Lola Cars

Research, History, Reviews, Media & More

Introduction / Featured Stories / Model Guides / News & Updates / The Birth of Lola

Lola Cars: British Racing Innovation

Lola Cars is a name that holds a special place in the history of motorsport, known for its innovative designs, engineering excellence, and success across a wide range of racing disciplines. From humble beginnings in a small garage to becoming the largest independent racing car manufacturer in the world, Lola's journey is a testament to the vision and ingenuity of its founder, Eric Broadley. This post explores the founding of Lola, its rich history, the iconic car models it produced, and the milestones that have defined its legacy.

The Founding Vision: Eric Broadley and the Birth of Lola Cars

Lola Cars was founded in 1958 by Eric Broadley, an engineer and racing enthusiast from Bromley, England. Broadley’s passion for racing and his engineering talent led him to build his first car, the Lola Mk1, in a small garage. The Mk1 was a lightweight sports car designed for club racing, and it quickly proved successful on the track. The car's performance caught the attention of the racing community and established Lola as a brand to watch.

Broadley’s vision for Lola was to create high-performance racing cars that could compete at the highest levels of motorsport. His approach to car design was characterized by innovation, attention to detail, and a relentless pursuit of performance. These qualities would define Lola’s success in the years to come.

The Evolution of Lola: From Club Racing to Global Success

Lola’s rise to prominence in the racing world is marked by a series of groundbreaking car models and achievements across various racing disciplines:

Lola Mk1: The Beginning of a Legacy (1958):

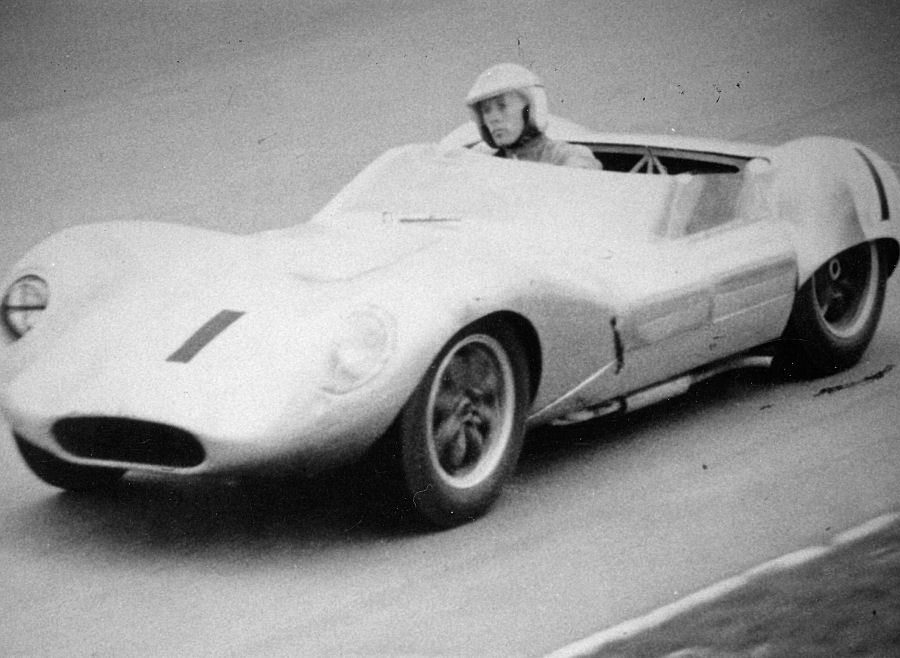

The Lola Mk1 was the first car produced by Eric Broadley, and it laid the foundation for the company’s future success. The Mk1’s lightweight design and excellent handling made it a formidable competitor in club racing, and it quickly gained a reputation for performance. The success of the Mk1 established Lola as a brand capable of producing race-winning cars.

