The J. Frank Harrison story

Given today’s racing environment with its multi-million-dollar corporate budgets, it can be hard to imagine a time when private individuals paid these expenses. Wealthy enthusiasts such as Lindsey Hopkins (a Florida investment banker), John Edgar (a California industrialist), Joe Lubin (a California tractor parts dealer), and Tony Parravano and Frank Arciero (both owners of California construction companies) spent substantial amounts of money on cars raced on their behalf.

Besides the satisfaction of participating in the sport, most of these owners did not get much in return, certainly no great monetary gains. Prize money tended to be a drop in the bucket. Team-owner Briggs Cunningham was different; he raced himself, but as a manufacturer and subsequent car importer, he also had his own financial interest in mind: win on Sunday and sell on Monday. The same was true of Johnny von Neumann. These motor racing sponsors were an eclectic group of personalities, covered by the popular Fifties term “sportsmen.”

One particular sportsman stood out. Beginning as a small-time entrant in SCCA racing in the late Fifties, he progressed to USAC-sanctioned professional road racing in the early Sixties and, at the same time, provided a Formula One car for the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. He entered a Lotus on the USAC Championship car circuit a month before Colin Chapman and his works team. Then he became a constructor, in both sports car and Indy-car competition, while racing Formula Juniors himself. His name was J. Frank Harrison Jr., of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Harrison spent a vast amount on his hobby over the 10 years he participated in motor sports. He owned the Coca-Cola Bottling Company, founded by his grandfather in 1902. Before the turn of the century Coca-Cola was a fountain beverage sold at soda counters in drugstores for 5 cents a glass. Coke became the worldwide brand it is today through the innovative idea of marketing the drink in reusable bottles. Harrison’s grandfather, one of the first independent bottlers, bought the Greensboro-based franchise for North Carolina’s Piedmont region and sold the new delicacy in a slogan-decorated horse-drawn carriage.

From home-base Chattanooga, the Harrison family continued to expand the bottling business, although Frank, the racing team owner, never capitalized on his Coca-Cola connection. An intensely private man, he avoided interviews and, when asked about his background, said he was an industrialist running a glass factory. After Frank became a constructor, his cars were always called Harrison Specials, without any reference to the drink to which the family business owed its success.

