I couldn’t quite pinpoint why, during the research and writing of this profile, that I kept hearing the Lennon/McCartney hit “Come Together” somewhere in the back of my head. I have often used the metaphor of how some of the most interesting motor racing tales are based on an almost accidental “coming together” of a number of threads, people and incidents. But this seemed different.

The 1969 Beatles hit was inspired by the drug-taking Timothy Leary and his campaign against Ronald Reagan to become California governor…Leary went to jail for possession. The song was unlike any other of the period, constructed only of verse and refrains, there were legal battles in America over it, it was considered a radical structure, it was a big hit in the USA, and everyone wanted to copy it….ah, now it’s “coming together.” I hear Max Mosley and Robin Herd “marching” in downstage left, and the Daytona drum and bugle corps strutting their stuff on a warm February morning in 1984. I hear lawyers arguing about which car is which! It’s eerie…even a bit “kreepy.”

Photo: Mike Jiggle

The March to Daytona

OK, where do we start with this somewhat convoluted story of sports car racing in the IMSA/Group C days, when ferocious new cars appeared and tackled the mighty Daytona 24 Hours, when teams and manufacturers fought tooth and nail over design, when money from sometimes dubious sources was finding its way into racing, when racing drivers found themselves in jail…and when a South African swimming pool company found glory in Florida?

Let’s start the tale in the less than tropical climes of Bicester in England. The first March racing car had appeared in competition on September 28, 1969, an F3 car in the hands of Ronnie Peterson at Cadwell Park. The story of March, which Mike Lawrence called “four guys and a telephone” had a dramatic start and March catapulted into Grand Prix racing only months after the Cadwell debut. The four guys, Max Mosley (M), Alan Rees (AR), Graham Coaker (C) and Robin Herd (H), formed a dynamic team which had a lasting effect on motor racing. In 1970, they built cars for F1, F2, F3, Formula B(Atlantic), FFord 1600 as well as three Can-Am sports cars. By the end of 1973 they had built a total of 299 cars, including the three Can-Am machines and 19 2-liter Group 5 sports cars. By 1980, that figure had reached 872, but by far the large majority of these were single-seaters.

Then in 1981, the company unveiled the 81P for BMW and this car became the basis of the cars March would construct for the IMSA and Group C series for the next seven years, through 1988. David Hobbs drove the first 81P, or BMW 1C as it became known, to some good results using either the 3.5-liter or 2-liter turbo engine, though the car was somewhat fragile. For 1982, March built four cars for Group C and the IMSA GTP categories, with a honeycomb monocoque, and wishbone-coil spring front and rear suspension, this was the 82G. An 82G with a Chevy engine appeared at Silverstone and Le Mans in Group C, and cars with both Chevy and BMW power ran in a number of races to IMSA rules. March was well involved in F1 and F2 and had built 20 cars for Indy races, so the sports cars perhaps got a smaller slice of the “design pie.”

