as possible. At Imola the team progressed, the new modifications obviously making a difference. Gugelmin qualified 12th on the grid (Capelli 18th in the sister car). In the race, however, engine problems led to Gugelmin’s retirement on Lap 24.

With its tight, twisty layout and normal road surface, Monaco was always going to be difficult for a car that wanted to stretch its legs. And so it was—despite a front wing upgrade using a secondary flap—that Chassis 3 failed to qualify. Both Montreal and Mexico, the next races venues, brought more doom and gloom with Chassis 3 failing to qualify. Capelli fared a little better at Montreal, starting 24th and finishing 10th, but then failed to qualify in Mexico. The problem was lack of speed due to setup difficulties. Inevitably, the team as a whole were demoralized by continued poor performances. Adrian Newey was in the firing line just like a manager of a football team suffering a number of defeats. Some records suggest “he was pushed,” others say “he jumped,” whatever, Newey left before he could see the fruit of his labor materialize at Paul Ricard—venue for the French GP and the debut of the new B-specification car.

The new car sported significant aero changes, a complete new underbody, a lower arched diffuser incorporating exhaust exits and redesigned sidepods. The front wing was new too, using a novel T-tray attachment, which is exactly what they were made of—reputedly from McDonalds! The issue was found during a test session when it was deemed necessary to extend the front wing flaps. One of the Leyton House “lads” was tasked with finding suitable, readily available material to construct the extension pieces—hence the “Golden Arches” restaurant inadvertently coming to the rescue.

