Gabriel Voisin was an amazing man. Born in France in 1880, he built a four-wheeled automobile and a kite big enough to lift boys off the ground by the time he was 18. He studied architecture, but in 1900, after seeing the avion of Clément Ader, which is said to have flown under its own power in 1890, he quit architecture to pursue aviation. In an article for Automobile Quarterly, historian Griffith Borgeson characterized him as “. . . a man who could do almost anything with his hands, a mechanic, architect, engineer, aerodynamicist, inventor, captain of industry, patriot, Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor, and, due to his remarkable role in the birth of aviation, one of the human forces which helped to create the world of the Twentieth Century…. He was a full-time firebrand, a latter-day Cellini, dividing his time about equally between the creation of beauty in the form of functional design, the seduction and worship of beauty in the form of women, and his lifelong singlehanded crusade against what he called technological imbecility.”

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

Voisin was intrigued with flight and, together with his brother, opened an airplane factory—La Société des Aéroplanes G. Voisin. In January 1908, Henri Farman flew the first closed circuit kilometer in a plane of Voisin’s design. Throughout his life, Voisin believed that he, not the Wrights, had been the first to resolve all the problems of heavier than air flight. While others were building airplanes with wood frames covered in fabric, Voisin believed that an all-metal plane was a better solution, given the rough fields from which they operated. He built his first all-metal airplane in 1911 and, in 1914, the president of France announced that Voisin’s system would be used for all airplanes bought by the French Air Ministry. Voisin delivered 10,700 planes during WWI, built Hispano-Suiza and Salmson aircraft engines, and pioneered the use of machine guns, cannons and bombs on aircraft. Voisin and his company were very successful during the war, but it left him upset and feeling guilty about his role in how airplanes had been used. While he met his commitments to the Air Ministry, toward the end of the war, he turned his attention to automobiles. His company stopped building airplanes and was ready to switch to automobile production at the conclusion of the war.

