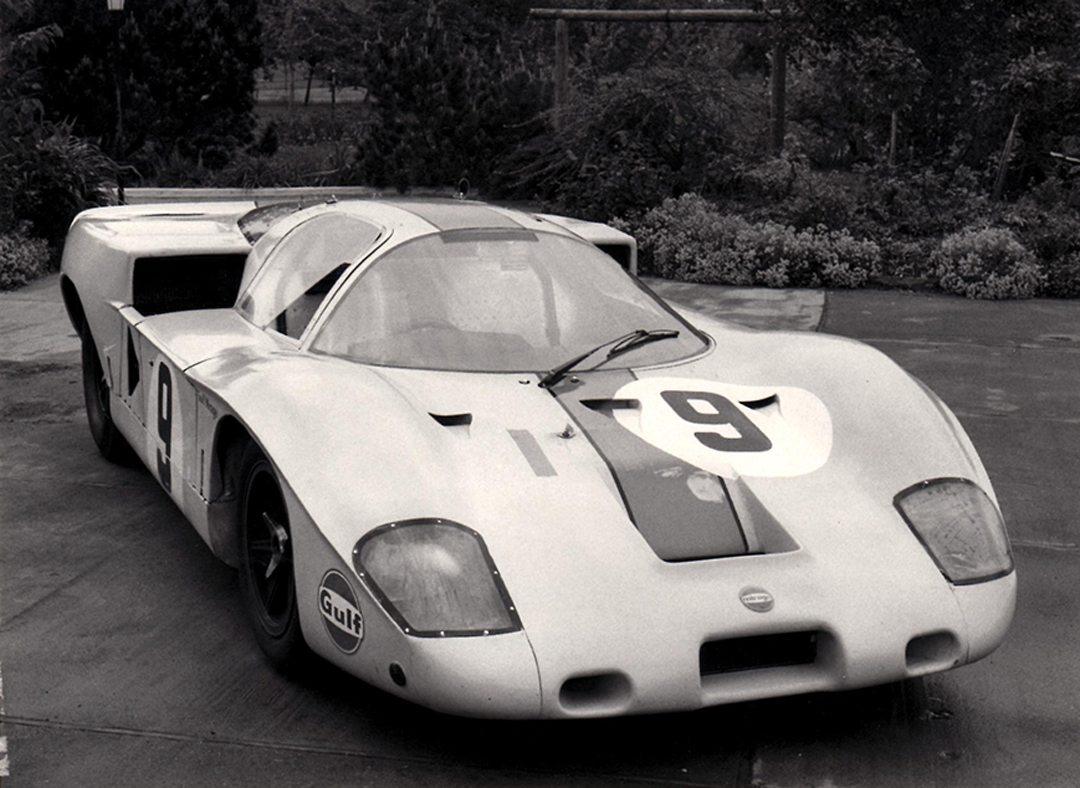

1969 Mirage M2-BRM

The Mirage profiled here is no optical illusion, although it is certainly as beautiful as some optical illusions can be. Only three Mirage M2s were ever built. They showed potential in the World Sports Car series, but their development was cut short when Porsche came knocking at John Wyer’s door. One of the three cars, M2/300/03, has been restored to its condition when it scored the best finish of any of the three cars. The story of M2/300/03 can only be told by also telling the story of four men who have been intimately involved with the car—John Wyer, John Horsman, Gary Kachadurian and Bob Russo.

John Wyer & JW Automotive Engineering Ltd

Opinions differ about what it was like to work with John Wyer. It was said that he wore dark glasses to protect his mechanics from his “Deathray,” a name that some used when talking about him. Other saw him as a brilliant engineer and team manager, someone who would think very hard before making what often proved to be the correct decision. Most agree that he was very demanding, had little tolerance for failure, had quite a temper and was sometimes rude. He was also very successful.

Wyer served an apprenticeship with the Sunbeam Motor Company before joining Solex Carburetors in 1933, staying with them through WWII. After the war, he left Solex to run Monaco Motors and Engineering Company for his friend, Dudley Folland. Monaco Motors was a small company that had an excellent reputation for preparing racing cars. One success came from his directing the work on three 1.5-liter HRG chassis and preparing them for Le Mans in 1949. The chassis were stripped, lightened and rebodied by Monaco Motors. One of the cars won its class at Le Mans, and the HRG team went on to dominate the 24-hour race at Spa.