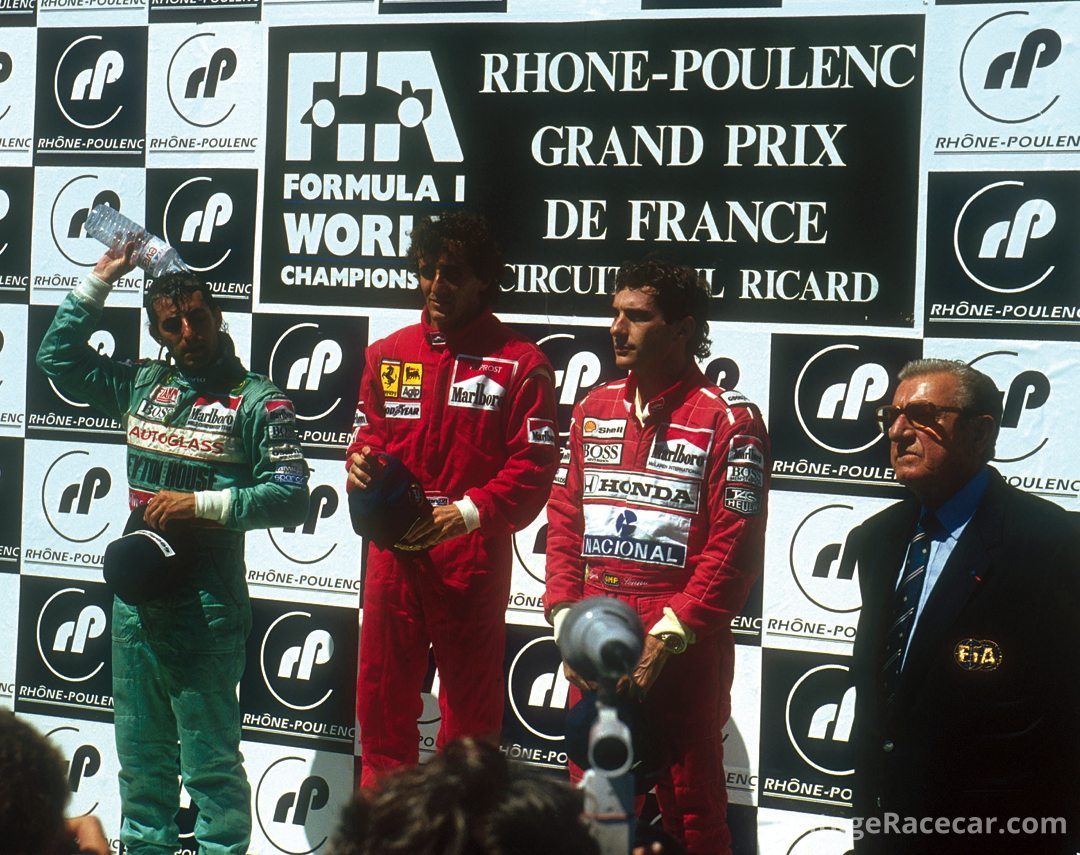

For the first time, the surface of the Ricard circuit was ultra smooth and an ideal testing ground for what could be achieved with this new aero package. The French GP was a huge success, the remedial action taken by the departed Newey had worked. The team were jubilant. Capelli took the driver’s seat in Chassis 3 qualifying in 8th, with Gugelmin now in a sister car starting from 10th on the grid. A major part of the success of the car, at Paul Ricard, was due to excellent tire wear characteristics. It was therefore decided to start both cars on the softer “C” grade Goodyear tires, running the whole race on one set. Capelli’s mechanic, Paul van der Lowen recalls, “Gustav Brunner was very confident. He had told me the night before, leave the car exactly as it is ‘Don’t change a thing, Ivan is very happy.’ He knew we could do the whole race on one set of Goodyears and all other teams would have to stop. That evening, after qualifying, Gustav again said ‘Don’t touch the settings, leave the car as it is, just make sure it will do the race,’ which we (Ian “Sly” Stone and Gary “Gadget” North – sadly no longer with us) did.” This strategy proved very effective, as the cars were 1st and 2nd for 20 of the middle laps, embarrassing the more powerful V10 and V12 cars. Prost’s Ferrari was the first car to challenge, he overtook Gugelmin who unfortunately retired with engine problems. Capelli was next in line for the Prancing Horse, but held out until lap 78 before losing the lead. Although Chassis 3 experienced fuel pressure problems late in the race, Ivan Capelli held on to 2nd place for a truly remarkable podium position, finishing three seconds in front of Senna’s McLaren. Paul van der Lowen recalls the agony and joy shared by the team, “All I remember is a very long hot race, when we started losing fuel pressure, I was praying for the end. It came, the joy was overwhelming for us all. Gustav (Brunner) jumped the wall to wave at Ivan as he crossed the line. The feeling was incredible, fantastic! Ron Dennis sent down champagne for us. Just two weeks earlier, we had two DNQs. I have done a lot of races since, with many teams, won many races, but NONE gave me the same memories as that weekend in the south of France!” Sadly, Adrian Newey, architect of this amazing feat, was absent from the team. Interestingly, no one else looked to steal his credit.

Chassis 3 was used for the next round at Silverstone, but Capelli was sidelined after 48 laps with fuel rail problems. It was the team spare until Monza where, once again, Capelli drove it, but retired on lap 36 with engine issues. The car remained the spare for the rest of the season.

Preparing and driving Chassis 3

Our car is in the guise of how it appeared at Suzuka for the 1990 Japanese GP. This was the overall “B” spec, but with slight modifications from Chris Murphy who’d taken over design responsibility. The car had a new front wing and a longer nose section than previously.

Preparation to drive a car of this era is significant. The main problem being, in period the car was regularly stripped down, now inactive, it remains static for long periods of time. A considerable amount of work is required to put a car of this nature into “hibernation” and much more to bring it back to life again. The first thing to awaken the car is to remove all the anti-corrosion additives to the water system necessary when the car is stored for long periods of time. Bleeding the water system is another chore, but extraordinarily difficult, as the bleeds are located in the most inaccessible points you could imagine. Brake and clutch fluids are changed religiously, they need replacing as they are hygroscopic and have a tendency to take water in. Engine oil is the next on the list for replacement as it is removed for storage purposes for many reasons. First, crank seals will deteriorate if left immersed in oil. Also, engine oil will obviously make its way from the tank to the sump with long periods of standing. It could also permeate into the clutch housing, causing problems. The drives to the scavenge pumps can break when the engine is first “spun over” unless great care is taken. Fuelling for the first time after storage is problematic too, due to the brass housing of the fuel pump (much like the Cosworth-Lucas pumps) bolted to the carbon body of the car up by the top right-hand side of the engine. Sometimes the housing bends, causing the pump to fail. To alleviate this problem a cap full of two-stroke oil is thrown in to lubricate the pump—something learned from period mechanics, but much to the disapproval of BP—fuel sponsor for the car. Once fully prepared, the next operation is to pre-heat the liquids to about 60-degrees Celsius, via a bespoke external heat exchanging unit. The engine is then spun over to ensure the sump has been evacuated and the heaters removed. For safety reasons, a minor modification from period to our car is a high-pressure fuel pump positioned directly inside the fuel cell. This is used to prime the system and is operated by a simple toggle switch subtly located on the dash—an untrained eye would probably not even notice it. This whole preparation procedure takes around a day to complete due to the cramped layout of the car.

