1983 Tyrrell 012/01-Cosworth

Since the inauguration of the modern Formula One World Championship in 1950, there have been many occasions when the governing rules of competition have been stretched, or even broken, by entrants. From the mid to late 1960s, the advent of sponsorship offering pots of money to the most successful teams accelerated both innovation and exploration of the many loopholes in the regulations. Over the years, in a zealous effort for victory, Grand Prix teams, designers and drivers have more than eclipsed E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey with their smudging, bending and, in some cases, downright cheating. This was affirmed to me some years ago when I asked John Barnard how one would go about winning an F1 World Championship. His very frank and forthright reply came instantly, “Cheat!”

While there are those who bend the rules, there are also those who innovate within them, or their interpretation of particular directives. Cooper’s move against the standards of the day with its T43 blew the opposition away with a revolutionary, small, mid-mounted engine car, which saw developments through the T45 and T51 models and led Sir Jack Brabham to winning two World Championships. It also changed the whole face and thinking of the sport. With a background in aviation, Colin Chapman could be referred to as “Mr. Innovation” as his Lotus F1 cars brought many things to the table—the Lotus 25 broought the advent of the monocoque chassis, the Lotus 49 incorporated the Ford DFV engine as a stressed member of the chassis and over many models of GP cars, he explored aerodynamics from the crude high wings to the evocative cars such as the Lotus 72 and the ground-effect Lotus 78 and 79 cars. Brabham’s Gordon Murray went one stage further with the Brabham 46B, or “fan-car,” but after winning one race, team principal Bernie Ecclestone elected to withdraw the car prior to a ban being imposed. Tyrrell, through the pen of Derek Gardner, was the famous exponent of six-wheeled racing cars with the P34. Although winning the Swedish GP, the innovation faded due to Goodyear subcontracting out the making of the small front tires to another company, but failing to supply state-of-the-art rubber compound to the contractor. In the final races of the P34 era, the rear tires were two seconds a lap faster than the fronts! Advanced and improved technologies are all part of motorsport, it’s how designers, teams and drivers explore the competitive boundaries—even though they may sometime overstep those boundaries. However, when the governing body uses these grey areas to manipulate the rules, that’s another matter.

Ken Tyrrell

There have been many column inches written about Ken Tyrrell, the archetypal British team manager synonymous with Jackie Stewart’s three F1 crowns (1969, 1971 and 1973). He was a very patriotic man, Stewart once said, “I could imagine Ken wearing Union Jack pyjamas and standing to attention beside his bed, a 78 rpm gramophone record playing God Save the Queen, before retiring for the night. He was a loyalist to the core, a very special man whom Great Britain and its motor sport community were blessed to have.” Tyrrell served his country as an RAF engineer throughout World War II, as a Flight Sergeant flying Halifax and Lancaster bombers. Midway through the war years, in 1943, he married Norah Harvey, the love of his life and such a paramount part of the Tyrrell Racing team in later years. He left the RAF with an exemplary record.

After the war years, Ken joined his father, Bert, in the family business lopping and felling trees—hence his nickname “Chopper.” The wood yard was also to become a pivotal piece of the Tyrrell Racing team, too. The final ingredient was his passion for motor racing, which was sparked by a trip to the 1951 British Grand Prix. Like every Brit, he was hoping for great things from the BRM entry, with Reg Parnell and Peter Walker behind the wheels. Parnell finished 5th despite suffering leg burns from an errant exhaust pipe. Nevertheless, it was the sight, smell and all those ambient things touching all the senses that infatuated Tyrrell, especially the 500-cc race, which that day included a certain B. C. Ecclestone. He convinced himself he could do much better than most of the midfield runners. To that end he purchased a Cooper-Norton and tried, with some degree of success.

By 1959, the realization came that he wasn’t going to be a leading driver, despite some quite good results, so Ken decided to form his own Cooper Formula Junior team from the Tyrrell Brothers woodshed. Finding his niche in team ownership, things went from strength to strength. He significantly identified the talent of a young Scot, John Young Stewart, who raced in the Tyrrell Formula Junior team in 1963. The pair were reunited, in 1968, when Tyrrell agreed to a joint venture to run Jean Luc Lagardère’s Matra cars, powered by the new Ford Cosworth DFV engine that had made a successful debut with Lotus at the 1967 Dutch GP and sponsored by French Petroleum giant Elf and Dunlop tires. This was all done under the banner of “Equipe Matra International.” Despite the finance and grandeur, Tyrrell’s team was essentially a “family affair.” Keen to get on the grid for the Grand Prix season’s first race—the South African GP in Kyalami on January 1, 1968—Tyrrell ignored noises from France when he entered the Matra MS9, still painted in green primer and cobbled together to get ready to race. Stewart put the car on the front row of the grid and led some of the opening laps. An oil cooler failure scuppered what might have been a dramatic debut in the top echelon of the sport.