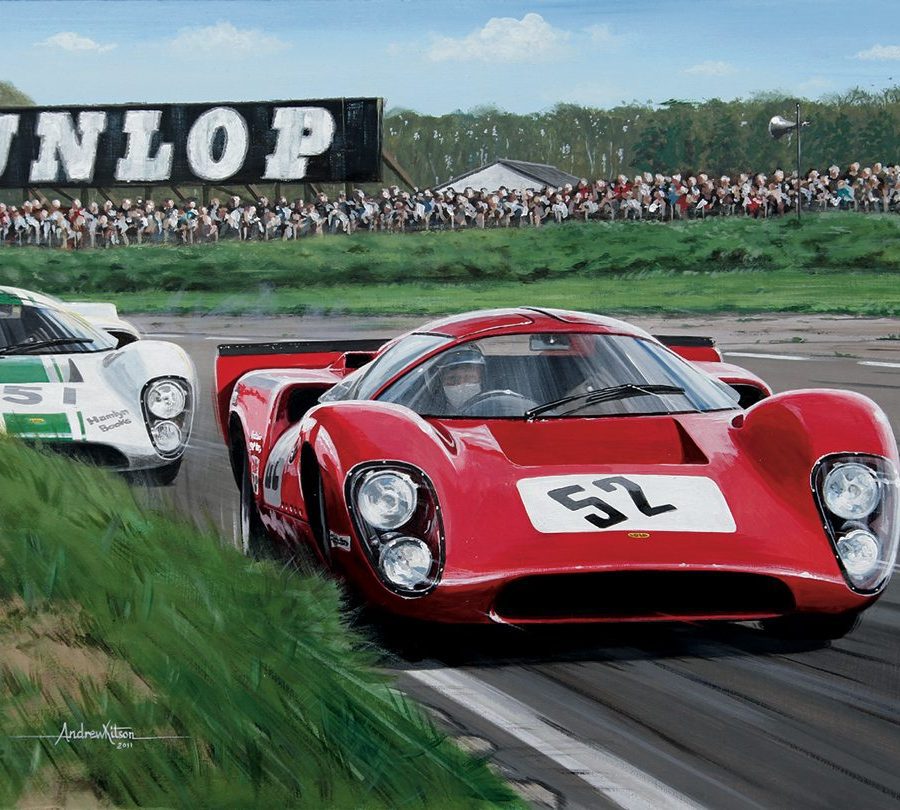

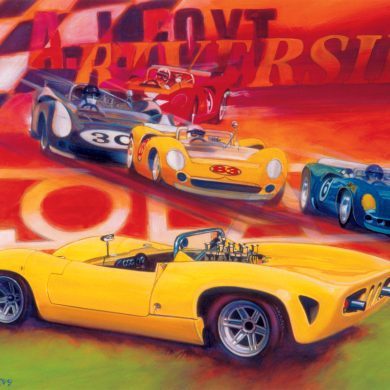

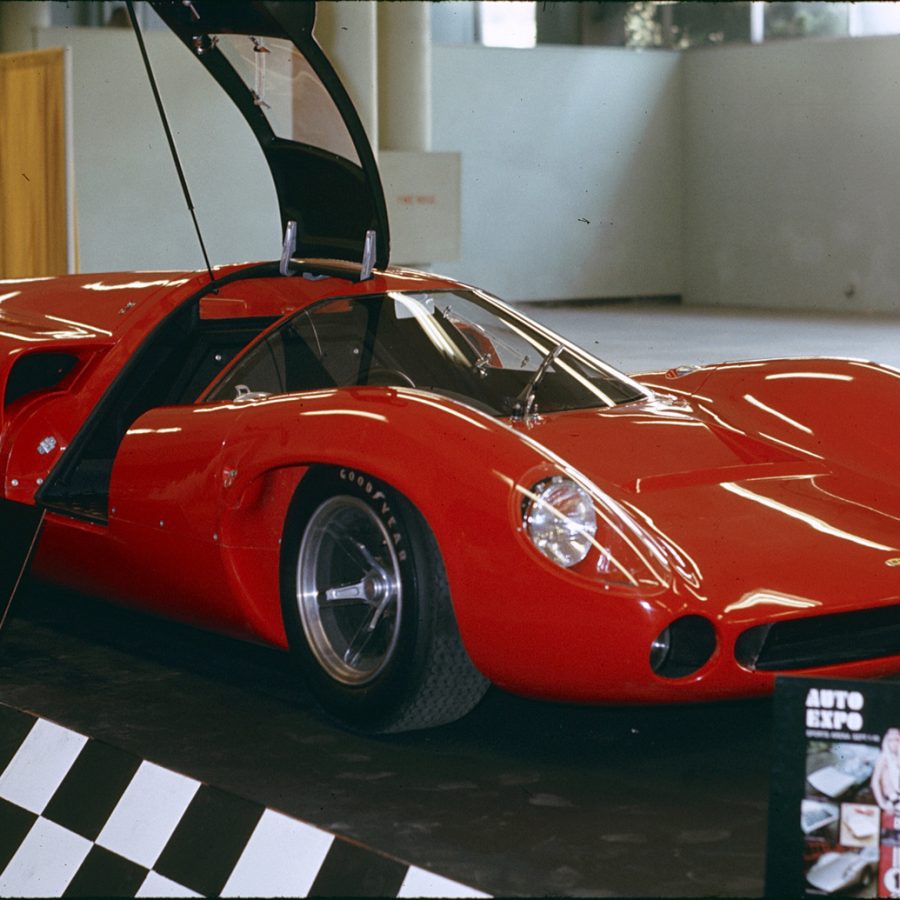

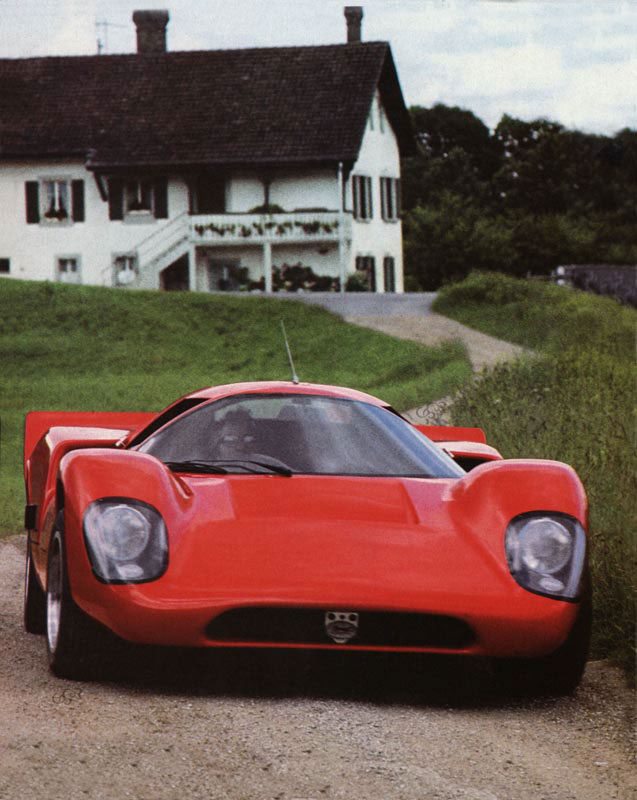

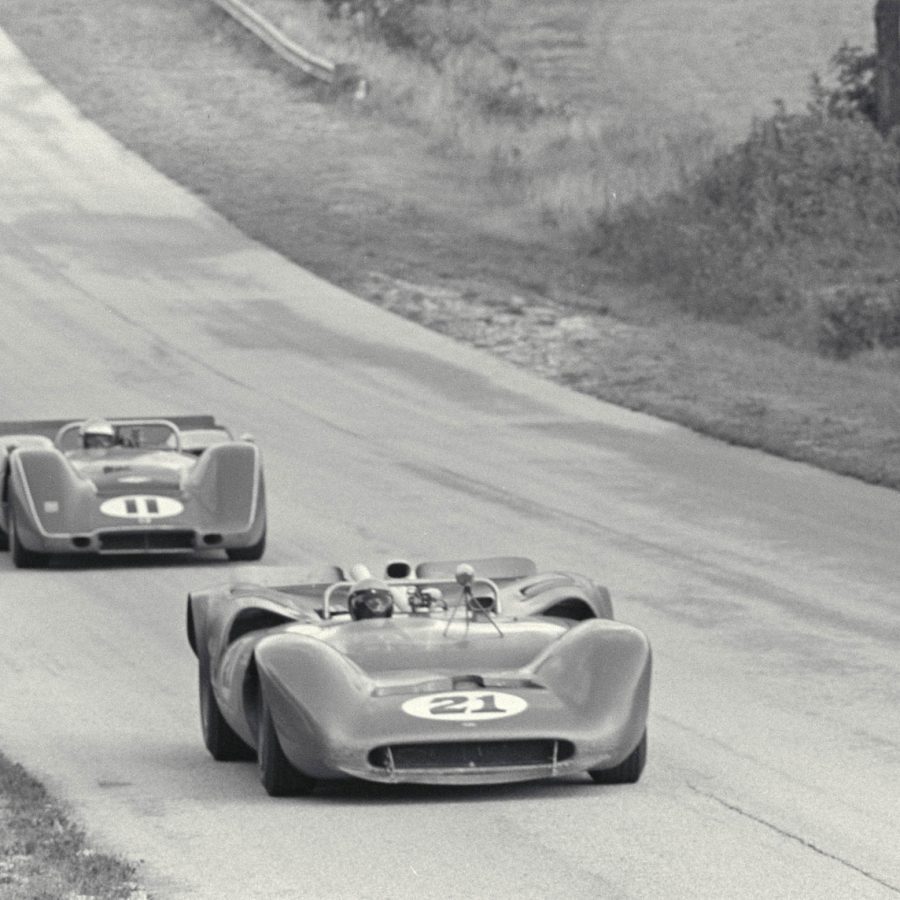

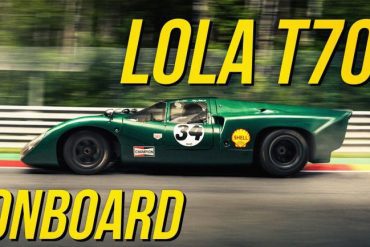

Lola T70: An Endurance Racing Icon (1965):

The Lola T70, introduced in 1965, is perhaps the most iconic car ever produced by Lola. Designed for endurance racing, the T70 featured a powerful V8 engine and an aerodynamic body, making it highly competitive in races like the 24 Hours of Daytona and the 12 Hours of Sebring. The T70’s success on the track and its stunning design made it a favorite among drivers and fans alike. The T70 remains a symbol of Lola’s engineering prowess and is still celebrated in historic racing events today.

Formula 1 and IndyCar Involvement:

Lola Cars made several forays into Formula 1, supplying chassis to various teams over the years. The most notable of these was the partnership with Honda in the 1960s, where the combination of Lola chassis and Honda engines showed great promise. Although Lola never achieved sustained success in Formula 1, its involvement in the sport demonstrated the company’s ability to compete at the highest levels.

Lola’s impact on IndyCar racing, however, was much more significant. Lola chassis were used by several winning teams at the Indianapolis 500, one of the most prestigious races in the world. Lola cars secured victories at the Indy 500 in 1966, 1978, and throughout the 1980s, solidifying Lola’s reputation as a premier manufacturer of racing cars.