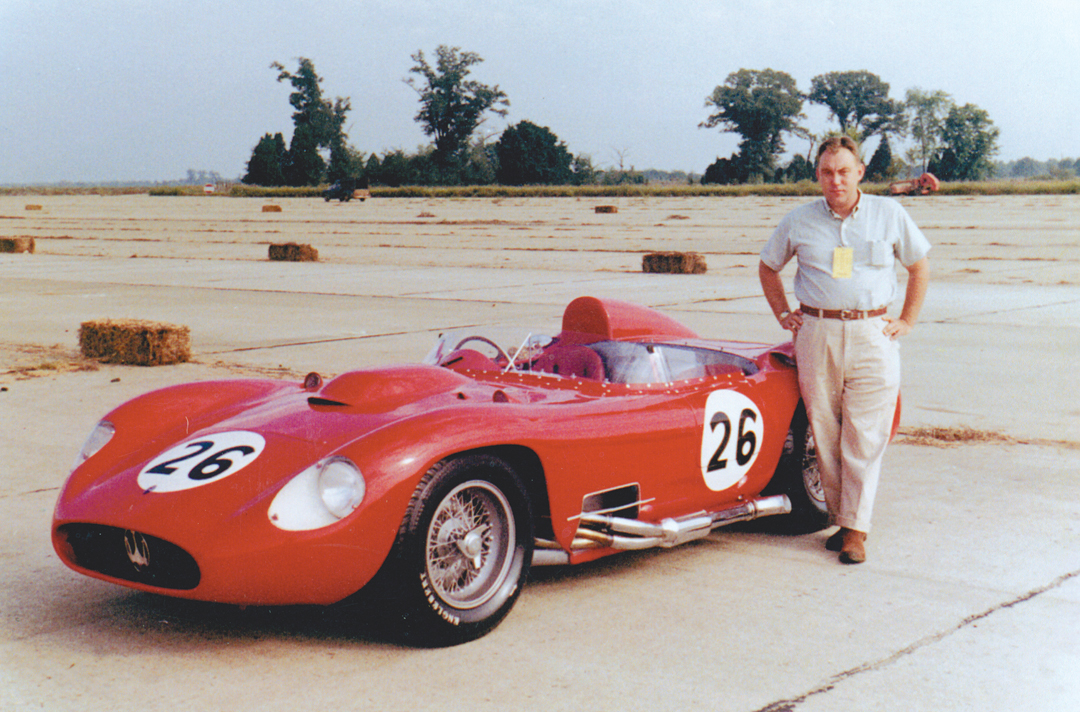

Harrison became interested in sports cars at a young age when he fell in love with a neighbor’s MG-TD. Soon he bought his own, followed by a modified Jaguar XK-120. His next purchase was a Devin-bodied, flathead Ford-engined backyard special used in a few local hillclimbs. By 1957, however, Frank was ready for more exotic purchases. He attended the Sebring 12 Hours, won by Juan Manuel Fangio and Jean Behra in a works Maserati 450S. A few months later, Carroll Shelby beat the Cunningham D-type Jaguars as he took a similar Maserati to victory at the SCCA National at VIR, in Danville. Harrison was watching again and decided he wanted a 450S as well. He placed an order with the regional Maserati agency, owned by Dick Hall, Jim Hall, and Carroll Shelby in Dallas, Texas. The red Maserati cost him $16,500, including $320 to cover the expense of four additional Borrani wheels. Harrison’s 450S, chassis 4510, was the last one built by Maserati.

Testing the Waters

After its completion in Modena in late January 1958, Jim Hall delivered the 450S to Chattanooga in March. At 29, Harrison became the youngest owner of the most powerful sports racer in the world. To top it off, he bought an enclosed transporter just like fellow 450S owners, Jim Kimberly and John Edgar. The truck provided a seating area on the roof for extra comfort and track visibility. Two full-time mechanics took care of his Maserati: Bill Warren, a local wrencher, and Bert Kemp, an Englishman with Maserati experience who came from the Hall brothers/Shelby agency. Later on, when the team advertised third-party jobs such as competition tuning under the name Competition Cars Inc., John Tatum joined them as the third mechanic.

Without much racing experience to speak of, Frank was clearly out of his league with the 400-bhp beast, which generally carried his favorite race number 26. He enjoyed watching racing, but left the actual competition to some of his Chattanooga friends, Dan Clippenger and Walt Cline. They ran the Maserati in local SCCA regionals, just for fun. In May, Clippenger, a Volkswagen dealer and amateur racer of small production cars, scored the first win for Harrison at Chester, South Carolina. In spite of two spectacular spins he came back to beat C. K. Thompson’s Jaguar D-Type. Second-driver Cline owned W. M. Cline Company, a photo-finishing business with 35 camera shops around the southeast. He was a former Corvette driver more used to big-engined cars. Cline took the wheel at Courtland, Alabama, in August. Victorious in the preliminary, the 450S was withdrawn from the feature because of low oil pressure. In October, at Dothan, Alabama, Cline captured 2nd in the preliminary behind E. D. Martin’s Testa Rossa, but retired with a broken oil line in the main race. Since Cline’s wife was strongly against his racing, he had to do so in secret. One day she visited the Harrison garage, where the 450S was being prepared for Walt’s next outing. In a fit of fury she attacked the car with a lead hammer, damaging its Weber carburetors. Cline, deciding that domestic peace was more important, quit racing on the spot.

By 1959, the younger of the Hall brothers in the agency became involved as well. Although Jim had handled Harrison’s order in 1957, he had never raced a 450S. At Coffeyville, Kansas, in May, Hall ran his supercharged Lister/Chevy in the preliminary and won. In the feature he switched to Harrison’s 450S to win once more, finding he liked the Maserati better than his Lister. At Harrison’s invitation, Jim raced it again in October in two Alabama events. At Courtland, he won the sprint but had to pit for new rubber in the feature, which dropped him from 1st to 3rd. At Dothan two weeks later, Hall used harder Dunlop tires, but twice E. D. Martin’s new Tipo 61 Birdcage Maserati beat him. At Nassau in December, the Texan finished 5th in the Governor’s Trophy and 12th in the Nassau Trophy. Harrison realized the 450S was reaching the end of its competitive life.

Chattanooga may have been a backwater when it came to sports car racing, but Frank was well connected. He developed a relationship with David Brown and Reg Parnell of the Aston Martin team, offering to pick up their cars with his transporter and take them from New York to Sebring for the 1959 12 Hours. As a result, the team invited him as an honorary guest at Sebring and Le Mans. Later that year, he provided Parnell with the design of an air jack used on the Sumar Specials of his friend Chapman Root in Indianapolis racing. Root was a fellow Coca-Cola bottler from Terre Haute, Indiana, whose family had won the classic green Coke-bottle-design contest in 1915. Aston Martin used the air jack design in the season-ending Tourist Trophy, where they secured the 1959 World Championship. However, the English factory had no new cars to offer. After witnessing Martin’s performance with the new Birdcage, both Hall and Harrison placed their orders for a Tipo 61, although they had to wait well into 1960 before the cars were delivered.

