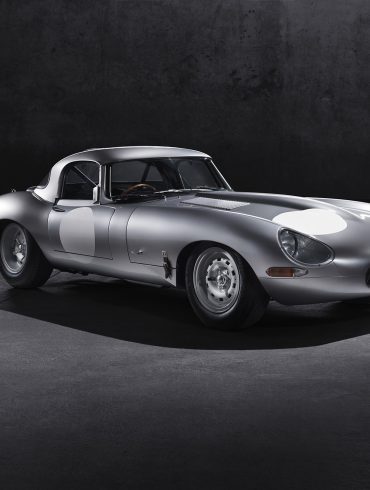

Jaguar D-Type

1954 - 1958

The Jaguar D-Type was a purebred racing machine, a direct evolution of the successful C-Type. With its slippery, wind-cheating body shaped by advanced aviation-inspired aerodynamics, it was built for one thing: outright victory at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The D-Type lived up to its purpose, clinching three consecutive Le Mans wins from 1955 to 1957. Its powerful XK engine, monocoque construction, and superior disc brakes created a potent package that dominated the competition and established Jaguar as a force to be reckoned with in endurance racing.

Overview / The Legend / Model Guides / The Racing / Image Gallery / More Updates

Overview

Designed specifically to win the Le Mans 24-hour race, the D-Type was produced by Jaguar Cars Ltd. between 1954 and 1957. Sharing the straight-6 XK engine and many mechanical components with its C-Type predecessor its structure however was radically different, using innovative monocoque construction and aerodynamic efficiency integrated aviation technology in a sports racing car. Engine displacement began at 3.4 litres, and was enlarged to 3.8 L in 1957, and reduced to 3.0 L in 1958 when Le Mans rules limited engines for sports racing cars to that maximum.

D-Types won Le Mans in 1955, 1956 and 1957. After Jaguar temporarily retired from racing as a factory team, the company offered the remaining unfinished D-Types as XKSS versions whose extra road-going equipment made them eligible for production sports car races in America. Total production is thought to have included 18 Factory Team D-Types, 53 Customer Cars and 16 XKSS versions.

The Details

Continuing their successful motor sports program, Jaguar created the D-Type as a logical progression of the XK120C, or C-Type. After an eighteen month development period, the D-Type was launched and intended to assault the 1954 Le Mans. It won the event three years in a row and became Jaguar’s most successful race car.

After three privately entered XK120s proved competitive at LeMans, Jaguar was motivated to move forward with their own purpose built race car. The result was the XK120C, a car which would win at its very first event, the 1951 24 Hour of Le Mans. This result was achieved again in 1953, with the final version of the XK120-C which featured disc brakes – an automotive first in GT racing.

Even before 1953 victory at Le Mans, it became clear to Jaguar that a new car would be necessary to stay ahead of Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Aston Martin and Maserati. Sir Williams Lyons, the founder of Jaguar, assembled a team of Engineers including Malcom Sayer, an aviation aero dynamist, to create the all-new D-Type.

Winning

Despite being created even before the 1953 Le Mans, the D-Type made it first appearance the following year. Three chassis, #402, #403 and #404 were created after the prototype to specifically race in the 1954 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Unfortunately, two cars dropped out early with brake and transmission problems. The final car, driven by Hamilton and Rolt showed promising resilience, but ended up finishing two minutes behind a 4.9-liter Ferrari. It was one of the closest finishes ever and a bitter disappointment for Jaguar who made Le Mans the point of their competition effort.

Jaguar made up for their losses in 1955, but it was completely overshadowed by the Le Mans tragedy and was only possible with the the withdrawal of Daimler-Benz A.G. and their Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR.

In 1956, Jaguar officially supported teams such as Ecurie Ecosse while they converted the racing department into developing the E-Type. During this time several updates were carried out on the D-Type to keep it competitive. With private entrant E-Types won Le Mans outright with Ecurie Ecosse in 1956 and 1957. During the later, they swept the podium at the 1956 24 Hours of Le Mans with Ron Flockhart and Ivor Bueb of Ecurie Ecosse winning outright. Late in 1957 Jaguar was even considering making a fiberglass body for the 1958 car.

Jaguar D-Type Basics

Manufacturer: Jaguar Cars

Production: 1954–1957

Class: Sports racing car

Body style: Roadster

Layout: Front-engine, rear-wheel-drive

Engine (1954): 3,442 cm3 XK6 Inline 6

Engine (1957): 3,781 cm3 XK6 Inline 6

Engine (1958): 2,997 cm3 XK6 Inline 6

Predecessor: Jaguar C-Type

Successor: Jaguar E-Type

Did You Know?

