LYNX 1963 LOW-DRAG E-TYPE

In the Indian summer of 1961, Wolfgang von Trips was killed at Monza in the Ferrari Sharknose, and an American college student—a Trips fan—made a gesture about driving fast cars to mark his passing. He swapped his first car, a Fiat 1100 sedan, for the first sports car he saw for sale, a 1954 Jaguar XK120, and for many months, through a cold Boston winter, never put the top up and drove as if speed and high revs could bring the dead German back.

That person never told that story, and it only rose to the surface when Lynx Chairman John Mayston-Taylor showed your reporter his father’s pristine XK-120 sitting in the Lynx workshops in deepest Sussex on the south coast of England, and revealed that it was, for him, “the start of it all.” The set of German-linked Jaguar coincidences went a step further when it became clear that the car we were there to test was inspired by another Jaguar, driven by a German, the famed E-Type low-drag coupe of Peter Lindner and Peter Nocker, the car which Lindner crashed fatally at Monthléry, creating the birth of a myth and an enduring interest in these rare coupes.

The E-Type Evolution

The sad irony about Jaguar is that, as this piece was being written, it was being announced that Jaguar car manufacture at Coventry is coming to an end. The city which survived serious wartime bombing and rose again with Jaguar there to help its recovery is now suffering another attack, but this time it is the malaise which has eaten into British car-building. It is odd and heartening, then, that Lynx should still be able to produce cars which bring back the days of Jaguar’s prestige as a manufacturer and racer of great machines.

The Jaguar E-Type had its origins in the heyday of Jaguar success, in the mid-1950s when a car was being designed with new racing regulations in mind, and Jaguar’s Malcolm Sayer came up with a shapely little car with a 2.4-liter engine, the prototype E1A. The E-Type was clearly to be a production car, and it differed from the D-Type behind the bulkhead that now became a monocoque structure. The prototype first ran in 1957 and was tested in July 1958 by Mike Hawthorn. It was not quick and the work on road and racing versions slowed down, and production prototypes were not built until near the end of 1959, by which time the decision had been made to use steel in the bodies instead of aluminum. The competition prototype, to be used for testing only, the E2A, was built in January and February 1960, but American Briggs Cunningham happened to see it at the factory and persuaded Jaguar’s Bill Heynes to prepare it for Le Mans.

Ed Crawford drove E2A at the Le Mans test days in April, but Cunningham stalwart Walt Hansgen was paired with Dan Gurney for the 24 Hours and the car ran as high as 6th before several stops with injection problems, and finally a burnt piston, put them out. With a 3.8-liter engine installed on carburetors, the car came to the U.S. where the author saw Hansgen win with it at Bridgehampton, and even Jack Brabham drove it once at Riverside. More prototypes were built and tested in 1960 and there was talk of building 100 GT cars for racing. Later modifications to these might include Malcolm Sayer’s idea for a low-drag coupe, but this would not come to fruition for some time. When the production E-Type, a coupe, was launched at the Geneva Motor Show in March 1961, it created a storm of publicity and immediately became a desirable “cult car.”

Photo: Peter Collins

It was quickly decided at Jaguar, which was not going back into racing itself, to build some “improved” cars and these were sold as customer racecars, seven of them in that first batch which were immediately successful and threatening Ferraris in GT events. Both Jack Sears and Roy Salvadori have recently mentioned how nice these cars were to drive, and how quickly they got to grips with the opposition. These cars were a mix of roadsters, coupes and fixed head coupes. Towards the end of 1961, it was the intention to build a new batch of lighter weight cars for 1962 incorporating the low-drag roofline, but the plan switched to building open cars. The steel-bodied roadster which John Coombs had bought and raced in 1961, registration 4 WPD, was brought back to the factory after Roy Salvadori crashed it at Goodwood in 1962 and rebuilt with a lighter-gauge steel body. Salvadori and Graham Hill raced it through 1962 and it was again brought back to the factory in the winter of 1962–63, where it became the prototype for the famed Lightweight E-Types. The principal modifications were an aluminum body shell and engine block. Twelve Lightweights were built, of which two were low-drag coupes, and then a further low-drag car also appeared. All of these cars differed in detail from production cars and from each other.

