The Grand Prix Alfa Romeo: Alfetta 158/159

As a long-term Alfa “person,” I have never had any problems when it comes to the inevitable discussion of the best Alfa Romeo of all time or, for that matter, the Alfa one would most like to drive if the opportunity ever arose. The answer for me—and I’m sure many other Alfisti—was always the same…the 158/159 Alfetta. Not only was the Alfetta so successful, it was also fantastically charismatic and elegant. It was…and is…the ultimate Alfa Romeo.

Background

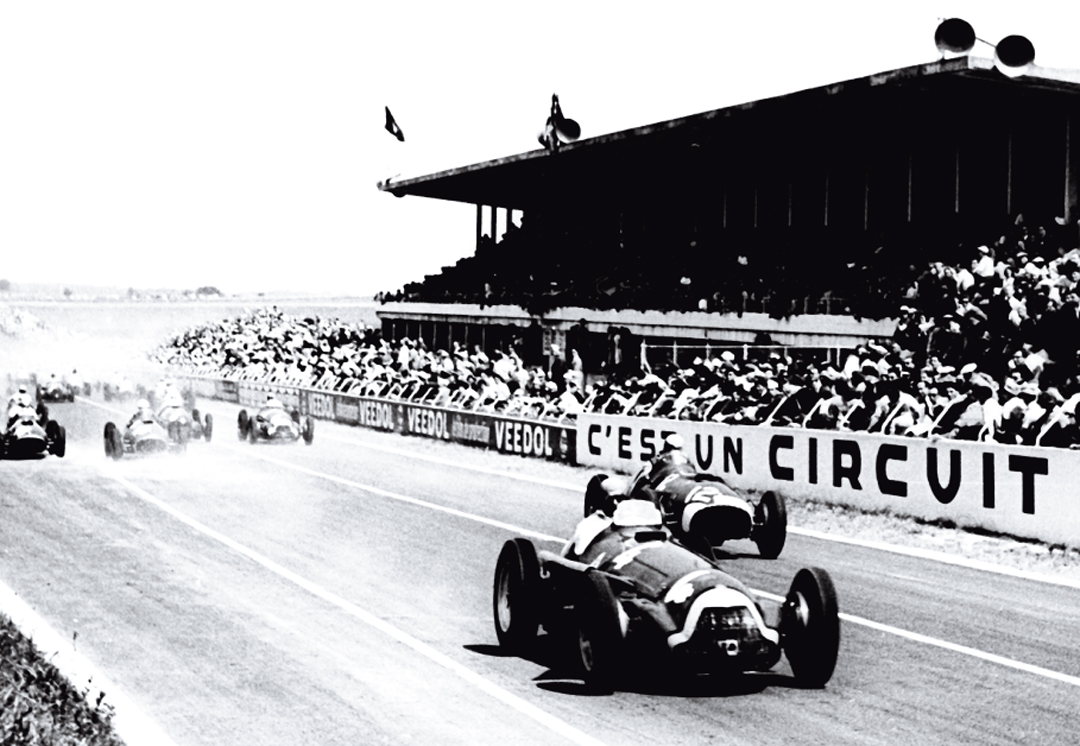

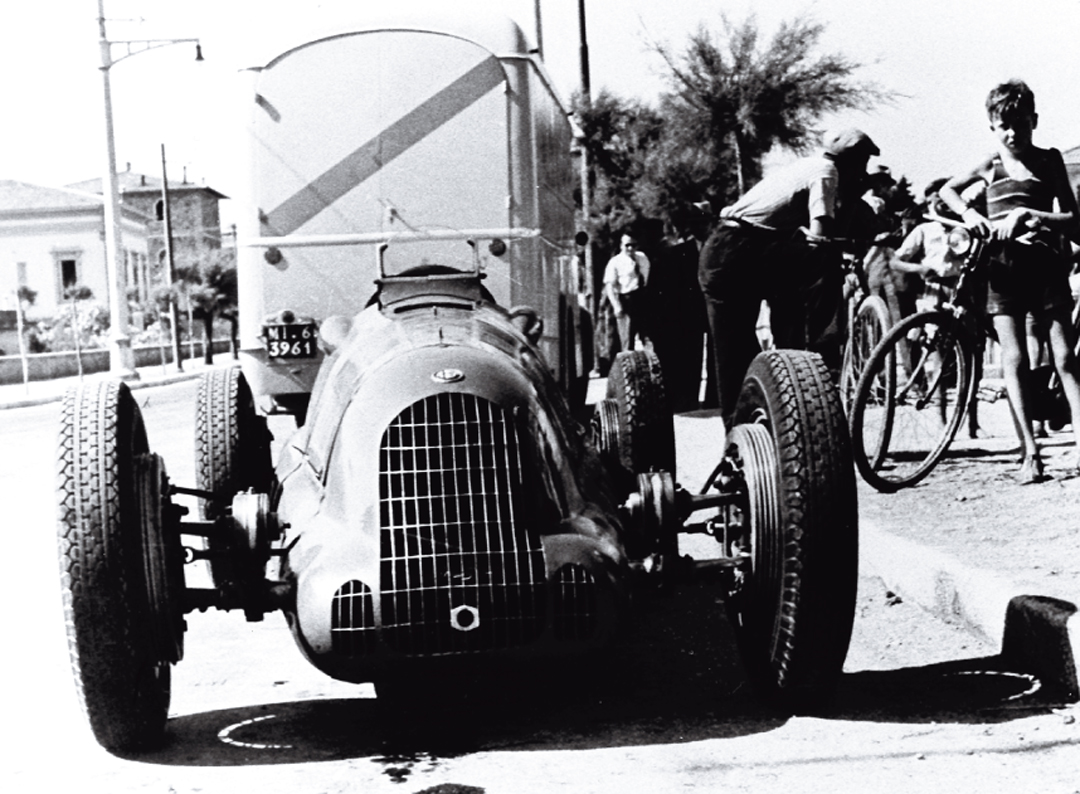

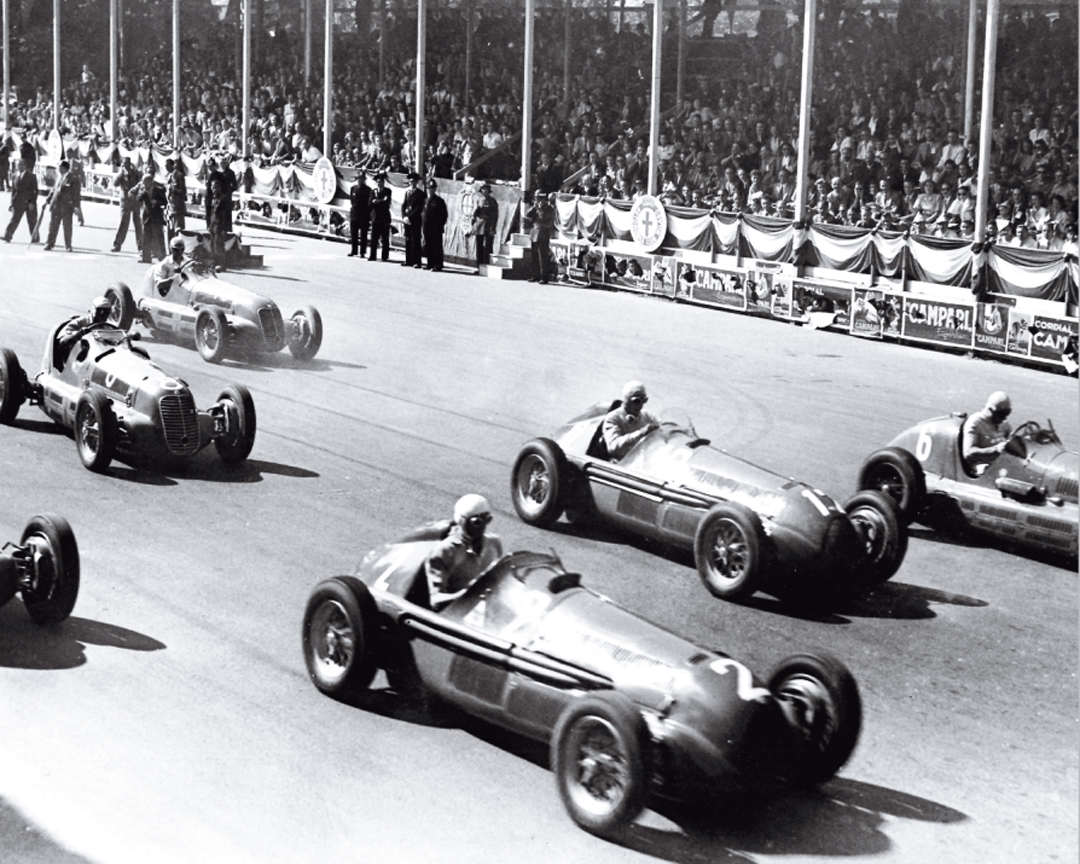

The 158 first appeared in 1938 and promptly won its first race, the Coppa Ciano Junior race at Livorno, in the hands of Emilio Villoresi. There is a marvelous symmetry to the fact that it also won its last race (as the 159) in 1951 (Fangio in the Spanish GP) and along the way claimed two World Championships in 1950 and 1951. However, if the World Championship had been instituted immediately after the war it would have won more. The Alfetta, as it came to be known, won 11 out of 11 races in 1950, when Dr. Nino Farina became the very first official World Champion and it gave Juan Manuel Fangio his first World Championship the following year. The Alfetta did not suffer a major defeat from 1939 until the British Grand Prix of 1951, winning a very long string of consecutive races. One would obviously have to set up some pretty tight criteria by which to judge the “greatest GP car of all time” but on any criteria, the Alfetta is always going to be up near the top of the list.