Then came the Ford-Ferrari wars. At a meeting in Maranello, in May 1963, Ford thought it was about to buy Ferrari, but a clause in the proposed contract incensed Enzo Ferrari—he would not give up his racing program to Ford, but that was what Henry Ford II had come to Italy to buy. Ford wanted to be in racing at the successful end of the sport, and what he thought was a done deal was undone. Ford and his execs went home angry, which led to the next stage in Wyer’s career.

After initially trying to develop the Lola MK6, Ford decided to open its own facility in Slough, England. Wyer was hired to manage Ford Advanced Vehicles (FAV) and develop the GT40 into a car that could win Le Mans. Unfortunately, reliability issues plagued the cars through 1964, resulting in Ford handing development of the cars to Shelby and Holman and Moody. FAV was then tasked with building and supporting customer road and race GT40s.

Well before FAV, Horsman got to know Wyer as a result of taking photographs of cars at races. He was an engineering student and sent some photos to Aston Martin, which they used in advertising. Subsequently, he wrote and asked for a job. A meeting was arranged with Wyer, and Horsman was given a job offer once he obtained his degree. Horsman was primarily involved with roadcar development at Aston Martin, until Wyer’s departure. Aston Martin had returned to racing, and circumstances left Horsman the “last man standing” to manage the team at Monza in 1963. He made good decisions at the race and impressed some people. Apparently those people included Wyer, because Horsman joined FAV shortly after the dismal Le Mans effort in 1964 with the GT40s. In an interview with Motor Sport magazine in December 2014, Horsman lamented the situation at FAV, “There was lots to do, because the car was unstable, the guys who’d designed it had no racing experience, so it was too heavy, and the engine was no good.” And the decision-making process was unhandy, “John would go to the States and have a meeting with the powers that be, but there were too many fingers in the pot and not much got done. They’d eventually take decisions, but by the time John returned to base it had all changed, so his trip served no purpose. It was a case of order, counter-order and disorder!” With Ford putting the emphasis on development with U.S. companies, and Wyer’s preference for streamlined control, it was time for FAV to be dissolved and JW Automotive Engineering to be formed.

Mirage

Wyer had a contract to build and maintain customer GT40s. Initially, it was for 100 cars but was subsequently reduced to 50. Still, Wyer knew a lot of people because of their cars. In April 1966, Grady Davis, a Gulf Oil executive, took delivery of his GT40 and was very pleased with the car. His pleasure caused him to help Wyer more than might initially have been imagined. Davis worked to establish Gulf Oil Racing to support Wyer’s racing efforts. That financial support became particularly important in 1967 when the FIA changed the rules to promote prototypes rather than GT cars. The new rules had many restrictions, but there were none on engine size or number of cars produced for the prototypes. Len Bailey drew a new car, not unlike the GT40, but that took advantage of the rules. The car would have a 4999-cc engine, ZF gearbox and Girling disc brakes. It had a lower frontal area for less drag and a lighter fiberglass body reinforced with strands of carbon fiber. Wyer had a new car, but the car had no name. He and Horsman created lists of potential names. The only name that appeared on both lists was “Mirage,” so Mirage it was. The livery for the Mirage M1 would be the Gulf colors—light blue and marigold—which have become so iconic. One interesting bit of trivia is that the blue is that used by Gulf in California, not the international company.

The 1968 season was a very good year for JW Automotive Engineering. Wyer ran two cars in most of the races in 1968, except at Le Mans, where they entered three. There were no Wyer cars at the Targa Florio or Zeltweg. Results included wins at Brands Hatch, Monza, Spa, Watkins Glen and Le Mans. Jacky Ickx was the driver credited with the most wins for the GT40s, although while partnered with drivers including David Hobbs, Brian Redman and Lucien Bianchi. Le Mans, the last race of the championship in 1968, was won by Bianchi and Pedro Rodriguez.

Wyer’s blue and marigold cars took five wins, and one each of 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 6th place finishes. There was a young Army First Lieutenant at the May race at the Nürburgring, where Ickx and Paul Hawkins finished 3rd in the #65 car, and Hobbs and Redman took 6th in the #66. A couple of that soldier’s photos of the Wyer/Gulf GT40s are included with this article.