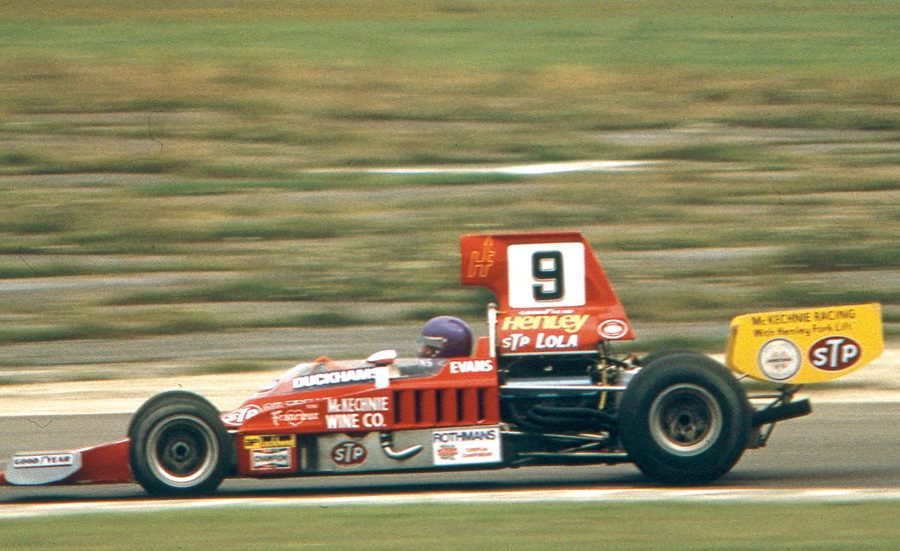

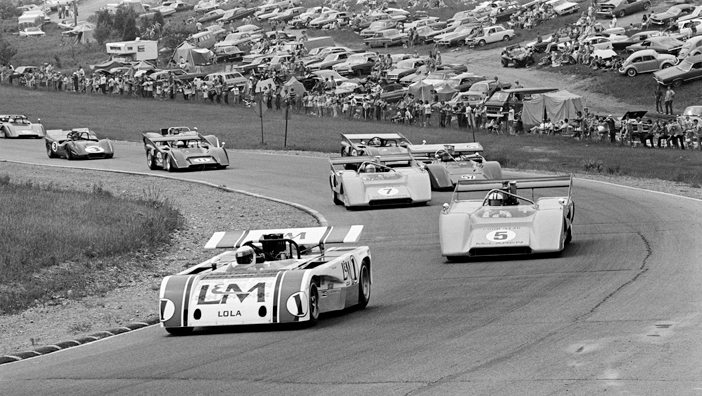

Dominance in Formula 5000 (1970s):

During the 1970s, Lola cars were dominant in Formula 5000 racing, a category that featured large, powerful engines. The Lola T332, in particular, became one of the most successful Formula 5000 cars ever, with numerous race wins and championships to its name. The T332’s success highlighted Lola’s ability to design cars that were not only fast but also reliable and easy to drive.

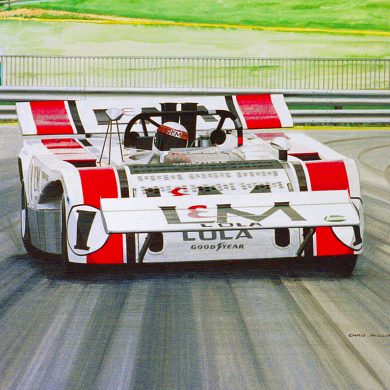

Versatility Across Disciplines:

One of the hallmarks of Lola Cars was its versatility. The company produced cars for a wide range of racing disciplines, including sports cars, Formula 1, IndyCar, and even hill climbs. This versatility made Lola a go-to manufacturer for many racing teams around the world, and it cemented Lola’s status as a leader in motorsport.

Special Milestones and Achievements

Throughout its history, Lola Cars achieved several significant milestones and made lasting contributions to the world of motorsport:

Pioneering Monocoque Chassis Design: Lola was one of the early adopters of the monocoque chassis design, which replaced the traditional spaceframe chassis in race cars. This innovation significantly improved the safety and rigidity of racing cars and became the standard in motorsport.

Endurance Racing Success: The success of the Lola T70 in endurance racing, particularly at events like Daytona and Sebring, showcased the brand’s engineering excellence and ability to build cars that could compete against the best in the world.

Impact on IndyCar Racing: Lola’s dominance in IndyCar racing, including multiple victories at the Indianapolis 500, solidified its reputation as a premier manufacturer of open-wheel racing cars. Lola’s chassis became the benchmark in the series for many years.

Eric Broadley’s Legacy: Eric Broadley’s vision and engineering talent were the driving forces behind Lola’s success. His contributions to motorsport, particularly in the areas of lightweight construction and aerodynamics, continue to influence car design today.

The Enduring Legacy of Lola Cars

Lola Cars’ legacy is one of innovation, engineering excellence, and success across a wide range of racing disciplines. The cars produced by Lola during its peak years remain highly sought after by collectors and racing enthusiasts, and they continue to compete in historic racing events around the world. Although Lola Cars went into administration in 2012, the brand’s intellectual property and legacy are still preserved, with ongoing support for historic racing and engineering projects.