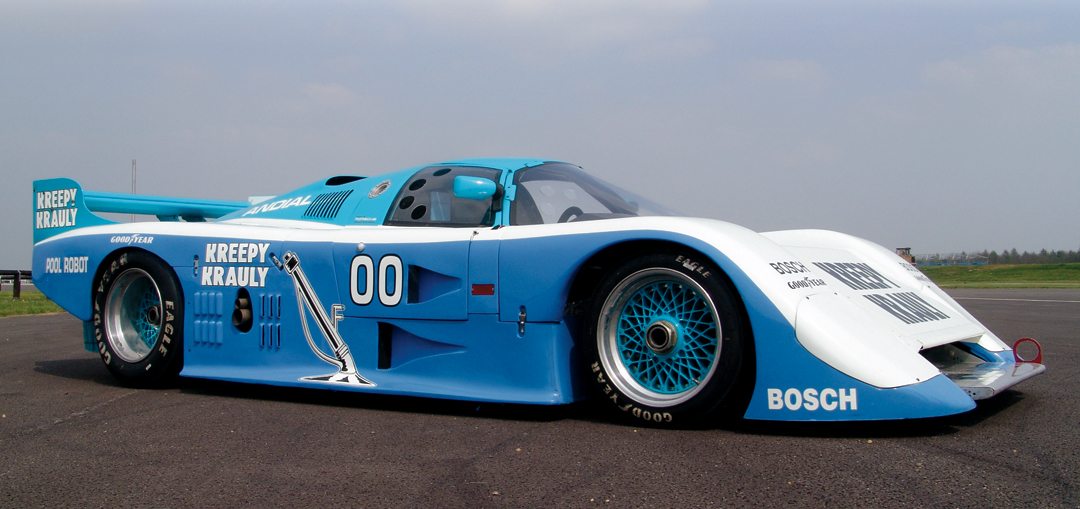

In 1983, March produced five new cars, 83Gs, for Group C and IMSA/GTP. March had a great Indycar season, with Tom Sneva winning the 500 and Teo Fabi winning at Phoenix, and the success started to spread to the IMSA cars, especially to Al Holbert. In 1982 the 82G cars—82G/1 through /4 had gone to Garretson Development, Red Lobster Racing, Momo Racing and to…March. March UK and March USA both ran 82G/4. For 1983, the new machines were sold as follows: 83G/1 to Ken Murray, 83G/2 to Holbert Racing, 83G/3 was an update of 82G/3 for Momo Racing, 83G/4 also to Holbert Racing, and 83G/5 to Hoshino Racing in Japan. 83G/4 is one of the two cars you see on these pages.

The 83G was an evolution of the 82G, which had been the first car to be designed by a young man now known for his rather impressive success with a variety of F1 teams. Now with Red Bull, Adrian Newey is undoubtedly one of the most talented people ever seen in the racecar design world. The 83G was conceived very much as a customer car with an engine compartment that would be suitable for a range of engines from the Chevy V8 to the flat-6 turbo Porsche unit. The bodywork had been drawn by Max Sardou of Porsche 917 fame. The “lobster-claw” front end would become a March trademark, and it was fateful that Red Lobster Racing should be one of the teams to use an 82G.

Chassis 83G4 first appeared in mid-May 1983 at the Charlotte Camel GT race, where Al Holbert and Jim Trueman gave the car its first victory, and Holbert was 9th though not running at the end of the Labatt’s Can-Am race in early June. This car, of course, had the Porsche F6 2600 turbo engine, though Holbert also drove cars powered by the Chevy unit early in the year. Holbert and Trueman had another win at Sears Point in July, Holbert repeating that a week later in the Portland 3 Hours. He and Trueman were then 7th at the Mosport 6 Hours, 15th at Road America, endured a DNF at Pocono and then in November were back in the winner’s circle with a fine drive at the Daytona Finale 3 Hours. The Holbert team was very happy with their season, but even more was to come.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

The background to American racing in the period was as colorful as the racing itself. There was big money floating about, and as it turned out, some of it came from “interesting” sources. Randy Lanier was one of the successful drivers during this era, taking the GTP title in 1984 and going on to Indycars. He shared drives with the well-known Whittington brothers, and ran his own team with partner Ben Kramer. What they didn’t know was that the FBI was investigating them for suspected importation of marijuana. Kramer was a nephew of an alleged leading American crime boss. In 1987, Lanier and Kramer were indicted and received life sentences without parole under a new law pushed hard by President George H. W. Bush to show how tough on drugs he was. The Whittingtons got lighter sentences. Father and son team John Paul Sr. and Jr. were also big names in the period, Jr. winning the Camel GT title in 1982. Both were convicted of drug trafficking and served sentences, Paul Sr. finally dropping out of sight after being questioned about the disappearance of his female partner from the boat they shared. Good ole, bad ole days!

Kreepy Krauly comes on board

In spite of the occasional lurid headlines, motor racing was mainly populated by honest, hard-working folk. Holbert’s subtle changes and development of his two team cars had won him the 1983 IMSA championship, and made the cars even more desirable. The Chevy-powered 83G/3 was sold on to David Cowart while Holbert sold 83G/4 to what was essentially a brand new and unknown team from South Africa with a very memorable name—Kreepy Krauly Racing.