Mirage M2

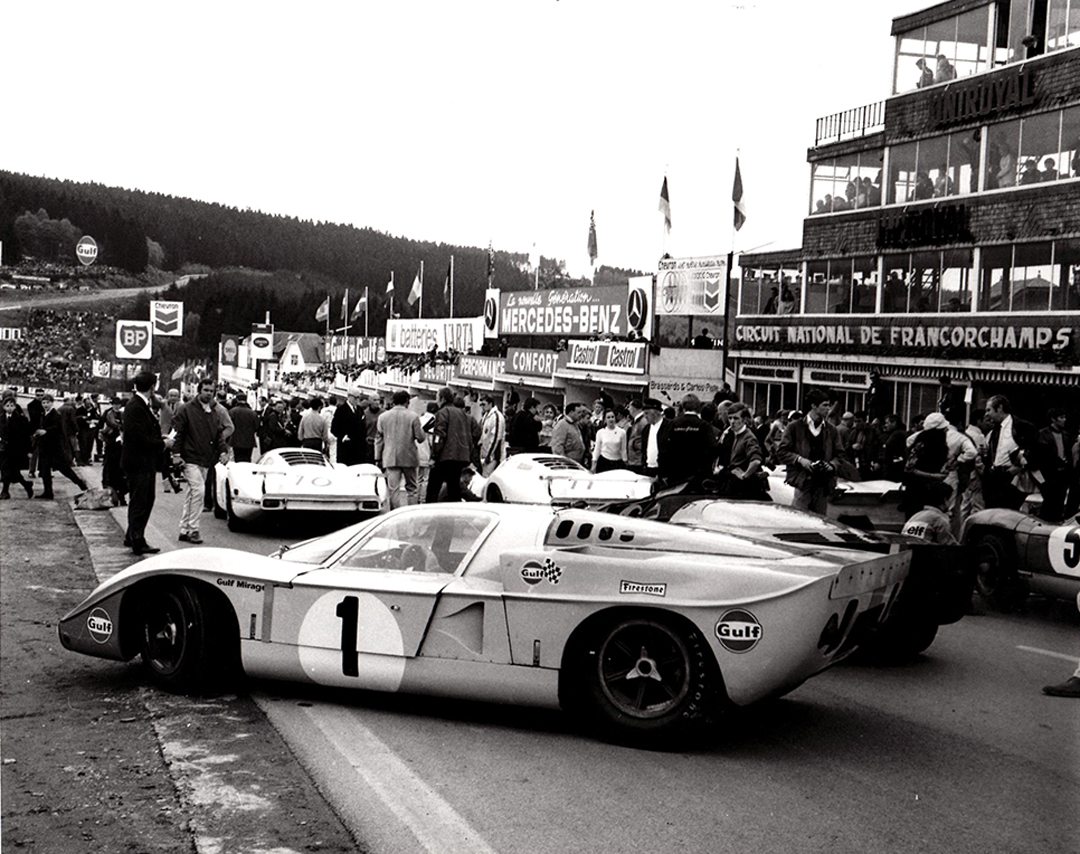

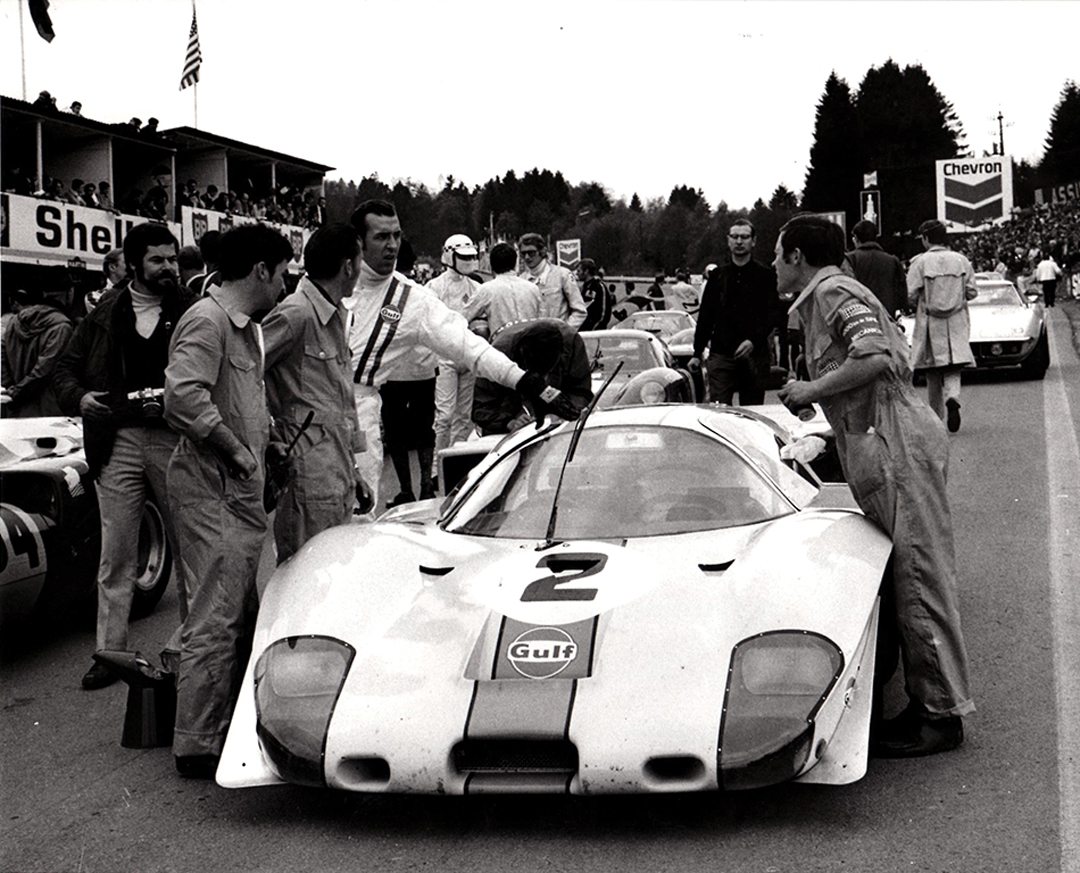

In April 1969at Brands Hatch, Ickx and Jackie Oliver had qualified M2/300/002 11th and were running 7th when the car broke. The good news was that it was faster than the Hobbs/Mike Hailwood GT40. After taking a pass on Monza and the Targa Florio, the team went to Spa in May 1969. Ickx and Oliver qualified M2/300.002 2nd on the grid, but fuel pressure problems took it out of the race. It was M2/300/003 with Hobbs and Hailwood driving that took the best result for a Mirage M2, 7th overall. The last race for the M2 was the Nürburgring in June. The Ickx/Oliver car now had a Cosworth DFV, and the Hobbs/Hailwood car received a new 48-valve BRM V12. Sadly, neither would finish. Ickx had suspension problems, and a miscalculation on the fuel consumption of the BRM left the car on the side of the track, out of fuel. The M2s were subsequently sold to Jo Siffert, who had a business dealing in used racecars. For the rest of the year, Wyer raced Mirage M3s, which were very pretty, but unreliable, open cars—although Ickx had a magnificent win at Imola, leading before and during a terrific rainstorm. For the next few years, the cars raced under the Wyer banner would be Porsches.

M2/300/003

Enter Gary Kachadurian and Bob Russo into the history of the Mirage M2 and to its rescue. Of the three Mirage M2s, M2/300/003 is the only one that has been returned to its original condition when it was raced. M2/300/001 was turned into an open car, and is in a private collection in England. M2/300/002 was held by Siffert for a number of years, then sold to George Hurd, a vintage racer with a relationship with the Bethlehem Steel company, which is where Kachadurian found it.