The iconic tail fin was a key aerodynamic feature that helped improve stability at high speeds. It was so effective that some D-Types raced with a smaller fin for shorter circuits.

The D-Type was one of the first race cars to use a monocoque chassis, where the body forms a key part of the car's structure. This provided greater rigidity and reduced weight.

Some versions of the D-Type had fuel tanks integrated into the tail fin and even the doors, maximizing capacity within the sleek body.

Some D-Types were built with a 'long nose' front section for high-speed tracks like Le Mans, further enhancing their aerodynamic efficiency.

A small number of D-Types, designated the XKSS, were converted from racing spec for road use, making them incredibly desirable and valuable today.

"The D-Type is, I’m certain, the finest sports car yet made in England. One drives it almost by thought alone..."

Mike Hawthorn (Jaguar driver, 1955 Le Mans winner)

The Jaguar D-Type Engineering

Design requirements for the D-Type said it should be lower and shorter that its predecessor. This would help the car achieve a higher top speed and increased cornering capability. Most of the form for the car came from mathematical computation with the help of Malcom Sayer. Initial tests on the unpainted prototype car, chassis XKC401, revealed a top speed of 178 mph, almost 30mph faster than the Type-C!

At the heart of the D-Type was an innovative chassis structure. It used stressed-skin engineering, incorporating the framework with riveted aluminum body panels to form a single rigid structure. Such design made the D-Type one of the first cars to use monocoque construction. As on the C-Type, both the front and rear panels of the car remained unstressed and easily removable for repairs.

The 1954 D-Type used a magnesium alloy for it’s body, framework and suspension. While this did keep weight down, it made production expensive and repairs even more expensive. By 1955 these materials were replaced by simple aluminum and steel counterparts.

The XK-based engine powering the D-Type played a large role in helping achieve a high top speed. It was both shorter, thanks to dry-sump lubrication, and more powerful than the previous engines. The combination of a revised block, larger valves and triple Weber carburetors helped the engine achieve 245 bhp.

Dunlop disc brakes were employed to all four wheels. Jaguar worked exclusively with Dunlop during the fifties to adapt aircraft disc brakes to road cars. In 1953 the first use of disc brakes was witnessed on the C-Type works cars. It was this potent feature that helped the C-Type achieve victory at the 1953 Lemans. Suspension of the D-Type type used double wishbones up front with a rigid axle in the rear. This was the familiar setup found on all production Jaguars during the period.

The Jaguar D-Type & Racing

As the Le Mans organizers, the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO), entered the initial phase of their ultimately complete embrace of pure racing cars, prototypes, Jaguar responded with the D-Type. Unlike its predecessor, the D was built solely for Le Mans, and beneath even sleeker Malcolm Sayer bodywork, the new car featured a central monocoque structure of aluminum, to the front of which attached tubular framework that carried the necessary ancillaries.

The venerable XK engine got a dry-sump lubrication system and a “wide-angle” cylinder head—helping raise output to 250 hp—then tilted over eight degrees from vertical to lower the hoodline. Aerodynamic drag was cut further by enclosing much of the undercarriage, and a vertical fin arose from the driver’s headrest to aid stability while reducing drag even more. The new car also had light alloy wheels, instead of the previous wire rims, to deal with the increased forces at work on the faster car.

Although some preliminary test runs were able to be made at various venues—including The Sarthe itself—the D Jags headed for the 24 Hours as brand-new cars of unproven design with minimal testing. The driver lineup remained largely unchanged, with Moss and Walker in one car (XKC403), and Rolt and Hamilton in the second (XKC402), while Peter Whitehead’s partner (in XKC052) was now Ken Wharton. Ecurie Francorchamps again entered XKC047, with Roger Laurent joined this time by Jacques Swaters.

Their opposition would not be as broad as before, as Alfa Romeo had retired from racing for the moment, Mercedes-Benz did not have its new car finished, Maserati’s transporter was apparently delayed, and Lancia decided to sit this one out. Ferrari, however, brought a full-force trio of 5-liter V-12-powered 375 Plus entries.

One, driven by Froilan Gonzales and Maurice Trintignant, prevailed on Sunday afternoon, once the three factory Jaguars were delayed by fuel filter problems amid reports of impurities in the fuel. Working to regain lost time, Moss was running 11th when he arrived at the end of Mulsanne in the middle of the night to discover he had no brakes! A supreme application of skill and an extensive escape road saved him from harm, but he drove carefully back to the pits where the car was soon retired. Whitehead and Wharton eventually got up to 2nd before being stopped by transmission troubles just before half time.

