Maserati Birdcage

Tipo 60 / 61 / 63 / 64 / 65

Produced between the years of 1959 and 1961, Maserati Birdcage had five different models, all based on an intricate multi-tubular frame concept with perfect aerodynamics and a 50/50 front-to-back weight distribution. All of them were made for racing events, including the famous 24 Hours of Le Mans. The Maserati Tipo 60 and 61 broke ground and records alike with their debut. But the innovation didn't stop at the 60/61. The saga continued with the audacious Tipo 63, followed by the even more daring Tipo 64, each iteration pushing the boundaries of technology and design further. And just when you thought the pinnacle had been reached, in roars the Tipo 65.

Overview / Featured / Models In-Depth / Image Gallery / More Updates

The Ultimate Guide & History

In the late fifties, income from Maserati’s successful 3500GT meant they could again develop racing cars like the Maserati Tipo 61. Design engineer, Giulio Alfieri drafted an intricate chassis design that was nicknamed the Birdcage. After only six cars, the complex design was upgraded to have a larger engine for American racing. In this Tipo 61 configuration it won many victories including the Nürburgring 1000km.

Initially, the Maserati Tipo 60/61 was received with much criticism. Omer Orsi, the director of the Maserati, had many doubts about the car’s unusual frame. Indeed the Tipo 60 really contrasted with idea of a classic Italian sports car, but it was a product of rapid transformation that started a new philosophy of race car engineering.

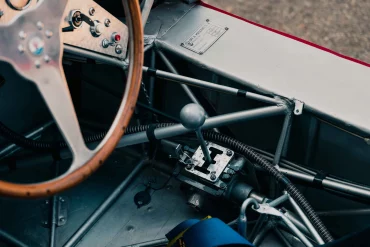

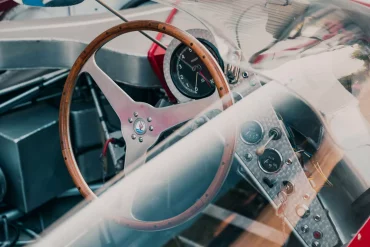

Opting out of using a tub chassis, or ladder-frame chassis, Alfieri’s birdcage instead use small segmented tubes. Over 200 individual pieces were used in the design, having steel tubes with diameters ranging from 10 to 15 mm. The resulting chassis looked like a complex network, almost always described as a Birdcage.

Two challenges arose from the Birdcage frame. These included maintaining a high level of welding throughout the design which had hundreds of connection points and calculating the required elasticity as not to break the welds during stress. Remarkably, the chassis only weighed 80 lbs (36 kgs).

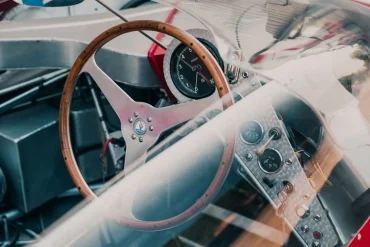

Suspension in the car, both front and rear, was similar to the successful 250F Grand Prix car. It had triangular arms with a coil-over-shock arrangement in the front and a de Dion Tube Axle in the rear. Other components included a rack and pinion steering box and specially built Girling disc brakes.

The engine was placed well back in the chassis and was canted at 45 degrees. This mounting reduced the height of the body and offered a low center of gravity. It was connected to a an entirely new gearbox which was rear mounted and built as one unit with the differential.

The most simple part of the Birdcage was probably the engine itself . It was an inline-4 which was an evolution of the type used in the 200S. The cylinder head was modified extensively to include actuation of the valves by rockers. Lubrication in the engine was by dry sump which included an unusual triangular oil sump.

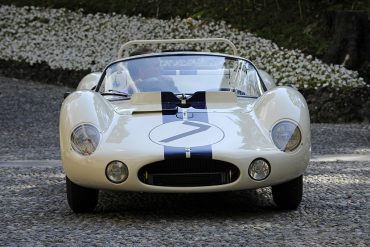

The exterior lines of the car were a direct result of the Tipo 60 chassis concept. The car featured a very small frontal area leading to a low engine cover that completely flips forward for easy access. Gentilini and Allegretti, both former employees of Maserati, were responsible to the body’s design. They opted to hide the rear roll bar by covering it with a rather large headrest.

A pressing request came from the United States which saw the potential and superiority of the Tipo 60’s chassis. Specifically, many Americans wanted a three liter version to compete in SCCA events. Such a car would also be eligible to enter the World Sports Car in the under three liter class which was Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa territory. Due to the size of the engine block, the maximum geometric size available was 2.9 liters. Fortunately, this was enough to move ahead with the project and the Tipo 61 was born.