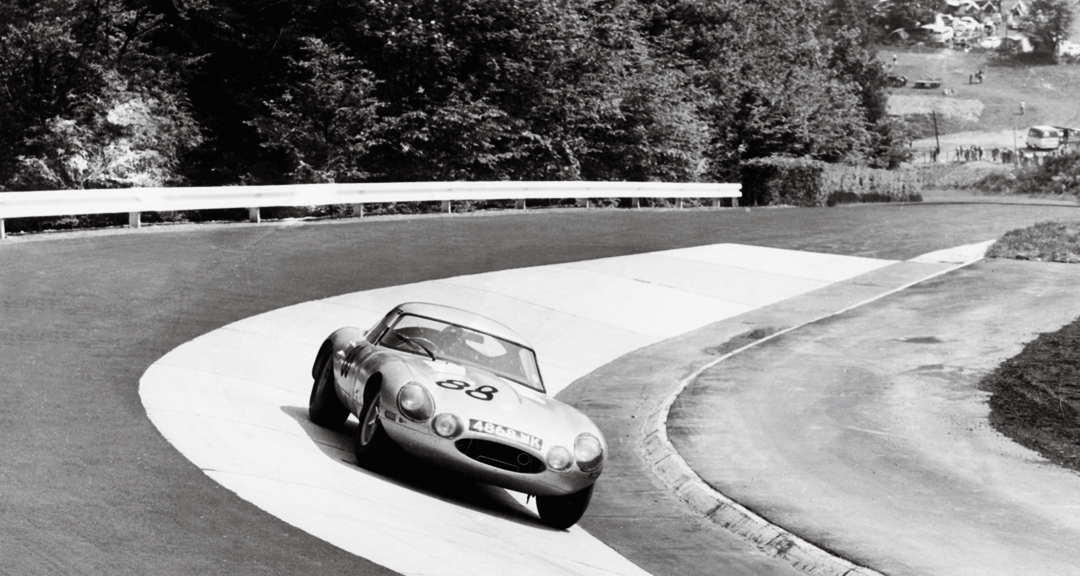

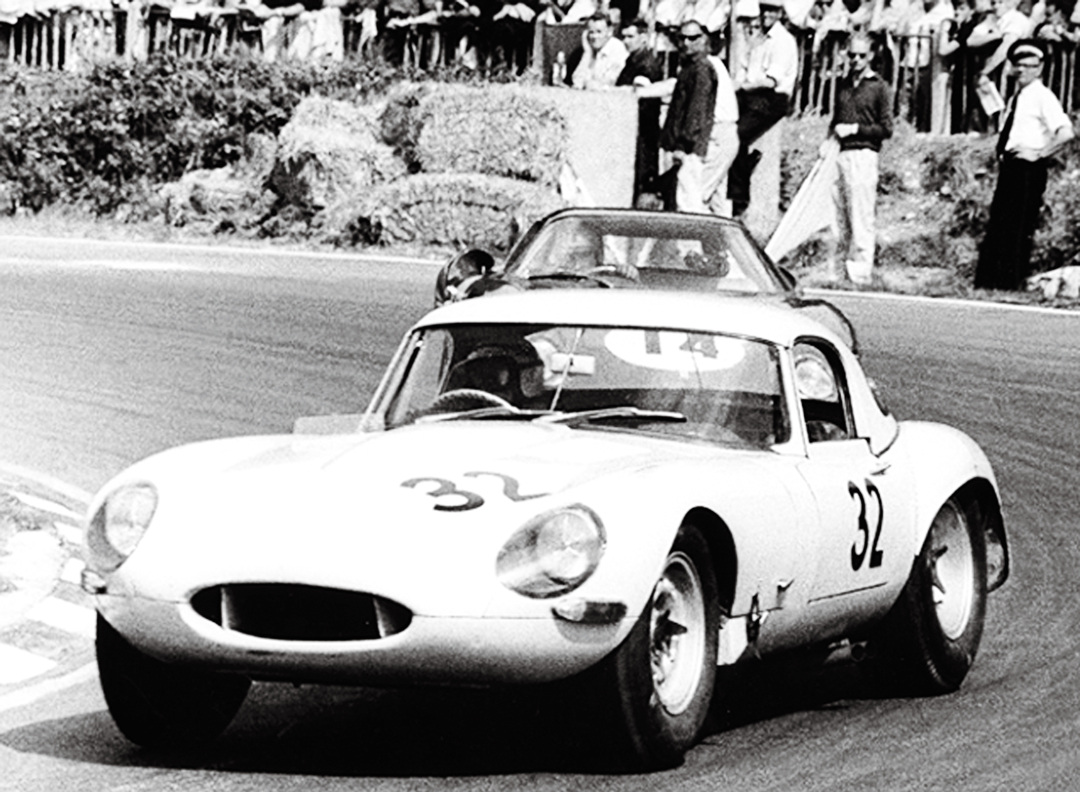

The fifth car built, chassis S850662, registration number 4868 WK, was sold to German Jaguar dealer Peter Lindner in early 1963. It retired with Lindner and Peter Nocker at the Nürburgring 1000 Km but won at Avus in Berlin. It was prepared for Le Mans 1964 with Sayer’s low-drag roof and with a steel block. It was very fast at Le Mans, but retired, and then Lindner drove it at the Montlhéry circuit near Paris, where he crashed and was killed in a terrible accident. The car’s remains were impounded by the French police and these later changed hands several times, ending up with Guy Black, who was running Lynx. The car was then carefully and meticulously rebuilt with a new monocoque and went to Peter Kaus’ Bianco Rosso Museum in Germany, where it resides today.

The sixth Lightweight, registration 49 FXN, known as the Lumsden-Sargent car, was also rebuilt after a crash with a revised low-drag body and was raced by Lumsden up until 1965. The third and final low-drag car was not, in fact, the 13th Lightweight, but was the project Malcolm Sayer was developing before the idea came along to build roadsters. This chassis, EC1001, an experimental number, lingered at the factory, but this car had a steel rather than aluminum body in low-drag form, and was bought by Dick Protheroe in 1963. This car was raced and hillclimbed for many years with the registration CUT 7. All the low-drag cars, therefore, exist and all the other Lightweights are also accounted for. The third chassis, the Kjell Qvale car which raced at Sebring in 1963 with Ed Leslie/Frank Morill, reappeared in a California garage after having gone missing for many years. This car was also restored by Lynx, and has returned to compete in a number of historic races.

The Lynx Story

Lynx has evolved from a couple of newly qualified engineers repairing historic cars out of a number of sheds to a modern, purpose-built headquarters in St. Leonards on Sea, near Hastings. The origins were in the late 1960s, and as the 1970s came, so did a demand for recreations of Jaguar C-and D-Types, and many of these cars were built, accepted for racing and road use, and are still part of the Jaguar scene.

John Mayston-Taylor, the current chairman, came onto the scene in the early 1990s when the market changed and the company went into receivership. Under Mayston-Taylor it has been rebuilt back into more than just an automotive engineering company, developing new and technically challenging projects. Lynx continues to restore and maintain historic cars, mainly but not solely Jaguars, but also has built a wide range of new vehicles: D-and C-Types, the XKSS, XJS Spyder and XJ Convertible, and the Eventer, a stylish performance estate based on the XJS.