The next race wasn’t such a hurried affair and the new MS10 was ready for it, some four months later, in Spain. Unfortunately, Stewart was sidelined due to a wrist injury and replaced by Jean-Pierre Beltoise in the interim. Eventually, things came good at Zandvoort, when Stewart was ready to race despite his wrist being in a plaster cast. The racing gods smiled on him by delivering an atrocious day weather-wise, with rain and low clouds coming in off the North Sea. The Dunlop wet tires were great in such conditions and by lap four Stewart edged his way to the front of the pack from his second-row start. Staying there until the flag, he took the first of Tyrrell’s 33 race victories. With further wins in Germany and America, Stewart finished runner-up to World Champion Graham Hill that year, with the team finishing 3rd in the Constructors Cup, behind Lotus and McLaren. Tyrrell’s Matra and Jackie Stewart dominated the 1969 season, both winning their respective World Championships. It was a honeymoon period for the team, as were the next four years with two more World Championships added to the team tally—both of them with a Tyrrell chassis designed and built by Derek Gardner. The “garagistes,” as they were called by Enzo Ferrari, had not only taken on, but beaten, other more established teams. However, disaster at Watkins Glen in 1973—with the death of the very promising François Cevert—left the team devastated and sadly on the road to decline, from that point. Those heady days were not to be repeated, although the stoic nature and bloody mindedness of Ken Tyrrell would never see him give up trying.

Prologue to the Tyrrell 012

So, in 1983, we’re 10 years down the road from that last World Championship success. Although sporadic, the Tyrrell Team has flirted with success and Grand Prix wins, notably with the innovative six-wheel Project 34 car in the hands of Jody Scheckter and, indeed Michele Alboreto, had taken win number 32 for the team at the 1982 Caesars Palace GP, held in the hotel’s Las Vegas parking lot. Times were a changing on the F1 front, as by then the turbo-engined cars had made a dramatic impact on the sport with many major motor manufacturers backing the teams in terms of finance and engineering excellence. When the Renault turbo car made its debut at the 1977 British GP at Silverstone, Tyrrell had scoffed at the idea. The “Yellow tea pot,” as it had been nicknamed due to it forever boiling over, was looked upon as another “white elephant” advancement. Tyrrell could not see the dominant Ford DFV ever being beaten. However, overheating, turbo lag and the many inherent problems associated with such engines were quickly overcome and they were soon dominating the sport, bringing with them serious wealth from the likes of Renault, BMW, Honda, Alfa Romeo, TAG-Porsche and Fiat in the guise of Ferrari. Ken had continued to bang the drum for the normally aspirated cars and Ford was in the process of providing him with a new DFY-spec engine, which gave a good increase of power and harmonized with the light chassis of the Tyrrell 011.

Tyrrell had money too, with sponsorship from Benetton for 1983 and the sponsor’s name and livery engulfing the car. With two good drivers in Michele Alboreto and Danny Sullivan, the team was set to make an impact on the World Championship, despite having an underpowered engine. Beset with mechanical issues and overwhelmed by the powerful turbos, there was a twinkling of light at the end of the tunnel. On June 5, 1983, in Ford’s backyard, Alboreto drove the Tyrrell 011 to victory, beating Nelson Piquet’s Brabham-BMW turbo. It was the first win for the new DFY, bringing the Ford tally to 155 overall wins. More importantly, it was a breath of hope for the team, who were about to launch their first carbon fiber chassis—the 012.

Derek Gardner had been gone from Tyrrell’s employ for a number of years by then, the beheld view being that the six-wheeler had become an embarrassment and was too much for Ken Tyrrell to swallow. The 1977 season had been the first when the team from the Surrey lumberyard had failed to visit the top step of the podium since its inception. To be fair to Gardner, I’m not too sure he was given the proper acclaim for his achievements with the team, nor opportunity to complete the work required to develop the P34, or something new. The relationship between Tyrrell and Gardner had soured irrevocably, and after a period of “gardening leave” the pair parted. Gardner’s replacement was Maurice Philippe, whose roots stemmed from the De Havilland Aircraft Company, and then to Lotus working with Colin Chapman during the days of the Lotus 49 and 72 cars, though he’d also worked on the Louts 56 turbine car.

In 1972, he went to the USA working on designing Indycars for Parnelli Jones, and then drew the Parnelli VPJ4 Grand Prix car for Mario Andretti. His first work for Tyrrell was the 008. It gave the team a 4th-place finish in the 1978 Constructors Championship and Grand Prix podiums for Patrick Depailler—including a win at Monte Carlo. During the intervening years his cars had jogged along picking up the crumbs from the ever-increasing turbo table. Given the David vs. Goliath successes of the 011, daring to beat the new fire-breathing monster turbo cars. While it may not have been the fastest car, Philippe felt the nimble 012 offered a degree of challenge to the turbocharged brigade.