Gary Kachadurian is particularly enamored with racecars, and with history. He owned the 2000 Porsche GT3 RS once driven by Paul Newman. In 2012, he bought the BFG Porsche 962 Jim Busby team car driven by Jochen Mass and John Morton. After a restoration by Bob Russo, Kachadurian entered it at the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance in 2014 where it won the award for the Most Significant Race Car of Jochen Mass, who was that year’s honoree at the concours. Kachadurian recently bought the Flying Lizard Porsche GT3 RSR that finished 3rd at Le Mans in 2005 and 4th in 2006.

When Kachadurian heard that a Mirage M2 might be for sale, he acted quickly and bought the car in 2016. It was an easy decision to restore the car to its original condition when it ran at the Nürburgring. To do the restoration, Kachadurian sent the car to Bob Russo, the man who had restored some of his other cars.

Russo’s path to being a restorer of historic racecars was circuitous. He was always interested in cars, but he tried a variety of other careers—teaching school, doing engineering design for a pump company, working for a construction company—but it was a move to a job near Bob Holbert, in Pennsylvania, which finally led him to a career in restoration. He had been working for a construction company and building engines for Porsche owners on the side, when Al Holbert called and offered Russo a job selling safety equipment for Holbert Racing Sales. Russo also worked in the race shop on cars like the Chevy Monzas, a NASCAR Monte Carlo, Can-Am cars and Porsche 924s, which they developed as racecars. In 1985, Russo was involved with Holbert’s Lowenbrau-sponsored 962, a car that won 23 of its 50 races, including Daytona in 1986 and 1987.

