1988 Jaguar XJR9 & 1991 Jaguar XJR12

Almost all of Jaguar’s competition effort in the post-war period became directed at a single target, winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans. It was an effort that was immensely successful, and having done it once, Jaguar waited for a period of years and came back and did it again. The two cars you see here, the Tom Walkinshaw-run Silk Cut XJR9 and XJR12, were part of this second attack on Le Mans, and are a key part of the tale.

The early days

Photo: Mike Jiggle

The XK120 Jaguar that first appeared in the late 1940s was designed to bring attention to the new post-war XK engine range. However, the company was rather taken by surprise when it was so favorably received, and buyers quickly lined up to order one. The supply couldn’t keep up with the demand and William Lyons was concerned that the cars needed to be kept in the public eye while production was increased. Thus the experimental department prepared cars for a variety of competitions and the cars were raced by privateers. In 1950, three of these cars ran at the Le Mans 24 Hours, and one was as high as 2nd before retiring. The other two finished the race and it was at this point that Jaguar decided to develop a car capable of winning at Le Mans.

The new car was the XK120C—C for Competition—though it soon became forever known as the C-Type. In 1951, Peter Walker and Peter Whitehead brought the C-Type across the line first at Le Mans. This was the start of a remarkable period for Jaguar. The racing section of the experimental department built, prepared and raced C-Types, D-Types and even MkVII saloons from 1951 until 1957. After winning again in a C-Type in 1953 with Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt driving, the effort then focused on the D-Types. While the C-Type was a versatile car, the D-Type was designed entirely for Le Mans and tended not to do so well on different types of circuits. The D-Types were victorious at La Sarthe in 1955, 1956 and 1957.

Jaguars faded from the long distance scene after 1958 when the engines were limited to three liters, which did not suit the XK design at all. There were still many Jaguar successes in touring cars with the 3.4 and 3.8. In 1960, with the new E-Type imminent, Briggs Cunningham ran Jaguar’s E2A at Le Mans. It was essentially a D-Type with the independent rear suspension that was to appear in the E-Type. This was not a successful effort, though the lightweight versions of the E-Type that appeared for racing were. In the mid-1960s an experimental mid-engine car—the XJ13—appeared. It was not a well-funded effort and was put aside and then was written off in a crash during filming in 1971, though it now has been rebuilt.

The new era

Photo: Pete Austin

Jaguar’s fortunes in competition ebbed and flowed in the years when it was part of British Leyland. In the mid-1970s, Bob Tullius in the USA became Jaguar’s American racing arm when he made the XJ-S very successful, winning many races between 1977 and 1981. In 1980, John Egan had been appointed either to improve Jaguar’s position as a company or close it down. He had a strong belief that competition could be used to improve the company image and that the heritage of the past could be revived.

It was during this period that Egan met up with former British saloon car champion Tom Walkinshaw, who was a talented engineer, brilliant strategist and a very thorough organizer. Tom wanted to make the XJ-S successful in Europe, and Jaguar supported his efforts to race with Chuck Nicholson through 1982. In the USA, Tullius and his Group 44 company had convinced Egan to support a plan to build a sports prototype, the XJR-5, which appeared in August. Egan was there to see the car debut, then returned to England to watch Walkinshaw win several races. Jaguar was on its way back, and sales reflected the success. Tullius’ XJR-5 was sent to Britain for Jaguar to test with Derek Bell in early 1983, and Walkinshaw was present at those tests. Tom finished 3rd in the European Touring Car Championship for drivers in 1983 with the XJ-S, and in ’84 won the title.

Thus at the end of 1984, with Tullius having returned Jaguar to Le Mans with promise, though without success, the American arm would now concentrate on IMSA events in the USA and Tom’s TWR team would run the European arm for the sportscar effort, and both TWR and Group 44 would be at Le Mans in 1985. Walkinshaw would build a “European version” of the XJR-5. Incidentally, Tullius called his car the XJR-5 simply because it was his fifth racing Jaguar.