A Pair of Birdcages

Another friend of Harrison’s, chief starter Jesse Coleman, put him in touch with Jim Jeffords, fresh from racing a Camoradi Birdcage at Le Mans in June 1960. Jeffords had bought the fastest of the three Camoradi Maseratis, chassis 2451, the famous Streamliner, for the USAC-sanctioned Road America 200 at the end of July. The deal was based on cash-on-delivery at O’Hare Airport, but Jeffords had a problem; he did not have the cash for his $17,000 purchase. Still waiting for his own Birdcage to be delivered, Harrison offered to buy the Streamliner and sponsor Jeffords for the rest of the season. A relieved Jeffords accepted the offer.

Refurbished at Maserati after Le Mans, the Streamliner arrived at O’Hare two days before Road America 200 practice. No time was left to change the Camoradi paint job. Jeffords merely painted his name on the rear fenders and, in gratitude for his help, added Coleman’s as “driver’s agent.” Harrison was not present at Road America, but Jeffords took the Streamliner to a storybook victory and claimed a $3,650 winner’s purse.

By mid-July, the factory finally completed Harrison’s original Birdcage order. Unlike his Streamliner, the new chassis 2467 was a conventional model, painted red. Frank entered both cars in the September Road America 500 sanctioned by the SCCA, leaving the final selection up to Jeffords. Choosing the red Birdcage and inviting Jim Hall as his co-driver, Jeffords took the Maserati to an immediate lead. When Hall took over after 40 laps, the Harrison car was still in front. Suddenly, the exhaust manifold cracked. It threw flames at the pedals, frying Hall’s feet and boiling the car’s brake fluid. Chassis 2467, undrivable, was retired on lap 50.

After a first taste of the winner’s spoils in professional racing in July, Frank continued his focus on the two remaining USAC races, at Riverside (Times Grand Prix) and Laguna Seca (Pacific Grand Prix). Thanks to earlier victories in the Riverside Examiner Grand Prix with a Camoradi Birdcage and the Castle Rock International 100 with a Meister Brauser Scarab, points-leader Carroll Shelby had no trouble convincing Harrison that he would be a perfect fit for the red Birdcage. All he had to do was finish 4th or 5th to capture the championship. As per his contract, Jeffords returned to the Streamliner, now stripped of all paint and its aluminum body highly polished.

For the October Times Grand Prix, Shelby’s car had better gearing for the long Riverside straight, but Jeffords beat him to 4th overall. Bill Krause won the race in the latest Tipo 61 Maserati. Jeffords’s efforts won him $1,100, while Shelby received $750 for 5th overall. One week later at Laguna Seca, Jeffords dropped out early when the Streamliner began losing oil, while Shelby’s heat results (5th and 4th) were good for a combined 2nd-place finish. The 1960 USAC Championship was Shelby’s, much to the delight of car-owner Harrison.

This high point was the end of Shelby’s career as a race driver. He popped four nitroglycerin pills to combat heart problems during Riverside’s 200-miler. At Laguna Seca, the number rose to seven pills. Shelby had long realized his health was in decline and that he had to retire from competition. As a result, when the Nassau Speed Week came along early in December, Jeffords had first choice again among the Harrison Birdcages. For the Governor’s Trophy, he selected the red Tipo 61 and made an aggressive bid for the lead on the opening lap, but the Birdcage made contact with George Constantine’s Aston Martin DBR2, spun sideways, and was T-boned by Pedro Rodriguez’s Testa Rossa. Jeffords’s switch back to the Streamliner for the International Trophy did not improve his luck; he retired with a disintegrating exhaust system while running 5th.

Open-Wheel Pursuits

Frank always insisted that his drivers treat his equipment with care, and consequently was not pleased that his red Birdcage had suffered substantial damage. After Nassau, he and Jeffords parted ways. For 1961, he hired Fred Gamble, one of the original Camoradi founders, to pursue the SCCA DM title with the Streamliner. Considering the strong opposition offered by fellow Birdcage drivers Walt Hansgen, Roger Penske, and Gus Andrey, Gamble did very well. He scored 2nd-place overall finishes in the Marlboro and Cumberland Nationals, and collected enough points for 2nd in DM class behind Hansgen by mid-season; but things were not going well within the team. Gamble’s Tipo 61 suffered from numerous chassis and exhaust breakages, and he complained of a lack of preparation, blaming team-manager, Sierra “Smokey” Drolet, before leaving the team after Meadowdale in July.