Photo: Peter Collins

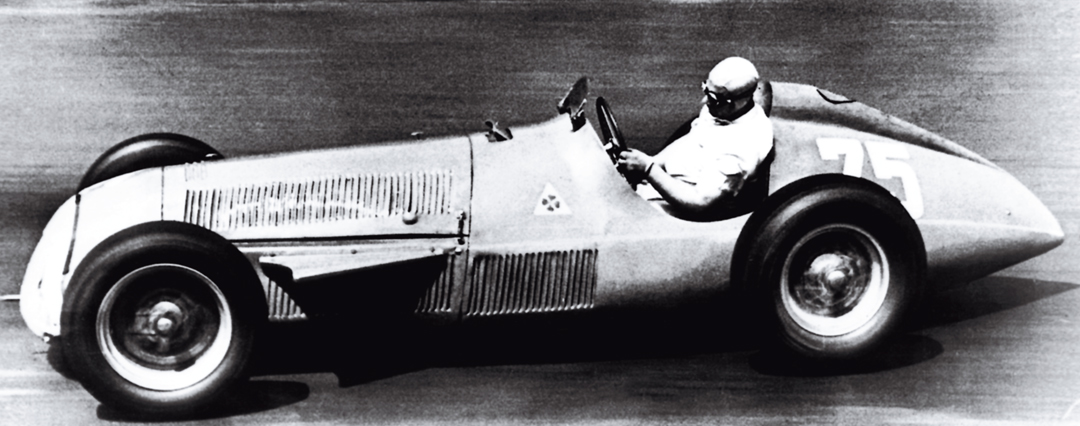

The car which started as the 158 was rapidly dubbed— according to the best sources in 1938—the Alfetta, or “little Alfa.” This moniker arose both because it wasn’t a full Grand Prix car to start with and because it was actually a physically small machine in a period when important racecars were large—even titanic—such as the Auto Unions and Mercedes of the pre-war period. Originally built to contest voiturette races rather than full Grand Prix events before the war, when the Grand Prix regulations changed to incorporate the 1.5-liter formula the Alfetta was promoted to the “big leagues”, though by then its diminutive nickname had stuck. It is interesting, in retrospect, that English-language journals of the time didn’t pick up the Italian-sounding Alfetta name and instead called the car the “Alfette.” “Motor Sport” in England did this up until 1947. It rarely referred to it as the 158, simply using the term “Alfa’s 1.5-liter car.”

Designer Gioachino Colombo worked for Alfa Romeo and Scuderia Ferrari, who were running the factory Alfa Romeos from Modena, and had been doing so throughout the 1930s. Vittorio Jano, under whose supervision Colombo worked, probably overshadowed Colombo through much of his career, but the design of the 158 was all Colombo’s. Throughout the mid-’30s, German supremacy in motor racing put an end to Alfa’s glorious days with the P3. Jano’s response was a 3-liter V-16 (no, BRM weren’t the first!) but this car was not a success, and in a period of serious political intrigue in Italian racing, it heralded the departure of Jano. While Jano had been supremely important in the earlier days of Alfa Romeo, there were others who were able to make an equal contribution. Fortunately, during this same period, Colombo developed the brief to design a car to contest the voiturette class for 1.5-liter cars, thus giving Alfa Romeo a chance to win the Italian National Championship. Beginning in 1939, all former Grand Prix events in Italy were run to the 1.5-liter rules but no one particularly thought this formula would stick for years to come, considering the impending war. The Italians, however, had a long custom of creating new racing classes, especially when a change of rules could bring greater success to Italian teams.

