The Old Gal was on Life Support in 1971

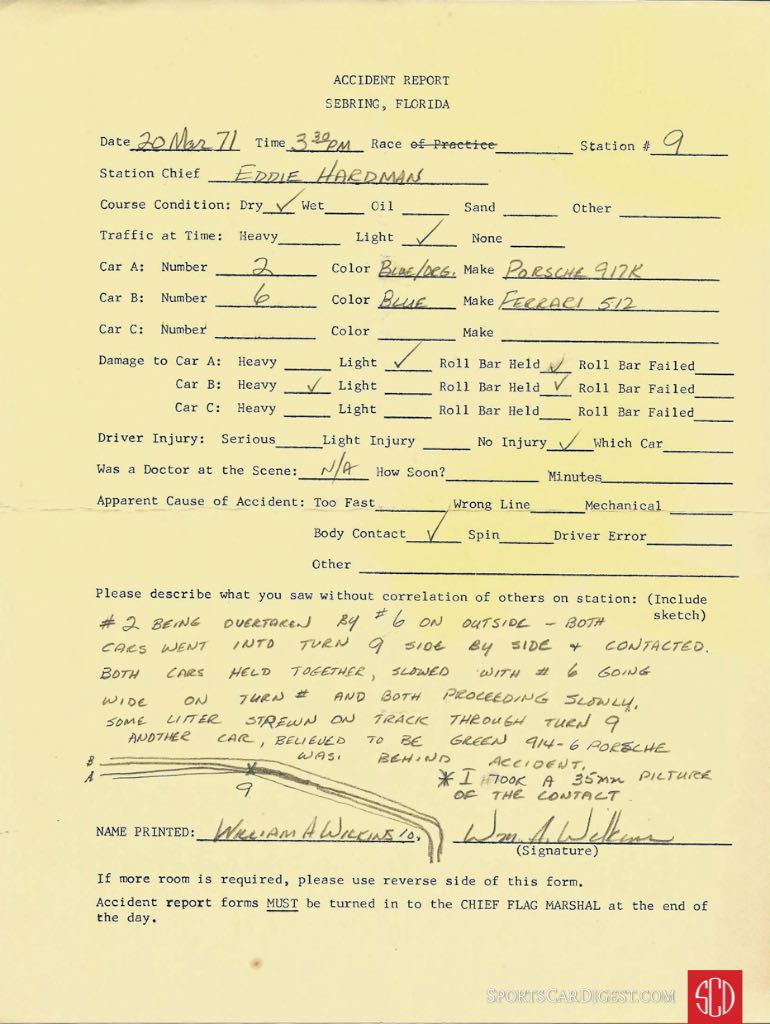

Story by Louis Galanos | Photos as credited

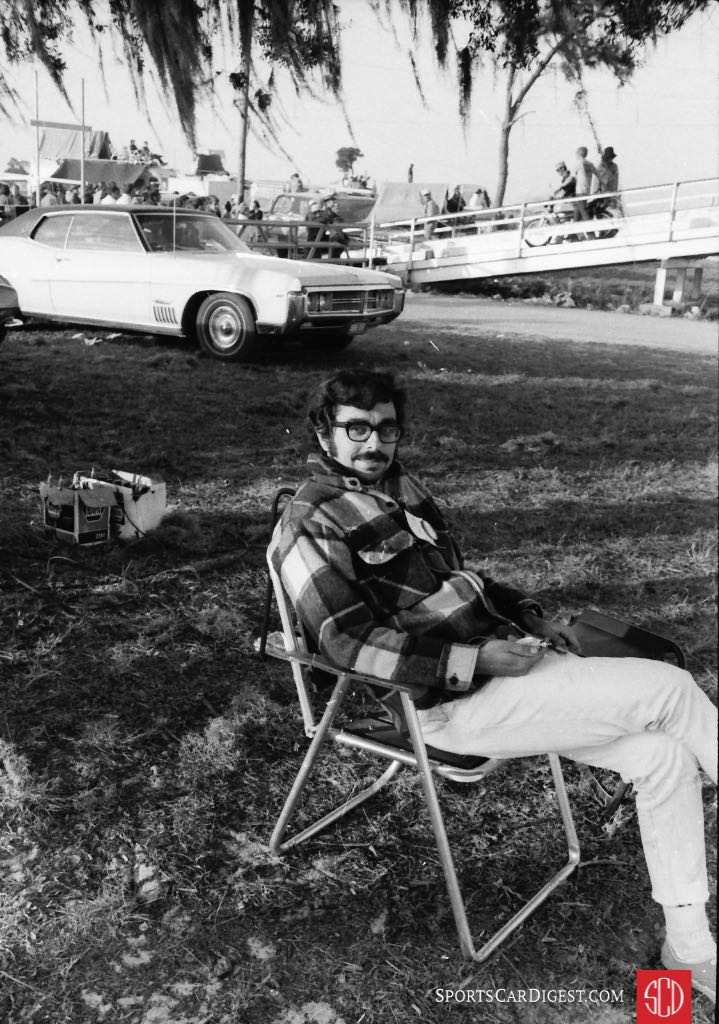

In March of 1971 I was attending the University of Florida on the GI Bill and in our free time my wife and I worked as race officials for Central Florida Region of Sports Car Club of America (CFR/SCCA). The region was blessed with providing race officials for both the Daytona 24 Hours as well as the 12 Hours of Sebring.

In 1970 we had officiated at what many today agree was one of the best if not the best Sebring 12 Hour Grand Prix races ever run. We were looking forward to the ’71 race although with a little apprehension and foreboding.