Although pelted by persistent rain, the remaining Rolt/Hamilton entry soldiered on, making its way up the order until only the Gonzales/Trintignant Ferrari remained ahead. There their advance stalled, though, as an incident with an errant Talbot bounced Rolt off the barriers at Arnage. Damage was minor, but time was lost checking it out and the “edge” had been lost. Still, victory became possible once again as the leading Ferrari refused to start after its final pit stop. Regulations governing the number of mechanics allowed to work on the car were apparently ignored while the Scuderia scrambled to get it going again, but no protest was lodged by Jaguar, which preferred to win on the track. The red car’s advantage at the flag was less than half a lap. The Belgian C-Type finished 4th, six laps behind the Cunningham C4-R of Bill Spear and Sherwood Johnston.

By the time the 1955 race rolled around, fuel system fixes aimed to correct the flaw that spoiled the D-Type’s debut, but that wasn’t the only area of improvement. There was a longer, more aerodynamic nose—carefully designed and tested to ensure proper airflow—and Harry Weslake produced a new cylinder head with larger valves that helped lift the XK six’s output to 275 hp.

Mercedes-Benz returned with a trio of impressive new 300SLRs for an international lineup that included Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss (fresh from his stunning victory with Denis Jenkinson in the Mille Miglia) in one car, Karl Kling and Andre Simon in a second, and Pierre Levegh and John Fitch in the third. A lightweight sports car version of their dominant Formula One machine, the 300SLRs featured a tubular chassis clothed in magnesium bodywork and powered by a 3-liter, 300 hp straight-eight engine with direct fuel injection and desmodromic valve actuation.

Jaguar responded with a quintet of the improved D-Types. Four were BRG factory cars for Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb (XKD505), Rolt and Hamilton (XKD506), Bill Spear and Phil Walters (XKD507), and Don Beauman and Norman Dewis (XKD508), while Ecurie Francorchamps fielded XKD503 in yellow for Johnny Claes and Jacques Swaters.

The early stages became a fierce triangular fight among Ferrari’s Eugenio Castelotti, Hawthorn in his Jaguar and Fangio in the Mercedes that resulted in 10 lowerings of the lap record before the race was two hours old. Although the 6-cylinder Ferrari 121LM began to fade with clutch problems, Fangio and Hawthorn carried unabated on as time came for the first pit stops after two and a half-hours.

As Hawthorn led Fangio onto the main straight, the Briton signaled his intention and turned right, toward his pit, cutting across the bow of Lance Macklin’s slower Austin-Healey 100S. Macklin swung back left in avoidance and Fangio somehow squeezed through undamaged, but the 50-year-old Levegh, going a lap down to the leaders, was not so lucky. His Mercedes smashed into the back of Macklin’s car at about 130 mph and was catapulted, disintegrating, into the vast crowd across from the pits. It was the greatest disaster in racing history as Levegh and more than 80 onlookers perished.

The unprecedented carnage forced some very difficult decisions to be made in a relatively short period of time. The first of these was to continue the race in order to allow rescue crews reasonable access to the accident site, a move history considers a wise one. Some time later another tough choice was made as team manager Alfred Neubauer withdrew the remaining Mercedes machines—running 1st and 3rd at the time—in respect for the fallen. At season’s end Mercedes-Benz would withdraw from the sport altogether.

With the silver cars removed from the equation, Hawthorn and Bueb took a somewhat hollow victory, which Jaguar declined to promote. Nothing like lost glory mattered at the moment; the very future of the sport hung in the balance.

Grands Prix in Spain, Germany and Switzerland were cancelled that summer, with the Swiss ultimately imposing a ban on the sport that remains.

France even invoked a temporary moratorium, but when the schedule for 1956 was published, Le Mans was again present, although on July 28-29 rather than its usual June date due to changes at the circuit. Among them were the demolition of the pit complex and its reconstruction farther back from the racing surface. The “signaling pits” were also relocated to the slowest part of the course, the exit of Mulsanne Corner.

The track wasn’t the only focus for changes. New regulations limited prototype engines to 2.5 liters, cut on-board fuel capacity to 28 gallons, extended the laps required between refuelings to 34, and prescribed full-width windscreens for all cars. Because Jaguar had produced a sufficient number of D-Types to qualify as production cars they avoided the displacement cut, and for the first time some of the 3.4-liter engines were fed by fuel injection rather than carburetors.

The driver lineup included defending winners Hawthorn and Bueb (XKD605), journalist/racer Paul Frère and Desmond Titterington (XKD603), and Jack Fairman and Ken Wharton (XKD602) in the three factory cars, with Ron Flockhart and Ninian Sanderson in an Ecurie Ecosse entry (XKD501) from Edinburgher David Murray, and Jacques Swaters and Freddy Rouselle in the Ecurie Francorchamps car (XKD573).