Benetton Tyrrell-Cosworth 012

On its first appearance at a Grand Prix event, at the Österreichring, for the Austrian GP in mid-August 1983, the new car immediately caught the attention of many a team manager due to the configuration of the unusually large rear “delta” wing. Had Philippe found something others had missed? Unfortunately not, as the theory behind it didn’t work in practice. The 012 was both slimmer and shorter than the 011, it was lightweight too, with its new carbon fiber honeycomb monocoque by the UK Company, Courtaulds. Carbon fiber had begun a march into F1 via McLaren when John Barnard’s MP4/1 used the technology to great effect, even successfully crash testing it during the 1981 Italian GP at Monza, with John Watson happily walking away from a horrendous accident. Tyrrell 012 was again powered by the new Ford Cosworth DFY normally aspirated engine, developed by Mario Illien, that offered a higher rev limit than the DFV. Ken Tyrrell was dead against turbo engine power, he’d been offered deals by BMW and Brian Hart, but refused to embrace it in the knowledge that it was so expensive to develop and run. As far as Ken was concerned, he’s on record as saying, “Maurice Philippe built a car around that (Cosworth DFY) engine. It was nimble and very easy to drive, which was important for us. We had young and inexperienced drivers at that time and it meant they could settle quickly. When we got to places like Monte Carlo or Detroit, where power wasn’t a premium, we could close the gap.”

Sporting a more conventional wing the car made its second outing in the Dutch GP at Zandvoort. This time Alboreto qualified 18th, with teammate Danny Sullivan, still in the 011, further back in 26th place out of 29 starters. The race had mainly turbos at the front, with John Watson’s normally aspirated McLaren-Cosworth spoiling the party. A jubilant Alboreto, in the new 012, picked up the final point on offer. With no points at Monza, the penultimate race of the season, the European GP at Brands Hatch found both Alboreto and Sullivan in the new cars. Recently, speaking to Sullivan, I asked him about the difference between the 011 and 012 chassis. He explained, “There was no appreciable difference between the 011 and 012 chassis as far as I was concerned. The major step forward for us was the new DFY Cosworth engine given to us during the early part of 1983. We found a significant increase in power, not as much as the turbo boys were getting, but still a good step forward.” Unfortunately, the Brands Hatch race finished with both cars retiring. The last race of the 1983 season was the South African GP at Kyalami. The 012 cars finished qualifying with Alboreto in 18th place and Sullivan 19th. At the end of the race, Alboreto had retired with engine problems and Sullivan finished a very creditable 7th, albeit two laps behind the leaders.

Photo: Peter Collins

1984, Tyrrell’s “annus horribilis”

Sponsor Benetton had walked away in favor of the Alfa Romeo F1 team. They had pleaded with Tyrrell to use a turbo engine, but his intransigence and disregard for a turbo made the clothing company lose patience with him. Ferrari saw the talent in Alboreto and signed him to replace Patrick Tambay. Danny Sullivan was left in limbo, but eventually signed to race in the U.S. Indycar series (see Legends Speak for his full story). This left the Tyrrell team driverless, but having offered Martin Brundle—the man who had dared to beat Ayrton Senna in the 1983 British F3 Championship—a test drive, in which he proved himself to be more than up to the task. Despite being cashless, Brundle accepted Tyrrell’s F1 contract and German driver Stefan Bellof joined him.

Behind the scenes, there was a more sinister issue, which would eventually define Tyrrell’s 1984 season. One of the regulations for 1984 was a minimum weight limit, which most teams could achieve quite easily, but the Tyrrell 012 being the only normally aspirated car on the grid, had issues with it. Compounding the problem, the turbo teams had suggested the amount of fuel carried should be reduced from 220 gallons to 195 gallons. However, due to the Concorde Agreement, a binding contract between the FIA and F1 teams, there had to be a unanimous agreement among the teams before any rule change could be sanctioned. Of course, reducing the overall weight of an already very light car would have significant disadvantages to Tyrrell. Backed by rich major motor manufacturers, frustration began to gather against the tiny garagiste constructor from Ockham, but Tyrrell held firm and raced on.