The design of Tipo 61 chassis remained the close to preceding model’s design. The braking system was enlarged to 14 inches with improved caliper mountings. A heavier crankshaft and connecting rods, along with the brakes, contributed to the 30kg that made the Tipo 61 a heavier car. Because of this weight, the Tipo 61 actually had a worse power to weight ratio than the Tipo 60.

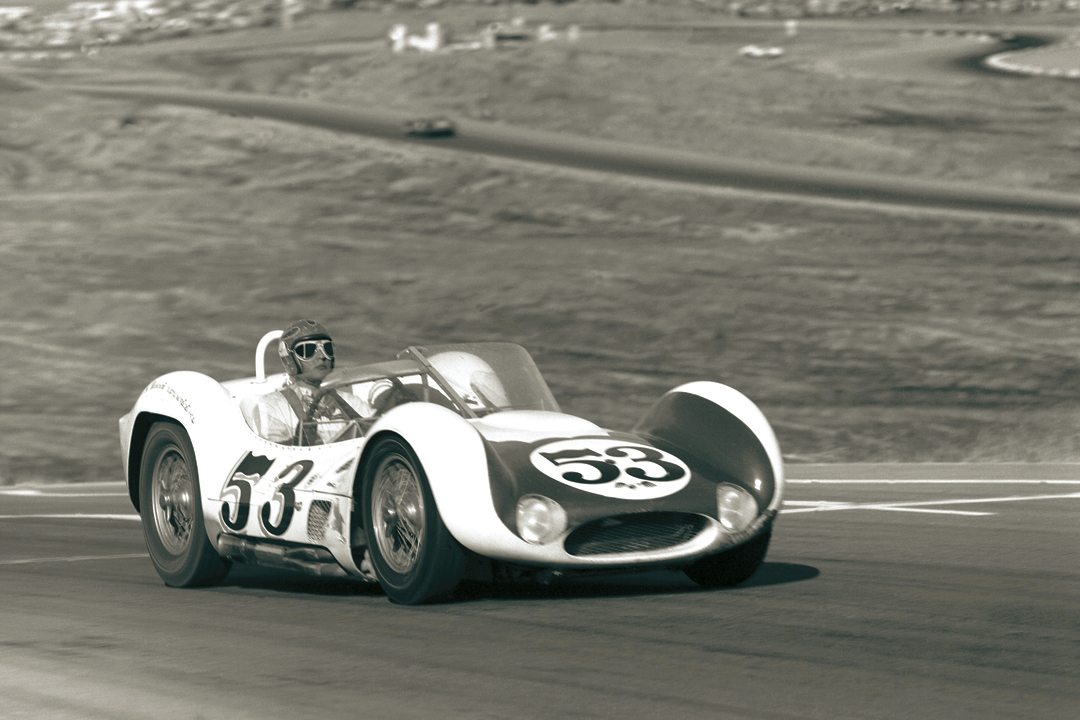

The Maserati Birdcage debuted in the hands of Stirling Moss who used the car’s light fuel consumption and extremely low weight to win the 1959 Delamare-Deboutteville Cup, a support race for the Rouen GP. Tipo 60 cars went on that year to take many hillclimb and gentlemen-drivers victories.

After the debut of the three liter car, the Tipo 61 really made its mark in America. Gus Audrey took the SCCA class championship in his Tipo 61, with Roger Penske doing the same in 1961. These victories made the car very popular in America which motivated some teams to try the car in International Motor Sport.

Since Maserati’s new management forced the elimination of officially sanctioned motor sport activities, the Tipo 60 and 61 were sold to private racing teams. Among them, the Casner Motor Racing Division (Camoradi), founded by Lloyd Casner, would be the most important. He negotiated a deal to take delivery of new Tipo 61s to run in the CSI’s 1960 World Sports Car Championship.

Unfortunately, the Camoradi team saw more retirements than finishes during the 1960 season. The Birdcage almost always set the lead pace for most of the rounds, but reliability issues plagued the effort. The Constructor’s Championship went to Ferrari that year with their Testa Rossas. The highlight of the Camoradi season came when Stirling Moss and Dan Gurney won the Nurburgring in chassis 2461, despite bad weather and heavy competition from Porsche’s 718 RS60, Ferrari’s 250 TR59/60 and Aston Martin’s DBR1. Moss described it as “my toughest victory ever in sports car racing.” He had been soaked in oil at the begining at at the end multiple chassis tubed had broken.⁴

For 1961, many manufacturers followed Porsche’s lead and entered rear engined cars in the championship. While these cars were very much in the prototype stages, they showed much promise. Maserati debuted their rear engine Tipo 63 car at Sebring, to take second in class. During the next race, at Targa Florio, Ferrari’s rear engine 246SP took the overall victory in just its second race.