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

Voisin Automobiles

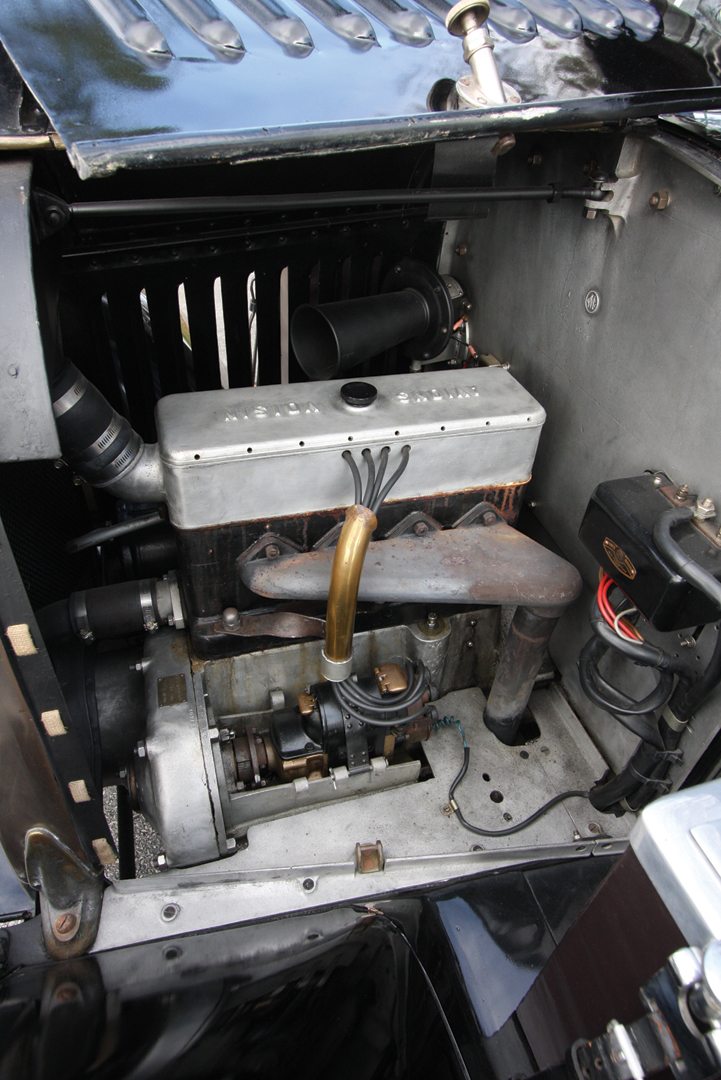

In June 1918, two young engineers named Artaud and Dufresne came to Voisin with an engine design that their employer, Panhard, did not want. It was the sleeve-valve Knight engine. With their arrival, a new automobile company was born. Voisin actually preferred steam power, but decided that it was too complicated for most owners and dropped the idea of a steam car. He liked the Knight engine because it was simple, had no valve springs, had large intake and exhaust ports, and had good potential for volumetric and thermal efficiency. With no normal valve train, it was also very quiet. The only downside was the amount of oil it consumed lubricating the sleeves, resulting in plumes of smoke behind the car. Even after progress in engine development made the sleeve-valve engine obsolete, Voisin continued to improve it, eventually setting world records for speed, distance, endurance and fuel economy with his cars.

Voisin’s “Le Grande Equipe” (“The Great Team”) continued to grow. They were joined by André Lefébvre and Maríus Bernard. The first automobile was finished on February 5, 1919. Voisin must have had a sense of humor, since when the car was started and put in gear, it shot off in reverse—something had been installed incorrectly. But Voisin just had the car driven backwards to see how it ran. One unsuspected result was that it became apparent that brakes should be put on the front as well as the back, with the greatest amount of braking effort at the front.