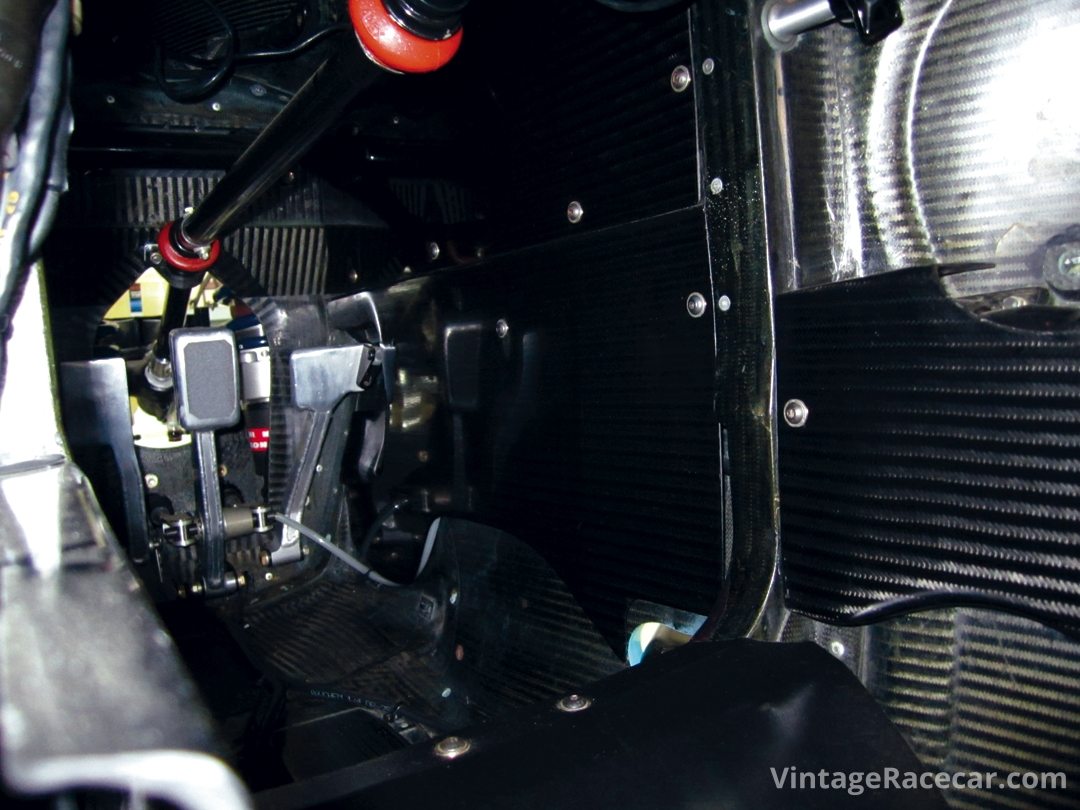

With the car readied for action the first task is getting into the compact cockpit. Of course, the detachable steering wheel is removed for driver entry. Standing on the bottom of the chassis – there is no seat….. is the first step, then carefully holding onto the sides of the cockpit and using your body weight and arm strength to lower yourself carefully down, while “worming” your way into the car. Once in position, with belts tightened, steering attached and visor down you can experience some claustrophobia. There is definitely a feeling of becoming part of and “at one” with the car. With the bodywork covering the steering wheel position there is absolutely no indication of where your hands are positioned—it’s all blind and done by feel, you can easily catch your knuckles on the side of the bodywork. The gearshift is on the right and again very tightly packaged and operated in an H-gate fashion. First gear is forward, then back down to second, up to third until in top which is sixth—the shift is both smooth and precise. However, due to the lack of space, concentration is paramount when changing from one gear to another. The small period screen has been removed to aid vision; the screen was all part of the aero package, but for this run is not required. Despite its complications the car is easily operated trackside by just two people, rather than the infantry required for a modern racer.