Photo: Peter Collins

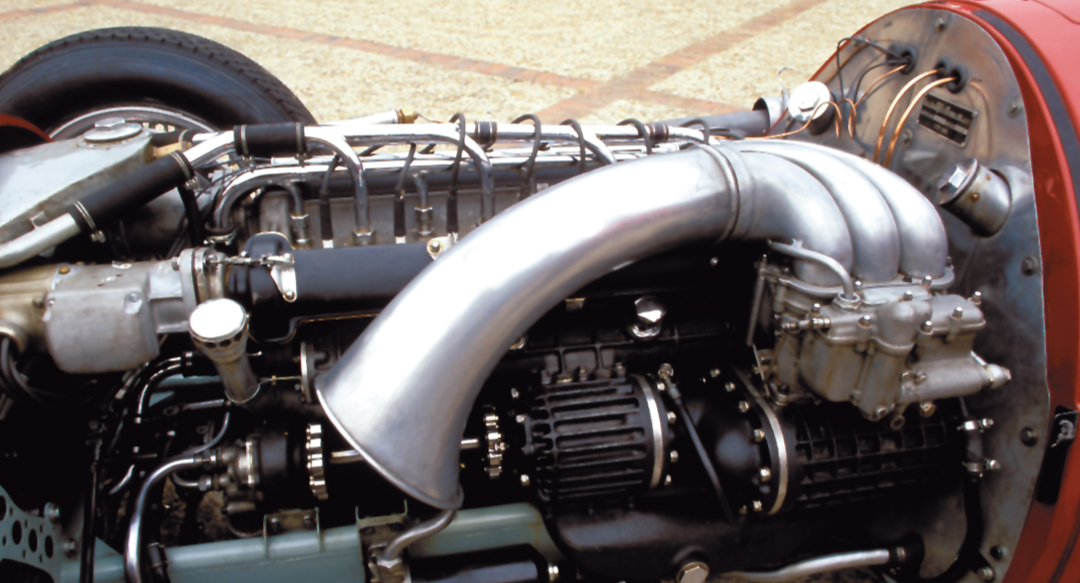

The straight-eight, single-stage supercharged 158 made its debut in the voiturette race accompanying the Coppa Ciano in August, 1938. At the time, voiturette racing was the equivalent of F2 or today’s F3000, but up to that point it had been the realm of Maseratis and ERAs. However, three new 158s turned out for the Coppa Ciano to be driven by Emilio Villoresi, Clemente Biondetti and Franco Severi. At the checkered flag, Villoresi and Biondetti finished 1st and 2nd giving the Alfetta its first win in its maiden outing. While the 158 did encounter some teething troubles in its early races, the car’s development was ongoing and continuous. The engine started by producing 195 bhp at 7,000 rpm but by the end of its 13-year life it was managing a useable 420 bhp at 9,000 rpm, and on occasions could produce 450 bhp from its original 1.5 liters of displacement!

The 158 hit its stride and won numerous races before the war, though it lost one very notably when it had every reason to believe it was going to score its biggest victory to date. This all came about in the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix. Prior to the Tripoli Grand Prix, Alfa’s racing program was still in the hands of Scuderia Ferrari, though it was soon to be transferred back to Alfa Romeo itself. Enzo Ferrari had been pushing Colombo to refine and improve the 158. The result was the updated 158B for Tripoli, the latest development car which would have been the machine used on into the early 1940s had the war not interceded. The plan was that the Alfas were going to go to Tripoli and dominate what was thought to be the last big race before the war. Europe was on the brink, and Mussolini was continuously trying not to fall off the fence into one camp or another. When he finally fell on the side of Hitler, he saw the propaganda potential in blessing an Italian team in Tripoli which would win and put him on a level with Herr Hitler. Both Hitler and Mussolini were very fond of the big names in their respective motor industries and both used racing as a means of demonstrating not only national superiority but also their personal wisdom and power as leaders. Mussolini was always looking for a way of getting one up on the German Führer and saw the 1939 Tripoli race as a great opportunity. However, imagine Il Duce’s chagrin when Mercedes created virtually overnight…well, in eight months…a 1.5-liter car, the W165. The Germans had read the Italian intentions and were not going to be beaten by the upstart Italians. So important did this propaganda battle become that the Mercedes factory worked behind barbed wire, in utmost secrecy, to finish the W165.

In the race, the Alfas suffered from overheating and could not keep up with the silver Mercedes. Wifredo Ricart, who became responsible for the Alfa racing department, had taken advice from an Englishman named Harry Ricardo, whose engineering skills were well known. He had recommended certain changes to the cooling system that went unheeded. The factions at Alfa which disliked Ricart, a Spaniard, were vindictive and blamed him for the failure, and it appears he passed on the blame to Tripoli team manager Meo Constantini, who had reduced the water pressure, leading to the overheating and failure. It was an example of the politics of the period, set against a backdrop of fierce nationalism.