The opening race of the 1984 season was at the Autodromo Jacarepaguá, Brazil, it followed a 10-day test where all teams could ensure their cars were raceworthy and new drivers could get acquainted with their teams. Brundle and Bellof dealt with the sweltering tropical heat and humidity quite well, with both cars qualifying to race, Brundle 18th and Bellof 22nd. Race day brought the F1 race debuts of the Tyrrell boys, and also that of local lad Ayrton Senna, in the Toleman team. Senna lasted just eight laps and Bellof 11, before retiring with engine problems. Brundle, however, was going very well. By lap 31 he was in an amazing 7th place and by the penultimate lap he was 6th, about to score his first World Championship point. On the last lap, Brundle moved up one more place and finished 5th, earning two points on his debut. Brundle said, “Ken was wearing that seven-inch-wide grin he had. He was really happy. I think we were all slightly bemused.” The next points earned by the team were thanks to Bellof, finishing 6th in the Belgian GP, Round Three of the Championship, and 5th at the following race at Imola. Brundle was unfortunate not to have scored points at Imola too, but fuel starvation caused his retirement.

The “jewel in the crown,” the Monaco GP, is the race where every driver wants to do well. Organizers of the race had reduced the field to just 20 runners out of the 27 entrants, so qualifying to race was paramount—almost a case of do or die you may say. And that’s more or less what happened to Brundle in his attempt to qualify for the race. He explains: “I came through the chicane leading to the harbor front faster than I had done before. The lap had been inch-perfect. The chicane was bloody near flat out in our car, which meant arriving into the left-hander at Tabac at some staggering speed. The brake pedal went soggy. I had touched the curb somewhere and got a bit of knock-off on a pad. The brake balance bar used to run in front of the throttle pedal. As the brake pedal went down it took the balance bar cable with it, across the throttle. As I tried to brake, I actually accelerated, straight into the barrier.” In essence, losing control Brundle hit the Armco with a colossal thump, the car flipped onto its side and slid down the track. The right-side wheels were totally ripped off. As for Brundle himself, cocooned in the cockpit his head took a massive blow as the car flipped. When the marshals were able to get him out he was still conscious and frantic to get back to the pits to get in the spare car to continue his qualifying. On his arrival back at the pits, Ken Tyrrell soon realized his driver was in a confused state and in no shape to continue.

The 1984 Monaco GP was the famously wet race where cars were continually falling off the track, the attrition rate was high due to appalling wet weather, which made driving conditions some of the worst experienced for many a year. Monaco had probably seen similar, in 1972, when Beltoise’s BRM took victory. By lap 27, Alain Prost was in the lead, but was in danger of being overtaken by Ayrton Senna in the Toleman-Hart and just behind Senna was Bellof, who’d qualified on the last row of the grid! His 012 was at full chat, lapping faster than the top two. Clerk of the course Jacky Ickx saw conditions were becoming dangerous and red-flagged the race, leaving both Senna and Bellof mortified due to their race pace and position. This left Prost the victor, and years of enthusiasts pondering over what might have been.

1984 Detroit GP

The Detroit Grand Prix, the next race on the 1984 World Championship calendar, was the real game changer for Tyrrell. Ken had been very vocal in his opposition to turbocharged engines for a number of years. His car was the only normally aspirated car on the grid, and whatever tiny advantage he felt he may have was continually being marginalized by the on-track power of the turbos and the behind the scenes politicking from the major manufacturers needling Tyrrell to agree to the reduced fuel capacity, though a reduction in the volume of fuel would render the 012 too light to race. Feeling like a rabbit in the headlights, he began to look at those grey areas like many other teams had done before and many more since. As such, the team devised a system where water was taken on board in a separate tank, supposedly to spray over the engine air intake to aid cooling. The regulations seemed to allow replenishment of these tanks prior to the checkered flag. To make weight at the end of the race there was an addition to the water in the form of lead shot pellets. This mixture added some 140 pounds in weight and ensured the car would be well within the minimum regulation requirement at the finish. It was pumped on board the car, via a device the mechanics referred to as the “duck gun.” It consisted of an air canister and two water cylinders with large pistons inside. As the car came in during the final laps of the race the mixture was pumped in under pressure. This pressurized system had to have a vent to aid a successful transfer. Occasionally, this vent spewed out surplus water and lead pellets, which caused concern to many other teams. It’s not too clear when the system was first used, but it was certainly in place at Imola. It’s also not certain that the drivers were aware of the system. Martin Brundle said, “…I was incredibly naïve then. The first I knew was when someone asked me about this lead shot, which was all over the Tyrrell pit after I’d made a stop! I hadn’t the faintest clue what they were talking about. But I have to say I did wonder why it was so necessary to take on all that water close to the end of a race and then suddenly have the car feel like it was towing a caravan as I left the pits!”