One of the distracting factors for the team mechanics may have been Frank himself. In May, he finished the SCCA drivers school at Courtland, Alabama, to begin his own competition pursuit. His first rides were in two Formula Junior Coopers, one bought from Briggs Cunningham in February, the other from the factory in April. Harrison took the cars to wins at Courtland and the Chimney Rock Hillclimb that season, while Smokey Drolet ran the second Cooper.

At the same time, Harrison seemed determined to corner the market on his favorite car, the 450S Maserati. He already owned the red chassis 4510; then acquired blue-and-white-striped chassis 4509 from Ebb Rose in September 1960. Lloyd Ruby, of Wichita Falls, Texas, had raced chassis 4509 as the Micro-Lube Special in 1959. Harrison used neither of these cars in competition in 1961, and actually had his red 450S converted for street use by installing Corvette disc brakes and a 4-speed gearbox. His third 450S, the white chassis 4508 originally owned by Temple Buell, was a different matter. Harrison bought the 5.7-liter car in April 1961 following its victory in Jim Hall’s hands at Mansfield, Louisiana.

Ruby, with 450S experience, was invited to run the car in the Hoosier Grand Prix at Indianapolis Raceway Park in June, the first round of the 1961 USAC Road Racing Championship. He won the first heat over Ken Miles (Porsche RS61) and Augie Pabst (Scarab), who trailed Ruby by 47.2 seconds. During the intermission, the Harrison team gave Pabst two new front tires because the Scarab owner, Harry Woodnorth, had brought no spares. In hindsight, this act of generosity was not a good idea. Pabst started Heat 2 on a tear, while Ruby spun the big Maserati on the first lap, giving up 10 positions. Lloyd made up the loss and was running 2nd when he received the “EZ” sign.

The Harrison team fully expected to win the event with Ruby’s 1st- and 2nd-place finishes, anticipating that Pabst, if he lasted, could at best have 1st- and 3rd-place heat results. Nobody had consulted the rulebook, though, which dictated that overall positions were based on aggregated times rather than heat positions. Pabst crossed the finish line after faster times on each lap; he had made up his entire deficit plus 7 seconds, a margin that dropped Ruby to 2nd overall.

Chassis 4508 made only one more appearance, with Bill Kimberly at Courtland in July. At the start of one of the preliminaries, Kimberly blew its gearbox, and the car soon joined the other two 450S Maseratis in Frank’s private collection.

By October, when Watkins Glen hosted the 3rd U.S. Grand Prix, the lure of entering Formula One racing overtook Harrison. He entered one of his No. 26 cars, a slightly used, 1.5-liter, Lotus 18-Climax bought from Jim Hall shortly before the race. Harrison had the car, chassis 907, repainted gold and blue and invited Lloyd Ruby to drive for him again. Choosing an Indianapolis driver for a Formula One event threw off a number of pundits.

Today primarily remembered as one of the most hard-luck drivers in Indy 500 history, Ruby had an extensive midget background beginning in 1946. Even more helpful on a track such as the Glen was his experience as a professional road racer with various Maseratis owned by Rose, for whom he was chief mechanic between 1957 and 1960.

In a rare interview I had with Harrison in 1997, he reminisced on his driver selection: “Ruby had worked for Ebb Rose for a long time. We met casually and I liked him. I liked his sense of humor and mannerisms. We just got together. Ruby wasn’t only a good driver, he was one heck of a mechanic. He also was a motorcycle racer in the old days, raced around the boardwalk tracks and so forth. He had been around for a long time. Ruby was good. Keep in mind, he had been road racing for Rose who had a 450S Maserati. Ruby could get out of a car and tell a mechanic pretty quickly what he needed to do to set the car up. Jim Hall was the same way. That was one of Ruby’s greatest assets.”

Ruby did not disappoint at Watkins Glen. Although he qualified the Lotus on the last row, he soon moved up the field. On lap 6 he was running 11th, ahead of other privateers such as Peter Ryan, Roger Penske, Hap Sharp, and Jim Hall, as well as Walt Hansgen and Olivier Gendebien. From lap 30 until lap 49, Ruby was firmly in 9th overall, having won the skirmish with Joakim Bonnier’s works Porsche. A 14-minute pit stop on lap 50 to repair its throttle linkage dropped the Harrison Lotus back and eventually the car retired on lap 76 with a broken magneto drive.

In spite of the disappointing Formula One result at the Glen, Harrison had found himself a long-term driver and close friend. Since Ruby had professional status, he could only campaign for Frank in USAC-sanctioned events, but he was a perfect fit for the state-of-the-art car that his sponsor had ordered in England earlier in the year. It was a new 2.5-liter, Lotus 19-Climax, chassis 954, delivered to Chattanooga at the end of October and again painted gold and blue.

