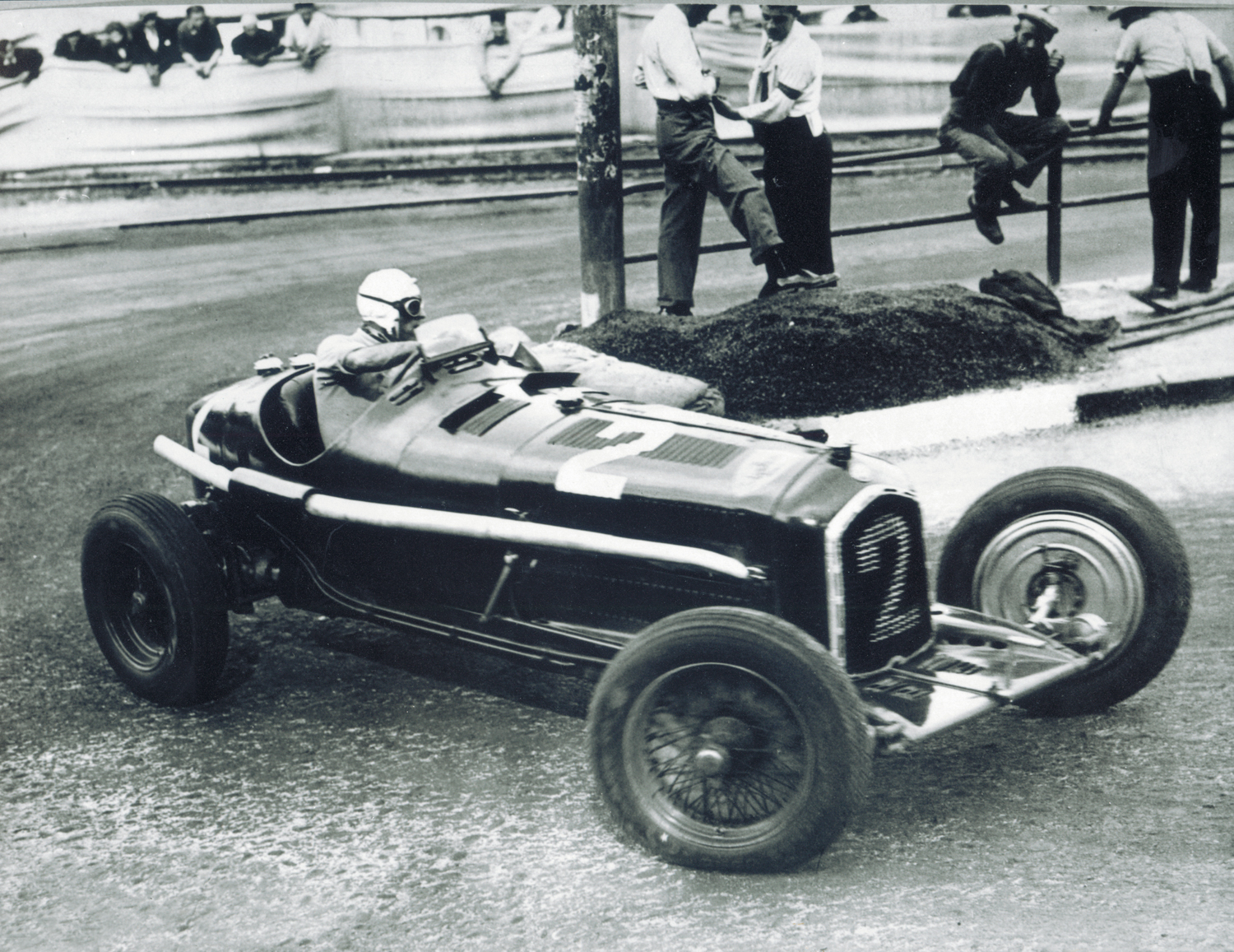

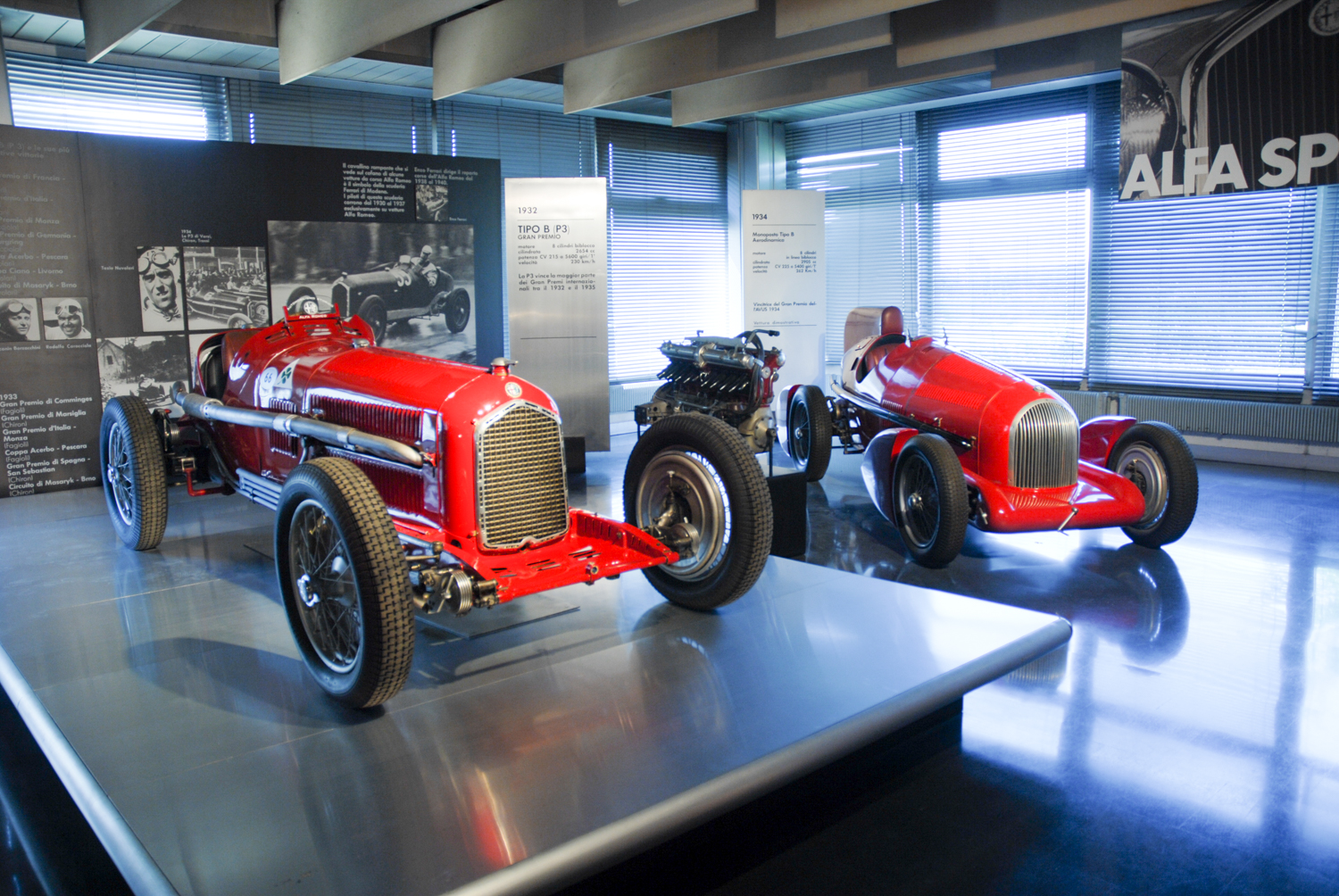

Monoposto! The racing record of the Alfa Romeo Type B is the stuff of legends. The name evokes the images of astounding victories over the mighty German teams of Mercedes and Auto Union and is forever intertwined with the names of Tazio Nuvolari, arguably the greatest Grand Prix driver of all time, Achille Varzi, Louis Chiron, Guy Moll, and Guiseppe Campari.

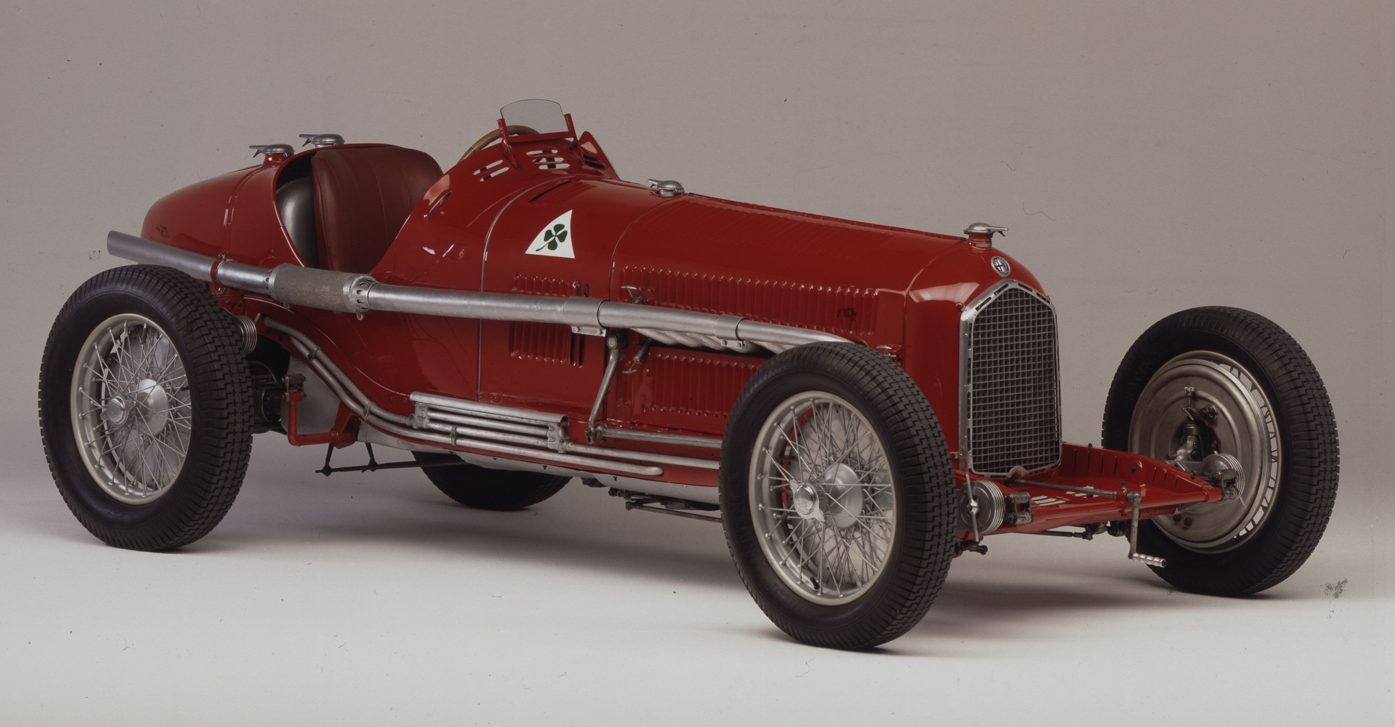

Alfa’s Type B Monoposto was designed by Vittorio Jano in 1932. His design was elegant and functional and marked the high point for the classic school of leaf-sprung racing cars that evolved following WWI. The monsters of the first decade of the 20thCentury were being replaced by much more sophisticated designs at the outbreak of WWI. The progress continued, following the war, with the refinement of the live axle/leaf spring suspension grand prix cars in the 1920’s and early ‘30’s. This refinement continued until the introduction of cars designed with independent suspension, marking the onset of the next stage of racing car design in the closing years of the 1930’s (until peace-time pursuits were interrupted by the outbreak of WWII).