Photo: Chris Willows

The Tyrrell drivers both qualified a little better than their usual positions, Brundle 11th and Bellof 16th, mainly due to the tight street circuit layout. As the race progressed, Bellof crashed out, but Brundle was taking the race to the turbo cars. With 18 laps of the race to go he was 4th, rising to 3rd after Alboreto’s Ferrari retired and 2nd after a perfect overtaking of Elio de Angelis’ Lotus. Now Brundle had leader Nelson Piquet in his sights, but the laps were running out and he had to settle for 2nd place. “One more lap and I would have won the race,” said an ecstatic Brundle.

Following the conclusion of the Detroit GP, samples of fuel and water from the extra tank, in the case of Tyrrell, were analyzed. The turbo teams thought the Tyrrell had been running underweight for the majority of the race and this is how the Tyrrell success could be explained; the “splash and dash” for extra ballast in the dying laps of the race simply made the car race legal. While Ken Tyrrell admitted the lead shot was legal ballast, the authorities were gunning for him and claimed the water contained a percentage of hydrocarbons and deemed it to be a fuel. As refuelling was illegal, the Tyrrell team had breached the rules and was disqualified. Lengthy court battles ensued, with Ken vigorously defending his position. The final appeal hearing was held where FISA completely refuted Tyrrell’s compelling evidence. Eventually, the international judges found him guilty and served him with the severest of penalties—a total ban from the 1984 World Championship. The team lost its 13 points tally and lost the financial backing of FOCA’s travel allowance. Disqualifying Tyrrell from the World Championship allowed the F1 teams to carry out the wishes of their major motor manufacturers and reduce the amount of fuel carried, without Tyrrell, the Concorde Agreement now had its required unanimous support. A means to an end you may say? The Tyrrell team had obtained a court order to enter further races during the 1984 season, but all results were expunged at the final hearing. The team didn’t run after the Dutch GP at Zandvoort.

Photo: Chris Willows

For the 1985 season Tyrrell finally bent toward using turbo engines. Ironically, it was Renault that supplied them. Martin Brundle and Stefan Bellof kept the faith with the team and continued for a second year, although Stefan Johansson deputized for Bellof in the first Grand Prix of the year. The 012 continued with Ford DFY power until mid-season, when the new 014 turbo was launched, although now in its third year it was virtually ineffective as a point scoring machine. Having said that, Bellof scored one point at Estoril in the Portuguese GP and a further three points at Detroit—the last points 012 would score. Sadly, Stefan Bellof lost his life driving a Group C Porsche at Spa. While Tyrrell lost a driver, the world undoubtedly lost a future champion.

Driving 012 chassis 01

Historic motor racing is the conduit for keeping the racing cars of the past alive and kicking for future generations to admire. Given its record, you could say this car cheated the championship, but that’s far too cruel and callous to discredit 012 like that. It has surely earned a significant place in Grand Prix history as being Tyrrell and Cosworth’s last stand against the mighty turbos. As the car sits on the pit apron, one’s mind is cast back to an era when men, not computers, designed cars. Maurice Philippe’s minimalist contender bears a certain resemblance to the Brabham BT52 penned by Gordon Murray, but closer examination finds the Tyrrell more compact than the Brabham, with a seven-inch shorter wheelbase and narrower track front and rear. Polished, warmed and ready for action it’s a shame the car wasn’t on a more level playing field in period, because it exudes all the charisma of a race-winning car. Like Joseph in biblical times, this car wore coats of many colors, but today it’s in Benetton livery just as it was when first launched to the press, but sans the delta wing (although the current owner may look at producing one at some stage).