Photo: Peter Collins

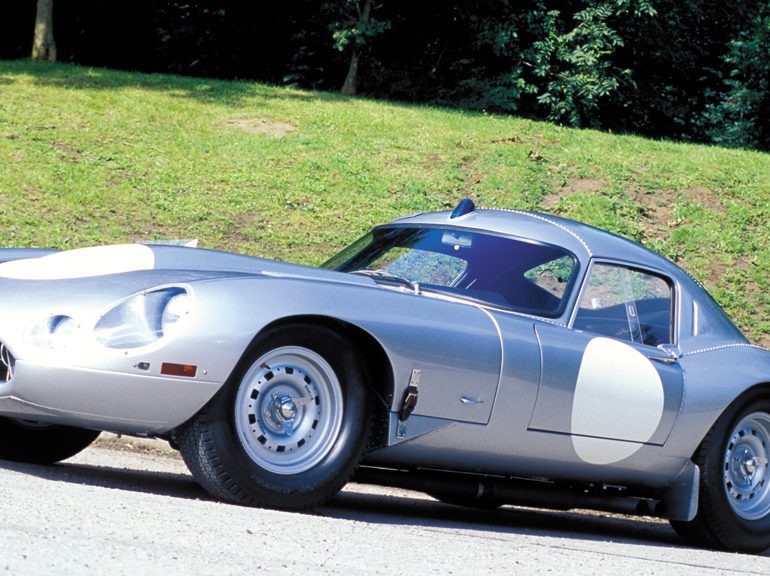

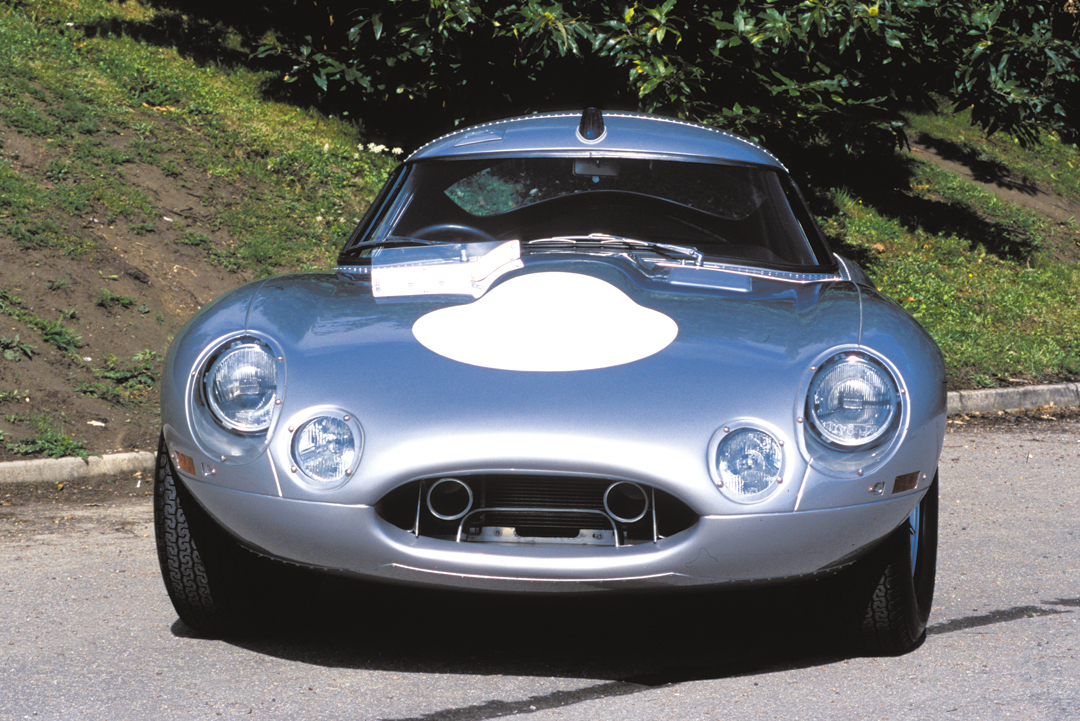

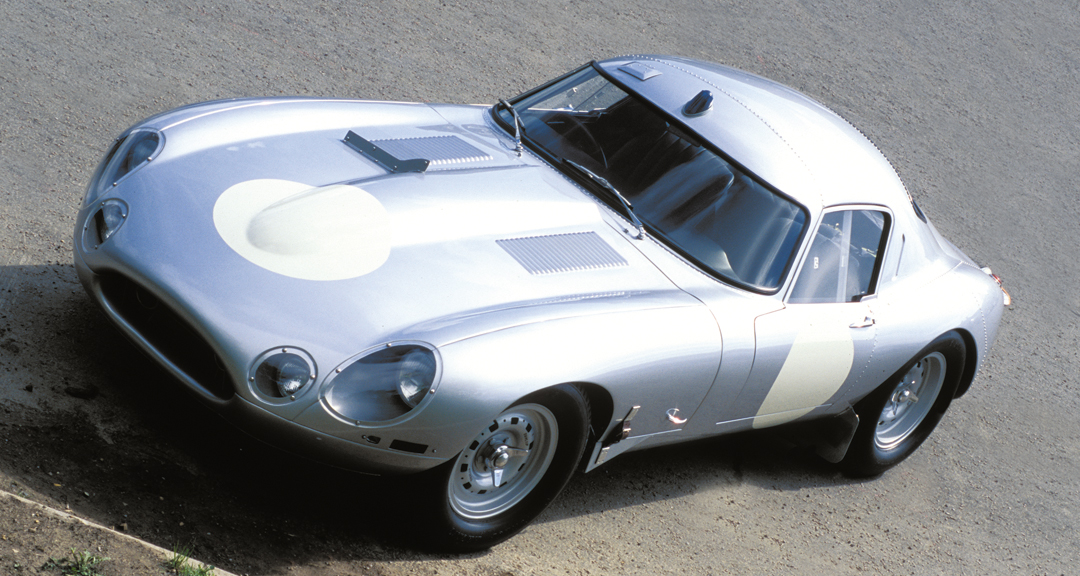

We were in Sussex to investigate their Low Drag Coupe, the fifth such model based on the 1963 Lindner/Nocker car. Lynx painstakingly rebuilt the crashed original and there, sitting high up on the shelves of the storeroom, were the roof and rear panels of that car which languished in a French police warehouse for 12 years after Lindner’s crash. It was the expertise gained in restoring and building Lightweights which brought on the Low Drag Coupe project, that and an awareness that the rarity of such cars meant that there would be customers for such a beautiful and well-engineered road and track car.

Low-Drag Coupe LE01-05

This car was built to capture the flavor of the Jaguar Lightweights of the early 1960s, with only non-visible concessions to modern safety standards and a degree of comfort and owner usability. The car is, without doubt, one of the sexiest GTs ever made, enhanced by a myriad of superb details like the exact duplication of the number and location of the body rivets, and the addition of the blue light on the roof which alerted the signal crew at night at Le Mans that their car was coming. These lights were original to a Peugeot truck and this one was found at Retromobile in Paris. Authenticity is also built in with original Dunlop Lightweight wheels from the stock built up from Jaguar’s own allocation. These wheels carry Dunlop Racing tires, 6.00M-15 on the front and 6.50M-15 on the rear.

Photo: Lynx

Though the car was built as a dual-purpose road-track machine, it looks very race oriented, with number roundels painted on in Jaguar Ivory, a racing fuel filler, and the Le Mans lighting on side and rear, though with modern halogen headlights. Well-crafted period bonnet handles and straps also add to the period feel, and again authenticity is found in the location of the exhaust on the left side, which drops down from the manifold and then goes over the chassis tubing, as in the Lindner/Nocker car. It exits behind the left-side door, providing the complete auditory experience to go with the tactile nature of the beast. For FIA racing, the exhaust is moved inside the chassis rails. The right rear has venting for the fuel pump and drilled holes to assist cooling to the rear brakes. There are venting flaps in front of the rear wheels as well. Access panels are located in the rear section to make brake pad changes manageable, and the floor dimensions can be altered to suit the height of the driver. This particular car seemed perfect to me but a six-plus footer would want to go for the larger options. I drove it with my helmet on to get the race-feel, and that meant I was a regular head-banger!

