Engineer, Champion Rider, Champion Driver and Team Manager

Photo: Roger Dixon

Mark Donohue talked of “the unfair advantage,” the way in which a driver with an engineering background was always one step ahead of his competitors. Having started off working with his father, Jack, on motorcycles and then becoming an apprentice at Vincent, John Surtees was another such. Indeed, the only man ever to have won world titles on two wheels and four confessed that initially his main interest was in “tinkering.” Riding then was simply a product of testing and of experiencing the satisfaction of having prepared the machine correctly, or not.

It was this background that enabled Surtees to communicate effectively to the mechanics and designers of the cars and bikes he was to drive over the years. He described this ability “as the most important thing.” In his time there was no data other than a stopwatch, the tire temperatures and what the driver could impart. He never designed himself, but could talk to both the engineers and the person involved in design, which, as he pointed out, were not always the same thing. “I made suggestions, but I always looked upon them as part of team work.”

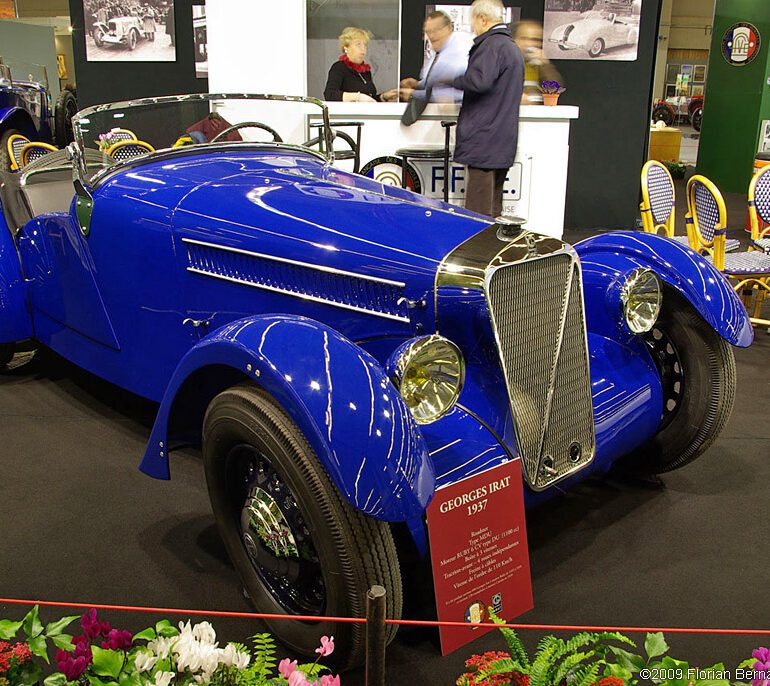

Even in his later years, Surtees regarded the most important race of his career as that at Aberdare Park where, riding his Vincent Grey Flash, he scored his first win. “Up until then I was a mechanic putting a bike together and wanting to see how it went. On that day, I came together with the bike where, in a way, it was talking to me. I was feeling it in such a way that I could push it to higher limits.”

His experience was widened when he joined Norton, where the race team was managed by “the Wizard of Bracebridge Street” Joe Craig. “Joe was not a ‘super engineer.’ What he was, was someone who had taken his riding experience forward into judging how to get the best out of the equipment.” The dogmatic Craig was basically a development engineer. “When you are working in the company of somebody like that, a little bit of it rubs off on you.”

MV Augusta was not the force it was to become when Surtees joined it. Leaves at Monza meant that his first test with the team was transferred to Modena, a track he would see so much of in the years to come. Even that test was near to being cancelled because of rain, but Surtees pointed out it could rain on race day too. The bike felt a little cumbersome and “all too soft and spongy.” It was just not positive enough for Surtees, who had been used to the superb handling of the Norton. The bike was set up high and the engine large. Surtees initially brought about change with the help of chief mechanic Arturo Magni. As having new parts made took time due to the need for agreement from Count Agusta, Surtees concentrated on such as the dampers and liaising with both Girling and Armstrong, before settling with the latter. He also had freedom to choose the tire supplier, in this case Avon.