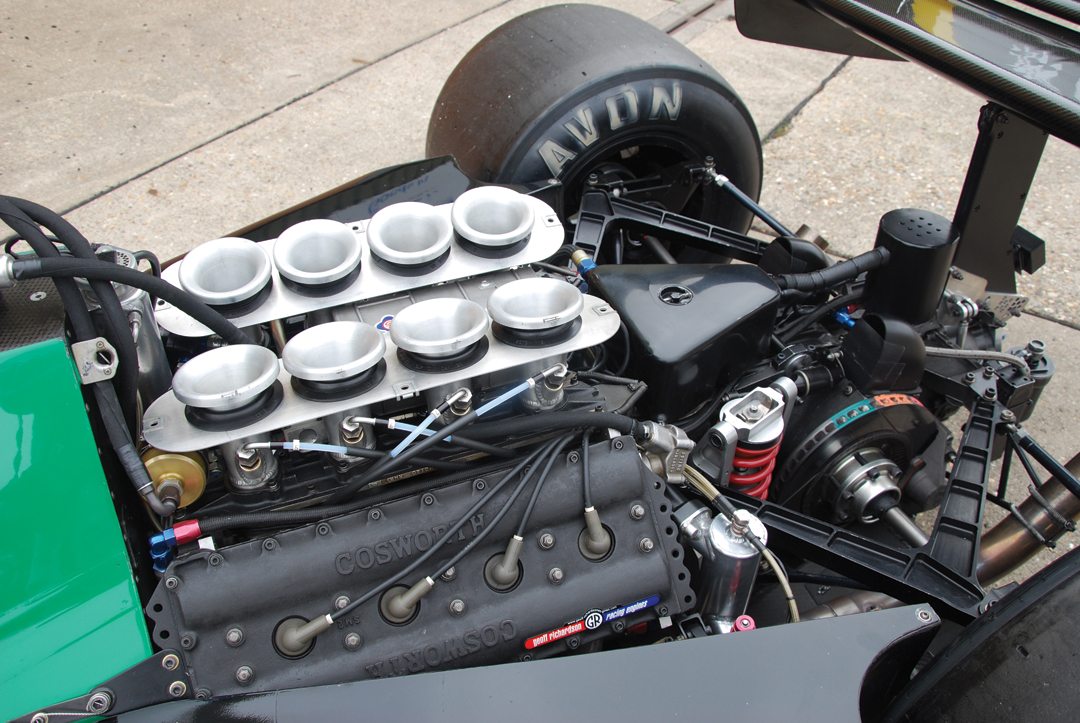

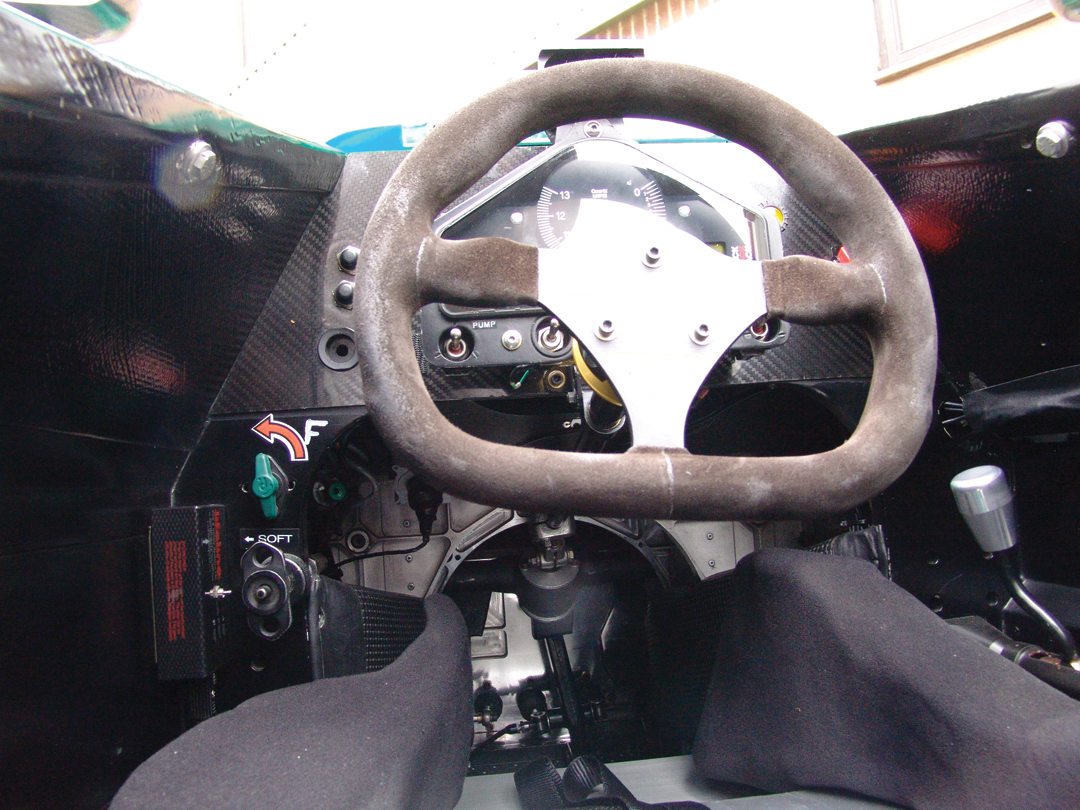

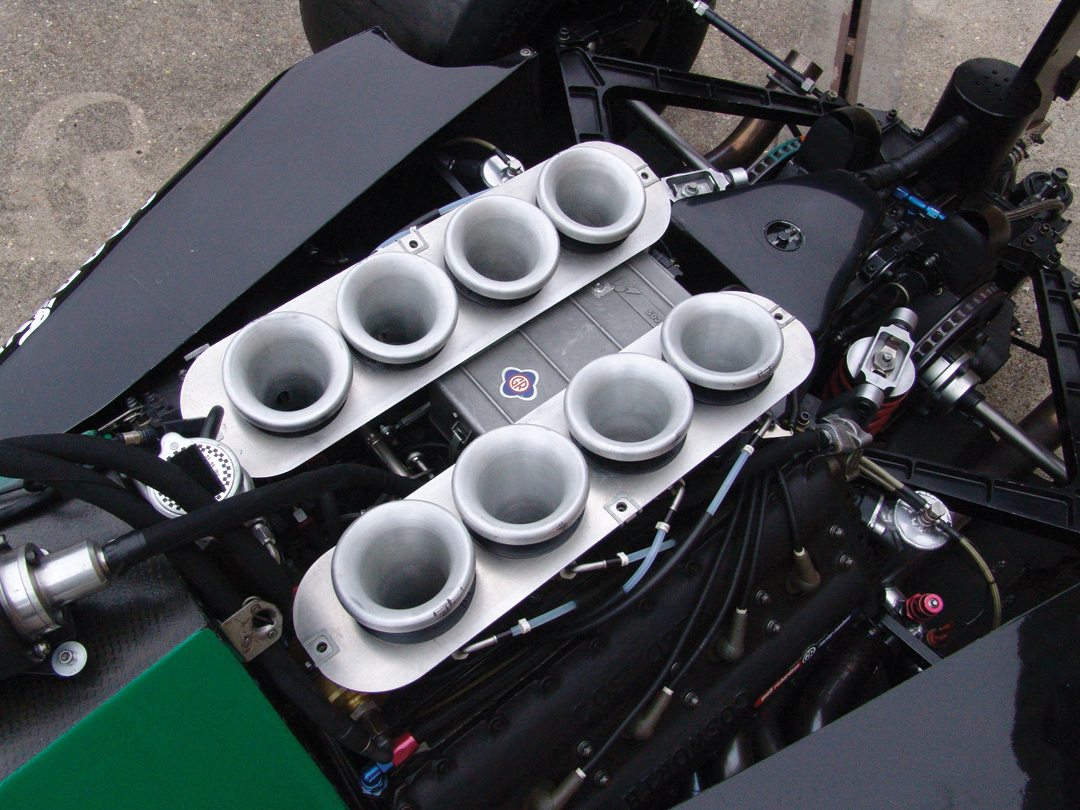

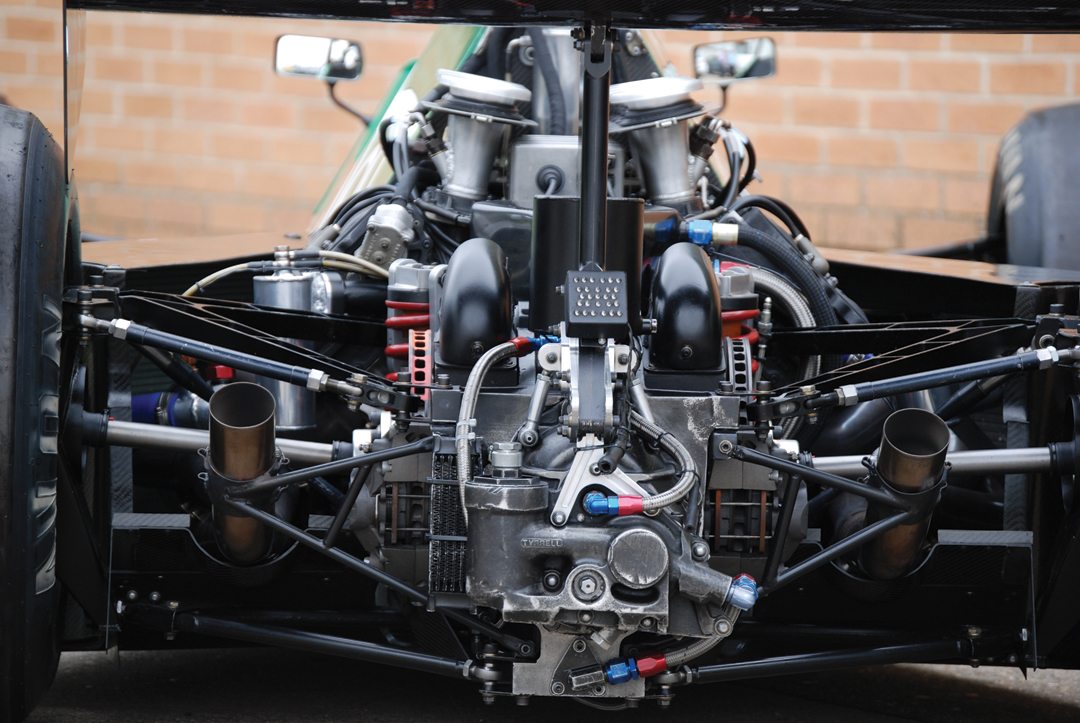

Our car is the same one as debuted by Michele Alboreto, at the 1983 Austrian GP. Stepping in, the driver compartment is small, but adequate, although it’s obvious the car was meant to carry a diminutive frame—drivers above 65 inches tall needn’t apply! Sitting as low as possible is an order of the day, trying to keep shoulders inside, rather than outside the cockpit is distinctly beneficial, as are tiny feet to operate the foot pedals. Once seated, belted and settled in the cockpit, the rev counter is clearly visible through the top half of the Momo steering wheel. In comparison to today’s F1 cars, the steering wheel is quite naked and the dash adorned by a negligible amount of necessary buttons and switches. The engine installed is a DFV, rather than the DFY as in period, but still capable of providing some 500 bhp. Other than that, the car is in very similar shape to when it debuted in Austria almost 35 years ago.

We are at Zandvoort, where the 012 gained its first World Championship point in just its second race. The circuit, in layout, has changed much from 1983, and the former circuit has been developed on. However, the new circuit length is about the same, although more compact and more undulating than the original. The weather is fine and the road surface dry. It has to be remembered that Zandvoort is a coastal circuit among the sand dunes overlooking the North Sea. At times, there can be a fine film of powder on track, which will compromise adhesion—today we’re quite fortunate not to have any issues on that front. Sitting very low to the ground, it is very important to keep your gaze firmly fixed in front of you rather than to the side, as the sensation of speed