In an era when Lewis Hamilton and Sebastien Vettel brook no challenge from team mates and examples of ‘win at all costs’ dirty driving by, for example, Ayrton Senna and Michael Schumacher suggest the concept of sporting behavior has arguably disappeared from top line racing. But it wasn’t always like this.

Right from the start in 1950 Formula 1 Grand Prix racing was always a team event. Team owners such as Ferrari, Alfa Romeo and Maserati were more concerned with victory, no matter who sat behind the wheel. Precious few drivers rose above that core truism and those that did remain the class of their age – Juan Manuel Fangio, Alberto Ascari, Jim Clark, Stirling Moss and Jackie Stewart to name some of the few. However, not every driver can be a super hero and this is a story of just some of those drivers who played a supporting role to their dominant team leader and yet, on their day, they too tasted the champagne on the top step of the podium. I call them super-substitutes. One, in particular, stands out for me, and we will come to him shortly.

During the 1950s and 1960s a different code of sportsmanship held sway. Second drivers almost always showed loyalty to their team leader. It was an era of honor and chivalry, outwardly at least. In an age when pit stops were frequent, during longer races it was a simple mattter to change drivers and a number one would, in extremis, call for a more junior driver to hand over his car and sacrifice his own race. This happened several times in Fangio’s favor when he was ‘assisted’ to two Grand Prix victories by taking over healthier cars – Fagioli’s Alfa 159 at Reims in 1951 (the pre-war Mercedes driver was so disgusted he never raced in F1 again), Musso’s Ferrari at Argentina in 1956 and most significantly of all at Monza in 1956 where Peter Collins, who also had a chance to win the World Championship, volunteered his healthy Lancia Ferrari to Fangio enabling the Argentinian to claim second place and a fourth world title.

Collins’ chivalrous behavior was matched by Moss in 1958 when he challenged protests against Mike Hawthorn at the final race of the 1958 F1 season. His honesty and decency lost Moss the title but handed it to his British rival.

Behind these headlines lie the stories of many highly competent racing drivers who for one reason or another proved to be less able or consistent than their illustrious peers. Space dictates that not all can be covered here but think Froilan Gonzales and Maurice Trintignant in the 1950s. Both two-time Grand Prix winners they even shared a Ferrari to win the 1954 Le Mans 24 Hours. However, both drove in the shadows of greats like Ascari and Moss. Enzo Ferrari was both a genius and a tyrant: He encouraged gifted hopefuls to drive beyond their abilities and in short order young guns Eugenio Castelotti, Luigi Musso and Alfonso de Portago lost their lives at the wheel of a prancing horse.

Moving to the 1960s, the rear-engined tide promulgated by Cooper challenged the Italian majors and attracted the dismissive title of ‘garagistes’ from Enzo Ferrari. Prime mover after Cooper’s two championship victories in 1959 and 1960 was Colin Chapman’s innovative Lotus team. While Chapman forged an almost unbeatable team with Jim Clark he took a leaf out of Enzo’s book by hiring a succession of capable young Brits including Alan Stacey, Innes Ireland, Trevor Taylor, Peter Arundel and Mike Spence, Jackie Oliver, John Miles, Reine Wisel, Dave Walker and more as the 1970s rolled on. A combination of Lotus fragility and focus on the true Lotus F1 heroes – Clark, Graham Hill, Jochen Rindt, Emerson Fittipaldi, Ronnie Peterson and Mario Andretti – saw all these young guns lose their seat or worse in a period of 15 years.

I mention this catalogue of drivers because although few, if any, would ever have beaten the genius that was Jimmy Clark, none of them ever won a Grand Prix despite showing huge promise in junior formulae. It was almost as if Chapman had his number one and only entered a second driver to garner the starting money.