This was the period of full streamlining—the “dustbin” fairings. Those of Gilera and Moto Guzzi, which had finely developed a fairing in its own wind tunnel, were “superb.” However, the airflow from MV’s fairing affected the engine performance. Handling was also compromised. MV was an aeronautical company and so the decision was made to use Aermacchi’s wind tunnel in Milan. “We had tufts of wool and bits of oil on the fairing, something that I took to Ferrari when we first started to test cars in 1963.” Toward the end of 1956, the MV fairings were working more effectively and Surtees was able to give the company its first World Championship.

For 1957, MV decided it wanted more mid-range power and so lengthened the stroke of the engine. This made the performance of the fairing even more critical and Surtees began to suffer piston failures. The only races he won were without the full fairing, which meant a loss of 10 mph of top speed.

Domenico Augusta used to travel to the races by train. Surtees had been trying to get improvements made to the bike’s frame, “to make it hold the front and back together better,” so he booked to be on the same train to the Dutch TT. By the time they had returned to Milan, he had the go-ahead to build a new frame. The result was one that had the best characteristics of what had been built into the 1950 Norton “Featherbed,” which had been built by the McCandless brothers. That remained the frame until 1963. When Mike Hailwood moved to Honda from MV he told Surtees that he would appreciate it if he could make the Japanese bike handle as well!

At the end of 1958, Surtees was at an awards luncheon on the same table as Mike Hawthorn, Tony Vandervell and Reg Parnell. It was Hawthorn who said, “Try a car—they stand up easier.” Vandervell said it would have to be a Vanwall. Aston Martin team manager, Parnell pointed out that Vandervell had retired, only to be given a suitable reply. Surtees did test a DBR1 and then a Vanwall, both at Goodwood. Vandervell, despite the advice of his doctors, decided to return to the sport and built a rear-engined car, specifically for Surtees, which ran just once in the ill-fated Intercontinental Formula.

Surtees’ first international car race, though after just one Formula Junior event, was in an F2 Cooper-Climax that he had bought and which he and his father prepared. He was quoted in 1960: “I notice that drivers tend to do far less of their own maintenance than riders. I don’t know much about this car yet, but when I do I shall try to carry out most of the maintenance myself.”

It was not long before Colin Chapman had attracted him into Formula One. He recalls the Lotus 18 as probably the most competitive car of his career. He liked Chapman, seeing a resemblance to Joe Craig. “There was that same certain wisdom and cryptic remarks.” Chapman was prepared to accept Surtees’ feedback. “He would just absorb things, but at that stage I was just a learner. At the outset I could go quick, but there were times when we had to find just why that was. It was an experience that influenced me greatly.”

When Surtees moved to the Parnell-run Yeoman Credit team, it was thought that it would be running the works Coopers. It was not to be and so, after a year, he suggested to Parnell that they build their own car. He felt that the closest person in his thinking to Chapman was Eric Broadley. He accordingly did a deal with the Lola founder, which he then sold to the team owners. The result was 4th in the World Championship in front of Ferrari and Porsche.

Surtees worked with Broadley on the development of the Lola Mk.4 from the start. He also pays tribute to the work of Rob Rushbrook, who built the car. The team made a massive leap forward at Spa. Surtees was having problems in a straight line. During practice, he was watching wheels being changed at the garage used by the team in Stavelot. With the Lola jacked up he noticed that the chassis was twisting. Some extra tubes were welded in around the cockpit, totally transforming the car. It continued to work well, twice winning when a 2.7-liter Climax engine replaced the 1.5-liter to enable it to race in what would become the Tasman Series. Working with Broadley on the Mk.4 was “a good learning curve,” the association continuing long after he had left the renamed Bowmaker operation.