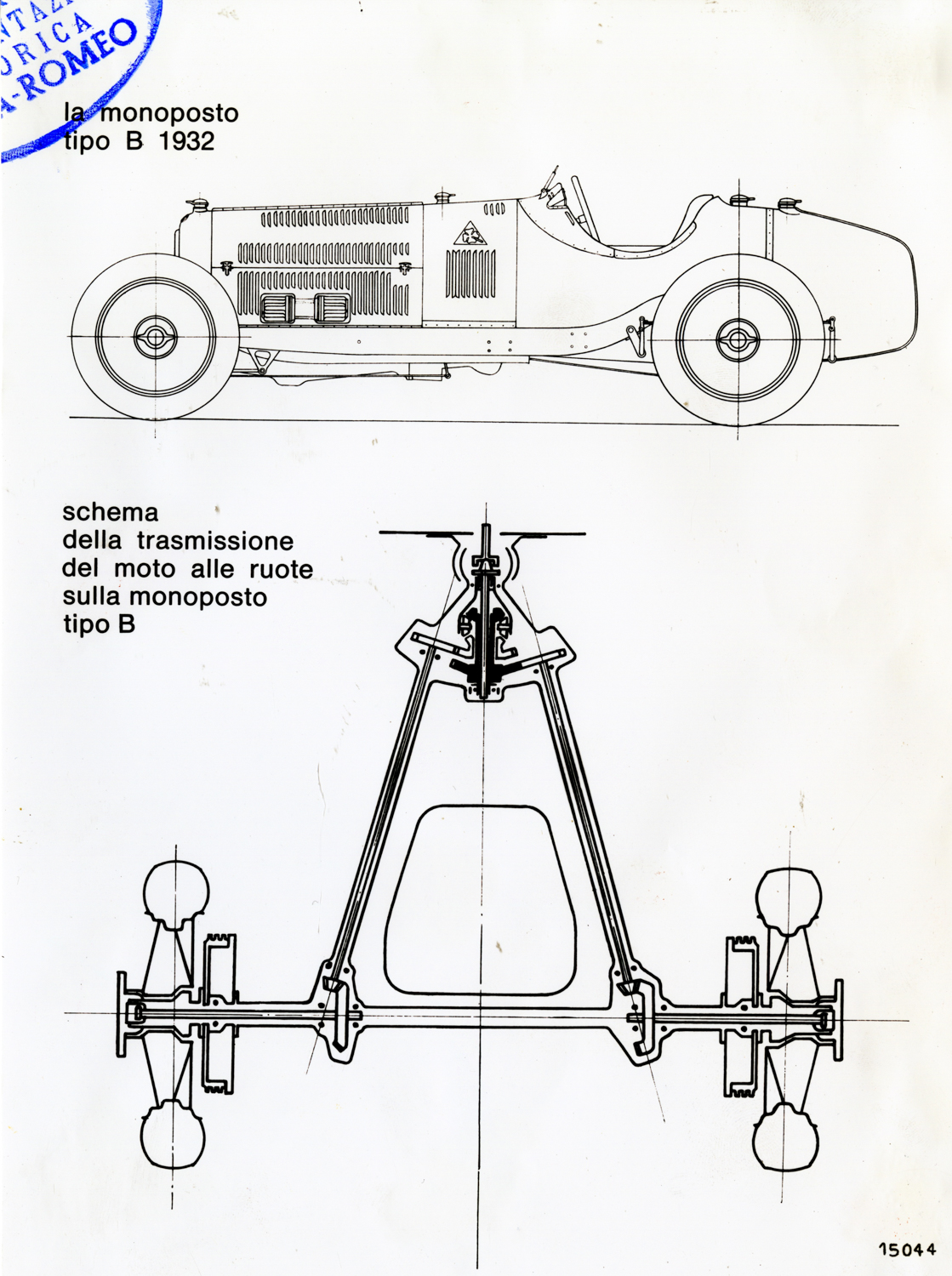

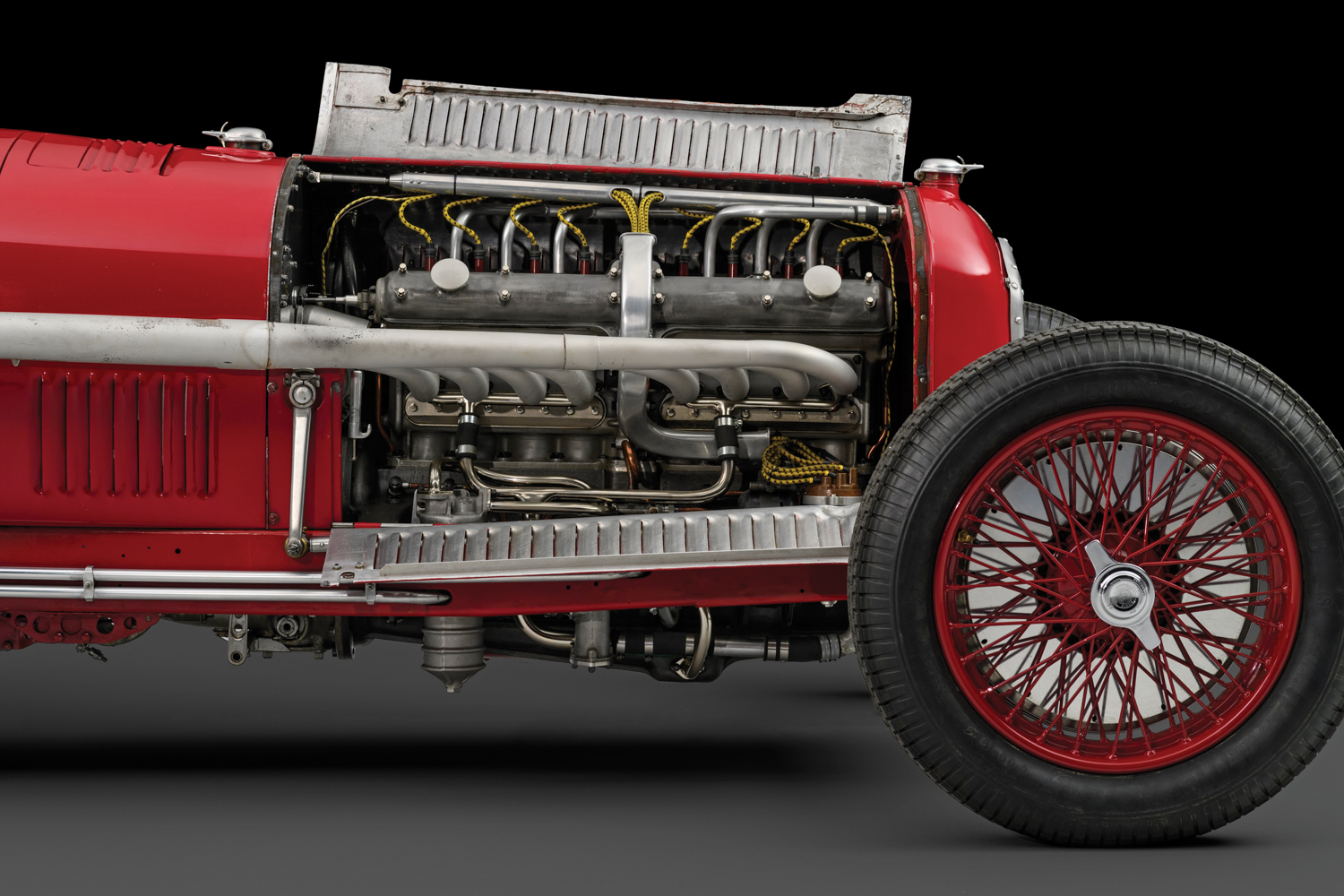

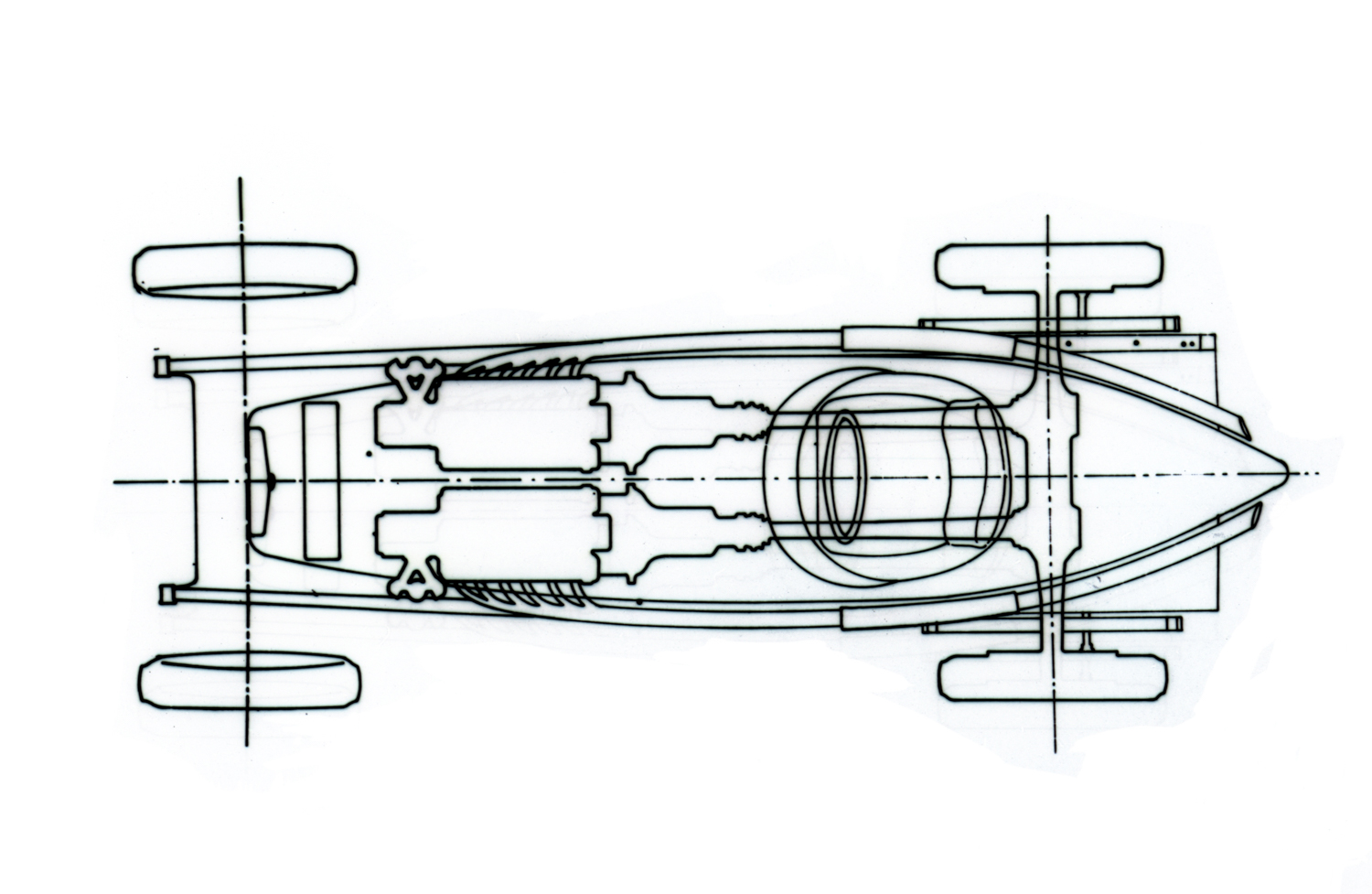

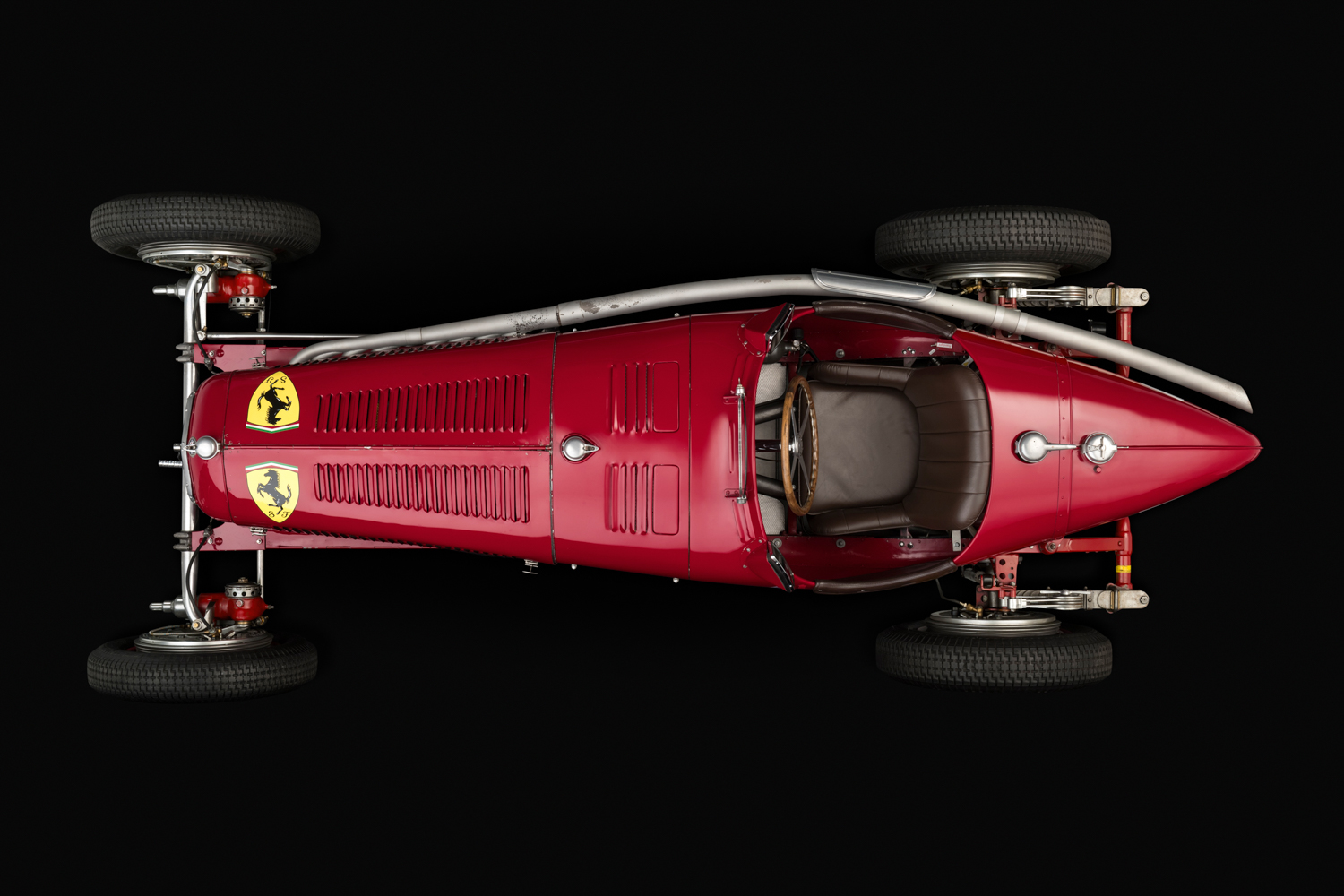

In general layout, the Type B Monoposto was conceptually much like its competitors, fielded by Maserati and Bugatti. It had a straight-eight engine, located behind the front axle and ahead of the driver. Power was delivered through a transmission located behind (and usually attached to) the engine and then by drive shaft to the rear wheels. By the 1930s, this was through a ring-and-pinion and differential gear set located in the center of a live axle. Most modern pick-up trucks have excellent examples of this type of final drive/rear suspension arrangement. The chassis was a straightforward ladder frame, fabricated from channel sections. The front suspension consisted of a conventional beam type axle with leaf springs. Where the Type B differed significantly from its contemporaries was in its final drive and rear suspension.