However in 1940, the 158 avenged the previous year’s defeat by winning that year’s Tripoli event, though by then the war was on and Mercedes was absent. Italian pride was bolstered by the fact that Farina won at a faster pace than the Mercedes had managed in 1939, a clear sign of the furious pace of development at the time. What followed next was the romantic story which has become part of Alfa myth and legend, of how many of Alfa’s racing cars were secretly moved from the garages under the Monza banking to a cheese factory in Melzo, further north. The story is at least partly true, in that the owner of the cheese factory had several other factories and did business with Alfa Romeo, and it wasn’t surprising that a “friend” should be asked to hide some cars from the Germans. The Alfas were scattered about to hide them from the troops around Milan, and that indeed kept them safe until after the war.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

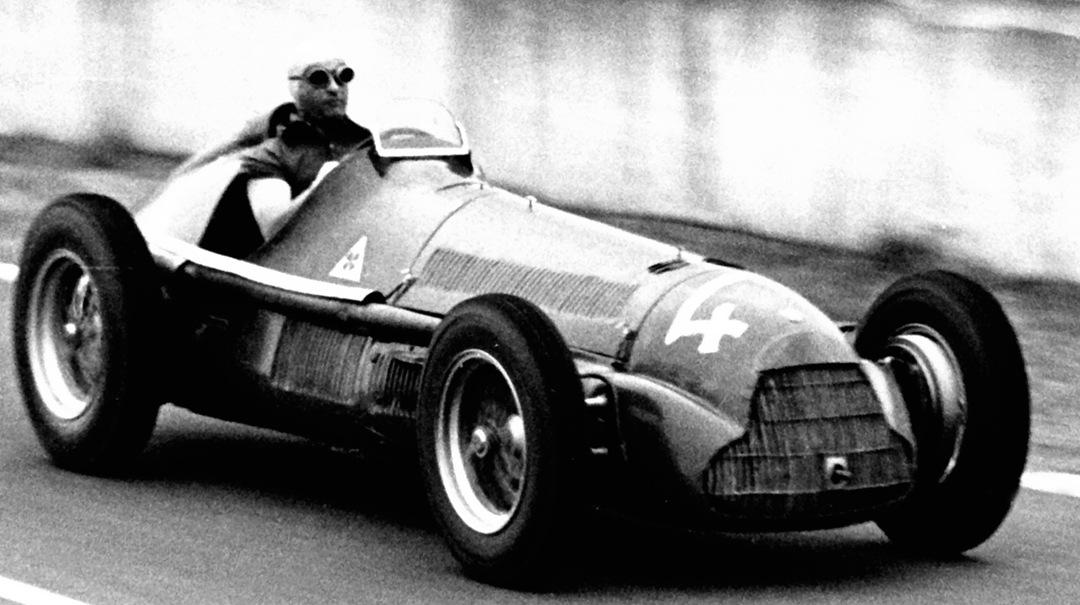

The 158 stormed back into action after the war, commencing a long winning streak, and when the World Championship was instituted in 1950, the 158 won it with Giuseppi “Nino” Farina driving. By the end of 1950, there were enough modifications and improvements to the car to consider it a different model, and thus it became known as the 159. Major improvements were made to the brakes, while experiments were tried with a de Dion axle. In the engine department, the cars now benefited from a two-stage supercharger, providing another serious boost in power. Some historians argue that the difference between a 158 and a 159 was the presence of these two-stage superchargers, but that is inaccurate, as they were in fact tried much earlier. For the 1951 season, inaugural World Champion Farina was teamed up with Juan Manuel Fangio, Felice Bonetto and Luigi Fagioli, among others, to drive the 159. Farina won the Belgian Grand Prix, while Fagioli claimed the French, but Fangio won the Swiss and Spanish Grands Prix and racked up enough points over the eight-race sea- son to claim his first World Championship and Alfa’s second Manufacturers. Sadly, at the end of the 1951 season, Alfa Romeo retired from Grand Prix racing and a magnificent segment of Grand Prix history came to an end.

A 158 Escapes from Alfa Romeo

At the Italian Grand Prix held at Monza in 1951 (just before the retirement of the Alfa Romeo team from racing) a spectator named Mike Sparken was thoroughly taken by the sound and glory of the Alfetta. He later went on to race for Gordini, took part in the British Grand Prix and had a long sports car career. He also owned a number of important Alfa Romeos over a considerable period of time, perhaps the most important being the 1938 Le Mans 2900B coupe. But in the 1980s, Sparken and his wife, Carol Spagg, started a quest to realize a long-held ambition to own one of the Grand Prix Alfettas.