Walkinshaw takes command

Photo: Pete Austin

Tullius ran two cars at Le Mans in 1985, with unspectacular results. The TWR XJR-6 was nearing completion, but would not appear until August at Mosport in Canada. Adorned in dark green with white stripes, the two cars were impressive, and though Martin Brundle led, his car retired and he took over the second machine, shared with Mike Thackwell, and they finished a solid 3rd behind two works Porsches. The Tony Southgate-designed cars did three more races that season, with a 2nd in Malaysia a good indication of their promise.

For 1986, it was thus relatively easy to convince Gallahers International to put their Silk Cut brand of cigarettes on the Jaguars, though that meant the traditional green livery would disappear. In the USA, Tullius continued but had less fervent support from Jaguar, which increasingly was seeing the TWR operation as the key to future success. Both teams had one victory each against the might of the Porsche 962s.

The TWR Jaguars looked even more promising in 1987. They won for the second year in a row at Silverstone in May. Then it was announced that in 1988 TWR would run both the European and American operations. The American base would be managed by Tony Dowe and Ian Reed, who became part of the Silk Cut team at Spa where the car they were engineering took a clear win. In 1987, the XJR-8 scored a 1st and 3rd at Jarama, 1st and DNF at Jerez, 1st and DNF at Monza, 1st, 2nd and a DNF at Silverstone, 5th and two DNFs at Le Mans, DNF and 4th at Norisring, 3rd at Hockenheim, 1st and 3rd at Brands Hatch, 2nd and 4th at the Nürburgring, and 1st, 2nd and 4th at Spa. Ending the season at Fuji with the top two places, Jaguar won the team championship and the drivers title went to team driver Raul Boesel.

XJR-9 and XJR-12

Photo: Pete Austin

The two cars you see here came onto the TWR/Jaguar scene in 1988, and would play a large part in the team’s fortunes. Both of them started life as XJR-9s, but one would evolve into an XJR-12 and carry on until 1991.