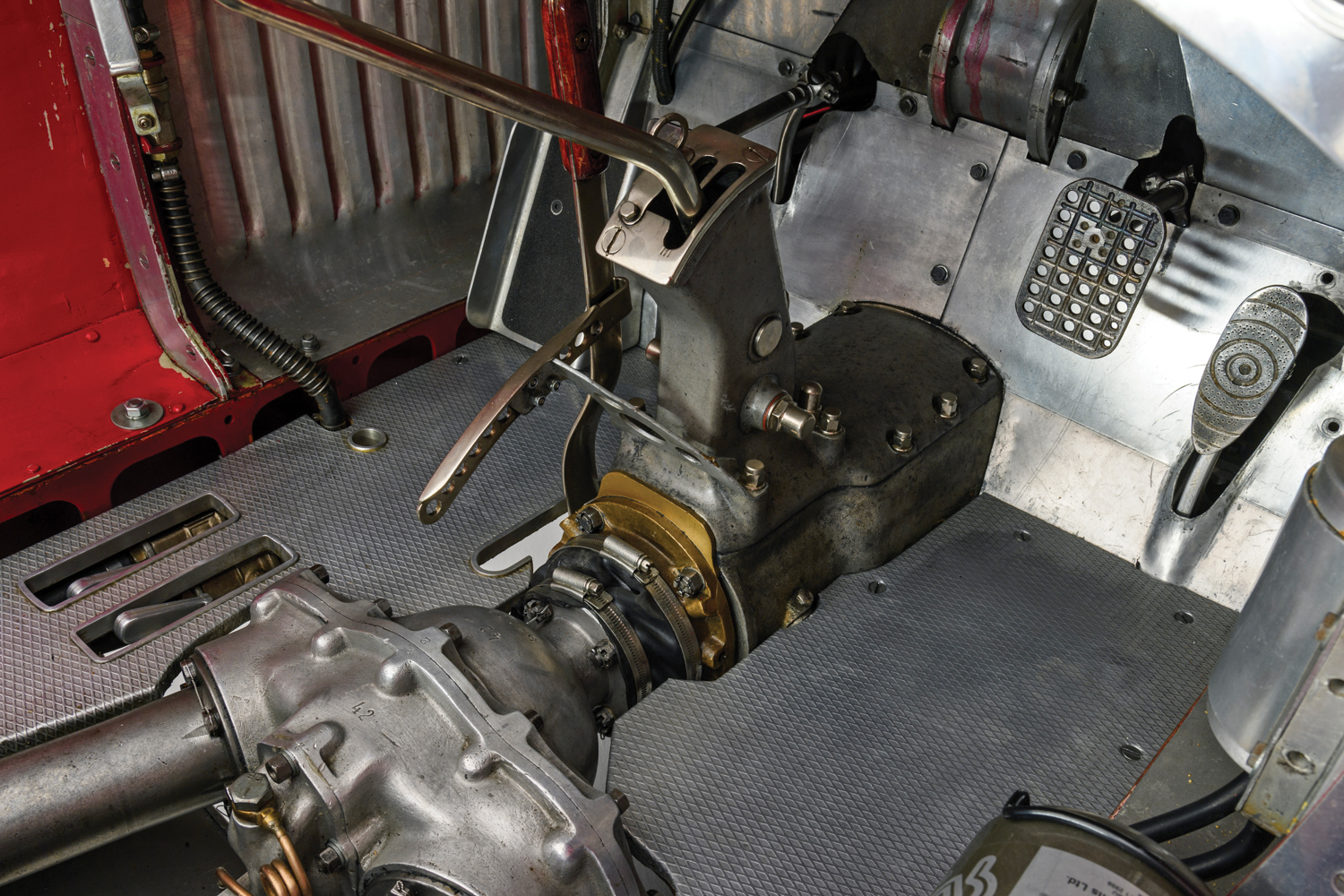

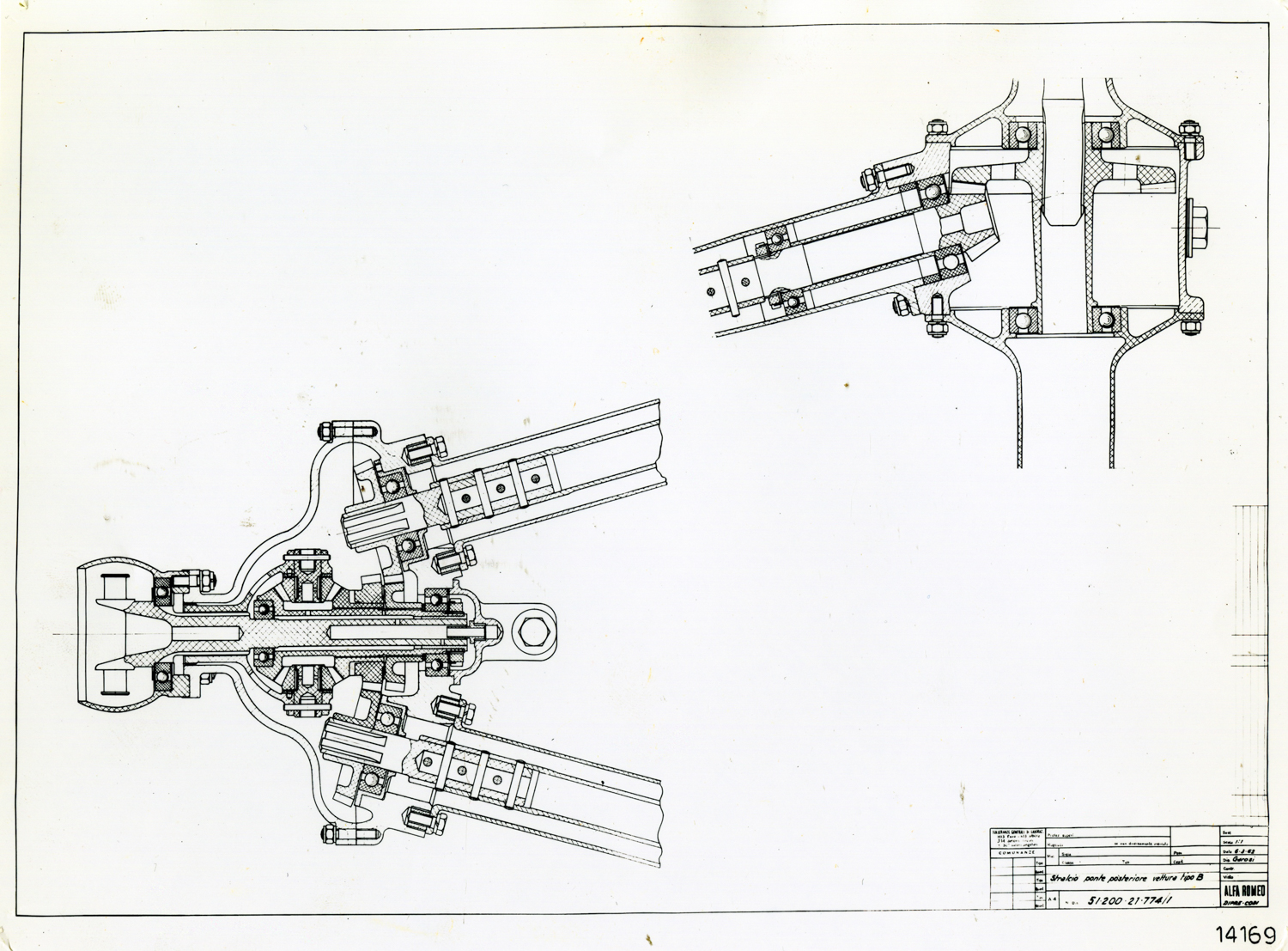

In the Type B, the differential was located at the transmission end of the drive shafts, directly behind the transmission (See Figure 2). A separate drive-shaft delivered power to each rear wheel. The drive-shafts angled outward toward the rear, driving a ring-and-pinion gear set, close to each of the rear wheels. A light tubular axle connected the rear wheels. The drive-shafts passed through tubular enclosures that connected from the differential housing to the ring-and-pinion housings at the rear axle. The differential housing was connected to the rear of the transmission by a large, ball-shaped enclosure that located and supported the forward end of the differential drive-shaft rear-axle assembly. The ring-and-pinion final drives did not have to incorporate the differential, and so could be made much smaller and consequently lighter. Likewise, the size of the ring-and-pinion housings were also smaller and lighter than for a live axle. The rear axle was supported by leaf springs.

The reasons for this complex arrangement have been the subject of much speculation since the cars first appeared. Laurence Pomeroy, a contemporary of Jano’s was unable to explain the reasons for the design in his classic study, “The Grand Prix Car”. Others have speculated about this over the years, including the excellent article in the March/April, 2016, issue of Road and Track. None of Jano’s colleagues or contemporaries have been able to report any analysis from him on why the suspension and final drive were designed as they were. The best report from a contemporary was by Gianbattista Guidotti to Doug Nye (in Thoroughbred and Classic Cars, November, 1982):

“Jano’s idea with the system was to prevent wheel-spin, to maintain traction, always keep both wheels driving adequately, and to make ratio changing to match the car to a new circuit relatively easy, and to drop the driver’s seat low down between the shafts. [Guidotti chuckles one of his mischievous chuckles at my perplexed surprise.] Hah! But when Jano tell (sic) our drivers what he plans, Nuvolari snorts through his nose and says, ‘No! I don’t want to be down in the basement like that. I wanna (sic) be up on top of the job! I want to see where I am going in road racing.’ And the original idea was changed, narrowed and we ended up sitting high on top.”

But, the functional objectives to obtain the benefits Giudotti gives for this design have remained a mystery.

Instead of asking, “Why did Jano employ this complex arrangement for the rear suspension and final drive for the Type B?”, let us re-phrase the question to ask, “What benefits do this rear-axle configuration provide?” After all, the old adage, “Form follows function”, is surely applicable.

First, let us consider the issues inherent in the final drive and rear suspension of the contemporary racing cars. The basic functional requirements for the rear axle and suspension were to support the rear of the car and transmit power to the rear wheels. The rear suspension arrangement must also control the motion of the wheels and axle as power is delivered through them and the vehicle rolls down the road. The conventional live axle rear end, both then and today, looks like a “T” , with the wheels at either end of the cross bar and the drive shaft being the vertical line. The heavy ring-and-pinon and differential gear-set is located at intersection of the “T”.