They knew through their contacts with Alfa’s Luigi Fusi that there were three surviving 158s, and two 159s. The 159s were in Alfa’s museum at Arese with one of the 158s, while the second 158 was in the Biscaretti Museum in Turin. However, Fusi also said that Alfa had a third 158 in the “crypt,” the old underground storage area at Alfa’s now-defunct Portello factory. To cut a very long story short, they went to Alfa Romeo and asked if they could see and buy the remaining 158. Much negotiation ensued, but eventually they were able to convince the factory to trade the Le Mans coupe for the 158. Once back in England, Jim Stokes restored the 158’s mechanics, and Paul Grist the body, substantial parts of which survived and are still part of the car. Ultimately, the car returned to Monza for an emotional reunion with former drivers, the late Luigi Villoresi, Baron de Graffenreid, and post-war team manager, the late Gianbatista Guidotti. The 158 then appeared in a demonstration at a VSCC Silverstone meeting, and after a few years of ownership, it was sold to collector Carlos Monteverde, who ran it for Willie Green at Silverstone and Goodwood. More recently, the car passed to Carlo Vogele, who competes with it himself.

There’s an interesting historical side note to be injected into the above account. In the run-up to that 1951 Italian Grand Prix, Stirling Moss was at Monza several times to test the BRM V-16. He was there on one occasion when Fangio was testing the Alfetta and went over to watch. Guidotti spotted him, and on October 6, Moss was given the chance for a few laps in the car. Oddly, this later led to an offer of a drive, though at a time when it seemed certain that the cars would not race again.

Driving a Piece of History

Back in 1997, well-known historic car restorer Tony Merrick brought along three important cars to the remains of the Brooklands race circuit for a very small group of journalists (well, two actually) to sample: the Maserati 8CL, Ferrari 555 Supersqualo, and the Alfetta 158/159. The test was limited to a few very short runs on the old banking for photos only. It was fantastic to be near those cars, but I was left with the feeling of a job unfinished. I knew that one day I needed to really get to grips with the Alfa.

Recently, while working on a book on the Alfetta, I became aware of just how few really good color photos of the Alfa ever appeared. As a result, I came up with the unlikely idea that we should do our own color work, presenting something new and in detail, and in the bargain do a proper test of the car and give some space to its own amazing history.

Well, Tony Merrick and GTO Engineering came through again, and shortly before this year’s Goodwood Revival, the Alfetta was delivered to our test venue for a thorough exploration of this immensely rare and technically wonderful Grand Prix machine. Carlo Vogele, now the owner of the only Alfetta in private hands, was not surprisingly cautious and reserved about the idea, as the car was about to be raced at Goodwood, and it was clear that he treasured it beyond its financial worth. Very, very few people have ever had the opportunity to drive any Alfetta, and this particular car is especially unique in that it’s still racing…seriously. I knew I was about to be a lucky boy indeed.

The GTO Engineering transporter doors were opened and the 158 was rolled out. Actually, it is more accurate to call this car a 158/159. It carries a 158 chassis number and a 159 engine. It was a 1951 specification car, a 158 chassis upgraded from original 158 specifications to 1951 standards with the improved, more powerful engine and current bodywork, though it does not have the 1951 experimental de Dion axle, which was not fitted to all cars. It also doesn’t have the later, wider 159 fuel tanks required by the car’s huge fuel consumption, although signs exist on the chassis that it may have once carried these tanks at some point. This seems likely to have been one of the cars raced in the Swiss or French GPs of 1951, and thus may have been driven by either Fangio, Fagioli, de Graffenreid, Sanesi or Farina. That part of the heritage of this and all the other surviving 158/159 cars is still being unraveled, though it is important to state that the chassis remained essentially unchanged in any dramatic way throughout its history, whereas there was constant improvement to the engine, and the engine in this car is very much the last word in that development.