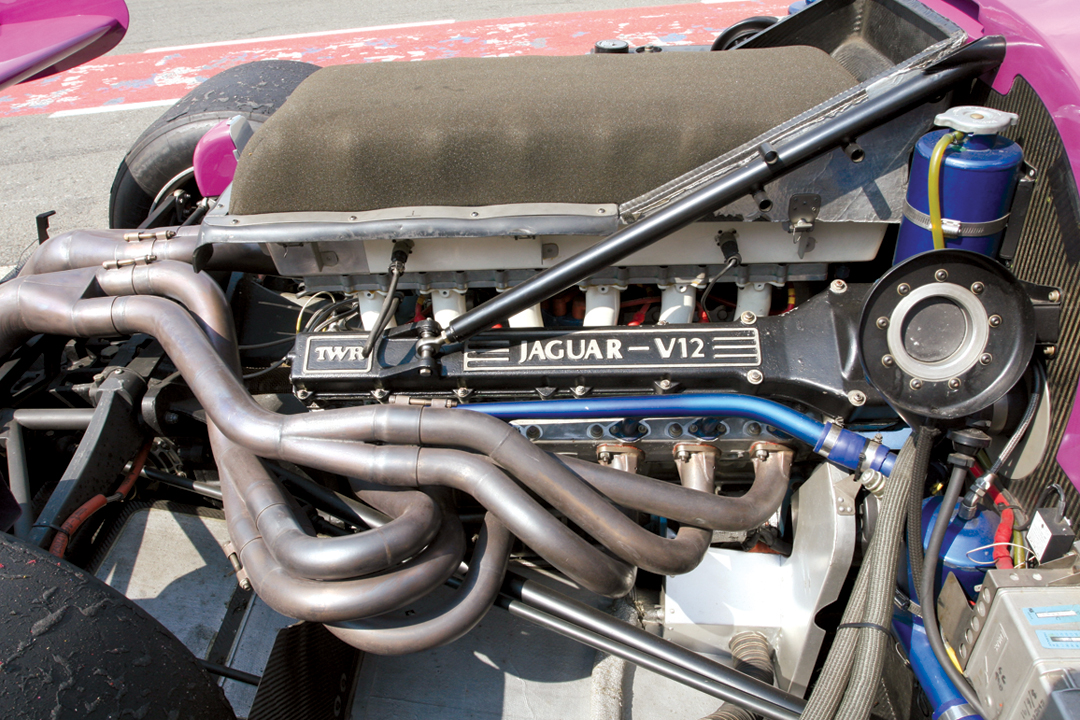

It’s important to understand the scope of what the TWR operation had become. Having achieved many successes in European Touring cars with the XJS, TWR developed the 12-cylinder, 24-valve, normally aspirated stock-block engine into the first of a series of prototype cars that would vary as the team took on a wider brief in Group C and GTP Prototype racing. The first Tony Southgate-designed XJR-6 appeared in July 1985, and this would be the first of many V-12 cars that would be progressively upgraded annually, becoming the XJR-8 in 1987, the XJR-9 in 1988/89 and then the XJR-12 from 1990 onwards.

The XJR-9 that appeared at Daytona at the beginning of 1988 was an improved version of the XJR-8. It had a 7-liter Jaguar

V-12 that had been based on the original production 5.6-liter XJS unit. This was a fuel-injected engine where emphasis had been placed on fuel efficiency to meet the strict Group C rules of the period. Southgate had designed a strong carbon fiber monocoque that was aerodynamically very advanced.

Photo: Chas Parker

Walkinshaw and Jaguar’s team, based in Valparaiso, Indiana, opened the 1988 IMSA season at Daytona with an impressive victory. Three XJR-9s—188, 288 and 388—were kept in the USA for the 14-round IMSA series. They did not win another race, but had a number of very good placings. The Electramotive Nissan team turned out to be the main competition for Jaguar, though Porsche took the Manufacturers Championship by sheer weight of numbers.

In Europe, the World Sportscar Prototype Championship started at Jerez in Spain in early March. TWR entered three cars in the familiar Silk Cut livery of white, gold and purple—chassis 187, 488 and 588. Driven by John Nielsen, Andy Wallace and John Watson, 187 was an updated XJR-8 that had three wins the previous season, while 488 was a new car in the hands of Johnny Dumfries and Jan Lammers, and 588, also new, was driven by Martin Brundle and Eddie Cheever. The car you see on these pages is 588, although in its later dark purple colors having become an XJR-12 slightly later in its life. Though the two new cars were 2nd and 3rd on the grid, they both went out with failed transmissions and the older version finished 2nd behind the Mercedes of Schlesser.

A week later the Schlesser/Baldi Sauber Mercedes was on pole again at Jarama. A lot of improvements were made back in the UK to gearbox parts, which were then flown out to Spain. Though the Mercedes led, its tires were not as durable as those on the Jaguars, and Brundle and Cheever surged past with Nielsen/Watson 3rd, after Dumfries/Lammers spun off. Chassis 588 was now on its way to becoming the most successful of the Silk Cut XJR-9s.

TWR ran only the two new cars at Monza in April, and they could not match the Mercedes in qualifying. Both Jaguars were slow off the line and the race was a battle between Mercedes and the Klaus Ludwig Porsche 962. However, as their fuel got critical, Brundle slid past late in the race to lead until the finish. Now 588 had won again as 488 once more spun off. At Silverstone a month later, 588 was up to 2nd in qualifying, and Brundle and Cheever led most of the way to take a fantastic win. After encountering problems, 488 was replaced by 187 for the race, but it didn’t finish. The Mercedes and Porsches couldn’t match the race pace of the XJR9.