Again, the Nurburgring would highlight the Camoradi and Tipo 61’s season. Almost unexpectedly, Masten Gregory and Lloyd Casner drove # 2472 to the overall victory. This once again proved how capable the Tipo was, and, if it had been more reliable, the 1961 Constructor’s Championship could have been given to Maserati, remarkably in the hands of private entrants.

The Tipo 63 took Maserati’s sports racecar from Birdcage to Supercage. That is, from a front-engine, four-banger into a screaming sports racer with a V12 behind the driver. This transition took place over the 1961 season with rapid development that often changed specification from race to race. This hastiness led to some mechanical failure, but a few outstanding victories were scored.

Like every manufacturer making the leap from front to mid engine, Maserati’s engineers found great difficulty in balancing the weight distribution. Furthermore, issues of making room for rear transaxles and maintaining reliability were even more difficult. These factors made the Tipo 63 somewhat less successful than the old Tipo 61 Birdcage it replaced.

Maserati began testing the new mid-engine Tipo 63 Muletto in December of 1960. This car wasn’t entirely new. Instead it was an economical transformation of the front-engine Tipo 61. Both designed by Giulio Alfieri, they used the same principle for their chassis including a complex network of thin tubes to support the running gear and aluminum body. Due to a limited budget, the Tipo 63 also used many of the Birdcage’s components including a similar transmission and the four cylinder engine instead of a preferred V8.² This engine cylinder was canted an angle of 58 degrees in the chassis to accommodate downdraft 48 IDM Webers instead of smaller side-draft versions. This helped produce 15 more horsepower, reaching 265 bhp.

To fit the new transaxles, Tipo 63 chassis were all new at the rear. The bulky de Dion suspension was replaced by double wishbones and half shafts to help with weight distribution. Furthermore, twin 60 liter fuel tanks were relocated into the side sills.

Initial tests of the bare-aluminum Muletto prototype were unfavorable and it was criticized for being too short. Fortunately, Maserati persisted and begin production of the first three Tipo 63s to stay competitive with the other mid-engine sports cars like the Ferrari 246SP, Lotus 19 and Cooper Monaco.

In an effort to keep make the Tipo 63 competitive, Maserati was constantly making radical changes throughout the season to make it faster than the older Tipo 61. Remarkably, the initial chassis and engine configurations in 1961 were unsuccessful, so much so they were scrapped for parts later in the season. This was probably due to the reliance on an old engine design and a complex chassis that was overly flexible.

Alongside a few of the front-engine Tipo 61s which were still very competitive, three teams contested the Tipo 63 Maserati in 1961. These three were Count Volpi’s Scuderia Serenissima, Lucky Casner’s Camoradi team and Briggs Cunningham. Each spent considerable time developing the cars for the European World Sports Car Championship (WSCC) which opened at the 12 Hours of Sebring.

The Tipo 63’s race debut at Sebring ended with rear suspension and transaxle failure for both cars. Immediately the new Tipo 63 proved to be too complex and unforgiving. As an example, to comply with minimum windscreen regulations Maserati fitted a long, nearly horizontal, Plexiglas front windscreen which was tough to see out of or over. Furthermore, flex in the chassis combined with a heavily-vibrating engine caused too many problems. Most drivers, including Stirling Moss, immediately preferred the more balanced Tipo 61. Maserati needed change.

At the second WSCC round at the Targa Florio, Maserati debuted two new cars for Scuderia Serenissima, one lacking the usual roll-bar. Both featured longer, more protruding noses and Dunlop disc wheels. One of these was specially built with a 50mm longer wheel base (LWB) to help with handling and it proved to be much faster. Both cars showed uncharacteristic reliability and finished fourth and fifth overall.

Nurburgring 1000km was a surprising success for Camoradi’s Maserati, but only for the old Tipo 61 driven by team boss Lucky Casner and Masten Gregory. Two Tipo 63s had their long-sloping Plexiglas windscreens replaced by glass counterparts from the Alfa Romeo Sprint Speciale. One retired with a transaxle crack while the other finished 23rd overall.