Sarel van der Merwe had had a modest career in racing in South Africa, but managed to get a drive with Momo Corse in the IMSA series in 1983 in a Porsche 935. He had taken part in the Daytona 3 Hours in November, and was a key part of the effort to put together a serious season for 1984. With fellow South Africans Tony Martin and Graham Duxbury, they got sponsorship from a company making its name developing swimming pool and spa equipment, Kreepy Krauly. The company had developed a successful range of equipment, especially a very effective suction pool cleaner, and the motor racing involvement was aimed at establishing themselves in a global market. Today, they remain in that market.

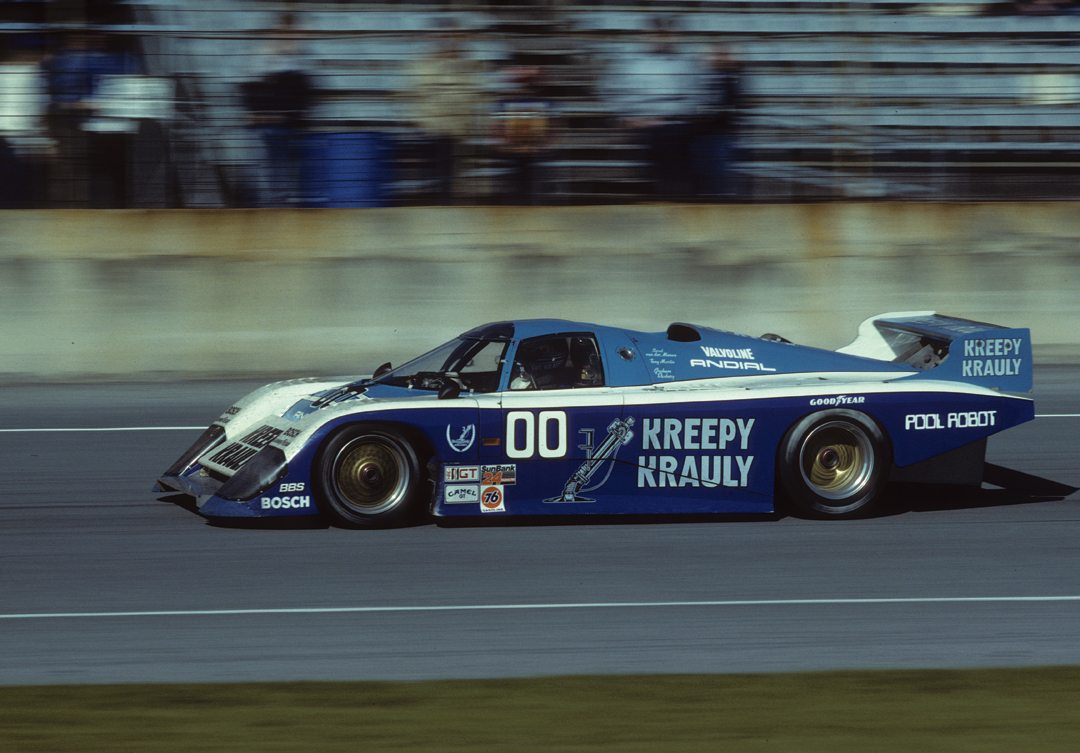

Van der Merwe was the only member of the new team to have been to Daytona before, but the circuit had been changed somewhat, with a new chicane, and had been lengthened slightly. The entry was very competitive, with 18 IMSA GTP cars as compared to only two the previous year. All the big money was on the Porsches, though IMSA had long been wanting to see the GTP cars get a big win. Mario and Michael Andretti had put the works Porsche 962, chassis 001, on pole for the race, but there next to him sat the brightly painted Kreepy Krauly March, ahead of the Bob Tullius-entered Jaguar XJR-5 and A.J.Foyt, Derek Bell and Bob Wollek in a Preston Henn 935L. Fifth were Randy Lanier and Bill Whittington in a March 83G-Chevy with the second XJR-5 6th.