Luring Eisert from Arciero

The Harrison Lotus 19 made its first race appearance in 1962, during the February Daytona Continental. Frank’s transporter brought the three-year-old Streamliner as a back-up car for Ruby, who never made it to the start of the 3-hour race. During practice, the Lotus 19 behaved as it had with various other drivers (Stirling Moss, Dan Gurney, Augie Pabst): It caught fire. In his haste to get out of the car, Ruby stuffed it under the Armco barrier, resulting in body and suspension damage. Because of his burns, Ruby could not practice the Birdcage, and Harrison decided to call the whole thing off. Aware that the Streamliner was pretty obsolete by now, he sold both it and his Nassau-damaged red Birdcage in a package deal to Don Skogmo of Minneapolis.

The new season brought much activity for Harrison’s Formula Junior fleet, now consisting of the two Coopers, an older Lotus, and two Lolas, after an earlier model was wrecked by Smokey at Courtland in October 1961. Frank, Smokey, and Don Johnson, a third Chattanooga driver, pursued the SCCA Regionals in the southeast. Chimney Rock in May brought another victory for Harrison’s Cooper, but at Savannah later that month, while racing with his new national competition license, he spun his Lola and hit Chuck Cassel’s Porsche 550RS. Smokey took the other Lola to victory in Saturday’s preliminary, but lost the brakes on Sunday. More victories followed for the Harrison Lolas at Courtland in June and September, and at Chimney Rock again in November. In between, Frank and Smokey co-drove the 1.5-liter Formula One Lotus 18 in a 3-hour race at Columbia, South Carolina, where they dropped out around mid-race while running 2nd overall.

The fast money was on Ruby and the 1962 professional circuit, although a full schedule of racing roadsters and dirt cars in USAC’s National Championship events limited his Harrison rides. In April, Ruby and the Lotus 18 appeared at the Bossier City Pipeline 200 in Louisiana, the first USAC road race of the season. The 18 was equipped with the 2.5-liter Climax unit from Harrison’s Lotus 19 sports racer. Trouble in practice forced a last-minute qualifying attempt on Saturday. Ruby’s time of 1:41.01 was good for the pole, until it lost to Gurney’s Arciero Lotus 18 in Sunday morning’s qualifying. Ruby ran 2nd to Gurney for the first six laps of Heat 1, but then dropped out after blowing a head gasket. During the 2nd heat, he captured the lead from Roger Penske’s Cooper T53-Climax on lap 10, but two laps later the Lotus lost all oil pressure for another DNF.

Harrison skipped the next two rounds of the USAC Championship at Indianapolis Raceway Park and Pacific Raceways, but Ruby was back in the Lotus 19 in the October Times Grand Prix at Riverside. During the summer, Harrison had scored a major coup by hiring chief mechanic Jerry Eisert away from Frank Arciero, for whom Eisert had prepared the Lotus 18 and 19 for Gurney. Ruby qualified 7th with 1:37.2, a split-second behind Masten Gregory in BRP’s Lotus 19-Climax, victorious twice that season at Mosport. The Harrison Lotus ran well among a strong field, and by lap 50 Ruby had climbed to 4th overall after passing Bruce McLaren’s 2.7-liter works Cooper Monaco. Unfortunately, eight laps later he coasted into pit lane with no gears left in his Colotti box.

One week later, in the Pacific Grand Prix at Laguna Seca, Ruby excelled by putting the Harrison 19 on the front row, second fastest with 1:13.2, outqualified only by Roger Penske’s controversial 2.7-liter Zerex Special. This was Ruby’s first time at Laguna Seca, which was considered a driver’s course, making his performance even more remarkable. At the end of the first heat’s opening lap, just before the pits, the Harrison 19 got away from its driver, and although no damage was done, Ruby had to let the entire field pass before he could resume the chase. At the finish he had worked himself back to 4th place, on the same lap as winner Gurney in the Arciero 19. Heat 2 was a delight for every USAC fan in the crowd. The flying Ruby caught and passed Penske on lap 12, and did the same to Gurney on lap 27. At the finish, the Harrison 19 had a 35-second lead over Penske, who won the event on aggregate. Ruby was awarded 2nd place and $2,000 for his heat win, which, incidentally, was 2 mph faster than Gurney’s.