Eric Broadley’s impact on the world of motorsport cannot be overstated. Lola’s focus on lightweight design, aerodynamics, and engineering excellence has influenced a generation of race car designers and continues to be felt in the racing world today.

Lola Cars

Founded: 1958 (original), 2024 (revival)

Founder: Eric Broadley

Defunct: 2012 (original)

Headquarters: England, UK

Key people: Till Bechtolsheimer (Chairman)

Owner: Till Bechtolsheimer

Did You Know

Lola Cars was founded in 1958 by Eric Broadley in a small garage in Bromley, England. What started as a modest operation quickly grew into one of the most successful racing car manufacturers in the world.

Lola was one of the early adopters of the monocoque chassis design, which replaced the traditional spaceframe chassis in race cars. This innovation significantly improved the safety and rigidity of racing cars and became the standard in motorsport.

The first car produced by Lola, the Lola Mk1, was an immediate success in club racing. It was a lightweight sports car that caught the attention of racers and set the stage for Lola’s future success in international motorsport.

Lola cars were dominant in Formula 5000 racing during the 1970s, winning multiple championships. The Lola T332, in particular, became one of the most successful Formula 5000 cars ever, with numerous race wins and championships to its name.

The Lola T70, introduced in the 1960s, became one of the most iconic endurance racing cars of its time. With its powerful V8 engine and aerodynamic design, the T70 was successful in races such as the 24 Hours of Daytona and the 12 Hours of Sebring.

More Lola Cars

John Hurabiell, 1956 Lotus 11, Turn 5

John Hurabiell, 1956 Lotus 11, Turn 5The Birth of Lola

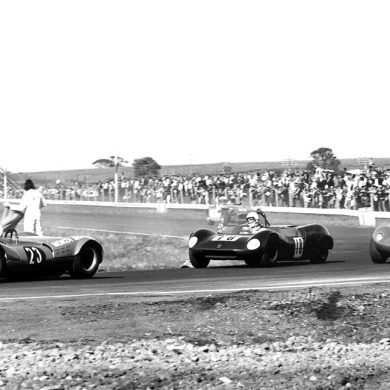

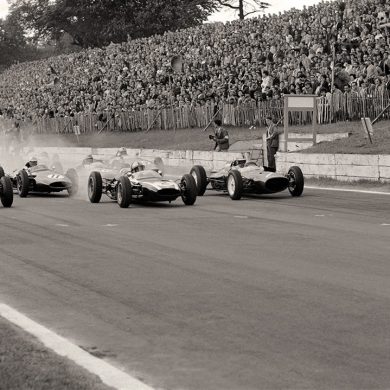

One of the most memorable motor races I have ever seen was broadcast from the 1959 Easter Monday Goodwood Meeting and it was for 1100-cc sports cars. For three years, the class had been dominated by the Lotus Eleven, but the top three spots on the grid were filled by Lola, a new marque, with an Elva Mk IV in fourth.

Thanks to the Coventry Climax FWA engine, the 1100-cc sports racing class had become the category for the ambitious young driver with his eye set on higher things. The Lotus Eleven had seen off competition from at home, mainly Cooper, and overseas, mainly the Etceterini. It reigned supreme in SCCA events and they were important to all small constructors because America was where the money was. And not only had it won classes at Le Mans, it had broken the French grip on the Index of Performance. The Eleven dominated its class like no other car of its time.

The three Lolas ran away and hid from the opposition and all three drivers, Peter Ashdown, Peter Gammon and Michael Taylor had all previously raced Lotus. Indeed, in 1954, Peter Gammon had been, with Colin Chapman and Mike Anthony, a member of the very first Team Lotus. The race caused a sensation and Lola was established. For this teenaged fan of motor racing, it was a seminal moment: in motor racing, nothing was writ in stone; you are only as good as your last race.

Eric Broadley had ambitions as a race driver and he and his cousin, Graham, had built a Ford-engined special, named Lola, for the 750 MC’s 1172 championship. Eric won the 1957 series, beating several Lotus drivers, and with it, the Colin Chapman Trophy. The first Lola was sold on to a guy who re-named it “Lolita” and who also won the 1172 championship and the Colin Chapman Trophy.