After Holbert’s tragic death in a 1988 plane crash, Russo helped the family close Holbert Racing Sales, but he also worked for Kevin Doran Racing, and formed Race Ready Technologies, a restoration/racing facility. He continued to take the Lowenbrau car to shows and developed performance parts for Porsche racecars. He also began doing restorations, including the RC Cola Porsche 962, Greenwood Corvette and GTP Corvette. A job with Porsche Motorsports took him to California, but he soon returned to the East Coast where he had family and jobs first with Brumos Porsche, then with several Porsche racers. He met Kachadurian in 2010 and began working for him restoring and maintaining his racecars from Russo’s shop in Delaware.

The Mirage arrived at Russo’s shop in 2016 with a target to show it at Amelia Island in March 2017. It was a mighty challenge. The car sat for a long time, and it had suffered many poor repairs. The story of the restoration is best told by Russo:

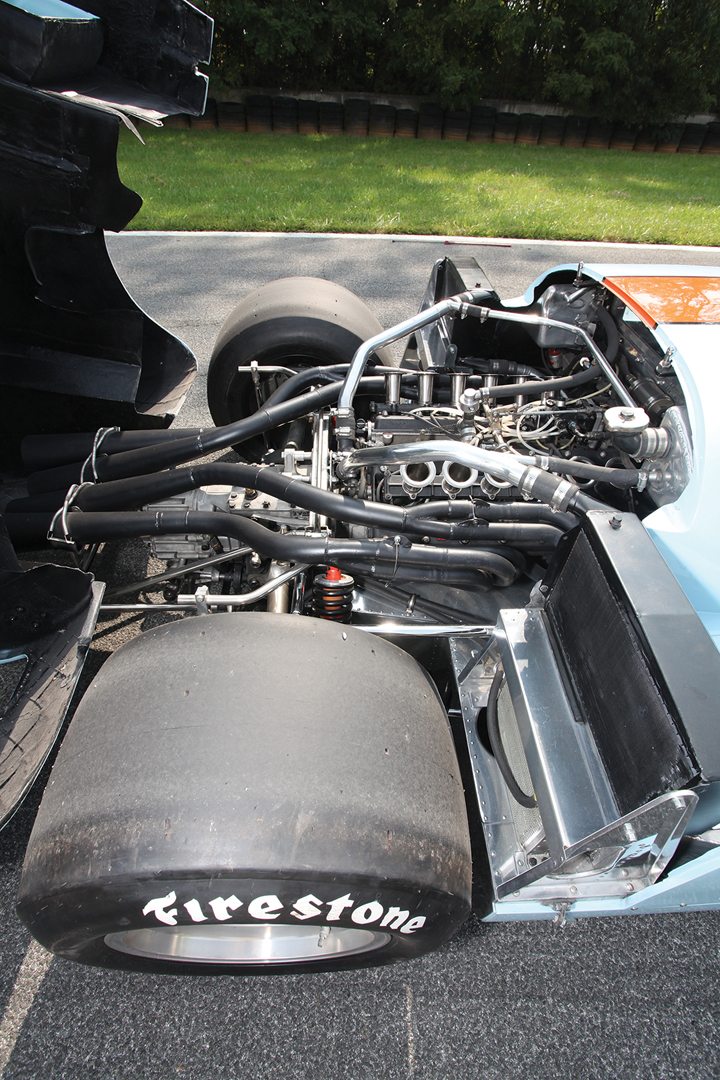

“The restoration was conducted with the emphasis on originality and authenticity. Every effort was made to use the original components of this vehicle with only refreshing where possible. The chassis is original, as are all suspension components. The fiberglass body is also original, but has been completely repaired, reinforced and repainted. Much time and effort was spent [on] the underside of the body to repair cracks, delaminations and weaknesses through the use of fiberglass cloth and epoxy resin. Additionally, the topside of the body was stripped of paint and all cracks and delaminations were repaired. All body lines and panel gaps were corrected prior to the application of single stage, catalyzed paint in the original Gulf Blue color. Both the orange and black stripes were applied by paint, as original, as opposed to the use of contemporary vinyl graphics. Correct graphics from the 1969 Nürburgring 1000K race were applied in the correct location and size. New door windows, headlight covers and rear window were manufactured to replace the original cracked and discolored components. Wherever possible, original hardware was wire-wheel cleaned and black oxided to retain originality/authenticity. The original gearbox was disassembled, checked and reassembled with new gaskets. The two-valve V12 BRM engine was given a top end refresh with lapped valves, ultrasonic-cleaned heads, new seals and repainted cam covers and other components. Previous owners had changed out components that were period incorrect, such as (stainless steel) braided lines and yellow Mallory plug wires, but these have been replaced with items that duplicate as close as possible the components that were originally fitted to this chassis. All fuel system plumbing was re-fabricated to original black hoses, replacing the vintage incorrect SS braided hose. Wheels of the proper offset and original design were sourced to properly fit the Nürburgring widened body.”

Still there were little details that were challenging. Side marker lights had to be found—exact duplicates were found from a British road car, possibly a Triumph. The car had license plate lights, but they were in bad shape—new ones were found that were for a Sunbeam Tiger. Windshield squirters came from an MGB, and the clutch slave cylinder was from a Lotus Cortina. A cam bearing cap bolt was stripped, but a bolt of seemingly the same size would not fit. The mystery was solved by a machinist —the bolt was specifically made for BRM, and it was slightly smaller than a normal 3/8” bolt. Russo shook his head and said, “Why? Because they wanted to?”