The Nassau Trophy in December produced another burst of speed by the Harrison 19. Rather than ship the car by sea as most competitors did, J. Frank decided to fly it in with a DC3 rented in Fort Lauderdale. In addition to the 19, a pair of motorcycles and numerous toolboxes, the plane carried Harrison, Ruby, Eisert, Drolet, and Nedra Ware, another Chattanooga fan and occasional Porsche racer.

Ruby made a good start but spun early, damaging the Lotus bodywork. He then ripped off the loose sections, mostly the passenger door and a large part of the right front fender, and continued. Having lost four spots and under a tropical rainstorm that almost drowned him in the exposed cockpit, Ruby battled back to capture 2nd overall. The effort ended in vain when on lap 48 the Climax engine lost its oil pressure. Ruby and Eisert pushed the 19 back to pit lane with one of the motorcycles, but the Harrison car was done for the day.

Tackling the Championship Trail

Harrison continued competing in the Mid-Atlantic SCCA Regionals, running his Lolas in Formula Junior and Formula Libre (with a 1.5-liter Ford engine), winning at Chimney Rock in May and Savannah in November. A new addition to his fleet was a Lotus 23, which he raced once at Courtland in July, only to let Don Johnson campaign it for the rest of the season. In our interview he recalled: “In hindsight, I personally enjoyed driving an open-wheel single seater. I started off with a pair of Coopers with all-aluminum bodies. They were old team cars with small engines in them, Formula Juniors. I went to driver’s school in 1961 and raced those cars for a while. Then, through Reg Parnell, I met Eric Broadley and that group. I bought a pair of Lolas that were Formula Junior types and ex-team cars. Both of them were aluminum. Later I ended up with a third Lola with a newer fiberglass body. We would put in bigger Webers and these cars would flat fly. I loved to do hillclimbing in North Carolina. There was something about those little cars that was really fascinating. Maybe it was part of the reason I got more and more turned on by single-seaters and Indianapolis.

“I remember talking to Reg Parnell at times about sports cars versus single-seaters. You don’t have a lot of systems on a single-seater. That’s why I was interested in staying with those cars and getting out of sports cars completely. I never raced professionally myself. I had no desire to do so, as it was an entirely different ballgame. I did do some SCCA racing. In those days open-wheel single-seaters could run with the closed cars. I’ve got to tell you, going to these races and participating was fantastic. You’d run behind a Corvette and slip inside it, outbraking it. You’d be surprised what you could do.”

An awed crowd at Trenton, New Jersey, in April was the first beneficiary of Harrison’s love for single-seaters. The race, held on a one-mile paved oval, counted toward the USAC National Championship. The field consisted mostly of Offenhauser-powered upright dirt cars, considered ideal for this type of course. Yet Ruby and his stretched Harrison Lotus 18-Climax captured pole position with a new track record. Although A.J. Foyt led the first 10 laps of the race, from lap 11 on Ruby kept all the top oval drivers, Foyt, Parnelli Jones, Jim Hurtubise, Eddie Sachs, and Rodger Ward, behind him. It lasted until lap 40 when his gearbox broke, but Frank beat Colin Chapman and his Ford-financed works Lotus-Fords by a month in USAC Championship racing.

He recalled: “Well, it looked like those rear-engined cars had some real possibilities. We had one sitting in the shop, so why not go ahead and do what we had to do to make it legal? That’s what we did. We ran it at Trenton and we were surprised how well it ran. The mistake we made was not taking it to the Speedway that year. Speedway (wheebase) specifications were 96 inches if I remember correctly. It still had the 2.5-liter Climax engine as used at Bossier in 1962. If that Colotti gearbox had held out at Trenton, Ruby would have been all right. Later on, Eisert modified the car by installing a 289 Ford V-8 engine, and in 1965, Al Unser won Pikes Peak with it.”

Ruby ran the Lotus 18-Climax on the one-mile paved oval at Milwaukee in June and again at Trenton in July. At Milwaukee he finished 12th after more gearbox problems, while in its second Trenton appearance the Climax engine threw a connecting rod on the second lap. An interesting feature on the car were the words, in Ford script, Powered by Four, courtesy of mechanic Errol Kaufman.

Although single-seaters were his primary focus, Harrison continued to campaign his Lotus 19 for Ruby. In June the combination—for the first time powered by a 2.7-liter Climax—appeared at Mosport, Canada, to contest the Player’s 200. It was a two-heat event, with Ruby starting the first section from the back of the grid. Having flown in from Indianapolis the morning of the race after only 4 hours of sleep, Ruby did not have a qualifying time. He had never seen the track, but managed some practice laps on Sunday morning. Once the race was underway, the Harrison 19 catapulted to 2nd by lap 20, gaining on pole-sitter Chuck Daigh in the Arciero Lotus 19. Ruby took the lead on lap 34 and kept it, finishing ahead of Daigh, Jerry Grant (Lotus 19-Buick), Roger Penske (Zerex Special), Jim Hall (Chaparral), and Dan Gurney (Cooper Monaco). Alas, while pulling away again from Daigh in the second heat, Ruby’s brilliant run came to an end with only 12 laps to go; having recorded the fastest lap of the day, the Harrison 19 broke its gearbox.