To achieve the next step up, Eric wanted a Lotus Eleven, but that was beyond his earnings as a quantity surveyor. It was reported at the time, and often repeated, that he was an architect. He had studied architecture, but was working as a quantity surveyor. Eric had an eye for a structure and an understanding, then rare, of suspension geometry.

Eric designed a car smaller and lighter than a Lotus and the spaceframe was bronze-welded rather than using fusion-welding which was normal at the time. Eric went to ace body maker, Mo Nunn, and in Nunn’s workshop was a shell intended for a Tojeiro-Climax, but never claimed. Mo Nunn cut and shut the shell to suit the Lola, production cars had a slimmer body with a smoother front treatment.

Frank Costin had designed all of Lotus’s aerodynamic bodies, but Chapman never paid him so he left. The body of the Lotus 17 was run up by Charlie Williams and Len Pritchard and it was based on the Eleven, but it had no science behind it. Come to that, neither had the Tojeiro/Lola body. Tojeiro bodies were imagined by an artist, Cavendish Morton, who sent a three-quarters front painting to Mo Nunn.

“Cavvy” died in 2015 a few weeks shy of his 104th birthday. Celebrated for his use of color and light, and his seascapes, his work is in some important collections. He is why Tojeiro cars were often very pretty.

Eric debuted his second special in late August, 1958, at Brands Hatch, where he came the first driver to lap the circuit in under a minute. Information was then hard to come by for the average fan. We knew that Eric and his car was quick, at the couple of meetings where he had raced at the tail end of 1958. What we did not know was the backstory.

Colin Chapman assessed the new design and knew that the Lotus Eleven had been upstaged. When he thought that he had been bested, Chapman could adopt a narrow focus. The result was the Lotus 17, his first setback, because his only criterion was that it had to be smaller than the Lola. His assistant designer, Len Terry, pointed out that Chapman’s proposed suspension would not work because it did not have sufficient room inside the body to operate.

Len was shown to be right. Chapman had taken the suspension unit, the MacPherson strut, made minor modifications and launched it as the Chapman Strut and the automotive media of the time was so entranced by Colin’s charisma that it did not question his chutzpah. The Lotus 17 was launched with “Chapman strut” front suspension and when the car was cornered hard, the front suspension bent and locked up causing extreme oversteer, then the suspension was released, giving understeer.

Late in the day, the Lotus 17 was equipped with double wishbone front suspension, which Len Terry had advocated all along. Lotus even gave the update free to customers—something which must have hurt. It then performed quite well, but by then Lola was king of the 1100-cc class. Len Terry was credited/blamed for the Lotus 17, but Chapman was responsible for the flaws in the design.

After his sensational debut at Brands Hatch, in 1958, Eric Broadley’s story followed an established pattern: man builds special to go racing; another man wants to buy said special; the special builder becomes a constructor. That was how it was for Chevron, Cooper, Crossle, HWM, Mallock, Lotus and Tojeiro. The last man to fit the mold was Adrian Reynard in 1974; the rise of the one-make formula now makes it virtually impossible, which is motor racing’s loss.

Eric had orders, but no premises and then a local motor dealer, Rob Rushbrook, offered him space in his premises in Bromley, south London. Rob remained in charge of Lola production until he retired in the late 1980s, the ethos of Lola was loyalty and Graham Broadley was also a director. It was Graham who suggested the name, Lola. A popular song of the time was “Whatever Lola wants, Lola gets” and the name had echoes of Lotus. Eric told me that he simply went along with Graham’s suggestion.

Eric still had ambitions as a driver and during the winter of 1958/’59, took his car to a circuit to test it. Also there was Peter Ashdown, who had been a member of Team Lotus in the past and Peter was testing the new Elva Mk IV, which he liked. Eric suggested that Peter try his car and the lap times Ashdown set told Eric that he was not going to be a World Champion and Peter no longer wanted to drive an Elva. For three years from the beginning of 1959, Peter Ashdown was Lola’s works driver and occasionally Eric was co-driver in endurance races.