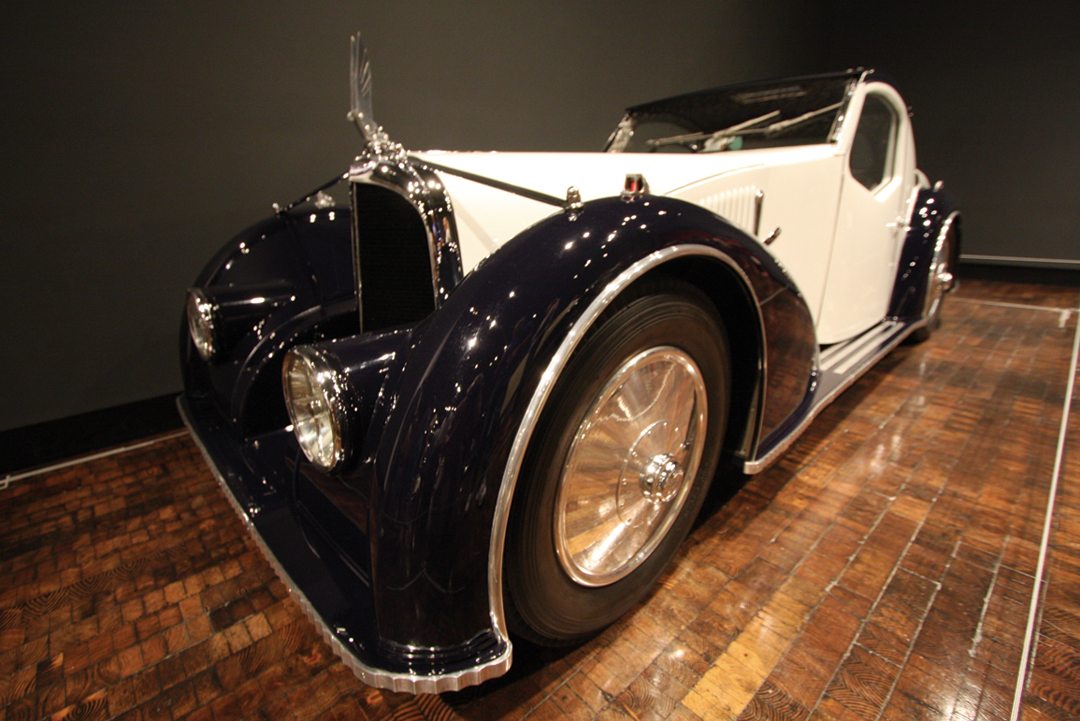

The first production Voisin was the 4-liter, 4-cylinder M1, which also became known as the 18CV. The car was capable of doing 75 mph and became a market success. Voisin’s system for establishing the model of a car was a bit convoluted. He often used the car’s physical horsepower rating, so the first car was an 18CV—CV standing for “cheval-vapeur” or “steam horse.” The physical horsepower was used for tax purposes and was not a representation of the true horsepower of the car. He also used an alphanumeric system—his 1924 car was designated a Type C4, as well as an 8 CV. There were code names for different chassis—“Chasse,” “Chassasses,” “Chastness”—as well as names for body styles—“Lumineure,” “Carène,” “Laboratoire.” The last car, the “Laboratoire,” was a very innovative racecar with an airfoil body and one of the first examples of a monocoque chassis. A radiator-mounted fan to drive a water pump for engine cooling was another innovation. While its highest point was only three feet and four inches from the ground. The Laboratoire was an example of Voisin’s understanding of the importance of aerodynamic shapes, something that would be seen in his later cars, such as the 1934 Type C27 Aérosport Coupe.

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

Many of Voisin’s designs combined his experience in aviation with his penchant for innovation. The need for airplanes to be strong and light led him to use many exotic materials and technologically advanced mechanical components. The 1920 Type C2 is a good example of Voisin’s innovative approach to his cars. The car had a 7260-cc, 30-degree V12 engine that used twin-turbine hydraulic coupling rather than a standard clutch. It employed a “Dynastart,” which was a combined starter and generator. It had four-wheel brakes operated by compressed air with 85 percent of the braking effort done by the front brakes. Because the engine produced considerable torque, Voisin used a two-speed transmission, a development that led to a two-speed transfer box. All these innovations were used on later cars.

Coachwork on Voisin automobiles exemplifies his intent for the cars to be strong and light. French roads were rough. The typically flexible chassis used on French cars made fabric bodies popular, since they reacted better to flexing than metal bodies. A strong proponent of fabric bodywork was Charles Weymann, who developed an approach that made it possible to build a fabric-covered body that was flexible enough to work on closed cars. His approach was to isolate the wood framing members from each other with an air gap and secure them with bolts or other fasteners that would not loosen because of the flexing, as screws would. The fabric was stretched over the framework, providing a strong but flexible structure. On particularly rough roads, ripples could be seen in the fabric, but the surface would smooth as soon as the road did. The colored fabric provided a soft dull sheen, which eventually was not seen as appealing as lacquer-painted metal bodywork. While fabric costs were similar to the cost of sheet metal, there were considerable savings over the cost of metalwork and painting. Voisin was familiar with fabric-covered bodies from his early aviation days, so the weight and cost savings interested him, but he wanted more strength, so he eventually replaced the wood framing with aluminum and used fabric over the aluminum framework.

The demand for high-quality small cars was increasing in the early 1920s, so Voisin had Bernard design a chassis for such a car. It was the 1243-cc 8CV Type C4. It also had innovations, including a thermo-siphon cooling system and a two main bearing engine. The C4 chassis would become the basis for some later Voisin automobiles, including the Type C4S and C7. About the time the first C7 was being produced, Voisin got a request that one of the cars on order have a mascot—a hood ornament. Voisin took some scrap aluminum and carved a series of shapes and riveted them together to form La Cocotte, “The Chick,” which became the Voisin mascot.

The peak year for Voisin production was 1925, and it was this year that he began to produce the bodies for his cars. He collaborated with Andre Noel to develop “rational” coachwork. Noel emphasized lightness, central weight distribution, and luggage capacity. This result was a kind of modular car—an assembly of boxes, one each for the engine, occupants, and luggage. The positioning of large trunks on each side and the back actually helped the weight distribution of the cars. Voisin claimed that the cars had a “good coefficient of penetration,” but the cars of the middle 1920s hardly looked aerodynamic.