The most obvious example of this followed a trip to America to race a stripped down Ferrari P3 in sports car events. The car was too heavy and had too small an engine capacity. Surtees told his then employer Enzo Ferrari that his team was isolated in Italy and he ought to keep abreast of what was happening elsewhere. Therefore, could he become involved in what was to become the Lola T70? There were some aspects of the project that did become useful to Ferrari including the use of Firestone tires and being able to use Specialised Mouldings for its first fiberglass bodywork.

Photo: Roger Dixon

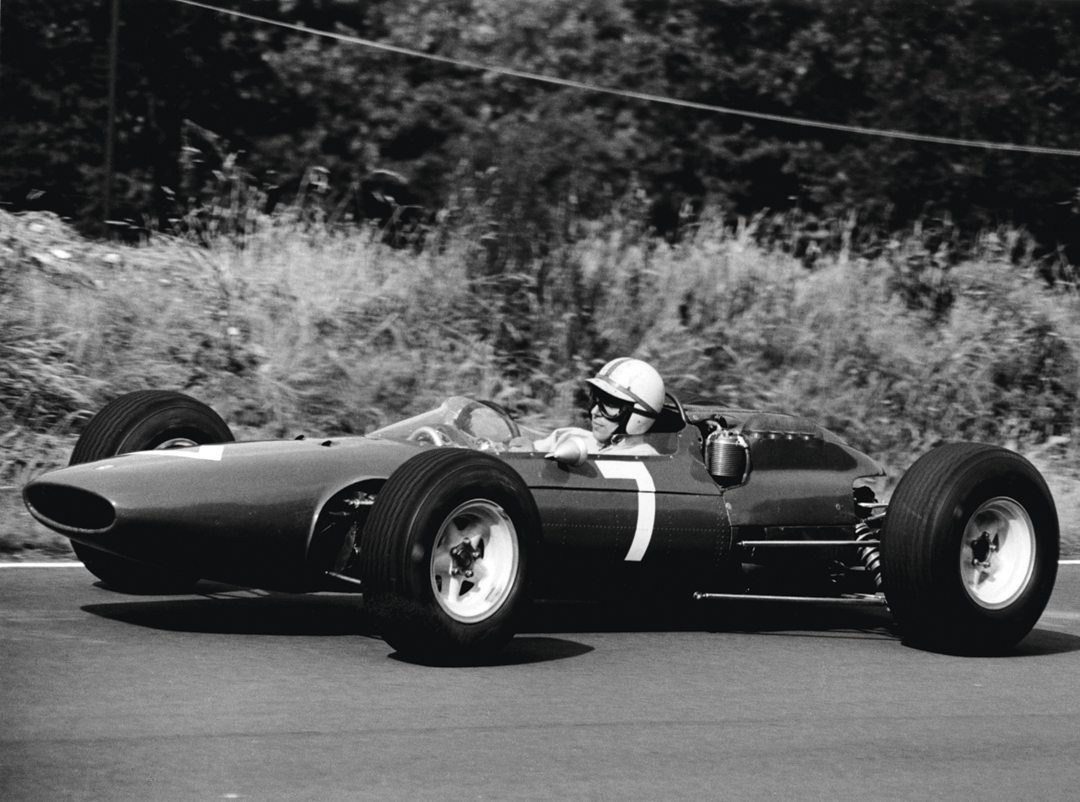

Surtees had been approached by Ferrari, which, with key team members having left to form ATS, had been in the doldrums. “They wanted a new beginning.” Franco Rocchi had remained with the team and was a “mainstay.” He had been largely responsible for designing the successful V6 engines, even if Carlo Chiti had taken the praise for them. Giancarlo Bussi was engine development engineer, while Mauro Forghieri was “a fairly new boy.” Surtees was required to carry out all the testing.

At that stage, Formula One took second place to sports cars at Ferrari. Thus, his first Ferrari drive was a prototype, which had had the chassis chopped and its V6 replaced by a V12. “From then on I went round and round Modena testing various different bodywork, which Medardo Fantuzzi (who had been responsible for the lines of the Maserati 250F) modified on the spot.” Thus, the 250P (Ferrari’s first mid-engined prototype) evolved. Surtees recalled “wind tunnel testing” being just as it had been with MV Augusta, “with the wool tufts and the oil!’ The result was “a very driveable car,” ideally suited to a type of racing of which he had admittedly no previous experience.