With all systems up to temperature the signal to start is given and the Judd engine blasts into life with a solid roar. As all temperatures and pressures are correct and rpm at 5,000, the car pulls away purposefully. However, a racing or competition start would demand 10,000 rpm (it is capable of 12,000 rpm, but there’s no point in breaking the car). Indeed, changing up and through the gears for the purpose of this test 10,000 rpm is the signal to move up through the gear range. In first gear, 10,000 rpm gives around 60 mph progressing to 176 mph for the current gearing at 10,000 in sixth gear. If the revs are not kept up in the higher gears there is a tendency for the engine to give the impression of stalling, immediately dropping to a lower gear if necessary. Traction is great, given that we’re on wet tires, but second is selected almost straight away to lose any wheelspin. The car is set up and perfectly balanced, not pulling one way or the other. It’s very nimble, and turns in and out very well. At every increase in speed you can feel the aero package working, pushing the car into the road surface and gripping intensely. It’s hard to imagine the initial problems the car endured when first put to track. At this moment, you feel at one with the car, the engine full of life and power, a gearbox so smooth, a chassis so nimble and precise, and the car as a whole sticking to the road eager to go faster—we are aboard a proper racing car. Don’t get me wrong it’s easy to make a mistake, but if the car begins to slide one way or another a quick blast on the accelerator regains control. Conversely, backing off, you can feel the car loose power and grip quite quickly. The stiffness of the suspension is apparent, feeling every bump in the road surface truly from the seat of your pants!

Andy Wallace, who test drove the car in period, had the following comments, “The first thing that I remember was the huge amount of aero drag the car had. Probably less than today’s F1 cars, but so much more than the Group C and LMP cars I am more familiar with. It also still had a six-speed H-pattern gearbox, with the three gates all very close together. If you missed the fifth to sixth shift for any reason, the high drag slowed the car so quickly that you had to re-select fifth again, rather than sixth. Secondly, the exhausts exited directly into the rear diffuser. To get the best from the car in the quicker corners you had to perfect the art of going back to full throttle just after turning-in, to make use of the extra downforce created by the exhaust gasses. This was more difficult than it sounds…. When you entered the corner at, or slightly over, the limit it was difficult to make yourself push the throttle fully down. Of course, that was exactly what you needed to do to stay on the road!”

Conclusion

The car as a whole can be described as a work in progress, which due to circumstances was never finished, or reached full potential. Or did it? In a recent interview, Newey still holds the belief that Leyton House could have been the Red Bull of the 1990s had he stayed and worked further. After leaving, Williams Grand Prix signed him, recognizing his ability and nurturing his understanding of aerodynamics. Significantly, if the CG901 and the Williams FW14 were placed side by side the similarities would become very apparent. So, with initial reliability issues sorted, the Williams FW14 went on to win a significant number of races in 1991. Of course, in 1992 Williams adopted active suspension with the AP tripod active suspension system on the FW14B, winning the World Championship in 1992.