Mario and van der Merwe sprinted away at the start and were soon lapping the slower cars, something the Porsche was better at than the March. The XJR-5 was in front at the pit stops but Michael Andretti soon got back into the lead. Then the Andretti Porsche had the gearbox fail, and several cars took turns in the lead. Ken Howes was managing the Kreepy Krauly outfit, but had said openly that the team had very modest expectations and would probably not be around for long. So the decision was made to put on a good show for as long as the car ran, expecting to be out in the early evening hours. The March ran near the front, but had gear lever problems and dropped to 8th. The Jaguar led in the 6th hour, but when its alternator belt broke, the March went back into the lead…until Tony Martin ran out of fuel and had to run back to the pits. An electrical failure had closed the auxiliary fuel switch.

Foyt then led in the 935L until suffering body damage, and with other cars having problems, the Kreepy Krauly car was again in the lead at 1:30 a.m. From that point on, the three South Africans drove smoothly to a nine-lap victory over the Henn 935L, with the Jaguar 3rd and Holbert, Haywood and Ballot-Lena 4th in another 935. It had been a stunning victory for 83G/4 and for the Kreepy Krauly team in this famed international event. It did indeed put the team and the company on the map.

“We were in shock,” said Ken Howes. “We were also worn out—we hadn’t slept in a week. I guess you can say we had beginner’s luck. We ran out of gas once, and the gearshift knob came off, but other than that we had no real problems.”

Not long after Daytona, 83G/4, still bearing the double zero race number, ran in the Budweiser Miami Grand Prix where van der Merwe and Martin were 8th. The Daytona trio were together again at Sebring where the Marches and Lola T600s would fight hard with each other. The South African team was 2nd on the grid behind the Redman/Bedard Jaguar XJR-5, while Lanier and Bill Whittington in the Blue Thunder March 83G-Chevy were way down in 64th. In the race, 00’s engine went, and Blue Thunder charged up to 2nd behind the winning private Porsche 935.

Sixth was the reward at Riverside at the end of April, and then van der Merwe had an impressive 3rd at Laguna Seca, a DNF at Charlotte and a very impressive victory at Lime Rock on May 28. The South African trio were 5th at the Mid-Ohio 500 Kilometers and the car was then sold to John Hotchkis to be run by Hotchkis Racing. Hotchkis ran it once in 1985 at Riverside, then had a DNF at Daytona in 1986, 14th at Miami, DNF at Sebring and 6th at Riverside before going into “retirement.” This car, with the single turbo Porsche engine, resides in Pennsylvania and will be appearing at the Rolex Daytona Reunion by the time you are reading this!

The “other” Kreepy Krauly…84G/3

When we first encountered 84G/3, it was carrying a chassis plate identifying it as 84G/1, so when it came time to put this story together, the identity issue triggered what has been an intriguing and sometimes frustrating search. Having spent ages in trying to work out how a Porsche engine got into a car which had always been powered by a Chevy, it turns out that a simple error had been made during the restoration and the wrong chassis plate went on!