The beautiful and detailed exterior makes it hard to accept what Mayston-Taylor then showed me, a total photographic record of every aspect of the car’s building program. This included the arrival and dismantling of a complete but sad E-Type donor car of exactly the right period. This means the car is a Jaguar and is registered as such. The engine, suspension and a number of components from the donor car are stripped and rebuilt but a completely new, safe body structure is employed to achieve the strength of the performance car which is being constructed, essentially as Jaguar did it in period.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

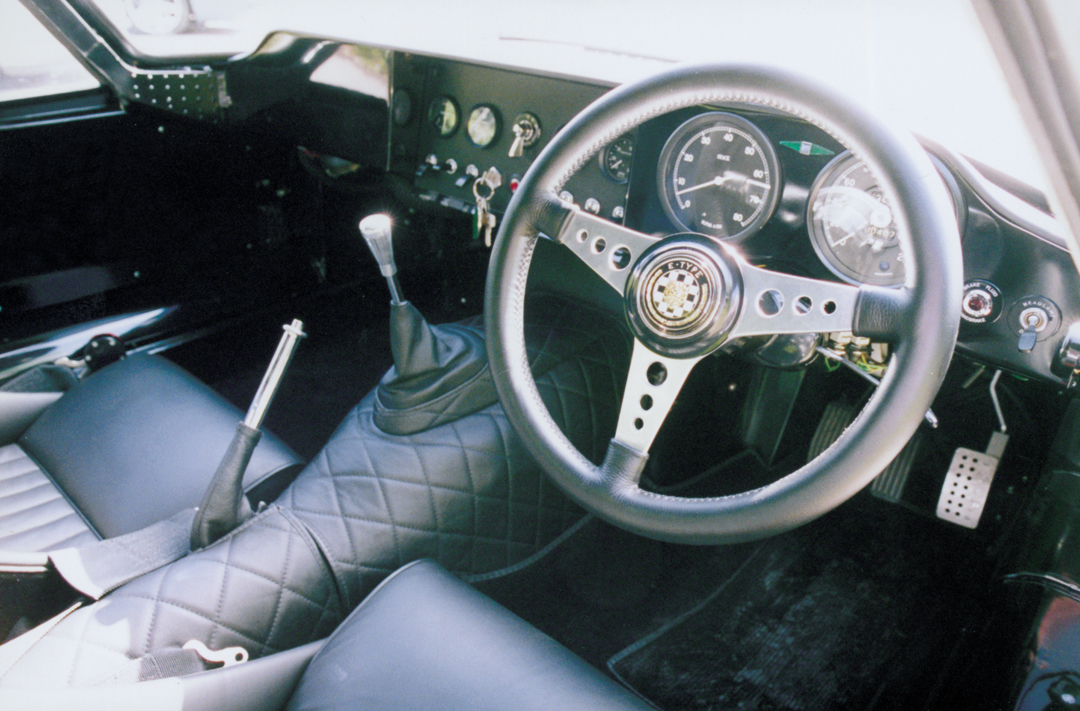

The photos showed how the original Lindner/Nocker panels are used to draw up the bodyline as it is built to the Low-Drag configuration with new steel monocoque and up-rated chassis frames. The bonnet, doors, boot lid, rear wings and roof are handmade in 16 swg aluminum to the original specifications. An FIA roll cage crowds the area behind the two front seats. It is welded in and provides extra stiffening as well as safety. A striking interior feature which becomes evident on the open road has been built into the roof. A spring-loaded roof vent pops open at 56 mph to allow fresh air into the cockpit…this takes the new driver by surprise at first and is a clear reminder of what this car is meant to be!