The property of the engine’s power production that affects the response of the chassis and rear suspension is torque. For those who were not paying attention in science class, torque, caused by a force which acts at a distance from an axis, acts to turn a shaft about its axis. When you turn a nut with a wrench, you apply a force to the free end of the wrench, at a distance from the nut, and produce a twist, or torque, on the nut at the other end of the wrench. When the driver depresses the accelerator pedal, opening the throttle, the engine produces torque.

Most engines turn in a clockwise sense as viewed from the front end of the crankshaft (or counterclockwise as seen from the power delivery end of the engine). For traditional or conventional front-engine – rear-drive cars, this is also the front relative to the car. As the throttle is opened and the engine produces torque in the crankshaft, the engine block tries to rotate in the opposite direction (in accordance with Newton’s Third Law, for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.) This rotation of the engine block is resisted by the chassis, to which the engine is attached. The torque applied to the chassis is, in turn, transmitted through the suspension and wheels to the road. The effect is to twist the chassis toward the passenger side. Given enough flexibility of the chassis and suspension, this can result in lifting of the left (driver’s side) front wheel.

The torque is transmitted by the drive shaft to the rear axle, where, in a conventional live axle, it is transmitted to the axle shaft through a ring-and-pinion and differential gear set, that turns the drive shaft axis of rotation 90-degrees, ultimately causing the wheels to turn. The torque at the rear axle also acts to rotate the entire rear-axle assembly in the same direction as the drive shaft, but this is resisted by the wheel acting on the road.

There are several results from these loads. First, the resulting load on the driver’s side rear wheel is increased and that on the passenger’s side wheel is decreased. Given equal coefficient of friction between the rear wheels and the road surface, for a conventional rear axle with central differential (permitting the wheels to turn at different rates when going around a corner), the unloaded right rear wheel may break loose and spin. Second, because the axle is supported by the road, the twist in the chassis will compress the suspension on the passenger’s side, even though the force between the tire and the road is decreased by the torque applied to the axle by the drive shaft. Third, the torque transmitted by the pinion to the ring gear not only acts to turn the wheel, but as the pinion turns it “tries to climb” around the ring gear. Since the pinion is supported by the axle housing, this action twists the axle housing, so that the front end of the ring-and-pinion housing tries to rotate upward. For a conventional live axle and leaf spring suspension, this lifts the front part of the leaf springs and, in turn, causes the front of the chassis to lift. In doing this, the upward rotation of the axle housing produces an elongated “S” deflection in the leaf spring.

There is a lot of energy stored in the springs under these conditions. If a wheel loses traction, or bounces over an irregularity in the road, this energy will be abruptly released. A cyclic grip-release-grip cycle, with associated wheel hop, can occur under these conditions. Once started, the throttle must be closed, cutting the engine torque, to return the rear suspension to stable, controlled motion. The mass of the ring-and-pinion and differential gears adds difficulty in controlling rear axle motion. In the era of friction shock absorbers, controlling suspension motion was much more difficult than with hydraulic shocks.