Their main opposition came from Ferrari, with a trio of 625 LMs for Olivier Gendebien and Maurice Trintignant, Phil Hill and Andre Simon, and Alfonso de Portago and Duncan Hamilton. Aston Martin had welcomed Stirling Moss once he was cut loose by Mercedes, and he joined Peter Collins in a DB3S, while Peter Walker and Roy Salvadori shared another, and Tony Brooks and Reg Parnell wheeled the first DBR1.

Almost immediately away from the start, Frère, Fairman and Portago tangled in the damp Esses and were out. Not an auspicious beginning for either team, and when the remaining works Jaguar was delayed by a cracked fuel-injection pipe, things didn’t look good for the lads from Coventry. The defending winners would only battle back up the order to 6th by the end, but all was not lost for Jaguar.

The squad from Scotland, Ecurie Ecosse, run for Murray by W.E. “Wilkie” Wilkinson, saved the proverbial bacon, as Flockhart and Sanderson outran the Moss/Collins Aston by a lap. The best Ferrari could do was a distant 3rd for Gendebien and Trintignant, and the Belgian D-type took 4th. The victory was Jaguar’s fourth in six years, adding another layer to the legend.

As it entered its 50th year as a club and celebrated the 25th running of its 24-hour race in 1957, the ACO relaxed the stern displacement limits for prototypes that had cost the race its usual place on the World Championship calendar. With that status restored, Ferrari and Maserati jumped in with four-cam, 4-liter V-12-powered 335S and 4.5-liter V-8 450S models, respectively.

Jaguar closed its factory racing effort after 1956, but readily continued to sell cars to privateers. Thus were five D-Types on the entry list for ’57, two in the metallic Flag Blue livery of Ecurie Ecosse for the pairings of Flockhart and Bueb (XKD606) and Ninian Sanderson and John Lawrence (XKD603), and one each from Equipe Los Amigos for Frenchmen Jean Lucas and Jean-Marie Brousellet (XKD513), Equipe National Belge for Paul Frère and Freddy Rouselle (XKD573), and Duncan Hamilton, for himself and American Masten Gregory (XKD601). The lead Scottish entry, which was fuel-injected, and Hamilton’s car both enjoyed the use of Jaguar’s new 3.8-liter version of the XK power plant that produced nearly 300 hp, but this was still about 100 shy of the new Italian engines.

Arrayed against them were: four factory Ferraris, a pair of the new 335S models as well as a 250 Testa Rossa and a 315S; a trio of Maseratis, a 450S Coupe, a 450S Spyder, and a 300S; and a quartet of Aston Martins including a pair of DBR1s, a single DBR2, and a lone DB3S.

As it turned out, the new cars didn’t last and by the end of the third hour Flockhart and Bueb led as they would to the end. The only Ferrari left took 5th, as the rest broke their engines. Maserati found its cars all parked by the seventh hour, and the Astons fared only marginally better. One DBR1 ran as high as 2nd, but crashed in the 11th hour, while the other and the DBR2 retired with gearbox trouble.

The D-Types swept under the checkered flag holding the first four places as well as 6th, the marque’s brightest showing ever.

For 1958, the FIA mimicked the ACO’s post-1955 displacement cuts, imposing a three-liter limit on the full championship. This meant that Jaguar’s successful 3.4-liter six was no longer eligible, and though a destroked three-liter version was developed, it never proved reliable. Nevertheless, five

D-Types carried Coventry’s flag at Le Mans, two from Ecurie Ecosse (XKD504 and XKD603), and one each from Duncan Hamilton (XKD601), Henri Peignaux (XKD513), and Maurice Charles (XKD502). They were supplemented by two of Brian Lister’s Lister-Jags, but only one of them would see the finish, driven into 15th place by Bruce Halford and Brian Naylor. Engine woes and accidents consumed the rest, and sadly, Jean-Marie Brousselet was killed when he spun the Peignaux D-Type into the path of Bruce Kessler’s Ferrari leaving the Dunlop Bridge. In the end, Phil Hill and Olivier Gendebien won for Ferrari.

The story in 1959 was little different, as the four Jaguars entered—a D-Type from Ecurie Ecosse (XKD603), two Listers and a Tojeiro-Jag—all retired with engine failures. Aston Martin swept the top two spots, Carroll Shelby and Roy Salvadori sharing the winning DBR1.

Ecurie Ecosse entered one of its D-Types (XKD606) in 1960, but its crankshaft broke at about half distance. This would be the last Le Mans for the D-Type, but it had served admirably, scoring three wins in four years at the height of its glory.

"It was the most aerodynamic car we'd seen up to that time… a hell of a motorcar."

Stirling Moss