Another crack at Le Mans

Photo: JDHT

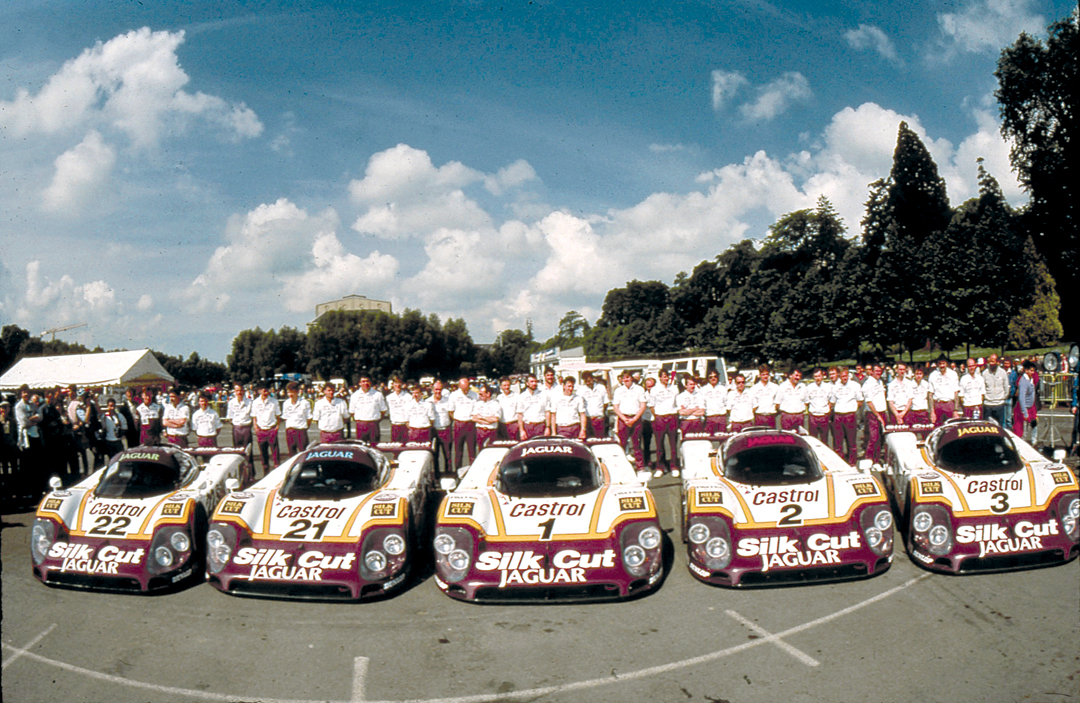

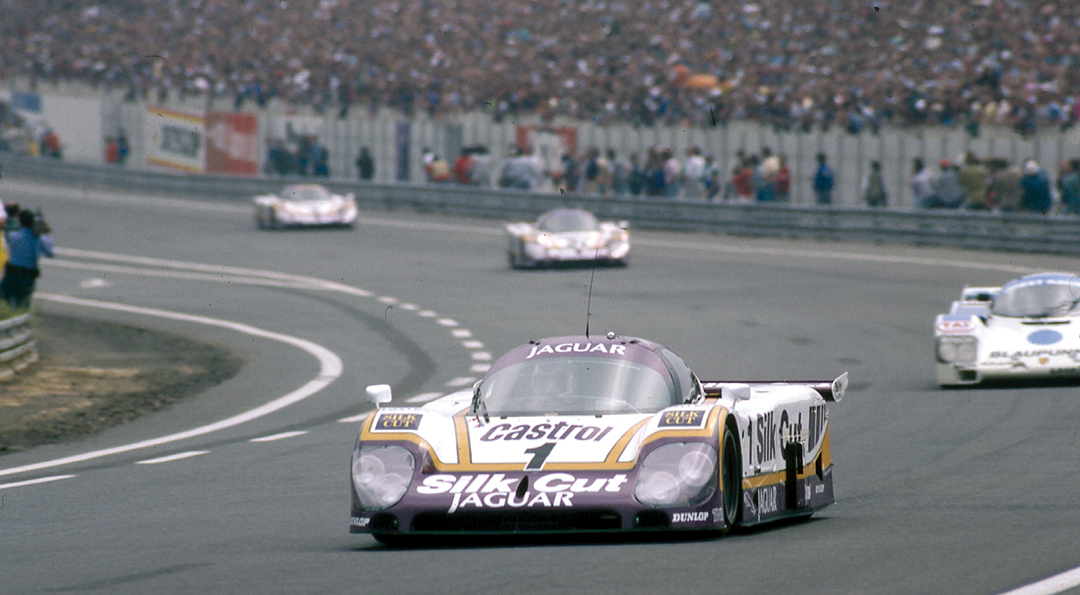

Then came Le Mans. The Walkinshaw plan had been a three-year strategy: learn, practice and then win. It worked.