Driving the Low-Drag Coupe

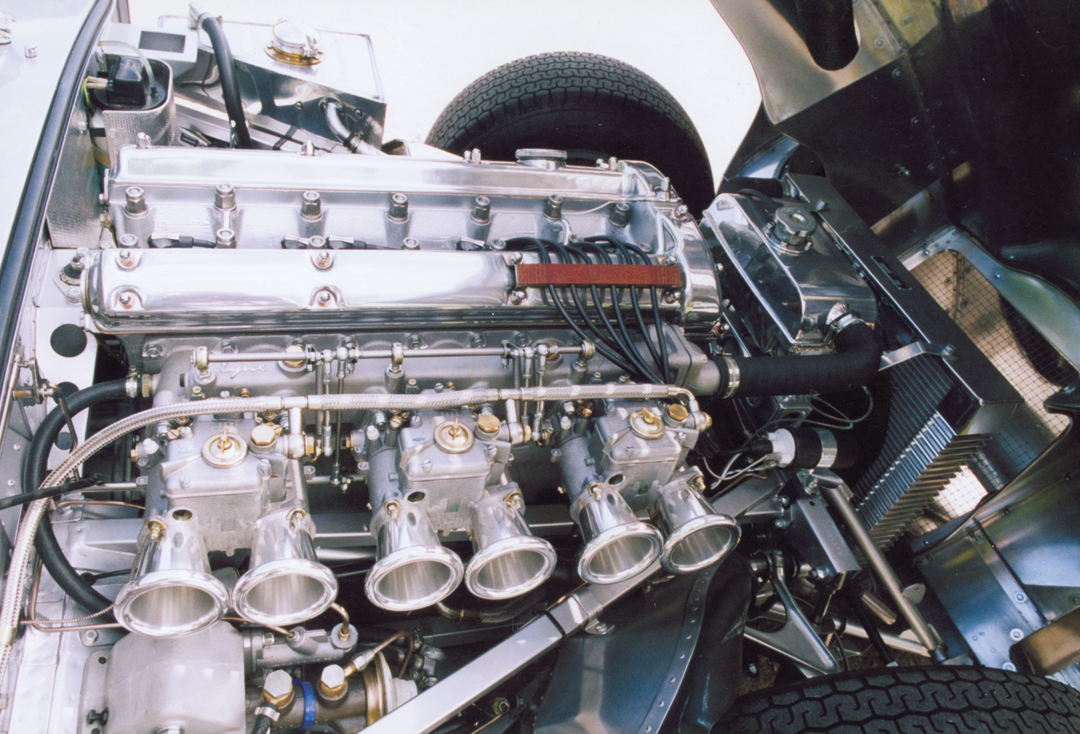

Rapidly changing seaside weather conditions meant we spent virtually a whole day waiting for a reasonable, dry period on the road. This also meant I was getting impatient to get inside this “cat on steroids” and get going, but the wait was worth it. The old cliché about exploding into life may be a well-used one, but it’s hard to think of a better description for what happens when you push the right buttons. The 3.8-liter, cast-iron block with aluminum gas-flowed head really does burst into life and thumps away through that exhaust just below the passenger’s door. With sun now returning to Sussex, we set out to find a mix of open roads to wind up the 320-bhp power unit and some twisty bits to test the handling, with a touch of town driving to see if this was really a car for the road.

The original Lightweight cars started off with four-speed gearboxes and then had five-speed ZF boxes. This car has the Lynx T5 close ratio version with 0.8:1 overdrive top, as well as an up-rated steering rack and Lynx’s own solid rack mounting bushes for a positive steering response. These combine to make it extremely easy in the first few miles to get used to the car before any harder work is done. In fact, I was amazed that a car that could smell, feel and sound like an early ’60s GT car could be so easy to guide through the narrow Sussex villages and linger at the traffic lights in Rye and Hastings with no trouble at all. At one point, the car was on a steep grade waiting for the lights to change and I was trickling uphill in first at 700 rpm, and no smell of burning clutch or steaming radiator. An aluminum radiator to Lightweight E-Type specs is responsible for that. It truly is a user-friendly road car.