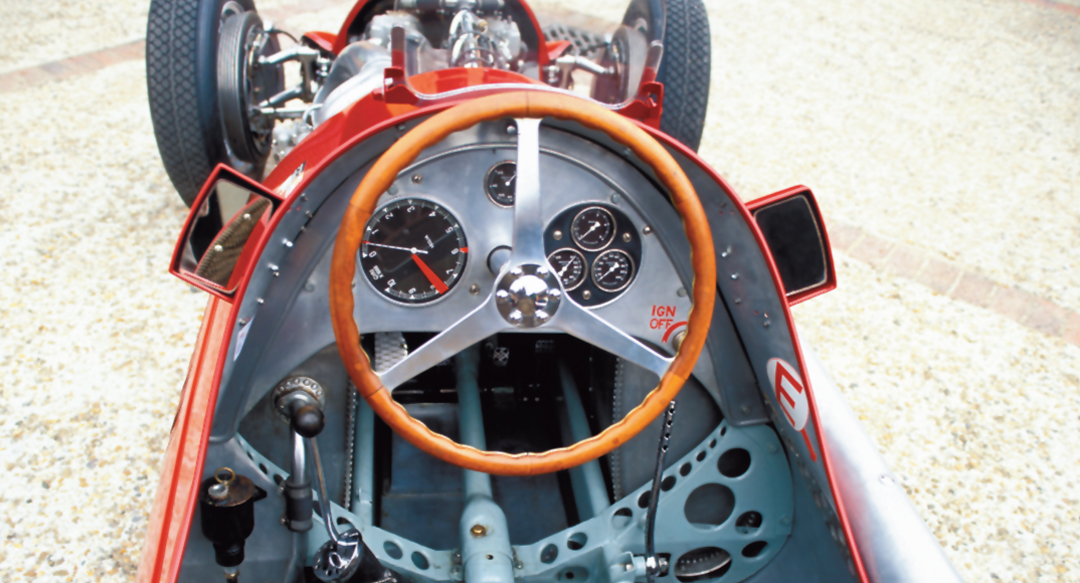

So here I was finally ensconced in all that incredible history. Sitting in the corduroy seat—which was missing when the car was found, as were some other fairly minor parts—I discovered the rearview mirrors, which had been inside the cockpit on my first acquaintance, were now fared into the outside of the body. The key areas to remember with this car are that it has a central throttle with the brake on the right. The gear change, which is also on the right, is “reversed,” that is, first is to the right and forward, back for second, towards you and forward for third, and back for fourth. Another salient point I soon learned was not to lean on the exhaust, which is situated right next to your right arm!

The spacious cockpit made this a comfortable place to work. The hydraulic starter banged the engine into life with no trouble, and Simon Bish, who has now looked after this car for 10 years and knows it extremely well, decided the plugs were clean enough not to need changing. In fact, the engine was so well tuned that it started instantly. No throttle is used to start, though a bit of revving kept it alive until sufficiently warm. The clutch is user friendly and I was soon away in first gear with that fantastic sound belching out of the exhaust behind my right ear, the clatter of valve gear and supercharger whining away in front, and then it all blended into one smooth concerto as the revs went up and the car gained momentum. Some people have said the Alfetta of today doesn’t quite have the boom of yesteryear. I don’t know if that is nostalgia’s deafness, but it sure sounded good to me.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

The GTO crew were trying 18in. tires on the front for the first time, as the car usually uses 17in. rubber (7.00/7-18 Dunlop Racing on the rear and 5.50/6-18 on the front) which they predicted Willie Green might not like as much as the smaller ones at Goodwood. The difference was, of course, not apparent to me at my somewhat restricted pace. What was abundantly evident was the enormous torque this car has across the rev range. A stab at the central throttle even at low speed gives the car a considerable shove, and once I was away and moving in 4th it was much the same at higher speeds. The test track we used is a high-speed venue, bearing a resemblance to the old Monza, and the series of flat-out left-hand bends especially suited the 158/159. Past the “pit exit” there is a left-hander with a mild banking which the car just stuck to as the revs rose in third and it propelled itself off onto the first straight, rushing up to the only slow right/left downhill combination. From there on there were a series of very quick left sweeps back to the main straight.

The steering is markedly light and as a result the car moved about on the bumpy surface but was totally controllable. After some laps, these sweeps are all flat in top, though this was at my self-imposed 6,000-rpm rev limit. What must have it been like at 9,000!? Recently I asked Moss about his impressions of the car when he tested it at Monza. After consulting his diary, it was clear he was fairly noncommittal about the car at the time. His diary recounts how “brakes seemed bad, but the road-holding good and very steady.” He commented that the BRM seemed a lot heavier in comparison, but that the BRM disc brakes were better. With the benefit of hindsight, Moss says it was clear the Alfa was a superb car, even though it was at the end of its career. I have to admit that I didn’t test the braking system to the degree that it was done in period testing and races, and as it is in current historic events. What was clear to me, however, was that the Alfetta remains perfectly balanced under braking into the medium-fast and fast corners on our test circuit, and presented no problem where heavier braking was required. With the exquisite handling and balance, the outstanding torque can then be maximized as the car is on the gas early in the corner and the revs remain high on exit. This saves unnecessary gear-changing, and that preserves the car’s life and makes it an “easy” car to drive.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

The thrill in driving this car is feeling that acceleration course through you, from your backside and fingertips, as the supercharger’s whine pierces the eardrums.

After a number of gradually quicker laps, the corners leveled out and the Alfetta flicked quickly through both the fast and the slow bends. The engine pulls and pulls and the challenge was to see how close you could get to what that beast was capable of. Sadly, it was about to go racing so there was a limit to meeting that challenge, but the car told the driver something very precise about what those days might have been like…just a taste, but a taste that would last. The fact that we went through quite a supply of methanol as the learning was taking place…at about 1.5 miles to the gallon…was testimony to just one of the technical challenges the Alfa engineers faced all those years ago. But for me, history had truly come alive…what a great experience.