TWR ran five cars—488 and 588, and 186, 188 and 287—all of which had been modified to XJR-9LM specs especially for this race. Walkinshaw believed in strength in numbers, and there were many Porsches, though the Mercedes team was withdrawn after a practice crash. The Porsches were quickest of all and ran as a three-car train in the early stages. It was Lammers and teammates Dumfries and Wallace in 488 who took the fight to Porsche, running 2nd for much of the time before taking over for a historic win. Chassis 186 was 4th, 188 16th, and the other Jaguars retired, including “our” 588, which had a head gasket fail. Immediately, 488 was retired to the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust Museum. Ironically, Le Mans had been the only race it had managed to finish!

A month went by and the Championship continued at the Brno circuit in Czechoslovakia. Serving as a T-car was 187, with 588, and another new machine, 688, appearing for the first time. This latter machine, 688, is the other car you see here, still resplendent in its original Silk Cut color scheme.

Photo: JDHT

Walkinshaw was very popular at Brno where he had won in touring cars, and was known then—and now—as “Major Tom.” In the race, 588 and 688 finished 2nd and 3rd to the Mass/Schlesser Mercedes after encountering serious understeer. These two cars and 187 were back on duty when the team came home to Brands Hatch for Round 7 toward the end of July. In terrible, wet conditions they only managed 6th, 4th and 8th on the grid. Brundle, Wallace and Nielsen worked hard to get into the lead with 588, while Dumfries and Lammers chased them in 2nd with 688 until a wiring fire dropped them to 4th. The other car had engine problems and retired.

Mercedes won the Nürburgring race that consisted of two 500-kilometer heats. Cheever and Brundle in 588 were 2nd, with Lammers and Dumfries 8th. Mercedes dominated at Spa with 688 2nd and 588 retiring with fuel pick-up woes. In October it was off to Fuji in Japan, where wet weather greeted the teams for the third race in a row. There was a big field, and Lammers and Dumfries were 6th on the grid in 688, just ahead of Brundle and Cheever in 588. A blown tire sent Lammers into the barriers after only 35 of the 224 laps, but in spite of seven Porsche 962s, it was a race between Jaguar and Mercedes. Jean-Louis Schlesser drove like a man possessed to attempt to take the drivers title, but he failed as Brundle and Cheever drove a superb race and won.

The Mercedes got their revenge six weeks later at Sandown Park in Australia, as 588 and 688 could not accelerate as quickly as the German turbo cars out of the many slow corners, and finished 3rd and 4th. However, TWR Jaguar had won the Manufacturers Championship and Brundle became Champion Driver…a very good year.

1989…business not quite as usual

Photo: Mike Jiggle

What had become clear to TWR and Jaguar in 1988 was that Peter Sauber’s Sauber Mercedes project, which had started out as a small operation, had gotten more and more professional and had attracted considerable support from the Mercedes factory. Hence while the 1989 season got underway in Europe and in America with the 1988 cars, TWR was working hard on new turbocharged cars—the XJR-10 for the IMSA series and the XJR-11 for the World Sportscar Championship.

In the background in 1989 was Jaguar’s decrease in profit, and hence John Egan undertook and finalized the merger with Ford. Race lengths were cut in half for 1989, which worked against the endurance capabilities of the V-12 engine. Le Mans would continue, but would not be a championship event.

At the first race at Suzuka in April, numerous Japanese cars joined Sauber Mercedes and Porsche as Jaguar opponents. To illustrate the change, Geoff Lees and former Jaguar driver Johnny Dumfries were on pole with a Tom’s Toyota with a similar car 2nd. Jan Lammers and Patrick Tambay put 588 3rd, but Nielsen/Wallace were back in 12th with 688. The “Silver Arrows” won, while 588 ran out of fuel with a lap to go, and 688 managed 5th.