Figure 3 shows a modern drag-race car that displays the results of these forces. Under the torque produced by a very powerful engine, the car has twisted and the front end lifted so that the left front wheel is off of the road surface.

These effects were understood by race car designers before the onset of WWI. To address the rear spring deflection caused by the axle housing twist, which tries to raise the front of the car, torque tubes or trailing links were fitted to most cars. A torque tube is a tubular housing which encloses the drive shaft, and is fixed to the axle housing at its rear and pivoted on a pin or ball joint, attached to the transmission case or chassis at its front end. Trailing links are fixed to the axle housing at their rear end and pivot on a pin or ball joint, attached to the chassis, at their front end. An excellent example of the use of a link to control leaf spring deflection and response is the Traction Master ™ link, widely used by drag racers in the 1950’s and ‘60’s, when all cars had leaf springs in the rear. They are still available today and are a cost effective improvement for vehicles with leaf spring rear suspension to control axle response.

These effects were understood by race car designers before the onset of WWI. To address the rear spring deflection caused by the axle housing twist, which tries to raise the front of the car, torque tubes or trailing links were fitted to most cars. A torque tube is a tubular housing which encloses the drive shaft, and is fixed to the axle housing at its rear and pivoted on a pin or ball joint, attached to the transmission case or chassis at its front end. Trailing links are fixed to the axle housing at their rear end and pivot on a pin or ball joint, attached to the chassis, at their front end. An excellent example of the use of a link to control leaf spring deflection and response is the Traction Master ™ link, widely used by drag racers in the 1950’s and ‘60’s, when all cars had leaf springs in the rear. They are still available today and are a cost effective improvement for vehicles with leaf spring rear suspension to control axle response.

Controlling the longitudinal torque effect that twists the chassis relative to the road and tries to lift one rear wheel, was more problematic. Chain-drive cars had been free from this issue because mounting the final drive on the chassis contained the torque reaction within the chassis, rather than at the road. That is, the engine torque did not twist the chassis relative to the rear axle and ground. In addition, with chain drive the rear springs did not carry the reaction to the torque turning the wheels through the ring-and-pinion gears, and the simple beam rear axle connecting the wheel-and-sprocket assemblies was much lighter that a live rear axle. For these reasons, chain-drive cars had much better handling than the cars with live rear axles. As a result, some race cars continued to be built with chain drive after the live axle arrangement became commonplace for road cars. As an example, Ray Haroun’s Mormon Wasp, the 1911 Indianapolis 500 winner, had a live rear axle and leaf springs, but David Brown’s 3rd place Fiat had chain drive. The Fiat Tetzlaff drove to second place the next year also had chain drive.

The Type B final drive and rear axle configuration did not address the torque effect, which twists the chassis relative to the road and tries to lift a rear wheel. A design to contain this torque within the structure of the engine and gearbox assembly would appear with the adoption of independent rear suspension in the Type C, in 1935.

Control of the torque effects was a fundamental functional requirement for racing cars designed at the time that Jano designed the Type B. The Type 35 Bugatti employed quarter elliptic rear springs with links to locate the rear axle to avoid using the springs to resist twisting of the axle housing. The Maserati 26M had conventional leaf springs and employed a torque tube to prevent twisting of the axle. Neither of these made an effort to contain the torque within the chassis structure. In 1931, Alfa fielded the Type A Monoposto, which was fitted with two, 6-cylinder engines. The Type A had a separate transmission, drive shaft and torque tube for each engine. This avoided the problems inherent in gearing two engines together and to a single drive shaft. It also eliminated the need for a differential and resulted in a light rear axle.

Jano’s design for the final drive and rear suspension of the Type B effectively addressed axle twisting that tried to lift the front of the car, and provided improved control of the rear axle by making it lighter. In doing this, he drew on his experience with the Type A. Removing the differential from the rear axle and placing it behind the transmission required separate drive shafts from the differential for each wheel. This necessity is responsible for the distinctive triangular rear axle housing of the Type B. The triangular housing for the axle and drive shafts also served to transmit the wheel torque to the chassis without loading the leaf springs.

So, Jano’s design satisfied the functional requirements for the Type B rear axle better than its contemporaries, addressing axle twist and providing a light, more easily controlled rear axle.

Jano apparently did not share his thinking with his colleagues and contemporaries. But the results were excellent. The success of the design can be seen in the record books and is the stuff of legends.

The principles that were sound when the Type B was designed are still valid today. Those of us who have replaced rear brakes or donuts on an Alfa Romeo Alfetta series chassis have seen up-close its triangular DeDion axle and trailing arm assembly, which employs coil springs and is located laterally by a Watts Linkage. The trailing arms control wheel torque, like the torque tubes of the Type B. The transaxle contains the torque reaction within the chassis structure. This is why the Alfetta series handles so very well.

Did Jano design the Type B rear suspension and final drive with these objectives in mind? He apparently never told anyone what his functional design objectives were. However, the idea that this complex and highly effective design configuration was fortunate, but unintended, stretches belief. One might as well say that Colin Chapman was lucky in the design of the Lotus Type 25 monocoque Formula One car, or Adrian Newey arrived at the design for the current Red Bull Formula One car by chance. In the final analysis, the design achieves the functional requirements we have discussed here and its performance speaks for itself.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to Alfa Romeo Centro Documentazione for their help in providing illustrations for this article. The author is also indebted to:

Laurence Pomeroy, The Grand Prix Car, Motor Racing Publications, Ltd, London, 1954.

Peter Hull and Roy Slater, Alfa Romeo, A History, Transport Bookman Publications, Great Britain 1982.

Luigi Fusi, Alfa Romeo, Tutte Le Vetture Dal 1910, Emmeti Grafica Editrice, Milano, 1978.

Simon Moore, The Magnificent Monopostos, Alfa Romeo Grand Prix Cars, 1923 – 1951, Parkside Publications, Seattle, 2014.

Finally the author would like to thank Dr. David Smith for his insightful review and suggestions for the article.