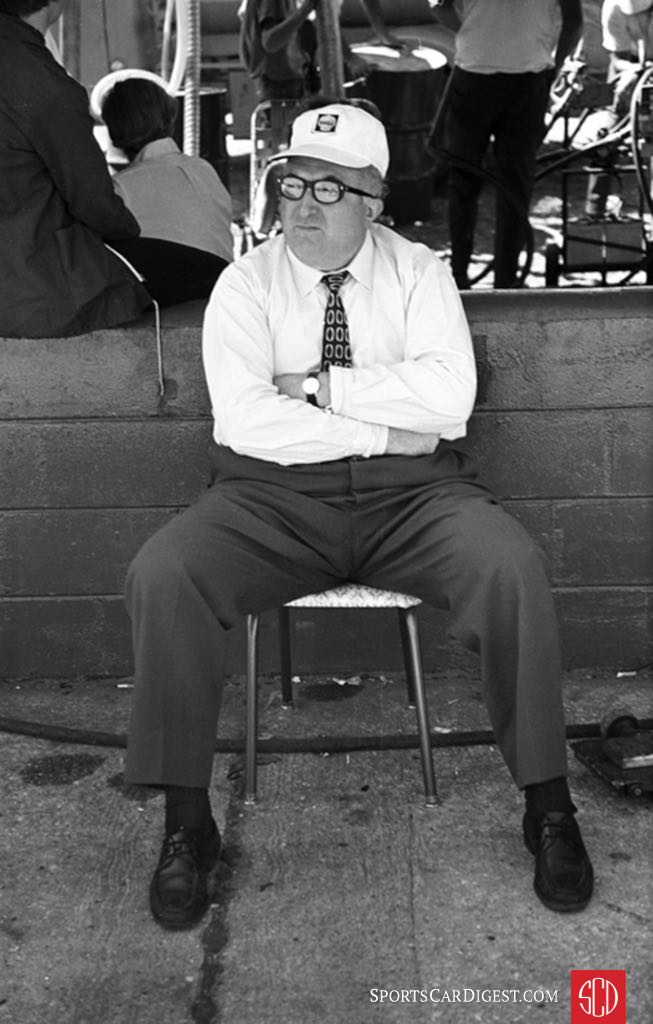

It was common knowledge among veteran race officials that the Sebring facility, with its storied 5.2-mile circuit, was on borrowed time. The international sanctioning body for motorsports (Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile or FIA) had repeatedly warned Sebring race founder and promoter, Alec Ulmann, that unless improvements were made to the track, pits, paddock and spectator accommodations that they would decline to sanction any future events at the facility. This loss of sanctioning would effectively kill the race as an international event and seriously undermine the ability of the track to survive.