messes with your senses. Being so low to the ground does have an advantage, as the apex of the corners are very apparent and difficult to miss. A couple of exploratory laps have been completed, all systems are working to temperature and we’ve been given the all clear to go for a quick lap.

As we cross the start/finish line we’re in fifth gear pulling 10,000 rpm on the fastest part of the track. Ahead is the right-hander at Tarzan, almost a double-apex corner; braking as late as possible we stay out wide to negotiate the entry to the hairpin. Taking the apex as late as possible gives ample opportunity to get on the gas to exit and drive uphill to a quick, left-right-left sequence. Here, it’s all about confidence to carry the speed through the curves. It’s then downhill aiming for the back of the pits to the Hugenholtz Bend, another hairpin. Again, exiting here with as much power as possible is critical to get you in shape for the long uphill straight. Our senses feel as though the car is unbalanced here, but in fact it’s actually holding firm. A blind crest leads into Scheivlak, apparent by the huge gravel trap in front of you, which can be disconcerting. Things remain relatively easy from this point until we reach another tight right at Renault curve. Turning in here and allowing the car to run wide is the best way to keep momentum, but care is needed as there’s a chance of spinning if power is put on too early. Next is Vodafone, an open left-hand bend that runs down to a tricky chicane, the Audi Esses, requiring utter respect from the driver. We’re arriving at the chicane in fifth gear and pulling maximum revs. Braking is paramount here to thread successfully through the tight corners, we’re at just 65 mph at this point. Accelerating though the penultimate corner leads on to the Arie Luyendyk Curve, a point where it is critical to