The sole LWB birdcage from Targa Florio was actually a segueway to introduce a V12 engine that would need the additional space. Extra horsepower was greatly needed for the faster tracks like Sebring and Le Mans. Furthermore, the smoother V12 didn’t rattle the rear end to oblivion like the four bangers. In this configuration, Maserati was the first to install a mid-ship V12 in a sports car, beating Ferrari’s 250P by two years.

Maserati used a version of the V12 that was developed for the 1957 250F T2 in Formula 1.² To endure the torture of a long distance race, drivers kept to 8500 rpm even though 10,000 rpm was used in F1. For Le Mans, all three cars were equipped with a V12, but each with a slightly different bore and stroke that varied output from 310 to 320 bhp. Only Cunningham received a LWB V12, while the other two cars were converted from old SWB chassis and suffered from cramped cockpits. All three had a new and characteristic quad megaphone exhaust protruding out from the rear engine deck. Unfortunately the new V12 had a terrible front to weight distribution of as/12.

In practice, Cunningham’s new LWB Tipo 63 was only one second off pace with top running Ferrari. The new engine raised top speed from 162 mph (260 kph) to 193 mph (312 kph). Unfortunately, the Cunningham car crashed during the race in fourth place after leaking oil over its windscreen. Fortunately, one of the SWB cars managed to finish the race in fourth overall, but only after three lengthy spark plug replacements, needing 24 new plugs that were obscured by small engine openings and burning hot exhaust pipes.

After Ferrari clinched the Manufacturer’s Championship at Le Mans, Maserati went back to drawing board yet again. They changed the rear engine deck to a one-piece design that could pivot from the rear. Furthermore, the exhausts were relocated underneath the body and larger front radiators were fitted requiring front air scoops. The third and final LWB Tipo 63 initially was built in this ultimate specification.

Having only achieved one fourth place in the WSCC, two Tipo 63s were shipped to America to compete in SCCA and USAC races by Cunningham. The results were much more favorable than in Europe: Walt Hansgen won both Bridgehampton and the Road America 500 driving Tipo 63s. When combined with his Birdcage victories, he missed the SCCA Driver’s Championship by just two points. Later in the year, the west coast USAC races had considerably more competition, but the Cunningham team retired six engines in just three races.

At the end of the season a total of seven Tipo 63 chassis were constructed. The Muletto, three SWB cars (two were upgraded with V12s for Le Mans) and three LWB cars were made (two with V12s). Throughout 1961 some chassis numbers were swapped and old chassis scrapped to avoid taxes.

Although the Tipo 63 almost always held a top position before retiring, the fact that it won at all is remarkable. 1961 was very much a development year for Maserati and had they entered more cars with more testing, more victories could have been won.

For the 1962 season it was apparent Maserati needed something new to stay competitive in the US and Europe. The Tipo 64 was drafted up as a much smaller car with revised de Dion suspension and further upgrades.

Our feature car, chassis 63.010 was the most successful Tipo 63, having won two SCCA races for Briggs Cunningham. It was sold in 1965 as an engineless car and was fitted with a Ford V8 engine. Later, it was bought by Peter Kaus and fitted with an incorrect 2.4-liter four-cylinder Maserati engine from a power boat for his Rosso Bianco collection.

After a lackluster season spent developing a rear-engine sports car, Maserati pursued the design for another season with the Tipo 64 in 1962.

In theory, the new car was much like its processor, the Tipo 63. Both shared the same ‘birdcage’ principle for their chassis including a complex network of thin tubes to support the running gear and aluminum body. However, the Tipo 64 was much different in detail. The car was lighter, smaller and lower, mimicking the size of its direct competition, the Lotus 19.¹

For the Tipo 64, engineer Alifieri drafted an entirely new chassis that used much smaller diameter tubing than before. Furthermore the front and rear suspension were reconsidered. At the rear, a flexible de Dion suspension was installed and used a box shaped superstructure instead of a regular tube. This is probably is probably why journalists of the era called it the ‘Supercage’.

Weighing 95kg less that the outgoing Tipo 63, the Tipo 64 was on the right track. Furthermore the driver was pushed forward in the chassis which mended the terrible balance of the earlier cars.

Behind the driver sat an evolution of the V12 engine that was developed for the 1957 250F T2 in Formula 1. To endure the torture of a long distance race, drivers kept to 8500 rpm even though 10,000 rpm was used in F1. With a number of bore-stroke combinations available, the cars fluxuated in specification.

Two chassis were made for the 1962, the first prototype went to Lucky Casner’s Camoradi team while the second was sent to Count Volpi’s Scuderia Serenissima. The later of these had a special body styled by Franco Scaglione that featured a characteristic pointed nose.