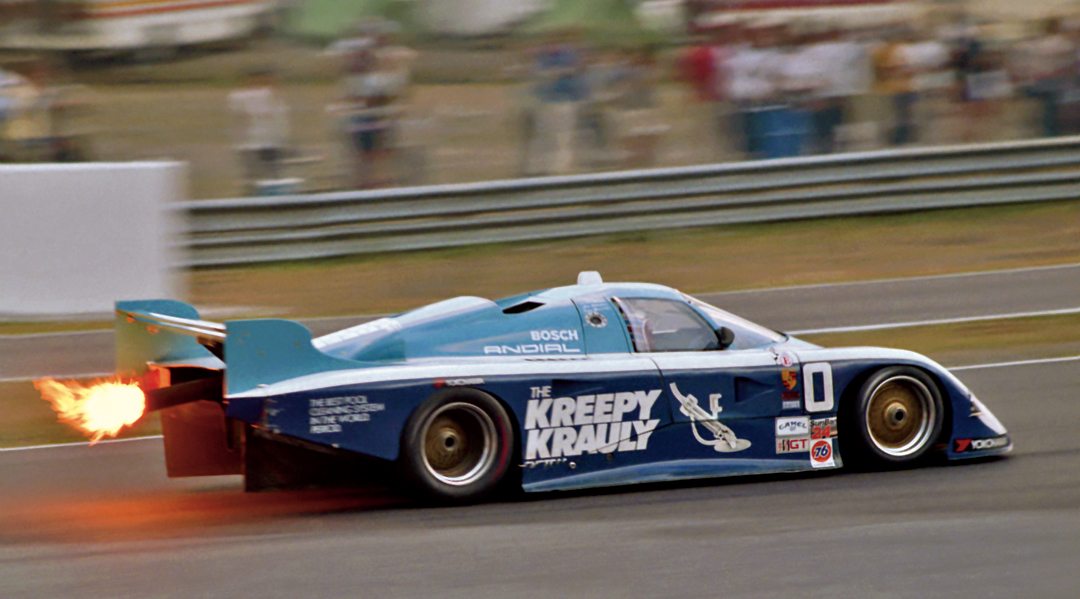

Turns out that 83G/4 was a 1983 car updated to 1984 specs while retaining its original identification. When that car was sold to Hotchkis, the Kreepy Krauly team purchased a new car…84G/3. It was entered for the Watkins Glen 6 Hours but was not ready on time so made its debut in van der Merwe’s hands at the Portland 3 Hours where it promisingly qualified on pole, but then failed to finish. The team skipped the Sears Point race to concentrate on the Road America 500, where another South African, Ian Scheckter, Jody’s brother, joined van der Merwe. They qualified and finished 4th, a good result. In September it was Tony Martin joining van der Merwe at Pocono where they were 3rd on the grid and again finished 4th. The car was still running the original turbo Porsche engine from specialist tuners Andial, which turned out to be quite reliable. The same driving duo were 5th quickest at the Michigan 500 but did not get to the flag, and then Scheckter returned for the Daytona Finale 3 Hours where the car was again 2nd on the grid but a wheel hub failed and they were classified 6th at the end.

There was a big build-up to the 1985 Daytona 24 Hours where the team was very much hoping for a repeat of their staggering victory the previous year. Van der Merwe, Scheckter and Martin were the drivers. The expected March vs. Lola battle did not materialize in qualifying, and the John Paul Jr./Bill Adam/Whitney Ganz March 85G-Buick snatched pole from “our car” with a trio of serious looking Porsche 962s next, followed by the Lanier/Bill Whittington/Al Leon March 85G-Porsche 6th. John Paul Jr. went out in front at the start chased by van der Merwe, but the Kreepy Krauly car began to have fuel pickup problems. The Porsches led after the first stops and by Sunday morning they had the first five places. That was how it finished. The South Africans could not repeat the 1984 win and retired on lap 260 with tire problems.

After that, 84G/3 went to Le Mans in Group C trim where it was entered by Kreepy Krauly and driven by Christian Danner, Graham Duxbury and Almo Coppelli. It was 24th on the grid and finished 22nd. Van der Merwe, who owned the car, swapped to a Kremer Porsche in which he finished 5th. It was a fairly undramatic event for the Kreepy Krauly team. The car had been rebuilt to Group C specs, so now had the twin turbo 2649-cc Porsche engine.