Then there were the challenges with the engine installation. Russo had to have help with this car, saying that it was the most difficult car he has ever worked on. “If I do an engine change on a Porsche 962, a car I’m familiar with, we can do it between the warmup and the race. This car (the engine) takes about two days to take out.”

Cam timing had Russo puzzled. “Duration on the cams is 330°, so the valves are essentially never closed. When the car cranks, it sounds like it has no compression because the valves are open. The exhaust valve opens at 90° after the explosion and stays open until 60° after TDC. The intake valve opens at 65° before BDC and closes at 82° or 87° after TDC. When I first cranked this thing over, I thought there was no compression, but a compression check showed only 60 psi. The leak down test was good, so I called (BRM Specialists) Hall and Hall. They don’t even check compression because of the valve overlap. With an 11,200 rpm redline, the valves have to be timed like this to get fuel into and out of the cylinder.”

Despite the short deadline and the challenges Russo faced with completing the restoration, the car was ready for, and attended, the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance in March 2017. The car is beautiful in its Gulf Racing colors. It is a little different than most Gulf-liveried cars—the body stripe does not spread out across the nose of the car, as it does with many other Wyer cars. Instead, it is a consistent width from nose to tail.

Driving Impressions

I am usually a little anxious when I’m preparing to drive someone’s very rare automobile. The anxiety has lessened quite a bit with experience, since there are many similarities among road cars. But it has been many years since I had driven a racecar, and then they had been quite a bit less powerful than a Mirage with a three-liter BRM F1 engine. When it was finally set to meet at Summit Point Raceway in West Virginia, the date was two months before I was scheduled to have a total hip replacement. So I was particularly concerned with what I would have to do to get into the Mirage, not to mention how much help I’d need to get out of it!

I took a good look around the car before changing into my driving booties, and it looked tight, especially for a guy with a bum hip. But Russo said it was deceivingly easy to get into the car, so I changed into my booties and got ready to slip into the Mirage. The routine was to put your left leg on the seat, support your body with your right hand on the radiator opening, get your right leg inside and your butt on the sill, then shift over into the seat, sliding your legs under the steering wheel. Russo was right! It was way easier to enter than many road cars I’ve driven for Vintage Roadcar. Extracting myself was by doing it all in reverse, and I needed no help when it was time to get out.

Once inside, I was impressed with the comfortable driving position. The seat was firm but with enough padding, the steering wheel was right where I like it, and my right hand fell onto the shifter without having to move my elbow. Compared to what we see on TV during an F1 or sports car race, the cockpit is incredibly simple. There are no buttons or knobs on the steering wheel, no paddles, and just enough gauges to tell you all you need to know about the car. Directly ahead is the tach. Just to the right are water temperature, oil temperature and fuel temperature. To the left are oil pressure, ammeter and fuel pressure. Really, what else do you need?