It took four months for the 19 to reappear, and when it did, it had changed completely. After Mosport, Eisert had stripped the car to its bare chassis. He modified and strengthened it, keeping only the Lotus suspension parts and a few inches of its original tubes. Harrison commissioned Dick Troutman and Tom Barnes to fabricate a Zerex-type aluminum body based on drawings by Chuck Pelly, while Eisert replaced the Climax with a 4.7-liter Ford V-8. The 326-bhp engine was fairly stock, fed by four downdraft Webers and hooked up to a Colotti gearbox. This car was the first Harrison Special, entered in September’s Northwest Grand Prix at Pacific Raceways, Kent, Washington.

Ruby qualified the Harrison Special 4th on the grid just ahead of Dave MacDonald in Shelby’s equally new King Cobra, a Ford-powered Cooper Monaco. Continuing to work on the setup of the car, Ruby had the misfortune to hit oil and spin an hour before the start. J. Frank’s entry suffered bent rear-wishbone mounts and a hole in the Colotti housing. After frantic repairs by Eisert, Troutman, Barnes, and Jim Travers of Traco Engineering, the car made it to the grid with four minutes to spare, the gearbox hole sealed with Popsicle sticks and epoxy.

When the King Cobras retired early and Gurney’s works Genie-Ford pitted with engine-belt problems, Ruby won the first heat over Rodger Ward’s Nickey Cooper-Chevy and Graham Hill’s Lotus 23. During intermission the Harrison crew replaced a damaged distributor rotor, sending Ruby off at a conservative pace in Heat 2. Attrition was again high, with Gurney, MacDonald, and Grant (Lotus 19-Buick) retiring or suffering delays. Ruby and Ward had no such problems, repeating their earlier finishing order. Winning first time out with a new design pleased Harrison tremendously. Ruby’s purse came to $7,400, while Jerry Titus was so impressed that he wrote a rave review on the Harrison Special in Sports Car Graphic’s December 1963 issue.

The Times and Pacific Grands Prix in October were less successful. At Riverside, Ruby was only 8th fastest in practice, perhaps because his car’s stock engine lacked top speed. After 16 laps he had climbed to 4th overall, only to retire with clutch problems on lap 24. At Laguna Seca, the Harrison Special qualified 3rd fastest. Running 4th during the opening laps, the car slipped back after a lengthy pit stop to remedy a loose suspension arm. Ruby finished 15th overall, 10 laps down. After returning to Chattanooga, Frank sold the car to Charlie Kolb, who ran it at Nassau.

Harrison himself had a scare at the end of the season when he crashed his Lola Formula Libre at Chimney Rock. He recalled: “I went off in the Lola, hanging by a thread overlooking a little bluff. I couldn’t get out of the car because you had to raise the hood. Two mechanics came down, threw me a rope and then pulled the car up. I could only climb out after they lifted the hood.” Meanwhile, his driver Don Johnson captured the Formula Junior title in the SCCA’s Southeast Division.

Building an Indy Car

When asked in 1997 why no professional Harrison entries appeared in 1964, the team owner replied: “We took a year to build our own Indianapolis car. Eisert moved to Chattanooga for a while, but in the end we moved everything to Newport Beach, California. Jerry had a shop out there for the Speedway stuff.”

Early that year Harrison’s amateur race career came to an end. At Macon, Georgia, in April he retired the Ford V-8-powered Lotus 18. Harrison: “I nearly scared myself to death in that thing. The way the car was set up, my head was above the roll bar. As I went around a turn, she rocked up on two wheels and back, up on two wheels and back, and then kept going. That was the same type of car that Moss had his terrible wreck in. At that moment I was probably as scared as I have ever been. The roll bar wouldn’t have helped much. I was so big in those days that I had no place to go!”

After crashing his Formula Libre Lola into a tree near the starting line at a wet Chimney Rock the following weekend, Frank had had enough. A newly arrived Lotus 30-Ford, chassis 30/L/5, flexed so much that Eisert had to reinforce it with extra tubing and a steel-belly pan. Harrison’s logbooks give no indication the Lotus 30 was ever raced by his team. When Eisert returned to his California base, the Chattanooga operations were dismantled. Parting ways with Smokey Drolet, Frank gave her an unspecified sum of money and a hot new Pontiac. His old road racing cars were put into storage in Chattanooga and from then on Harrison focused strictly on Indy-type racing.