Buying & Owning an Alfetta 158

Better stick to a late model Alfetta GTV! This, as we have said, is the only such car in private hands, and Alfa Romeo is unlikely to ever part with the others, even for the alleged $10 million dollars that is bandied about. Even if you did convince Mr. Vogele or Alfa Romeo to accept your lottery winnings, you would need to employ a team to look after it, because the knowledge of running such an over-engineered racecar is very thin on the ground. When the Alfetta engine gets taken down, there’s old history in there, and you need to make new parts to replace the old ones. I understand that the last batch of original spares is just about gone now!

Specifications

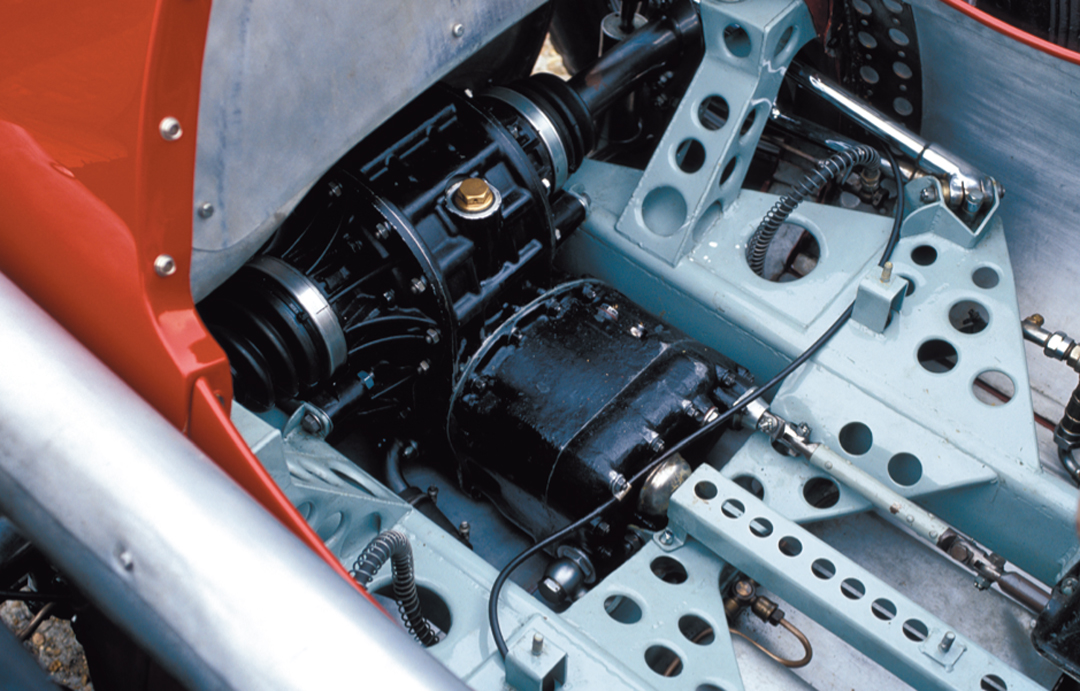

Chassis: Tubular frame with two main members linked by four cross members, engine, and final drive in unit

Suspension: Front: Trailing arms and transverse leaf spring. Rear: Swing axles with transverse leaf spring

Wheelbase: 2,500 mm

Weight: 1,364 lbs

Engine: Eight cylinders in line with twin overhead camshafts gear-driven from the front of the crankshaft

Bore and Stroke: 58mm x 70mm

Capacity: 1479 cc

Valves: Two valves per cylinder

Compression Ratio: 6.5 : 1

Supercharger: Rootes-type two stage, total boost 42.6 psi with Weber carb

Power: 425 bhp at 9,300 rpm

Transmission: Multi-plate dry clutch; gear box in unit with the final drive; four forward speeds and reverse

Brakes: Hydraulically operated drums mounted outboard; 14.8in. diameter front, 13.8in. diameter rear

Wheels: Borrani wire spoke center-lock

Tires: Front: 700 x 18. Rear: 600 x 18, maximum speed: 190 mph

Resources

Hodges, D.

The Alfa Romeo Type 158/159 1966

Profile Publication, Surrey, England

Venables, D.

First Among Champions—The Alfa Romeo Grand Prix Cars 2000 Haynes Publishing,

Somerset, England.

ISBN: 1-85960-631-8

Thanks to Carlo Vogele, Tony Merrick, Simon Bish & GTO Engineering.