Development of the Formula One car took the same course, simply driving round “trying this and that.” Surtees remembered that his suggestions “were reasonably well received.” Michel May, perhaps best remembered as the first person to try a wing on a racecar, joined as a consultant and introduced Bosch fuel injection to Ferrari. Surtees had already experienced this with Vanwall and the problems of trying to get the carburetion clean through the range. Having a smaller engine, the Ferrari was even more critical. Considerable changes in performance were encountered just with a change in temperature. There was none of the consistency of performance that came with Lucas injection.

The 1963 Ferrari 156 was not, Surtees said, “a Lotus in that it was not economical in its use of the road, but it was a good, driveable car. It was more like a Cooper. If we could have consistently revved the engine an extra 250 rpm, we would have been that much better off.” Surtees would have liked full monocoque construction but “they thought that a step too far.” Instead a stressed skin chassis was built using a multiple, small section tube framework. The result took Surtees to the World Championship the following season, a result that he may well have repeated in 1966, the first year of the 3-liter formula if he had not fallen out with Ferrari.

On leaving the Italian manufacturer, Surtees again picked up with Broadley, which led to the Lola-Aston Martin Le Mans T70. “Putting what we had learned with the sports car into a GT and fitting a five-liter V8 looked like being an interesting, all-British project.” Surtees recalled that he had enjoyed racing Ferrari prototypes in the 1000-kilometer race “but Le Mans brings a different challenge.” Frustrated about the way his time with Ferrari had ended, he arranged for Aston Martin to supply its unfortunately bulky engines to Lola to enable him to “take the fight into the enemy camp.” The car was 2nd-fastest in practice at the Nürburgring, but both engines failed at Le Mans “and that was the end of the project.” Prior to Le Mans, Aston’s Tadek Marek had decided that there was a likelihood of cylinder head gasket problems and had changed the design and specification. Surtees did not discover this until after the race.

