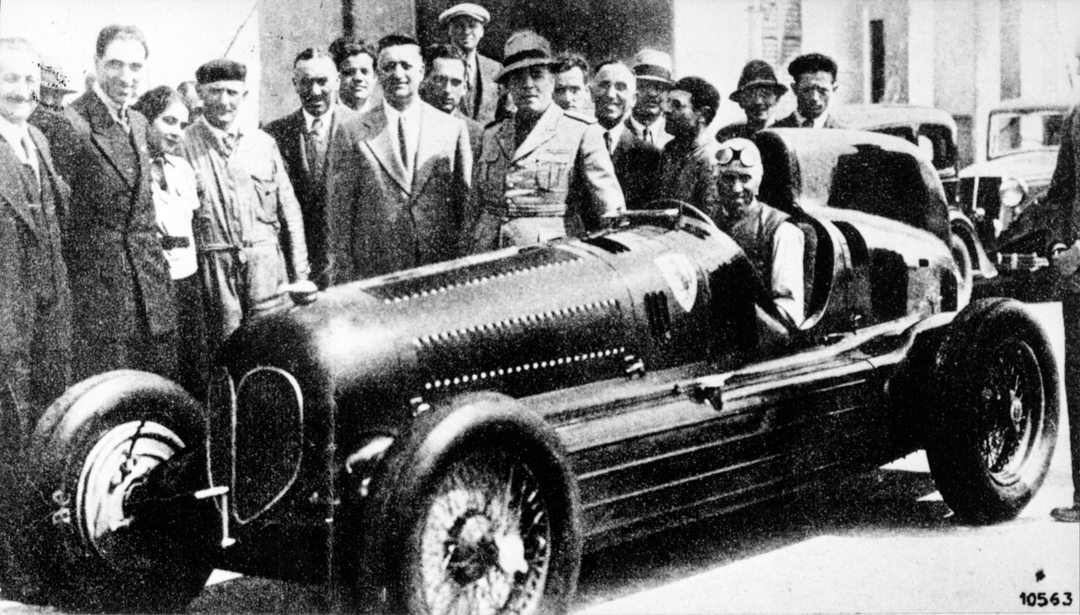

It wasn’t Alfa Romeo’s first twin-engined car; in fact it wasn’t really an Alfa Romeo at all. It was, arguably, the first Ferrari. Because the 1935 Bimotore was designed and built at Enzo Ferrari’s behest in Modena by the great Luigi Bazzi a few months after the Scuderia assumed Alfa Romeo’s motor racing responsibility.

The Vittorio Jano-designed 1931 Alfa Tipo A had two 1750-cc engines side-by-side. Luigi Arcangeli crashed one of them and killed himself while practicing at Monza for the 1931 Italian Grand Prix, after which the remaining three Tipo As were withdrawn. The Bimotore of four years later had its two engines fore and aft and carried Ferrari’s Prancing Horse badges, rather than the Alfa Romeo crest.

The 1935 car was supposed to be the German beater, the one that took the rampaging Mercedes-Benz W25s and Auto Union Type Bs to the cleaners. It had the power, oceans of it at 540 hp, while the Mercedes generated 430 hp and the AUs 375 hp. So it looked like the once-dominant Alfa Romeo and Scuderia Ferrari were onto something.

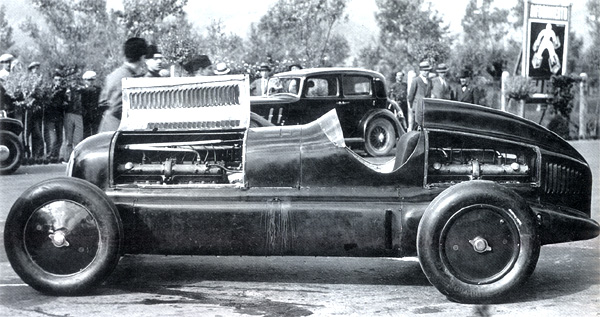

The ingenious Bazzi had four months in which to design and build two Bimotores. One was given a brace of the latest 8-cylinder, 3165-cc P3 engines and the other the older P3 2905-cc units. One engine was in the front and the other in the back in each case, with V-form drive-shafts. The rear engine was connected to the single 3-speed transmission by a longitudinal shaft. Of course, the connection between the two engines was not full-time; instead, there was a joint upstream from the transmission that brought the second engine into play and put it back to sleep again when not needed. Each power unit had its own crank handle.

The chassis was a modified version of the mythical P3’s, suspension was independent all round, the brakes hydraulic drum with a hand brake for the rear axle. This remarkable concoction could turn out a top speed of over 325 kph, or more than 200 mph. But it was heavy. The Mercedes and AUs toed the line of the Grand Prix 750-kilogram weight limit, but the Bimotore weighed in at a massive 1300 kg, almost double the legal limit, so it could only race in formula libre events, like the Tripoli Grand Prix or the Avusrennen.

Its big problem was that it swerved wildly. It couldn’t keep a straight line and it handled like a pig. The Italian mechanics called it il cavallo pazzo or crazy horse.

It took all of Tazio Nuvolari’s incredible talent to stop the thing from charging into the countryside as he tested the first of the cars on the Brescia-Bergamo road. And even at that early stage the Bimotore was going through its tires like there was no tomorrow.