But the good moments were to come, out on a quiet country road with some nice decreasing radius bends with a bit of camber. The bark of the exhaust gets more urgent as the revs rise, pushing hard up through the gears and then down again. Where the road was smooth, the car could be pushed hard into corners, but where there were bumps the stiff springs brought the rattles to the fore and the car moved about as you would expect. It was very period but a bit distracting, though the knowledge that the Lynx suspension is eminently adjustable and can be dialled in for the conditions made this not a nuisance but a characteristic of a real period machine. Thus it was interesting technically as well as great fun to drive.

The dash features the 200-mph speedometer of the original cars, but I have to say we made no attempt to see how close we could get. As the car is set up, perhaps 160 is not out of the question, but 100 mph down a long Sussex road was certainly enough to see the racecar side of its personality. Braking was so good that some quick runs were easy to achieve. The car has modern XJS brakes with modified XJ6 discs at the front, brand new from a Jaguar dealer, designed to stop a two-ton car, so as Mayston-Taylor says “they’ll never wear out.” They are much easier to live with than the thought of rebuilding original E-Type brakes and they are so efficient that vented-discs are unnecessary. These stop a 1,400-kg machine with ease.

An hour behind the wheel found me back in the old days of uninhibited Jaguar driving. The only problem I had was feeling deprived of being able to see what I was flying round the lanes in, though a drift through a town brought pedestrians to a halt in surprise. Disappearing out into the country again brought the noise and exhilaration of a proper racing car, the exotic, frictionless shape cutting through the air, the bonnet-mounted bug-screen leaving a perfect dry rectangular shape on the windscreen…a racing device that really works!

Some nine hours after we had arrived at Lynx, it was time to go, the echo of the car’s exhaust still hanging in the Lynx workshop. We had seen virtually every inch of the facility, been through the customer restorations and thumbed the records in the comprehensive car-build files. Even with all the distractions, though, the eye kept returning to that sexy silver coupe sitting there, exuding history.

Buying and Maintaining a Low-Drag Coupe

I expect that we will be seeing some of these cars on the American scene before very long. Americans love Jags, and always have, and here is a car that not only breathes the past, but can be built to the purchaser’s specifications…you can even have the 340 bhp alloy block if you want it. The car is built with relatively easy maintenance in mind, and if you use it as a track car, which seems quite likely, you will still find it pretty trouble free, and that is a lot different than what happens with much period machinery. The three-carb set-up is potent but manageable, but you can go for injection if you like. The cost, of course, depends on the specs chosen. The car we tested is available for about $225,000, but that is a guide price only and the price for a new one depends on just how far you want to go in creating your own private heaven.

Specifications

Body: Monocoque with aluminum body

Wheelbase: 8 ft

Steering: Rack and pinion, up-rated steering rack, solid rack mounting bushes

Front suspension: Lynx eccentric top wishbone spindles, up-rated torsion bars, adjustable dampers with bump stops

Rear suspension: Bottom wishbone and drive shafts modified, positive location rear suspension cradle, up-rated springs, adjustable dampers

Engine: 3.8-liter cast iron block

Cylinder head: Aluminum gas-flowed and blue-printed with enlarged ports

Power: 320 bhp at 5,800 rpm

Carburetion: 3 Weber 45 DCOE carbs with solid billet ram-pipes

Gearbox: Close ratio five-speed Lynx T5 with 0.8:1 top

Brakes: Front and rear: multi-pot calipers on large discs

Wheels: Cast magnesium alloy Dunlop peg drive, 6inch rim front, 7.5inch rear, with Dunlop Racing 600M-15 front tires, 650M-15 rear

Resources

Porter, P. Jaguar: Sports Racing Cars, Bay View Books, U.K. 1995.

Thanks to John Mayston-Taylor and the Lynx team for their help and many hours of their time. www.lynxmotors.co.uk