carry speed through onto the start/finish straight to complete the lap. A good time to beat is 1 minute 37 seconds in this car, a ground-effect car would be faster due to the aero package working and sticking the car to the track. It has been a fantastic lap, especially in the tight corners and under braking. It’s easy to understand the light and nimble characteristics and advantage the car had on the turbos in period.

It’s outrageous to think Ken Tyrrell was deemed a cheat. Like many before, he was simply applying the regulations, as he understood them. A ban for a couple of races could have been reasonable punishment, perhaps some financial penalty, but then again FISA had another agenda in mind.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: Currently fitted with Cosworth DFV 500bhp – In period fitted with Cosworth DFY 520bhp

Gearbox: 5-speed Hewland manual

Brakes: 280 millimeters vented

Steering: Tyrrell 7-tooth rack and pinion

Body: Courtaulds Carbon Fibre

Suspension: Front: Double wishbones, rising-rate coil spring dampers with pull rod. Rear: Double wishbones, coil springs

Weight: 540 kilograms/119 pounds

Wheelbase: 104 inches

Track: Front: 67 inches, Rear: 58 inches

Wheels: Magnesium, Front: 11.5 inches, Rear: 16.5 inches

Resources / Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Directory of Formula One Cars by Anthony Pritchard

Autocourse History of Formula One Cars 1969-1991 by Doug Nye

Tyrrell – Kimberley Grand Prix Team Guide

Ken Tyrrell by Maurice Hamilton

A-Z Formula Racing Cars by David Hodges

Periodicals

Autosport and Motor Sport

Thanks

Sincere thanks to Ian Simmonds for the use of his car and editorial assistance, Philip Cheek and the team at Complete Motorsport Solutions. Special thanks to Danny Sullivan for his kind assistance and factual input and lastly to Zandvoort Racing Circuit.