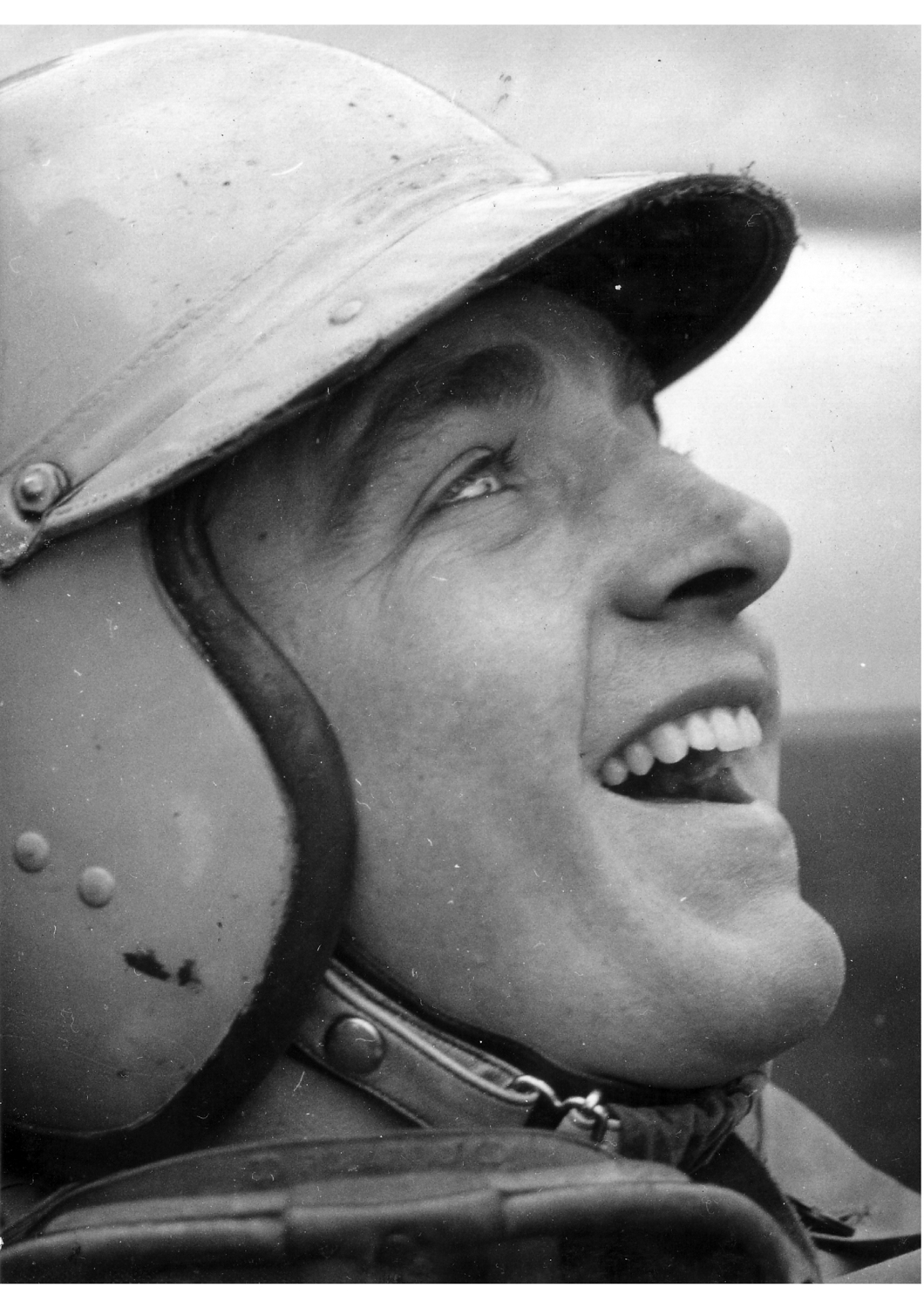

Photo: Allen Kuhn

For me, the perfect example of the super sub was Richie Ginther. Plucked out of the USA following a strong sports car career like Dan Gurney and Phil Hill before him, Ginther was spotted by Enzo Ferrari and invited to join the F1 team in1960. Apart from Hill and Wolfgang von Trips – the clear numero unos – Ginther had to share his rides in F1 with Cliff Allison, Willy Mairesse and a one-off final hurrah for Gonzales. To his credit, the Californian finished sixth in his first two GPs (Monaco and Zandvoort) and second at Monza behind Phil Hill. He also entered the record books by being the first to race a mid-engined Ferrari in his 1960 Monaco debut and quite apart from his obvious skill behind the wheel, Ferrari had noted his engineering and testing skills.

For 1961, Ginther had the good fortune to find himself in the car of the year – the fabled ‘sharknose’ Ferrari 156. He was clearly the third driver behind Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips but he did have a seat for all the races with guest drives going to Olivier Gendebien, Willy Mairesse and Ricardo Rodriguez. Despite having the development car with the 65-degree V6 engine at Monaco Ginther was Ferrari’s star driver that day. He qualified second behind Stirling Moss’s underpowered Lotus 18 but ahead of his team leaders in full 120 degree powered cars.