A note about Elva, the Mk IV was the marque’s first design by Keith Marsden. Colin Chapman was known to refer to Cooper as “those (adjective deleted) blacksmiths” but at his agricultural college, Keith had won the prize for top farrier. In later years, he worked on prototypes for Ford (GB).

Elva had a higher profile in the States than back home but then Frank Nichols, the founder, resented expenses such as a works driver. Moreover, the U.S. importer was Carl Haas who knew a thing or two about shifting cars. SCCA racing was then strictly amateur and drivers preferred cars to oversteer, while optimum performance came with cars, like the Lola Mk 1, which understeered on the limit. Keith Marsden designed his cars for SCCA racing because that is where the money was and if you are not making money pretty soon you are not making cars.

The Lola Mk1, as the second Lola became, was the last successful front-engined sports racer and it dominated the 1100-cc class in 1959. During that year Brits looked at the growth of Formula Junior in foreign parts and decided to join in. The first important FJ race in Britain was at the 1959 Boxing Day Brands Hatch meeting. It was won by an Elva-DKW driven by Peter Ardundell with Peter Ashdown in the first Lola Mk 2 in second place. Both were front-engined and the Lola won praise in the press for its handling.

Lotus was entered with the prototype 18, which was unsorted and had engine problems. Autosport dismissed the Lotus as looking like “a shoe box with dustbin lids for wheels.” Within weeks the 18 was winning in F1, F2 and Formula Junior.

The meeting also saw Jim Clark make his single-seater debut, in a Gemini, a Len Terry design. It was the last time he raced other than in a Lotus.

Eric had no choice but to design a front-engined car, which most Formula Junior cars were. It was during 1960 that he met Mike Hewland who agreed to make a suitable transmission for a mid-engined car, the Lola Mk 3. Apart from there being no available gearbox for a mid-engined car, the case for the engine behind the driver had not been made despite the success of Cooper.

Coopers were light and had a small frontal area and those were the qualities people noticed, it was generally agreed that Cooper design was crude. Lightness and a small frontal area guided Chapman on the Lotus 12 and 16 single-seaters, as they did other makers, particularly of FJ cars. Coopers were rather more than that and they were developed by Jack Brabham who has had no peer as a development driver at any time.

That 1100-cc race at Goodwood saw the start of Lola as a constructor and in the future lay many ups and downs. Peter Gammon retired from racing soon afterwards on the prediction of a medium or some such woo-woo merchant. Peter Ashdown was Lola’s works driver until early 1962. Perhaps his greatest drive was in the 1960 Nürburgring 1000-Kms. Peter had to make up time after his co-driver, Broadley, E, had decided to explore the countryside. In playing catch-up, to win the class, Peter sliced more than a minute from the class lap record.

Michael Taylor bought a Formula One Lotus 18 and during practice for the 1960 Belgian GP he crashed heavily due to a weld in his steering column breaking. Michael was paralyzed for a time and later participated in long distance rallies. He sued Lotus and won an undisclosed sum. That race saw Stirling Moss survive a near-fatal crash when the rear suspension of his Lotus 18 collapsed during practice. It also saw the deaths of Chris Bristow and Alan Stacey.

Eric took no chances with customer safety and his first assistant designer, Tony Southgate, recalled that he and Eric spent half the year with a pencil in their hands, the other half with a welding torch. Eric undertook all the delicate work and it was a landmark when Tony was permitted to make suspension units.

Eric made his name with an exquisite small sports racer, but he seemed at his best when painting on a large canvas, notably Indycar, Can-Am and F5000/A. His contribution to motor racing history was not only the cars he made, but the engineers he nurtured, and the solid values he represented.

Thor Johnson's 1959 Lotus 17 at turn 11.

Thor Johnson's 1959 Lotus 17 at turn 11.

15 September, 2007: Bob Woodward, 1960 Lola MKII Formula Junior, at the entry to the Carousel during practice for the VSCDA Elkhart Lake Vintage Festival in Elkhart Lake, WI.

Mandatory Credit: Vintage Velocity

15 September, 2007: Bob Woodward, 1960 Lola MKII Formula Junior, at the entry to the Carousel during practice for the VSCDA Elkhart Lake Vintage Festival in Elkhart Lake, WI.

Mandatory Credit: Vintage Velocity