The second Harrison Special, the new 4.2-liter Chevy-powered open-wheeler for USAC racing, appeared for its first event at Phoenix in March 1965. The car had a rather wide monocoque body. Since Ruby had a prior commitment for the season, Canadian Billy Foster signed up for two races. At Phoenix, Foster retired on lap 12 with engine problems. One month later at Trenton, he came home a promising 7th overall, one lap down in the rain-shortened race.

With Foster already booked for the Indianapolis 500, Harrison hired Skip Hudson. When Hudson failed his rookie test, Al Unser was given a try, but he could not get the car up to sufficient speed to make the race. Harrison remembered: “That was a very pretty car, but it was not very quick. It had a pushrod Chevy engine. The design was Lotus-inspired. We used my Lotus Formula Junior as an example.”

For June’s Rex Mays 100 at Milwaukee, Harrison entered two cars, both Chevy-powered. Al Unser and Johnny Rutherford drove them, the former finishing 13th, nine laps down, the latter retiring due to a fire. Since Eisert had completed only one Harrison Indy racer so far, it is thought that Rutherford’s car was the resurrected Lotus 18. With Unser driving it in all subsequent Championship races, the Harrison Special’s best result was a 7th overall in the August Milwaukee 200, still four laps off the pace. J. Frank’s only highlight that season was Unser’s win at Pikes Peak aboard the heavily modified Lotus 18 with 4.7-liter Ford power.

In 1966, Unser raced for Harrison one more time, at Phoenix in March. The 1965 design was updated with a Batmobile-type rear wing, the first time a winged car had run a National Championship event, but the engine blew a head gasket in the race. Foster retired early at Trenton in April after losing the transmission, but the Brickyard promised better results. Eisert had finished a second Indy car for Harrison, much slimmer than the original design. Although Bob Mathouser could not qualify the 1965 car, a last-moment switch to Ford DOHC power enabled Ronnie Duman to capture the 33rd grid position in the latest version. Unfortunately, Duman became involved in the first-lap accident that eliminated a large part of the field, and the Harrison Special was too damaged to take the restart.

Duman remained Harrison’s primary driver until September, with a best result of 7th overall using Chevy power in July’s Hoosier Grand Prix at Indianapolis Raceway Park. Alternating between Ford and Chevy engines did not provide any improvements. Neither did a switch to new drivers, Greg Weld and Jerry Grant. It was a disappointing year for the Harrison/Eisert partnership.

The 1967 season started optimistically when Weld finished 6th overall with Chevy power at Phoenix in April. He was at the wheel of the third Indy car built by Eisert. However, Frank’s interest seemed to be waning. His team skipped a number of Championship events, including Indianapolis. Another new driver, Gary Congdon, could not get the car up to competitive speeds no matter what engine configuration it had. The last of nine 1967 appearances by a Harrison Special came in November, at the Riverside Rex Mays 300 where Lothar Motschenbacher was forced to retire his Chevy-engined car with clutch problems after eight laps. Harrison pulled out, although his designer would continue to race the cars under Eisert Racing Enterprises in 1968, with Rutherford, Peter Revson, and Canadian Ludwig Heimrath driving.

Asked in 1997 about the limited racing schedule 30 years earlier, Harrison responded: “I guess by that time we were getting ready to phase out. I just felt it was time to go. Our Coca-Cola bottling business was picking up, leaving me with less time and so forth. I got out of it completely. Getting out of racing was not my biggest mistake, but disposing of my old racecars was. I remember walking through the old shop behind the plant here in town. There were 13 cars, Maseratis, Lolas, Coopers, and Lotuses. The cars went to the West Coast and Jerry Eisert got rid of them. I don’t know to whom he sold them.”

At the time of our interview, Frank was rebuilding a car collection, starting with his first love, the MG-TD. Two military-style Hummers were featured as well, a fact he was especially proud of since at the time they were not available to the public. Paneled cabinets in his garage displayed a wonderful model collection dominated by 450S and Birdcage Maseratis in Harrison colors, and he gave me full access to his photo collection. In our subsequent correspondence, Frank always ended his letters by “With a Coke and a Smile,” and it was with great sadness that I heard this superb ambassador to motor racing had died of a heart attack in his Chattanooga office on November 26, 2002, at age 72. Today his son, J. Frank Harrison III, leads Charlotte-based Coca-Cola Consolidated operations, now a Fortune 500 company and the nation’s second largest bottler.