At the start he leapt into the lead at the Gasometer hairpin and led for several laps before an inspired Moss took the lead. The Ferrari closed a ten second gap to 3.6 seconds after an exhausting 2 hours 45 minutes of full-on battle but Moss was not to be denied on one of his most special days. Ginther had the honour of sharing fastest lap with Moss, both almost three seconds below Moss’s pole time. Phil Hill was 41 seconds back in third while von Trips finished a distant fourth.

On this performance it appeared that the freckled Californian with a crew cut was a new star driver but consistency was not to be Ginther’s forte. He finished fifth at the Dutch Grand Prix, third at Spa in a Ferrari 1-2-3-4 (taking fastest lap in the process) and retired at a scorching hot Reims French GP along with Hill and von Trips leaving victory in the old 65-degree car to Grand Prix debutant Giancarlo Baghetti. He followed up with third at the wet British GP, an off-form eighth at the Nürburgring and retired at the tragic Italian Grand Prix in which von Trips lost his life. The 1961 report card says Ginther showed flashes of brilliance but not the consistency that earned Phil Hill the title. He finished a rather underwhelming fifth in the championship behind not only Hill and Trips but also Stirling Moss and Dan Gurney’s Porsche.

However, Ginther’s performance had attracted the attention of BRM and he moved for 1962 into the de facto number 2 seat at the perenially underperforming British team. And he did so at just the right time. With both Lotus and BRM sporting new high-revving 1.5 liter V8 engines. The season was a head to head between Graham Hill’s BRM and Jim Clark’s lithe Lotus 25 with only Bruce McLaren’s Cooper and Dan Gurney’s Porsche stealing one victory apiece. So, what of Richie Ginther’s season in another championship winning team? Of the nine Grands Prix his highest finishes were a second and a third otherwise he was out of the points or retired. He finished a lowly 8th in the points leaderboard but, interestingly, two places higher than Jim Clark’s teammate Trevor Taylor. Does this tell us, perhaps, that resources were stretched in both teams and maximum effort went behind the team leader? Perhaps so, because 1963 brought better results for Ginther.

Using essentially the same car – the P57 BRM – Richie Ginther could have been World Champion….were it not for one Jim Clark. Clark almost beat Graham Hill to the 1962 title but he made sure of it, in 1963, with seven victories leaving just two to Graham Hill and the only other race to John Surtees, now Ferrari mounted. In a show of great consistency, Ginther took three 2nd places, two thirds, two fourths and a fifth outscoring team leader Hill by five points before an arcane rule deducted his lowest two scores leaving Ginther third in the championship. The innovative monocoque Lotus 25 was the dominant car and with Clark finishing every race, BRM stood no chance. But Ginther was the top scoring American well clear of Dan Gurney, Jim Hall, Hap Sharp, Tont Settember, Phil Hill, Masten Gregory, Rodger Ward and Frank Dochnal (don’t ask).

For 1964, BRM too, presented a monocoque car – the P61 later known as the P261. Ginther again backed up team leader Hill and it was a much closer race for the title with Clark suffering much poorer reliability with the Lotus 25 and 33. The Scot still won three Grands Prix to the pair for Hill, Surtees and Dan Gurney in the much more competitive Brabham BT11. At a tight final race in Mexico where any of Hill, Clark and Surtees could have won, Big John’s Ferrari took the ex-biker to the title and the Constructor’s championship courtesy of a lucky victory for Lorenzo Bandini, in Austria. Our man Richie took a pair of seconds, including Monaco for the fourth year in succession, and three fourth places to tie on points with Bandini and take fifth place in the series. Still no win though.

