During the fifties, everyone’s hero was Juan Manuel Fangio. He won the World Driving Championship five times, an achievement that would not be equaled for almost 50 years. The race that put the fifth crown on his head was at the world’s most challenging circuit, the old Nürburgring. At the wheel of an outdated and underpowered Maserati, he beat the best there was at the time.

My wife, Alicia, remembers Fangio from when she was a small girl. Early in his career, Fangio, an Argentinean, competed in South American open road races. The longest and most difficult started at Buenos Aires—at sea level on the Atlantic coast—climbed over the Andes through a 14,000-foot pass, down to Chile on the Pacific coast, north through the Atacama Desert and finished at Lima, capitol of Peru. Alicia was born in and grew up in Lima. She remembers seeing Fangio during the wild celebrations that took place as the cars crossed the finish line.

During 1958, I had a yearlong assignment shooting film in South America. I wanted to visit the 14,000-foot pass, so I rented the least-expensive car available—a Fiat 500—and set off from Santiago, Chile. The Fiat and I climbed and climbed and climbed. Finally, we came to a hill that the little car wouldn’t climb. I turned it around and tried to back up, but it was a no go. I had to return it and rent a more powerful car. I understand that the Atacama Desert is one of the world’s hottest and most desolate places. The Nürburgring must have seemed like a cruise in the park by comparison!

While I was in Buenos Aires that year, I made it a point to visit Fangio and try to get to know him a little. He was most gracious and friendly. If anyone deserved an ego, it was Fangio, but he didn’t exhibit a trace. Due to his winning the championship for Daimler-Benz in 1954 and 1955, he had been granted a distributorship and had a showroom in Buenos Aires. His second-story office had a window that overlooked the sales floor. Frequently, he would come down and help sell cars. From what I could gather, he was a great salesman and always dressed conservatively in a suit and tie.

One day he offered to show me the autodromo, the racetrack at Buenos Aires. We started out in a small sedan, Fangio at the wheel, me riding shotgun. As we drove through the city streets, some pedestrians saw who was in the car. A few, running behind, waved their hands in the air and shouted, “Maestro, maestro!” Ten years after he had retired, he was still their national hero.

Photo: Art Evans

When we got to the autodromo gate, the guard waved us through with a huge smile and a few “maestros.” The autodromo was in a park-like setting, but it was flat as a pancake. We started to do a lap. Fangio, in his suit and tie, with his left arm out the window, was smoking while all the time talking about the circuit.

The last turn before the pit straight was a flat “U.” The road surface was tarmac and the inside of the curve was bounded by a cement curb. Weeds were growing between the tarmac and the cement. As this was a right-hand turn, I could look out my window and see the apex. Driving with one hand, Fangio didn’t seem to be paying any attention to the road. But I could see that the car was in a full four-wheel drift with the right-front tire clipping the weeds.

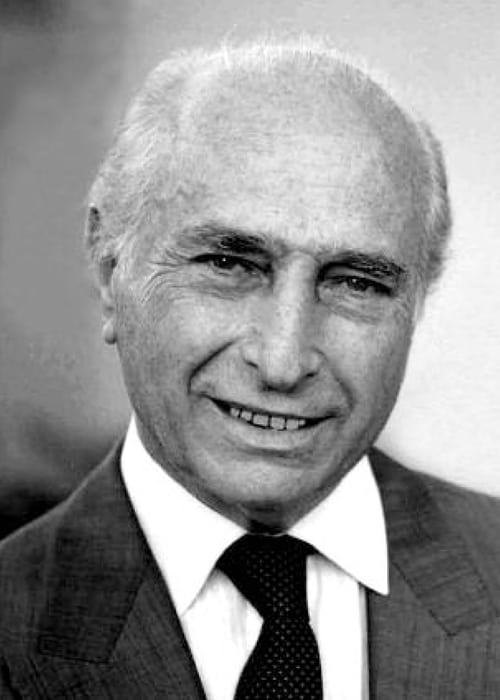

For all the years after my visit and until his death, we exchanged Christmas cards. Alicia has kept every one and treasures them. The last time I saw Fangio was when he was inducted into the San Diego Automotive Museum Hall of Fame on July 24, 1990. By then, I had started my self-assigned task of taking portraits of fifties-era race legends. Fangio agreed to let me shoot him before the ceremonies started. We went outside, to the front of the museum building, and I brought a chair for him to sit in. Every now and then, while I was shooting, some self-important personage would try to get his attention. He politely shooed them away, telling them (in a language they probably couldn’t fully understand) that we were occupied just then, continuing to give me his full attention. That’s the kind of a guy he was.

Photo: Art Evans

After processing the film, I made a few 11×14-inch prints and, at a gathering a few weeks later, he most graciously autographed them. I sent one to Stirling Moss, who had started me off on my portrait project and another was a present for John Fitch. (Moss and Fitch were Fangio’s 1955 Mercedes teammates.) I kept two, and they are among my most prized possessions.