Even the most die-hard supporter of the Sebring race would readily admit that the “Old Gal” was showing her age and the facility and environs were long overdue for a major overhaul and it was looking more and more like that was not going to happen.

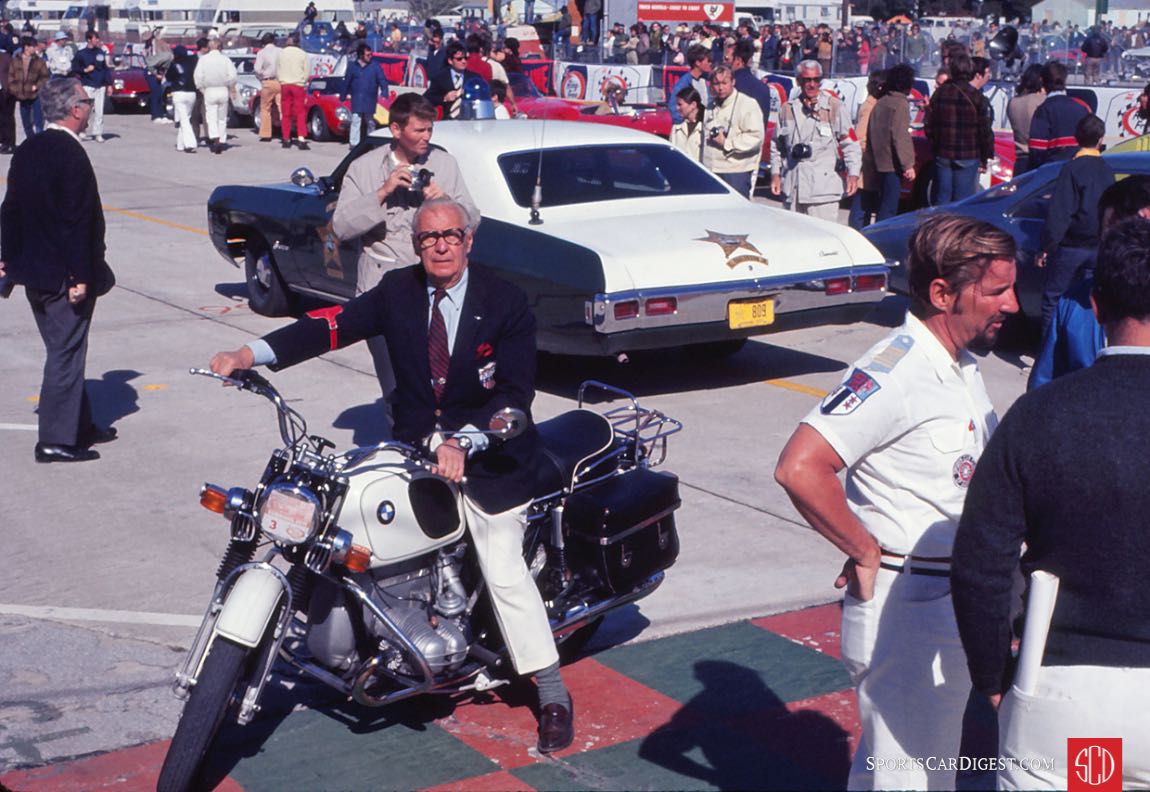

For those who were there early in race week you just might have seen Alec Ulmann, in his blue blazer, riding around on his BMW motorcycle or talking to folks in the pit area. He was conversant in four languages and greeted a variety of people in those languages and fielded questions from them. The question of the day, from reporters, drivers and team managers alike, was if this was going to be the last Sebring. His response was always the same, “If local backing doesn’t materialize, I’ll have to make the inevitable decision I hate to make and say that this is the last race in Sebring.”