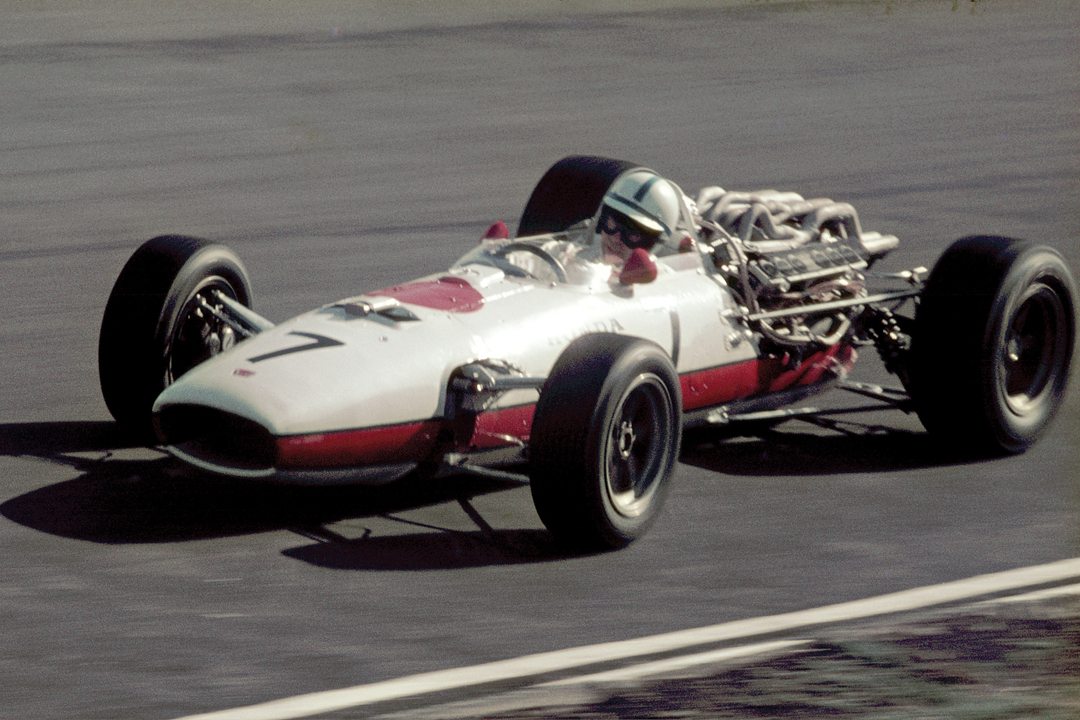

The second half of the 1966 F1 season was spent with Cooper where the designer was Derrick White, whom Surtees rated very highly. Indeed, he was to work with him again on the Honda F1 project. “He probably does not get enough credit for what he did.” Having arrived at Coopers half way through the season, Surtees made some suggestions as to how its heavy, Maserati-engined Type 81 could be improved. The roll centers were changed at the rear to suit his driving style. The year ended well with victory in Mexico. “We made the car better, but that was teamwork between me and the team.”

Photo: Roger Dixon

For 1967, Surtees went to Honda, intent on making it into a World Championship winner. When, despite his best endeavors, that came to nought, that led to an unhappy season with BRM. Surtees had had a great respect for BRM and its 1.5-liter cars, but much had changed since its 1962 world title. He didn’t say much about his brief time with the team, except to observe that it helped him to make the decision to build his own cars. He was, though, instrumental in persuading Tony Southgate to join BRM. He had worked with Southgate—who was by then in the USA with Dan Gurney—at Lola and on the “Hondola.” “I rang him up and got him to come back and join us.”

The transition to constructor “came about by accident.” Surtees had bought a Len Terry-designed Leda F5000 for actor James Garner. He still had some of the team that had come together to work on the Honda, and they did development work on the Leda, which was sent out to the USA, but the deal with Garner did not develop so Surtees decided that they should race it themselves. The Leda was developed into the first Surtees, the F5000 TS5.

“Perhaps I should have gone back to Colin (Chapman) and said let’s forget the past and start again, but I had this F5000 project, so I thought let’s build our own car.” A unit was found in Edenbridge, not far from his home. A team of local people were brought together. Ken Sears, who had been at Loughborough College, also joined. “My input was to decide exactly what we could achieve and produce, wanting to do as much as possible in house,” said Surtees.

Following his experiences with the Leda, he had certain, distinctive ideas. He spoke to Anthony Reynolds of Reynolds Tube, with whom he had been involved in his motorcycle days, as he wanted a suitable material for bulkheads. It was fortunate that the company had built all the 531-section tubing for the Jaguar E-Types and there was still plenty of surplus tube.

Photo: Roger Dixon

Surtees set down the basic specification of what was to be the TS7 (and the TS8 F5000 derivative), while Sears did the detailing. The team also gained experience of the Cosworth DFV by buying a McLaren M7. Two wedge sections were fitted to the side of that car to enlarge the fuel capacity and also lower the center of gravity.

For the TS7, “we came up with a design, using the lesson of the triangle to create the required stiffness. With a folder and L72 aluminum sheet we were able to create the chassis in house. We used the best aircraft rivets and the latest developments in epoxies.” Surtees confesses that a mistake was made with the oil tank, not allowing enough for the air and oil circulation that occurred with a DFV, and the result was oil surge, which lost the team the chance of a decent placing in its first race. “We put that first car on the grid for £23,000, and that included £8,000 for the DFV.” As the program progressed, so use was made of MIRA and a wind tunnel. Side radiators were fitted for the car’s successor the TS9B.