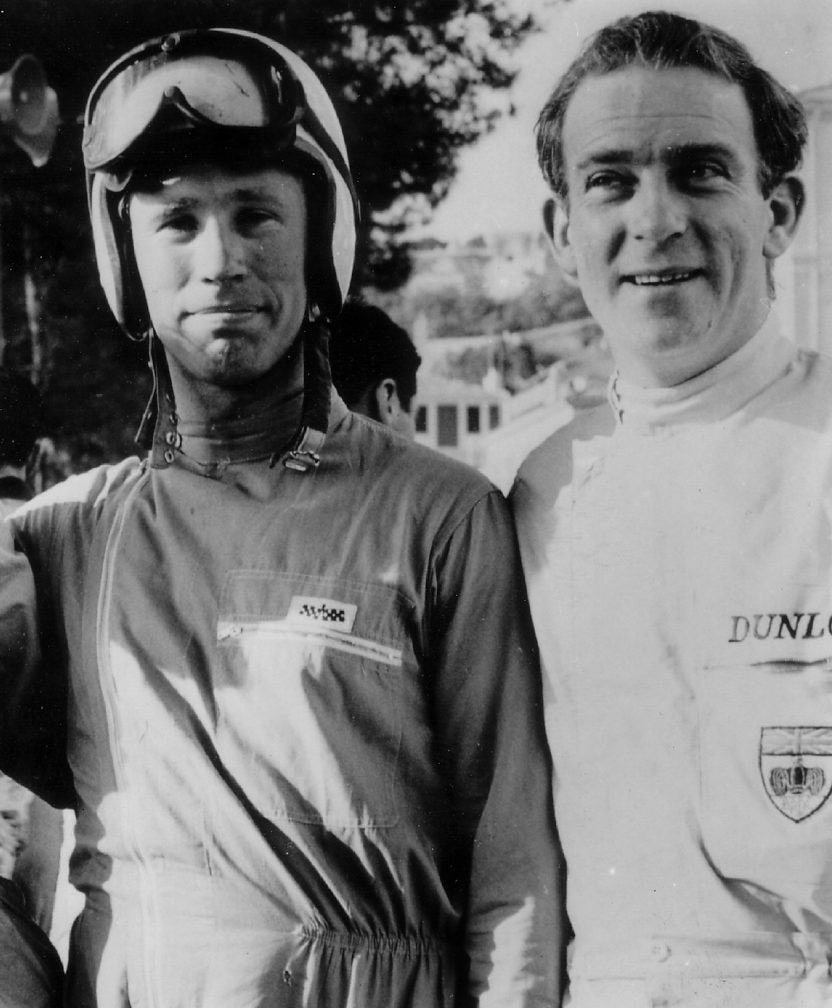

During 1964, a new Grand Prix car made its debut. Honda built a rather cumbersome car sporting a high-tech transverse V12 engine. This was driven by an American plucked from obscurity (at least to European observers’ eyes) – Ronnie Bucknum. Although it only started three times, rapid improvements showed Honda was on to something. Back at BRM ‘the next big thing’ was a young Jackie Stewart who was quickly snapped up by the Bourne team for 1965 leaving Richie Ginther without a drive. Honda swiftly hired Ginther as team leader in the hope that he could develop the RA272 into a race-winning machine. Honda also broke ranks with the Dunlop monopoly by taking on American Goodyear tires as its supplier.

Although it was another year of domination for Jim Clark and the peerless Lotus 33, Ginther plugged away through the early races with the Honda getting faster and faster. Qualifying fourth at Spa, Ginther finished sixth for Honda’s first points.

He qualified third at Silverstone, but retired and qualified third again at Zandvoort with a sixth place finish, then third again at Watkins Glen.

By this point in the season the Honda was getting both faster and more reliable and at the last race in Mexico City he qualified third once again but this time won outright. Richie Ginther the ultimate super sub won his first and only Grand Prix: he won the first for Honda and for Goodyear in the very last event for 1.5 liter Grand Prix cars.

As the size of engines doubled for 1966, many teams were not ready with bespoke cars. Honda didn’t get its 3-liter RA273 running until Monza. In the interim, Ginther drove two races for Cooper in their bulky Maserati-engined car, retiring at former happy hunting ground Monaco and finishing fifth at Spa in a rain-blighted race. Richie ran no further races with Cooper since Ferrari departee John Surtees took over his seat for Reims. The Honda V12 arrived at Monza and Ginther qualified 7th but crashed. At Watkins Glen, the Honda failed again, but in Mexico the car was on song and Ginther finished fourth having qualified third: he also took fastest lap.

Things were looking up for 1967 but sadly not for Richie Ginther. ‘Big John’ Surtees was hired by Honda and once again took the American’s seat. So Ginther joined fellow Californian Dan Gurney in the glorious Eagle for the Race of Champions where he finished second and third in the two heats before failing to qualify for the Monaco Grand Prix. With that Ginther left the Grand Prix scene, never to return. It was an inglorious end to a career that saw a great sports car racer come to Europe to drive for Ferrari, BRM Cooper and Honda and to achieve a Grand Prix victory, 14 podiums and 107 Championship points.

Following an incident in practice for the Indy 500 Ginther retired to live the bohemian life as a peripatetic caravanner with his wife. A cheery, happy-go-lucky man with great ability but a love of freedom succumbed to a heart attack in 1989 at the early age of 59. For me he typifies the many racers who came close to the ultimate prize but played the supporting role with grace, stepping up to the plate whenever needed.

He also coined the most amusing quip in motor sport after driving the Lotus 40 sports car – “a Lotus 30 with ten more mistakes.” Who doesn’t love a racer with humor.