When Ulmann referred to “local backing” he was talking about the Sebring Airport Authority which held title to the airport and property containing the track. Each year Ulmann leased the property from them to put on the race. He was not about to put up his own money for track improvements or willing to hustle for the funds. He felt that the track owners had the responsibility to maintain the facility and make the necessary improvements.

As if the demands for improvements by the FIA weren’t enough the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) had notified Mr. Ulmann and the track owners that they could no longer shut down the active runways of the Sebring Airport to use as part of the 5.2-mile circuit. The race surface would have to be shortened or an entirely new circuit would have to be built. In 1971 we were afraid that America’s premier sports car race was coming to an end.

As usual we arrived at Sebring early during race week to get a good camping spot but also to get up close and personal with the drivers and cars without the hassle of what was expected to be a record crowd of race fans. As we wandered through the pits and paddock we noticed a hand-made placard on the wall of one of the pits that said in Italian, “In memoria di Ignacio Giunti”, along with a picture of a driver. It was pretty obvious that this was a memorial to Italian factory driver Ignacio Giunti who won Sebring in 1970 and died in an accident at the 1000 km of Buenos Aires two months earlier. He was driving a factory Ferrari 312PB prototype when he plowed into the rear end of Jean-Pierre Beltoise’s Matra 660 who was ilegally pushing his stalled car in the center of the track. Beltoise was not hurt but the impact with the Matra and subsequent fire were fatal to Giunti.

The death of one of Enzo Ferrari’s favorite drivers put a strain on the relationship between the factory Ferrari team and the Matra team. Ostensibly to honor Giunti’s memory there was no factory Ferrari entry at Daytona in ’71. There was also no Matra factory team there either with word coming through sources that Matra decided to skip Daytona and Sebring in order to concentrate on Le Mans. Not having Matra at Sebring in ’71 probably saved all of us from a nasty encounter between the Italians and French. Time was needed for the Italians to cool off.