Photo: Roger Dixon

In Formula Two, Surtees was not allowed to have a new two-liter Cosworth engine “being such a new boy.” So a (more reliable) 1850-cc Brian Hart 420R engine was fitted “and we beat all the two-liters, which was rather nice.” The team also tried the first of Hart’s two-liter engines, and Surtees won what was virtually his last race, the 1972 Japanese Grand Prix.

Surtees’ little team stayed together until the end. During testing, in early 1973 with its new F1 car, the TS14, the first of the cars with the newly mandated crushable structures, they were quicker than Lotus. Then Firestone decided to withdraw from racing, but continue to supply tires for one year. Only one type was available, and it was not the tire that the Surtees has been fastest on. There were now problems adapting the car to work on this. The records show drivers Hailwood and Carlos Pace going quickly, but then falling rapidly away as their tires deteriorated. “It’s a shade of some of the things that are happening today,” mused Surtees.

Photo: Nick Loudon

Problems arose when a major sponsor failed to pay. Surtees went to court, but had to settle for costs. In the meantime, the team had built the “somewhat different” TS19. Surtees would have gone ground effects in 1979 with its TS21, which had been worked on with Southampton University. Health problems, though, had intervened, and Surtees sold his position in the Formula One Constructors Association to Frank Williams, enabling him to pay all the team’s creditors.

When the team closed, what was left went into a shed. This was later moved into a workshop on Surtees’ estate. The TS7 and TS10, the only Surtees car that his son Henry was to drive, were restored. When the Henry Surtees Foundation was formed after Henry’s tragic death, John decided that the rest of the cars he still owned should be reassembled and put to work for the charity.

John Surtees remained an engineer to the end of his life. As the writer arrived to conduct the interview for this article, so John emerged from an outhouse with a box of components that he was taking through to the workshop for an ex-works Norton. There was a bare TS14 tub on his premises waiting to join the other cars, although Surtees said he had become more hands-on with his bikes. In John Surtees, by then in his eighties, could still be seen the John Surtees who worked on motorcycles with his father.

Sadly, John Surtees died of respiratory failure on March 10, aged 83. It is easy to remember his unique qualification as the only man ever to win both the Formula One and the premier World Motorcycle Championships. We should also recall his undoubted qualities as an engineer, again with both bikes and cars.

Keeping Me On Track

by Divina Galica

Give & Take

The pubic attitude was that while he was without a doubt a great driver, something was odd about him. People couldn’t warm up to him. He threw away a World Championship on principle because he felt Ferrari wasn’t honoring agreements that the two men had made in private. For a book of essays eulogizing Jim Clark he wrote, “Views At Variance,” a candid and often critical appraisal of Clark’s abilities that shocked people at the time, but that today seems fair and accurate, an invaluable look at racing in the 1960s.

My first real encounter with him came in the ’66 Mosport Can-Am. I had outqualified him and started a row ahead, yet he blamed me for hitting him from behind. The papers picked up the story, and Monday morning I was the villian who had wrecked the great hero.

Five days later, I was in the paddock at Watkins Glen when Surtees pulled in and motioned me over to his rental car. Silently, he unfolded a newspaper, and there was the picture of someone else’s car ramming into the back of the Surtees Lola. He never apologized, because that wasn’t his style, but we both knew he owed me one.

The chance came at the ’71 USGP. I had been running his F5000 car and doing well. All summer my chief mechanic, Jack MacCormack, kept nagging Surtees until at the last minute he offered me a drive in the team’s third car. F1 had been my dream; now it was coming true—or so I thought. The seat had opened up because the regular driver, Rolf Stommelen, was injured. Unbeknown to Surtees, Stommelen’s sponsor had picked Le Mans winner Gijs van Lennep to replace him, and he was already in the air. Now Surtees had two drivers—one paying for his ride and one who wasn’t. I didn’t think I had a chance, but here was Surtees saying that he had decided to give each of us five laps; the fastest man would drive in the GP.

Van Lennep was jet-lagged and unfamiliar with the track. I got the ride, and Surtees gave me one of the highlights of my career.

by Sam Posey