The story of the Alfa Romeo 158 is packed with heroes, starting with its designer, Gioacchino Colombo. He submitted his drawings for a straight-8 1,500-cc voiturette to the Alfa headquarters near Milan back in January 1936. And as the design began to take shape, Alfa placed on standby drivers like Tazio Nuvolari, Emilio Villoresi—Gigi’s brother—Giuseppe Farina, Raymond Sommer, Jean-Pierre Wimille, Clemente Biondetti, and their own staffer Francesco Severi to help whip the car into shape.

Three of the six 158s built by midsummer 1938 had their first outing in the Coppa Ciano Junior at Livorno on August 7, entrusted to Severi, Biondetti, and Villoresi. It was Emilio who scored the car’s first victory there and then, and Juan Manuel Fangio its last in 159 style at the 1951 Grand Prix of Spain at Pedralbes. The Alfa Romeo 158/9 had basked in glory for no fewer than nine years, a record that has never been broken by any other car.

But 1950 has to be the Alfetta’s greatest season: Giuseppe Farina became the first man ever to win the brand-spanking-new Formula One World Championship for drivers, and he did it in an Alfa Romeo 158.

It was ex-gentleman racer Count Antonio Brivio, the president of the Italian motor sport governing body CSAI, who first floated the idea of a Formula One World Championship for drivers back in 1949. His proposal was welcomed and actioned immediately by the Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile, which staged its new championship for the first time in 1950. Drivers were to battle for points in the Grands Prix of Great Britain, Monaco, Switzerland, Belgium, France, and Italy, and the one with the most points would win the title.

Rumors had been circulating for months that Alfa Romeo would make a comeback to Grand Prix racing in 1950, if for no other reason than to lay claim to the prestigious new world crown. They had not raced their super-successful 158s at all in 1949 for financial reasons and because their three key drivers, Achille Varzi, Count Carlo Felice Trossi, and Jean-Pierre Wimille, had all died in crashes or through illness. Their dominance, Alfa believed, was still absolute but no longer unchallenged. The fledgling Ferrari was beginning to show signs of effective opposition and was marshaling its forces for an assault on Alfa’s motor racing supremacy.

There was not much other opposition around. Maserati had done no development work on the 4CLT/48 since the car’s debut two years earlier and had no works team. Anthony Lago had cash-flow problems and his normally aspirated, six-cylinder Lago-Talbots were hardly competitive. Although now fully fledged Grand Prix cars with Wade superchargers, the Simca-Gordinis were unreliable, the prewar ERAs had had their day and the Alta GPs were a nonevent.

Silverstone had the honor of staging the first world championship Grand Prix, in which Ferrari did not compete. Alfa Romeo sent four 158s for their brand-new team of Giuseppe Farina, Juan Manuel Fangio, Luigi Fagioli, and guest driver Reg Parnell. And they took all four places on the front row of the grid.

Farina, Fangio, and Fagioli toyed with the rest of the field and took turns to lead the race, with Parnell watching their backs in 4th just in case. The only hiccough was when Juan Manuel made one of his rare mistakes and hit a straw bail at Stowe, after which his engine slackened and he retired on lap 62 with a broken oil pipe. So Farina won, Fagioli came in 2nd and Parnell 3rd, all of them up to six laps ahead of a mixed bag of finishers!