Voisin continued to produce innovative automobiles into the 1930s, but the Depression took its toll on the company, as it did with many small manufacturers of expensive automobiles. In 1937, he lost control of the company, and the assets of La Société des Aéroplanes G. Voisin were acquired by Gnôme et Rhôme. Voisin remained as president, but the company was no longer interested in the kinds of innovation Voisin had promoted. Recognizing that Lefèbvre would be frustrated in the new company, Voisin encouraged him to join Citroën. Lefèbvre did, and there he designed the Traction Avant, 2CV and DS.

1927 Avion Voisin C7 Chastness

The Tampa Bay Automobile Museum (tbauto.org) houses 40 or so automobiles from the collection of Alain Cerf, founder and owner of Polypack, a company that makes machines to package consumer products. According to the museum’s mission statement, Cerf is particularly interested in “vehicles whose engineering influenced the evolution of the automobile.” Marques encompassed by the collection include Tatra, Cord, Ruxton, Tracta, and this Voisin—all examples of designs that resulted from innovative thinking.

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

The C7 was built between 1924 and 1928. During that time, 1350 of the model were built. Voisin estimated that he had built a total of 27,200 cars between 1919 and the late 1930s. Unfortunately, only about 100 Voisin automobiles survive, possibly because the use of considerable aluminum gave them a high value as scrap. This C7 is the only Voisin with its original body.

In February 2004, Cerf was looking at a website for the Citroën DS when he came across an ad for the Voisin. He was in Paris at the time, so he went to see the car. It was on blocks, so he could not drive it, but it started and ran, so he bought it and shipped it home to the U.S. When it arrived, he found that it would not drive—the differential was broken, so it had to be disassembled and repaired. On the positive side, the car came with the original trunks and the body had never been redone—it had the original fabric over the wood framing.