It is right-hand drive, but I once raced a right-hand drive car, a Lotus 11 LM, long ago, and I’ve driven a number of right-hand-drive road cars. So, I was not concerned about being on the “wrong” side of the car. And, the shifter was on my right, as it should be in a real racecar. One big difference between the Mirage and my long gone Lotus was the contact patch of the tires. One rear tire on the Mirage had considerably more rubber on the ground that all four of the tires on my 11.

Starting the Mirage simply requires remembering the sequence you’ve been told. First, turn on the power switch located on the firewall behind my right shoulder. Next, turn on the main switch on the dash to the right of the steering wheel. Next turn on the fuel pump switch to the left of the steering wheel. A red light will come on, then wait for the fuel pressure to come up to between 100-120 psi of fuel pressure, and hit the starter button below the main switch. We had done the on-track photography of the car, so the engine was warm and started immediately.

The ZF gearbox has a “typical Porsche racing shift pattern,” a 1 + 4 pattern with reverse above first with a lockout. I was instructed to push the clutch completely down to the stop. The engine was still being broken in, so I was told to shift it slow. The Mirage doesn’t like to be below 4500 rpm, so I should ease the gas up to full throttle and run at 6000 rpm.

I found that I had to slide down in the seat to be able to get the clutch all the way to the stop—I could have used something behind my back, but once under way, I didn’t even notice it again. Getting under way was another story. I stalled the car three times, because I was too easy on the gas.

Summit Point reminds me of a small Road America. There is a long, uphill main straight past start/finish, then a slight downhill to a sharp right-hand Turn 1. Down the hill through some curves, to a sharp left, then the Carousel, a couple curvy straights, up the hill to the last turn, then the long straight again. As I pulled out of the pits, I was easy on the gas, accelerating slowly and making sure I could find all the gears. As I went into Turn 1 for the first time, I found that the gears weren’t as easy to find going down as they were going up. I carry a recorder so I can talk to myself while driving the car, and I could hear myself saying “Whoa, whoa, whoa,” as I sorted out Turn 1 the first time. The first lap was at moderate speed so I could make sure I could find all five gears. Then the recorder noted that I said “Oh My God,” as I went up the full main straight for the first time—you could hear the smile in my voice. What great acceleration, even using only half the available revs—remember, the engine was very newly rebuilt. The next few laps were just fun! The car is very stable, it turns in nicely, and has good grip. Steering is surprisingly light, the brakes work very well. If I had been able to take the car for two or three times as many laps, I know I would have been braking much deeper into the corners, but that day was the car’s first outing at a track, so caution dictated.

The Mirage is so pretty, it’s such a joy to drive, and it performs so well, it is a shame that Wyer was seduced away from continuing its development by Porsche. Then again, it’s possible that Wyer would not have had as much success with the Mirage, as he did with the Porsches. As it is, Kachadurian has a very rare and pretty racecar that is a ton of fun to drive. How can that be bad?

Body: Two-seat, closed coupe, fiberglass reinforced with carbon fiber

Chassis: Aluminum monocoque with rear subframe

Engine: BRM 60° V12 mid-engine, longitudinally mounted; aluminum alloy block and head, two valves per cylinder, DOHC

Displacement: 2998cc/182.9cid

Bore/Stroke: 74.6mm (2.9 in)/57.2mm (2.3 in)

Lubrication:Dry Sump

Induction: Normally aspirated, Lucas fuel injection

Power: 315 bhp/312 KW @10,500rpm

Suspension: Front – Double wishbones, coil springs over shocks, anti-roll bar, Rear – Reversed lower wishbones, top links, twin trailing arms, coil springs over shocks, anti-roll bars

Steering: Rack and pinion

Brakes: Ventilated discs

Gearbox: ZF 5DS25 5-speed manual

Drive: Rear wheel drive

Weight: 750 kilograms/1654 pounds

Wheelbase:2400 millimeters (94.5 inches)

Track, front:1490 millimeters (58.7 inches)

Track, rear:1490 millimeters (58.7 inches)

Wheels, front:10.5×15

Wheels, rear: 15×15

I would like to thank Gary Kachadurian for allowing me to profile his great car, Cory Slifka for providing some excellent photographs taken on Amelia Island and Bob Russo for arranging for me to drive the Mirage, instruction on driving the car and for providing the information about the restoration. If you would like to read more about Wyer’s Mirages, I recommend Gulf-Mirage 1967-1982 by Ed McDonough.

Click here to order either the printed version of this issue or a pdf download of the print version.