In every era of motor racing there is always someone who dares to be different, over the past 25 years it is clear that Newey was not only responsible for great success at Williams, but McLaren and Red Bull too. He has become extremely well respected in Grand Prix racing today. As he prepares to take a “back seat” in 2015, moving to pastures new, it will be interesting to find a newcomer to fill his shoes. At a recent test day at Silverstone, Adrian was reunited with CG901/3, which he described as, “Fitting like an old glove.” He remains extremely fit these days and easily slid into the cramped cockpit. He thoroughly enjoyed the laps in the car that heralded his arrival as a legendary designer.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine Judd EV V8, 3500-cc 640bhp@11,750 rpm

Gearbox Leyton House

Driveshaft Leyton House

Clutch AP

Suspension Double wishbone pushrod front and rear

Dampers Koni

Wheels 13-inch Front and rear, 11.75-inch wide front 16.30-inch wide rear

Tires Goodyear in period; now Avon

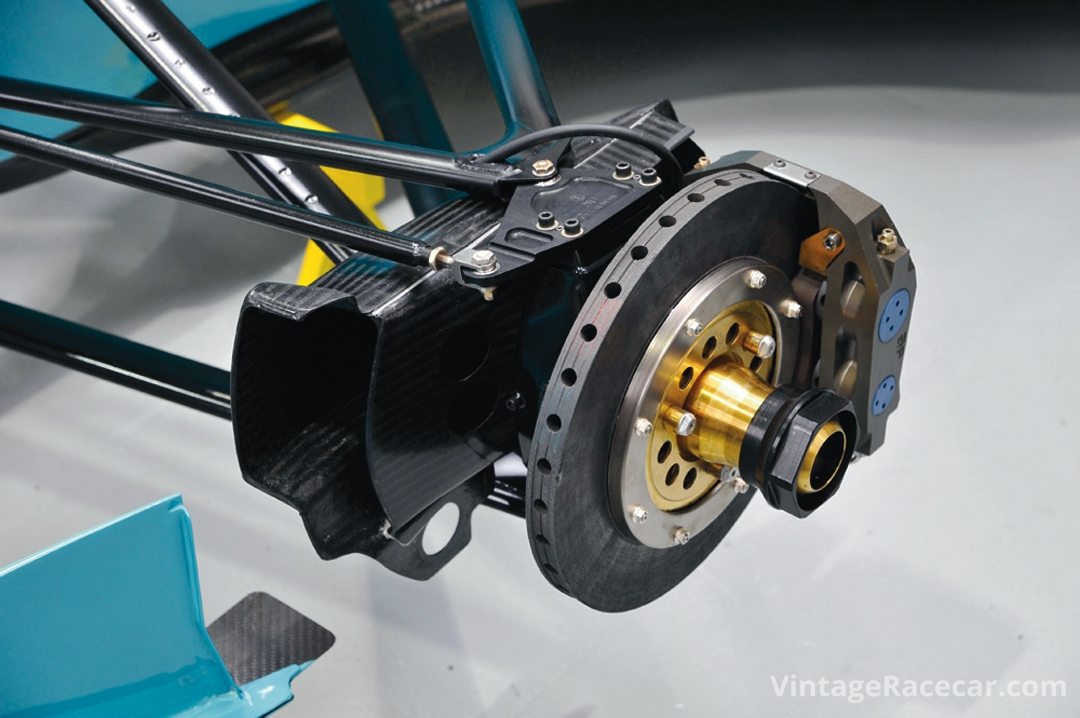

Brakes (period) SEP/Carbone Industrie discs/pads; Brembo calipers Brakes (now) Hitco with AP calipers

Steering Leyton House

Fuel tank ATL

Wheelbase 113.70 inches

Front track 71.30 inches

Rear track 68 inches

Weight 113.30 pounds

Resources

Very grateful thanks go to a number of people; first and foremost, to Patrick Morgan of Dawn Treader Performance. Gary Ward of GW Motorsport. Former Leyton House Mechanic, Paul van der Lowen. Former Leyton House test drivers, Bruno Giacomelli and Andy Wallace.

Bibliography

Autocourse 1989 – 1990,

Hazelton Publishing.

Autocourse 1990 – 1991,

Hazelton Publishing.

Murray Walker’s 1990,

Grand Prix Year,

Hazelton Publishing.

March, The Grand Prix

and Indycars by Alan Henry

A-Z of Formula Racing Cars,

David Hodges

Grand Prix Who’s Who

by Steve Small

Periodical Publications

Motor Sport

Autosport

F1 News

Other Sources

Video – BBC Grand Prix & Eurosport – Grand Prix programs of 1990 season

Internet – www.racingsportscars.com / www.f1-grandprix.com