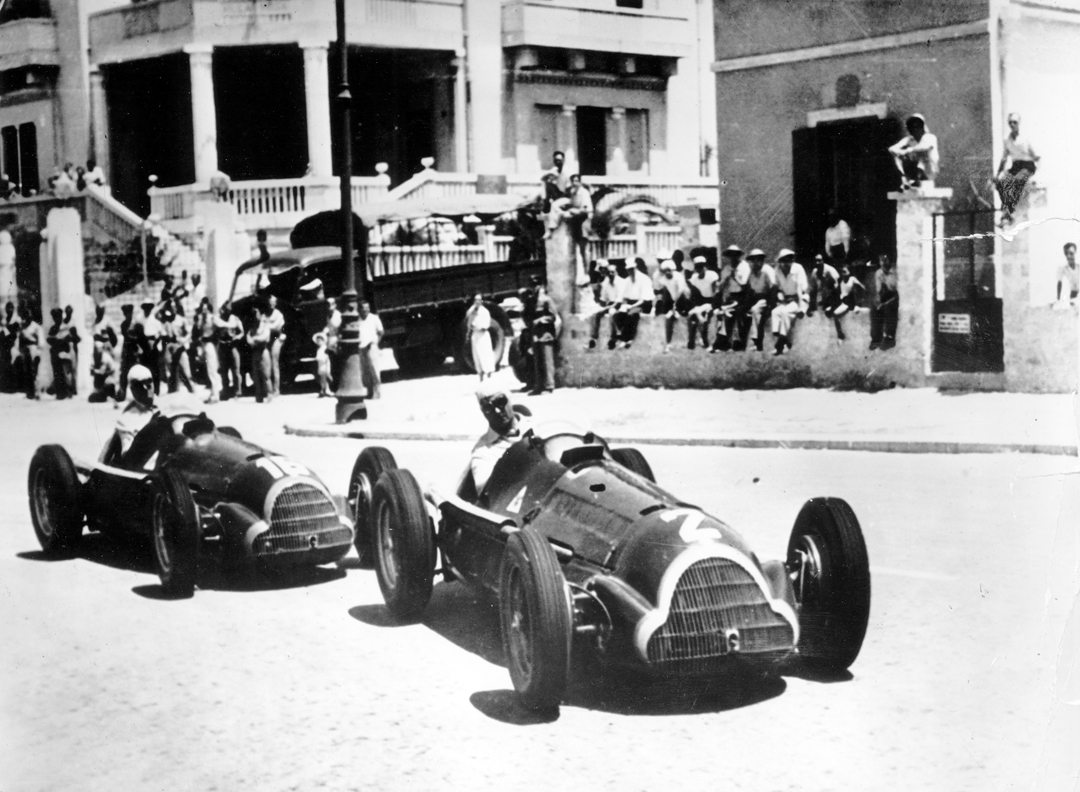

Ferrari turned up at Monaco for their first world championship Grand Prix on May 21 with 125s for Alberto Ascari, Gigi Villoresi, and Raymond Sommer. Even during qualifying it was clear the convoluted little two-mile city circuit had slashed the Alfas’ advantage, especially when Jose Froilan Gonzalez and his Maserati San Remo knocked Fagioli off the front row of the grid where he joined Fangio and Farina. The Ferraris were back in the third and fourth rows, but they were ready to give a good account of themselves.

On race day, strong winds were whipping the Mediterranean. Even the water in Monte Carlo harbor became choppy and eventually slopped over the sea wall onto the circuit’s flagstones at Tabac. Fangio had overtaken Farina to lead the race on lap one and made it through the water without incident. But when Giuseppe ploughed into the flooded section, his tires lost their grip, and his Alfa skidded and crashed. That set off a 10-car pile-up as one single-seater slammed into the other. Fangio, who was on his second lap by then, knew something was up when he saw the spectators were not watching him as leader, but the drama ahead at Tabac, so he slowed right down and gingerly picked his way through the carnage. All the Ferraris survived the debacle, but Villoresi went out on lap 63 with rear axle trouble after a dramatic climb from 9th to 2nd. Ascari took a fine 2nd place and Sommer came 4th to the winning Argentinean’s Alfetta, with wily old Louis Chiron’s Maserati 4CLT/48 sandwiched between the two of them in 3rd.

Ferrari looked like it was going to be a force to be reckoned with. In fact, it would soon become the principal challenger to Alfa Romeo and, eventually, its conqueror, but not quite yet. The next championship Grand Prix was the Swiss, where Alfa didn’t have things all their own way, even though the Ferrari challenge faded. Villoresi and Ascari both went out with mechanical problems and Alfa lost Fangio to a broken valve, before Farina and Fagioli scored an impressive 1-2 in their 158s.