Still, in May 1935 two of these wild and wooly cars showed up at the Grand Prix of Tripoli, although Ferrari played safe and entered four P3s as well. The Mellaha circuit boasted the long straights for which the new car was designed, so there was guarded optimism in the Ferrari camp. But qualifying turned out to be a major disappointment, causing faces to drop as the best Tazio could do was put his bigger-engined Bimotore halfway up the grid, with Louis Chiron in the slightly less powerful twin-engined car on the last row.

The race was to be run over 40 laps in sweltering heat, not exactly ideal conditions for a car that ate its tires. Sure enough, Nuvolari pitted for a tire change after just three laps. Three-quarters of the way through the event with 10 more laps to go, Tazio was 4th and was creeping up on leader Varzi’s Auto Union, but even his car was shredding tires. As Achille pitted, Nuvolari briefly moved into 2nd place until he was caught by eventual winner Rudolf Caracciola and his Mercedes W25B. Varzi managed 2nd, Luigi Fagioli 3rd, Nuvolari 4th and Chiron 5th. True to his prediction, Tazio’s Bimotore chewed up no fewer than 13 tires!

It was Chiron who produced the Bimotore’s best racing result with 2nd at the 1935 Avusrennen on the five-mile banked autobahn circuit just outside Berlin. The race was run in three five lap stints—two qualifiers and the race itself—to minimize tire shredding. This time, Nuvolari stopped for new tires after just two laps, and did so again before the event was over, all that to come 6th in his crazy car. Chiron managed 2nd overall in the race itself, having learnt how to nurse his tires at least a little in that impossible car.

Embarrassed by the Bimotore’s lack of racing success, Enzo Ferrari turned to land speed records, very much in vogue in the ’30s. He intended to better a series of international Class B times set by Frenchman Michel Doré driving a Panhard that produced an average speed of 137.643 mph.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

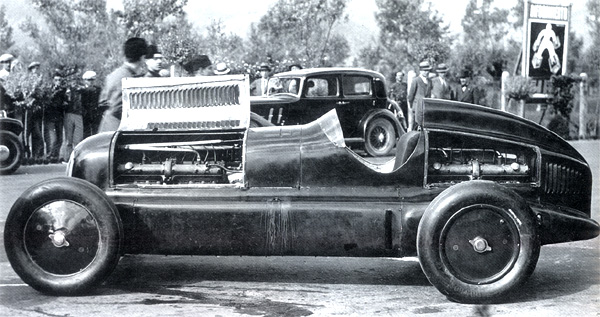

At dawn on June 15, the tips of the Tuscan cypress trees swayed to and fro in a stiff breeze that rolled across the Lucca-Altopascio section of the Florence-Coast motorway as the more powerful of the two Bimotores was readied for an attempt on Doré’s record by Nuvolari. Not a good sign, because the ultra-heavy, ultra-powerful Alfa-Ferrari was already skittish, so it would be even worse in a strong wind.

When Tazio started his first run, the Bimotore oscillated as the wind hit it from the side, threatening to make it charge into the countryside like a mad thing. Nuvolari used all his talent and sensitivity to bring the wallowing car to heel and raced on to set an outward flying kilometer record of a massive 205.267 mph and a return of 194.796 mph, to produce a new record average of 199.768 mph. His record flying mile average was 200.823 mph, another record.

For his bravery in succeeding against such odds, Nuvolari was awarded Italy’s Gold Medal for Valor.

Ferrari made one last stab at racing honors by entering a Bimotore for Nuvolari in the Grand Prix of France at Montlhéry. The little Mantuan led the race for the first 15 laps, until he had to retire ignominiously with transmission trouble.

After that, the Bimotores began to gather dust in Scuderia Ferrari’s Modena warehouse and stayed there until Ferrari disposed of them.

Ironically, the Bimotore in the Alfa Romeo museum at Arese in northern Italy is a replica, built with some original parts. But there is a British Bimotore of sorts, called the Alfa-Aitken, which has been knocking around the world for half a century or more and is now believed to be somewhere in Austria.

It happened more or less like this. Briton Arthur Dobson travelled to Modena and offered to buy one of the Bimotores, which were in bits at Scuderia Ferrari. So the Commendatore gave orders that one of the cars be rebuilt and the deal was done. Dobson took the car back to the UK and raced it, before selling it to the Hon. Patrick Aitken in 1938. He had the rear engine taken out and the chassis shortened. After the Second World War, Tony Rolt bought the Alfa-Aitken and had its cubic capacity increased to 3.4-liters. He drove the chopped-about car into 2nd place in the 1948 Grand Prix of Holland, the first to be held at Zandvoort.

After that, the Bimotore passed from owner to owner until it was sold to John McMillan in New Zealand in 1954, but he only wanted the engine so he sold the rest of the car to one Frank Shuter. The car eventually ended up with Murray Ditford in Dunedin, who, of all things, installed a GMC truck engine in it, after which it was sold to Gavin Bain of Christchurch. That’s where its savior, Tom Wheatcroft, found the battered, cannibalized remains of the Bimotore and he gave a Ford F3L sports racer in trade for the emasculated car.

Wheatcroft had the car fully restored, complete with engines front and rear and Ferrari badging. After being displayed as part of the world famous Donington Collection, the car seems to have ended up in Austria.