Both Tipo 64s debuted at the Sebring 12 Hours in Florida. Unfortunately, both of these retired and set the standard for the rest of the season. Afterwards, Camoradi decided to restrict his car to US racing, while Count Volpi prepared his for the upcoming Targa Florio. Unfortunately, Volpi’s car failed to finish the Targa and he abandoned Maserati altogether.

For LeMans, engineer Alfieri abandoned his rear-engine concept. Instead he used a simple tube-frame chassis similar to the old 450S and fitted a powerful V8 engine in the front. Clothed in a dramatic coupe body, these Tipo 151s look promising but both retired. Alfieri was right, the overall winner was a front-engine Ferrari, but it was the last time a front-engine car would win Le Mans.

Cunningham continued with the Tipo 64 in various SCCA and Westcoast races but it almost always failed in retirement. This car ran alongside the Tipo 151s which must have made Maserati’s effort seem disorganized in 1962.

As a direct successor to the Tipo 64, a sole Tipo 65 was built in haste for 1963.

After Maserati had almost given up on their Tipo 63 and Tipo 64 rear-engine prototypes, they gave the idea one last attempt for Le Mans in 1965. In less than 30 days the engineers at Maserati completed this special prototype at the request of Maserati France.

The project arose when Maserati France needed a car after Lucky Casner fatally crashed their only Tipo 151/4 at the Le Mans practice. With no cars available, Maserati designers Ing. Alfieri and Guiseppe Pelacani revisited the Birdcage program and resurrected a chassis that had been scrapped almost three years earlier.

In theory, the new car was much like its processor, the Tipo 63. Both shared the same ‘birdcage’ principle for their chassis including a complex network of thin tubes to support the running gear and aluminum body. However, the Tipo 65 was wider and heavier to support the Tipo 151/4’s spare V8 engine and wider tires.

The chassis itself was modified from a Tipo 63, probably chassis 63.008 which was in Maserati’s scrap heap. The chassis was split in two pieces: behind the cockpit, the design was entirely new to support the 5044cc V8 and torsion bar rear suspension. A pivoting rear hood was fabricated that gave the car considerable bulk. Overall the car was 420 kg heavier than the original Tipo 63.

With an unknown potential Maserati France showed up to Le Mans with their hastily made spyder. Team manager and owner John Simone organized drivers Joe Siffert and Jochen Neerpasch to drive the Tipo 65. It was up against the best that Ford and Ferrari had brought to the circuit.

Before the race, the drivers attained a lap time of 4’03”00 while the Tipo 151 from one year earlier was capable of 3’59”2. Despite a quite getwaway, Siffert hit the haybails ten minutes into the race and retired the car.

After LeMans the car was repaired, but didn’t leave the factory until 1967. This was partly due to Tipo 65’s weight and the new 750 kg formulae introduced for the 1966 Le Mans. With a new nose, rear coil-spring suspension the car was purchased for use in the European CanAm series, however that never materialized. Instead the car was sent to Modena, where it was modified in Piere Drogo’s workshop to include twin front headlights, a new dashboard and new air scoops. It was raced briefly in the seventies like this until it found a home at the Rosso Bianco Museum in Germany.

Maserati Type 60/61 Basics

Manufacturer: Maserati

Also called: Birdcage

Production: 1959–1961

Produced: 16 + 1 units (Tipo 61), 6 units (Tipo 60)

Assembly: Italy: Modena

Designer: Giulio Alfieri

Body style: 2-door speedster

Layout: Front-engine, RWD

Engine: 1,990 cc (2.0 L) inline-four (Tipo 60), 2,890.3 cc (2.9 L) inline-four (Tipo 61)

Transmission: 5-speed manual

Wheelbase: 2,200 mm (87 in)

Curb weight: 570 kg (1,260 lb) (Tipo 60), 600 kg (1,300 lb) (Tipo 61)

Successor: Maserati Tipo 151

Did You Know?

Its name comes from the intricate "birdcage" of over 200 chrome-molybdenum steel tubes forming its chassis. This design was incredibly strong yet surprisingly lightweight.

Despite its small size, the Birdcage's low profile and slippery body could hit top speeds of 180mph depending on the engine used.

“Great balance, the car is perfectly sprung and the brakes are just right for its power and weight. The adhesion to the track is just fabulous”.

Dan Gurney

“A fabulous car – light, very agile, with fantastic brakes, super easy for steering, enormous torque, and good power”.

Stirling Moss