Photo: Pete Austin

At Dijon, neither 588 nor 688 finished—which had not happened since 1986—588 running out of fuel again while 688 blew a tire, and a Porsche beat the Mercedes. At Le Mans, 287 and 288 joined 588 and 688 and these cars took four of the top eight places on the grid. While 288 held 2nd at four hours, it dropped back to finish 8th, as 588 pressed on to take 4th, though it had led for five hours until losing an hour with gearbox problems. Both 688 and 287 retired.

The best result of the year came at Jarama where Lammers and Tambay were 2nd in 588 and Nielsen/Wallace 6th in 688. At Brands Hatch the new XJR-11 was on pole but finished 5th. John Nielsen had a huge accident in 688 when the brakes failed and that was the end of the car’s racing career, until its recent restoration. After serving as the T-car at Nürburgring, Donington and Spa, 588 finished 6th in the final race in Mexico in late October. It was a very disappointing year, and all hopes rested on the turbo cars for 1990…mostly.

Transformation

Photo: Pete Austin

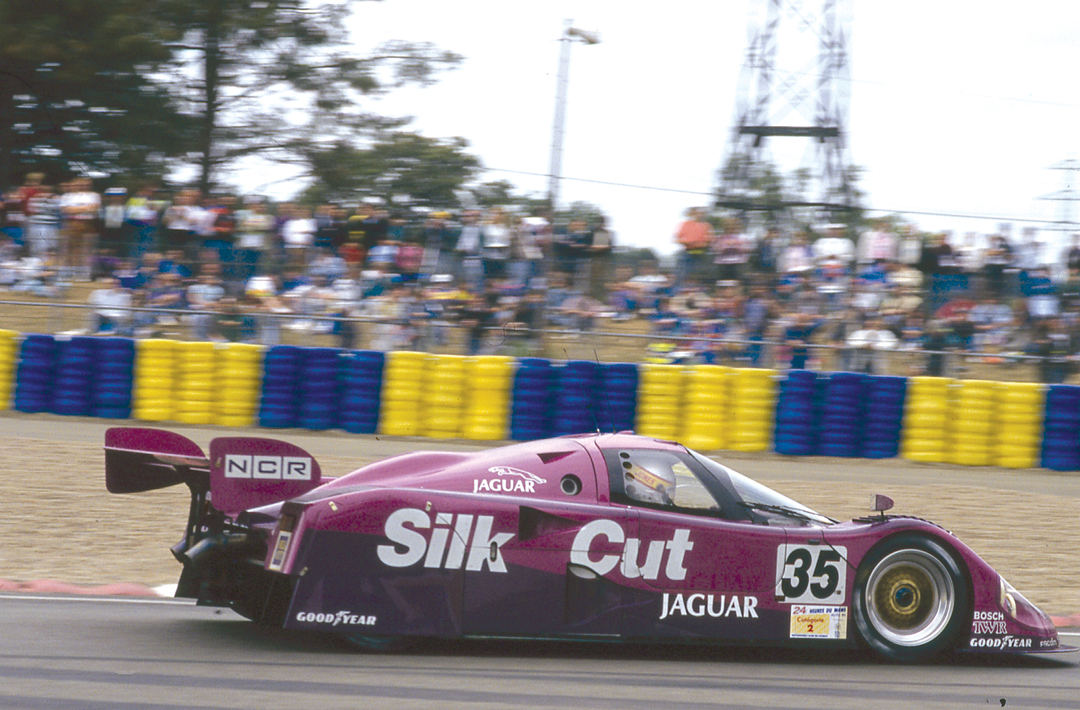

The XJR-11s looked more promising in 1990 as they took 1st and 2nd at Silverstone in May. Though Le Mans was a non-championship race, it was very important for Jaguar to do well at La Sarthe. Thus they put the turbo cars aside and entered four “atmospheric” cars. One was 588, which had now been rebuilt as an XJR-12LM with the new chassis number 990. This is the car you see on these pages in the later, darker colors. The former IMSA chassis 288 became XJR-12LM 1090. Both 190 and 290 had been built for IMSA racing, but now also became Le Mans-spec cars.