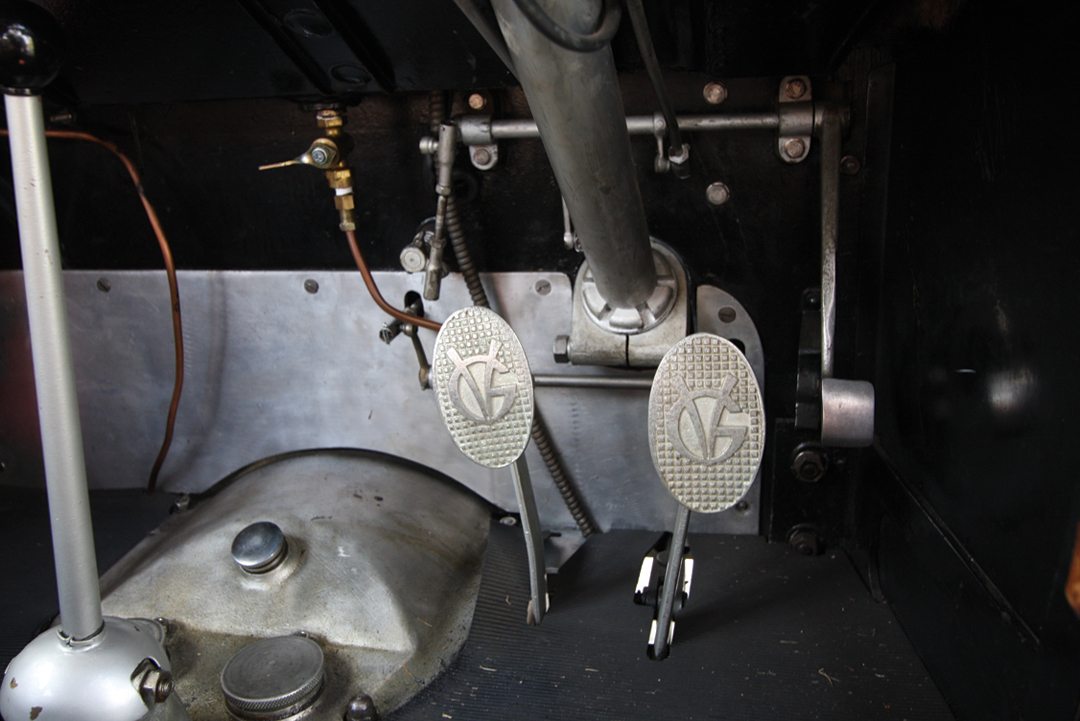

The C7 was built at a time when high-quality cars were in demand. It was built on a chassis similar to the earlier C4S, so it is dimensionally smaller than some of the Voisin cars built before and after. In appearance, it is a car of its time—it is an upright, tall sedan with a hood that seems long for its 1550-cc engine, but part of that length actually covers the space inside the car devoted to the pedals and shifters. And that is shifters, plural. The car has a three-speed transmission and a two-speed transfer case—it can be shifted through low and high ranges. As expected in a car of this quality, the interior is very comfortable and nicely finished with nice upholstery and an interesting wood dash with a tray for the miscellaneous items a driver might want to remove from his or her pockets or purse or, in this instance, a document case. One unusual feature is the operation of the side windows. There is no winder, since the rear part of the window slides forward for ventilation. To give the driver and passenger an assist in opening their window, there is an attractively carved extra piece of wood on the door frame that swings when pushed and slides the window forward. While there are door handles on the outside of the door, inside, the door is opened by pressing down on a leather strap that operates the latch. Brake and clutch pedals are textured to help keep the driver’s foot from slipping from the pedal, and part of the texturing is the initials of the manufacturer. For safety, there is both an electric horn, operated by the lever on the steering wheel, and a more primitive horn with a bulb on the inside of the car in case the electric horn fails.

Hints of Voisin’s aero past are everywhere on the car. Most noticeable is La Cocotte. This mascot is very distinctive. It is a fine example of Art Deco sculpture, but it also sends a clear message about the company’s past. Airplane hardware is evident in many parts of the car. Easily spotted are the mounting hardware for the trunks, with their knurled knobs and finely machined attachments and surfaces.

Driving Impressions

There are only a couple things to get used to in the Voisin. First, it is right-hand drive, but the pedals are in the usual configuration—gas right, clutch left and brake in the middle. And the shifter has the reverse “H” pattern we are used to in the States. It has a two-speed transfer case, which we left in high, so it was not an issue, but the shift between first and second is one of the longest I have ever experienced. You push the lever out of first and into neutral and then pull it a long way toward you before pushing it forward to catch second. The throw to third is more normal.

After settling into the comfortable and reasonably supportive seats, the starting sequence is surprisingly simple—gas on, key on, and press the starter button without pressing the accelerator. The sleeve-valve engine is very quiet—even quieter than I expected. The clutch operates smoothly, so we’re off. The first time I shift into second was a little interesting—it really is a long throw—but I got it, and we were soon into third and cruising on the smooth, divided roadways near the museum. The engine is SO quiet! But, true to its nature, we leave a trail of smoke behind us. I have learned to plan ahead when stopping an old car, but the Voisin has a brake booster to assist its cable-operated brakes.

Stopping was another pleasant surprise about the car. It did it without drama—either on the part of the car or on my part. The Voisin is not a sports car, but it handles nicely for an 87-year-old sedan. At 4150-pounds, it is not that light, but it goes well for having only 44 horsepower (10 CV if you’re the French tax man!). I found its acceleration, while not neck-snapping, certainly adequate for a car of the late 1920s. I got it up to a speed appropriate for the roads, probably around 45 mph, and found it to be comfortable on the road. I did not try to reach the 110 kmph (66 mph) top speed advertised for the car. While there were no real corners to test the car’s handling, there were a few U-turns, and the car took them smoothly and without much body lean. It was a nice drive in a very civilized car.

SPECIFICATIONS

Body: Fabric over wood framework

Chassis: Steel frame

Wheelbase: 112.9-inches

Length: 159.5-inches

Width: 58.1-inches

Weight: 4150-pounds

Suspension: Leaf springs front and rear

Engine: Sleeve-valve inline four cylinder

Displacement: 1550-cc

Bore/Stroke: 67/110-mm

Power: 44 hp (10 CV)

Induction: Zenith side draft carburetor

Ignition: Magneto

Transmission: Three forward gears with a two-speed transfer case driving the rear wheels

Brakes: Cable operated, 280 mm drums, with brake booster

Wheels: 18-inch wire wheels

Tires: Bergougnan 5.50-18