After Le Mans, the car was sold to Costas Los and was run by Cosmik Racing with sponsorship from the Greek brandy company Metaxa. It appeared at Hockenheim, Mosport, Spa, Brands Hatch, Fuji and Selangor. It was driven by Los, Danner and Mikael Nabrink, getting 7th at Spa and Brands and 8th in Malaysia. In 1986, the car ran at Monza with Los and Danner driving, finishing 13th. Los was joined by Canadian John Graham at Silverstone, but they retired with engine problems. It then appeared for a second time at Le Mans with Los, Neil Crang and Raymond Tourout where it qualified 45th but was disqualified for receiving outside assistance. There was a DNF at the Norisring, 9th at Brands Hatch and Jerez with Los and Tiff Needell, 10th at Nürburgring with Los and Volker Weidler, and 18th at Spa with Needell/Los. It then ran at the Supersprint race at The ’Ring and ended its period career with Los and Needell taking 18th at Fuji on October 5, 1986.

Chassis 84G/3 was purchased in recent years by Andrew Haddon, and in 2008 was restored to its 1985 Le Mans livery, so it was back in the bright colors of Kreepy Krauly racing, in which it now makes occasional appearances in historic Group C events. Kreepy Krauly continued in racing for some years in other categories, and the company has now established itself as a leader in its own field, which was the original intention.

Photo: Karsten Denecke

Driving 84G/3

March had gone on to produce 11 Group C and GTP cars in 1985, the GTP versions using mainly BMW engines, while Nissan now joined Porsche in a serious assault on Group C. Nissan put a huge effort into developing Group C cars, but that is, I think, another story. There were 11 more Group C/GTP cars in 1986, three in 1987, only one in 1988 alongside eight Grand Champion Can-Am style cars for Japan, and two more of these in 1989, but no other sports cars. March had entered the Leyton House/Akagi period which was to bring it to the brink of liquidation, meaning the old glory days of the marque were over. Akagi had bought the March racing operation which carried on until Akagi was arrested in the 1991 Fuji bank scandal. Fortunately, some of the beautiful cars of that period survive, including the Adrian Newey-designed Leyton House March F1 car.

The Group C and IMSA cars also survived the ravages of racing and time. I made my acquaintance with 84G/3 on a Silverstone test day where a number of Group C machines were getting an airing. I have had a few sessions in this kind of car and I don’t think I ever quite get used to the experience.