All four cars ran near the front. Sadly, 588, with Brundle, Ferte and Leslie, retired at 7.30 a.m. with a broken water pump. Brundle joined the three drivers in 1090, which went on to a sensational victory, and chassis 290 followed it into 2nd, a fine gift for the about-to-retire John Egan. A year later, 990 (formerly 588), covered itself in more glory by finishing 2nd at Le Mans with Davy Jones, Michel Ferte and Raul Boesel. It then sat quietly at TWR until being updated for the 1993 Daytona 24 Hours where it appeared as an XJR-12D in Bud Light colors, driven by John Andretti, John Nielsen and David Brabham. It qualified 3rd but retired with an oil leak. That was its last race in period, and it was a rather timely end as manufacturer support for Group C racing would begin to wane and a great era came to an end.

Driving the Silk Cut Jaguars

Photo: Pete Austin

Both 588/990 and 688 remained in the TWR Museum. Jaguar had withdrawn from the World Championship series in 1992, and the Daytona effort was their last prototype event. TWR continued with the IMSA program, having, of course, developed the XJR-10, XJR-11, the XJR-16, which was the best turbo car, the XJR-14 and the XJR-17.

The cars were bought by Gary and John Pearson from the collection when the company went into receivership, and have subsequently been prepared for a return to historic Group C racing. It was under their supervision that the cars appeared at a recent BRDC test day on the brand-new Grand Prix circuit at Silverstone, so a very serious double treat was in store as we prepared to try out both cars on the track that hosts the British Grand Prix.

Photo: BRDC Archive

With Gary in 588/990 and myself ensconced in 688, we set off for some exploratory laps to find our way on the new surface and to get to grips with the complexity of a Group C car. I’ve had a few Group C experiences to date, and they have all been very different. The first was in the Lancia LC2 where I had the classic newcomer’s dilemma of how to drive a car against one’s instincts? After a few low-speed trips over the gravel trap, I got the message: you don’t slow down for corners. A Tiga at Spa was easier to manage, but I still hadn’t got used to: brake very late, keep throttle and brake on, turn into corner with revs and don’t lose any speed. Scary! A Porsche 962 that wouldn’t steer didn’t help, but that was more a car problem.

So, here we were with two very fast Jaguar Group C machines. Gary Pearson is well known for driving these cars very fast, and he surprised me by saying that this pair was not that difficult to get used to. Fortunately he was right. Having had a few laps in VR contributor Peter Collins’s newly purchased Alfa Giulietta Sprint Veloce, I could see that the new layout was fast and interesting, but not complicated. The cars have all the period Group C technology and are very similar in many ways. After the warm-up, I was put in the XJR-12, which is 588 that was an XJR-9 updated to XJR-12 Le Mans specs. It now wears the livery in which it appeared at Le Mans in 1991.

Photo: BRDC Archive

This car had benefited from the TWR development period, and the intention was that it should have every modification that would make it something you could take to Le Mans, would be straightforward to drive, and would be capable of winning. There was an emphasis in the TWR program on cars being driver-friendly, which grew from Walkinshaw’s own experience as a driver. Though this car bristles with technology, most of it is related to the demands of endurance racing—lights, signaling, etc. Basically, it is a very comfortable environment with the main gauges and rev counter behind the wheel. The tach reads to 8000 rpm, but we were going to stick somewhere around 6000-6500 rpm. The carbon fiber seat was just about right, but the six-point harness is necessary to hold you firmly in place. Starting was straightforward, and the 5-speed ’box magic—so smooth and fluid—very driver-friendly.

My concerns about the trickiness of Group C cars disappeared quickly. Gary was right, this car is easy to drive. I was warned to warm the tires up for a lap, otherwise it might be “a bit pointy,” which I assumed meant it would go straight off! But it did warm up rapidly. I had not managed to get the mirrors adjusted correctly, but soon discovered the car to be so quick that no one would be likely to be coming up behind it. In fact, in Gary’s hands, it was the quickest car on the day.