Meanwhile, Enzo Ferrari had discovered the Alfettas’ Achilles heel: fuel consumption. With modified superchargers to produce even greater boost, the 158’s 1,500-cc, 8-cylinder engine was putting out a zonking 430 hp at 9300 rpm. Its problem was it guzzled well over 26 gallons of its methanol cocktail to cover little more than 60 race miles. Even though fuel tanks that virtually surrounded the driver held nearly 64 gallons, the cars still had to refuel twice during each race. Ferrari was convinced that a big, normally aspirated V-12 could be as quick as the supercharged Alfettas, if not quicker, and would use less fuel at the same time. So he instructed Aurelio Lampredi to get to the bottom of the matter.

Ferrari and Lampredi decided to take the softly, softly catchee monkey approach. A step in the right direction was the 275 S with its normally aspirated 3,322-cc V-12 that Alberto Ascari exercised for the first time on June 18 in the 1950 Grand Prix of Belgium at Spa. The car turned out to be down on power and Alberto could only muster 5th with it, so the race went to Fangio’s 158 again, with Fagioli 2nd, but alarm bells were ringing at Alfa Romeo.

After that, one Ferrari 275 S was taken to Reims for Ascari to drive in the Grand Prix of France, but it was withdrawn due to assorted mechanical malaise. Fangio won the race, with Fagioli 2nd again.

Next up was the Ferrari 375, which made its debut at the Grand Prix of Nations in Geneva on July 30, 1950. The car was up on power with a 4,100-cc engine and it gave a good account of itself, until Alberto Ascari retired it with distributor trouble. Ferrari decided the car needed yet more power, so Lampredi pushed its cubic capacity to 4,494-cc, just about the maximum permitted by FISA for normally aspirated engines, to produce an output of 330 hp and a top speed of 199 mph. And the car rocked Alfa to its foundations, not because it stood a chance of winning the 1950 world title, because it didn’t. It was too late in the game for that. But it did mark the beginning of the end of Alfa’s days at the top.

By the time the teams assembled for the Grand Prix of Italy at Monza in early September, the world championship had become a three-way, in-house fight between Fangio with 26 points, Fagioli with 24, and Farina with 22. The Argentinean qualified one of the new Gioacchino Colombo–revised 159s on pole position, but the men from Alfa were unpleasantly surprised to find that Ascari and the 375 were next to Juan Manuel on the front row of the grid, having beaten the times of Farina in the other new 159 and Fagioli in a 158.

As the cars were flagged away on a hot raceday at Monza, the three Alfettas out-accelerated Ascari’s 375 and Farina took the lead—par for the course. But Alfa was horrified to see Alberto was right on the leader’s exhaust pipes by the end of lap one. And he stayed there for 16 tantalizing laps, after which Ascari took command but lost it again on lap 22 when his rocker gear broke. He parked his Ferrari at the side of the track and began the long walk back to the pits.

It looked like Fangio’s chance of winning his first world championship had foundered when he retired his 159 with a seized gearbox. But when Taruffi came in for more fuel and tires, he was told to hand his Alfetta to the Argentinean, who was suddenly back in the fight. It was not Fangio’s day, though: His second car dropped a valve and he was out again, this time for good.

Ascari eventually got back to the pits and took over Dorino Serafini’s 375, by which time Farina’s 159 was more than a lap ahead and held the lead even after a second stop for fuel and tires. Fagioli was 2nd until his refueling stop number two, which made him lose his place to Alberto, who held it until the end of the race. So Farina won not only the 1950 Italian Grand Prix but also the very first Formula One World Championship with 30 points to Fangio’s 27, Fagioli’s 24, Louis Rosier’s (Lago-Talbot) 13, and Ascari’s 11.