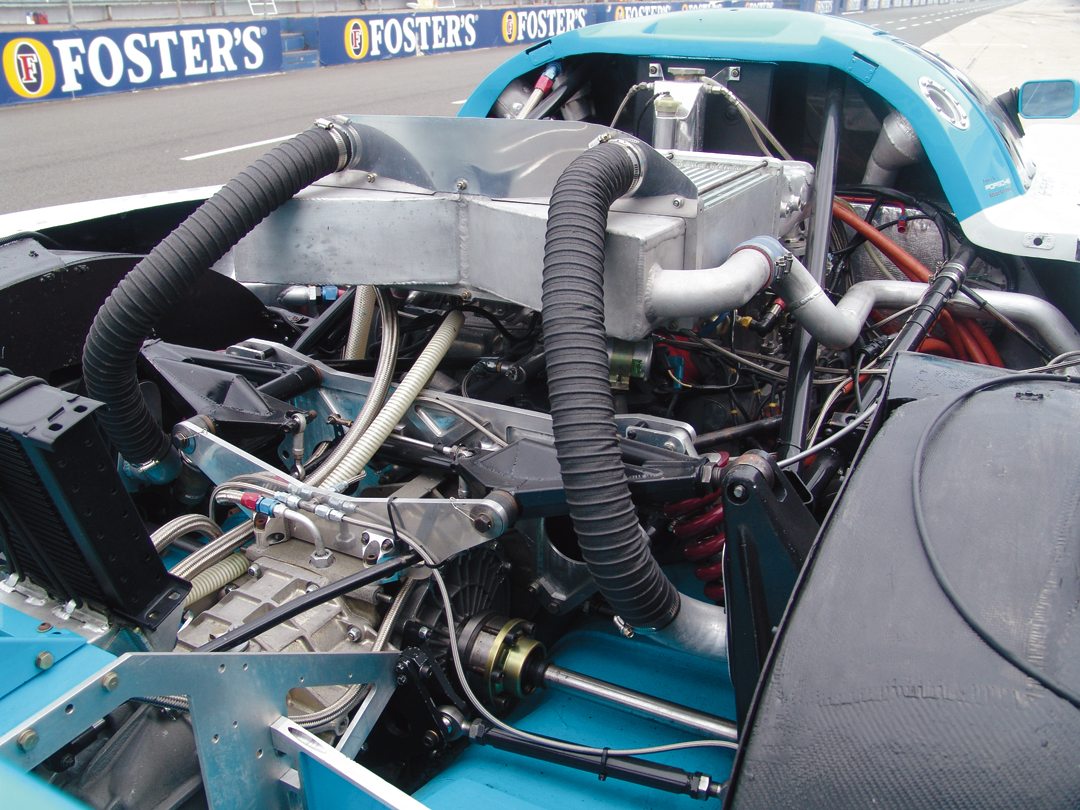

For the devotee of historic cars, Group C racers are pretty futuristic. I have found that, for a practice session, it’s best not to look round at the technology too much…it can be overwhelming. 84G/3 had a well used and modified race seat that had been occupied by a variety of other drivers of differing sizes, but a cushion soon sorted me out. You are faced with the Momo 3-spoke wheel behind which sits the rev counter…this one reads to 10,000 rpm but was red-lined at 7500. To the left are water temperature gauges, the boost gauge, oil temp and pressure gauge, fuel warning lights and to the far left a large array of light and pump switches, with the extinguisher on the floor. To the right, you find oil warning lights, the ignition switch and starter button, and far right the gear lever connecting you to the very lovely 5-speed gearbox. For our test, I was assured I could just keep my eyes on the rev counter and the road!

Photo: Paul Kooyman

At low speed the Porsche flat-6 is not impressive…that comes later. The sales brochure always said these cars were user or customer friendly, and indeed they are. While my first attempt at a Group C Lancia got me into real trouble, this car was much more manageable and provided the chance to get the tires properly warmed up. With the Lancia I kept falling off the road before the rubber was barely warm!

The general advice you are given with a Group C car, especially one with effective downforce potential, is “brake late, don’t lift, stay on the throttle, keep the revs up.” That is always daunting when you are in a car you don’t know. This March, however, was more forgiving. Getting up to speed, the fact that the all-round visibility and rear vision is good was very reassuring. Nothing worse than being in a fast car with faster cars around that you can’t see. The March rates highly in this department, providing the chance to get to grips with the fabled Porsche engine that is turning out some 600 bhp. Though our test didn’t allow for any serious high-speed runs, the manageable torque and flexibility of the engine was abundantly obvious.

A Group C car has to work hard. Though Silverstone doesn’t have a lot of tight corners, the few there demand perfection from the all-round ventilated discs. You carry vast speed into a corner, come hard on the brakes…keeping the throttle on. Group C cars work if they are flattened to the ground in corners, and that puts immense stress on the machine. That this March 84G could put up with abuse from a non-expert was again tribute to just how user friendly it is. As I always say at the end of a Group C test…a bit more please…and can I get my swimming pool cleaned?!?

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Honeycomb aluminum monocoque with semi-stressed engine

Body: Kevlar

Wheelbase: 105.7 inches

Suspension: Double wishbones, coil springs over dampers, anti-roll bars front and rear

Steering: Rack and pinion

Weight: 900 kilograms

Engine: Porsche flat-6 twin turbo

Horsepower: 600 bhp, 0.69 bhp/kg

Transmission: 5-speed manual March-Hewland

Brakes: Ventilated discs all round

Tires: Goodyear Eagle – front 23.5 x 10-5-16, rear / 27.0 x 13.0-16

Acknowledgements/Resources

Many thanks to Andrew Haddon for the use of his car and to Phil Stott for his usual unstinting support. www.philstott.co.uk

Lawrence, M. The Story of March

Aston Publications Bucks, UK 1989

O’Malley, J.J. Daytona 24 Hours

David Bull Publishing Phoenix, AZ 2003