Starting was easy; no finicky revving needed, just a steady 2000 rpm and it was off and running. With everything up to working temperature, I was amazed how easy it was to start using a fair proportion of the engine’s available 750 bhp. The torque was astounding—no other word for it—as well as smooth and manageable. In fact, within two to three laps I was having the luxury of experimenting with the gears on various corners. If you came down the pit straight in fifth, there was the choice to use fourth or fifth in Copse. Fifth was good, though not quite flat. I’m not that brave! Rushing down to Maggotts in top, it was down to fourth for the Becketts complex, and that’s hard in fourth to get out onto the long Hangar Straight quickly at high revs in fifth. Again, I eased off at Stowe, though not as much as usual as the grip was terrific through that very fast bend. Down to Vale taken in third keeping the power on and up to fourth through Club. Then comes the new part of the Silverstone circuit. Instead of going left at Abbey, there is now a very fast sweeping right-hander. At first I braked and went down to fourth, coming out much too slow. The car inspires confidence and it was fabulous to be able to thunder into that corner in fifth, lift a bit, and then sweep through keeping the throttle down through the next slight left and then very hard on those huge brakes for the tight right before the left hairpin, throttle down, using second or third, up the box and flat left back onto the old club straight.

Photo: BRDC Archive

That new bit of road was wonderful in this car. Unlike some Group C set-ups, the Jaguars are relatively soft, with a good bit of “feel,” though no roll. This XJR-12 was remarkably “tight,” no rattles, no tempermental behavior from the rear with the power on, just straight down to the business of going fast. I did manage to give it too much throttle in the new hairpin left in second gear, and the back started to slide but it was instantly catchable. It was absolutely at its best pounding through the fastest corners at very high speed. A true Le Mans car.

Both cars had the feel of machines that would be civilized to drive in a 24-hour race. They must have been harder in sprints on some of the tighter tracks, but given long straights and fast bends, it would not have been hard to stay in these cars for two, or three, or four hours.

I then swapped back to 688 in its original XJR-9 configuration. For the most part it was very similar to 588/990. The gearbox was not quite as slick, the gears being a bit further apart. I almost selected first instead of third on one occasion, but you soon become aware of those quirks. Coming down from fourth to third required more attention, and couldn’t be rushed. It was clear to me how significant these cars were by the amount of attention they got just sitting waiting to go out.

Starting procedure was the same with both cars: start the pumps and injection system, then the ignition and the starter at the same time, giving 2000 revs worth of fuel and off it goes, all quite smoothly. I could see better out of this car, and was pretty happy as a Jaguar driver by now. Although 688 didn’t seem to have quite the punch of its sister car, and the torque might be a bit less smooth in delivery, there were only small differences. The handling was predictable, very reassuring, lots of grip and could go through Copse in top with a bit of a lift. The handling was helped by good Dunlops on 18-inch rims.

This had been a magnificent test of two very important cars from a fascinating period, one of them the best car of its type with many successes.

SPECIFICATIONS (both cars)

Engine: V-12 at 60 degrees

Capacity: 6.995 liters

Power: 700 to 750 bhp @7200 rpm

Bore and stroke: 94 mm x 84 mm

Compression: 12.0 : 1

Torque: 828 Nm/611 ft lbs @5500 rpm

Top speed: 245 mph

Valvetrain: 2 valves per cylinder/sohc

Fuel delivery: Zytek Fuel Injection

Chassis & body: Kevlar and carbon monocoque

Front suspension: double wishbones, pushrod-activated coil springs over dampers Rear suspension magnesium uprights, titanium coil springs over dampers

Steering: Power-assisted rack and pinion

Brakes: Ventilated carbon discs all around Gearbox March TWR 5-speed

Weight: 881 kilograms (approx)

Wheelbase: 2780 mm

Track: 1500 mm front and rear

Resources

We are very grateful to Gary Pearson for his generosity and assistance in running the two cars, and to the BRDC for the use of the Silverstone circuit and for their help with our efforts. Thanks also to John O’Keeffe of Jaguar and the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust.

Thurston, L. TWR Jaguar Prototype Racers, Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust Ltd., Coventry, England 2003