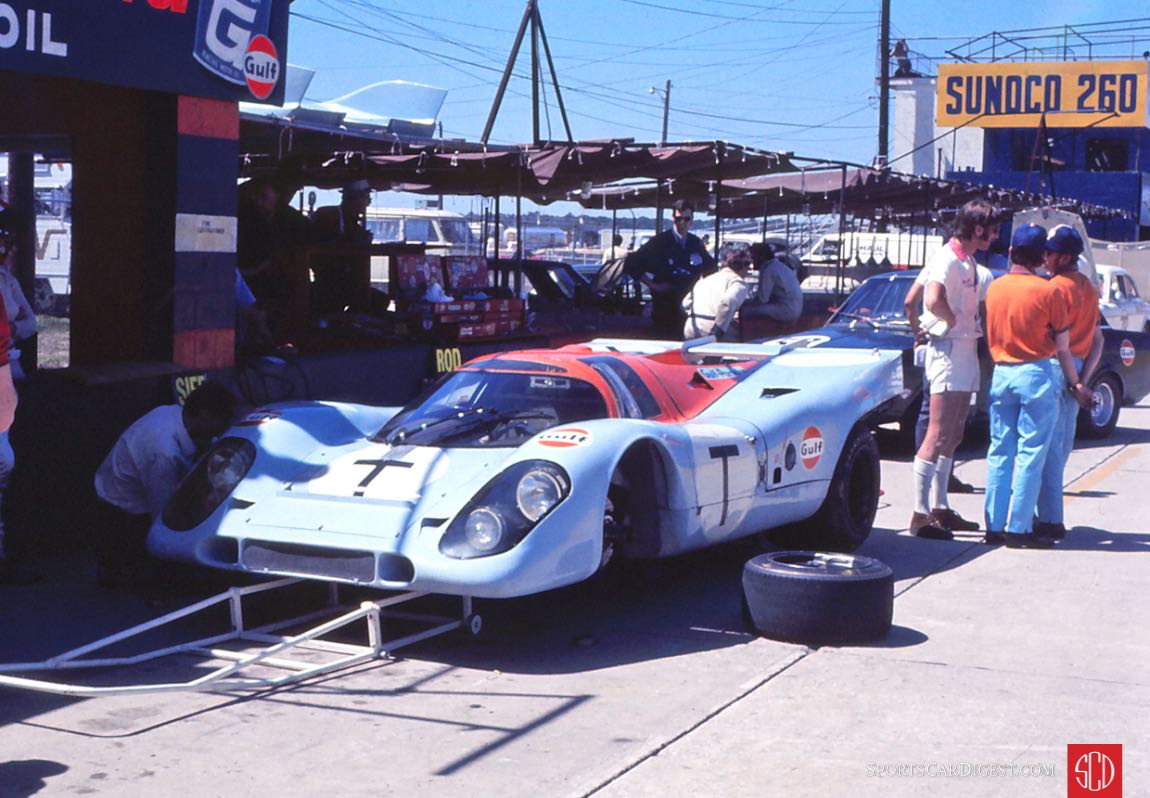

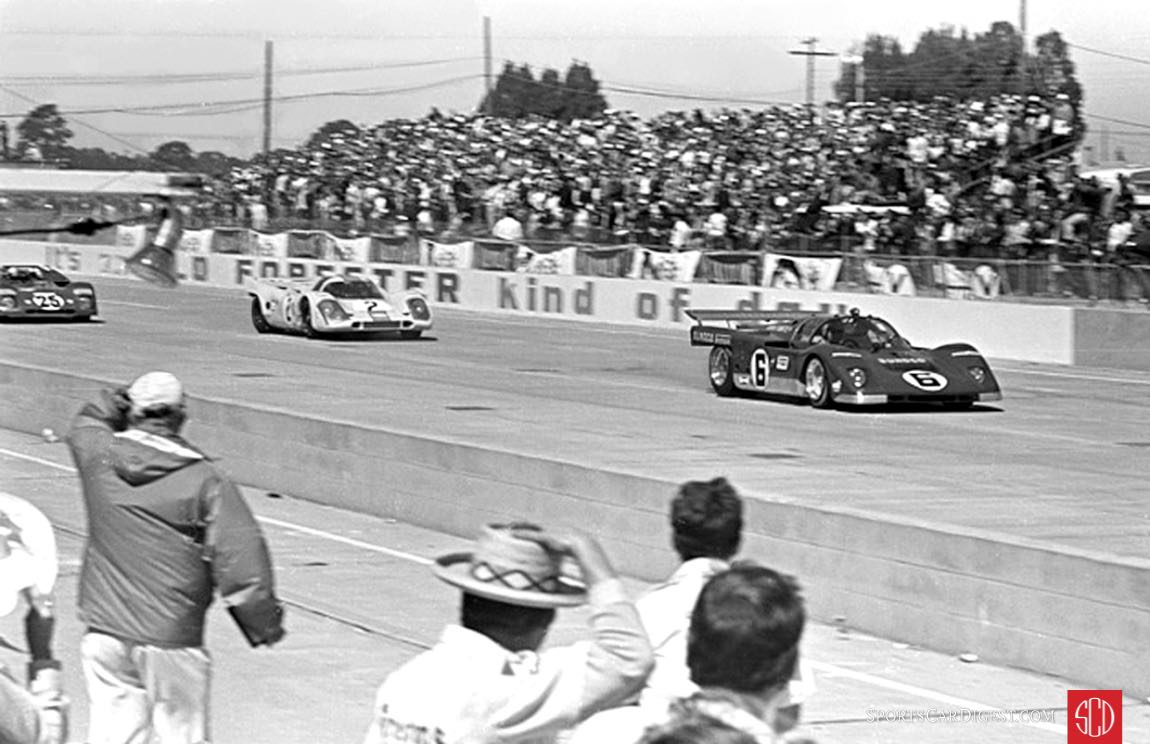

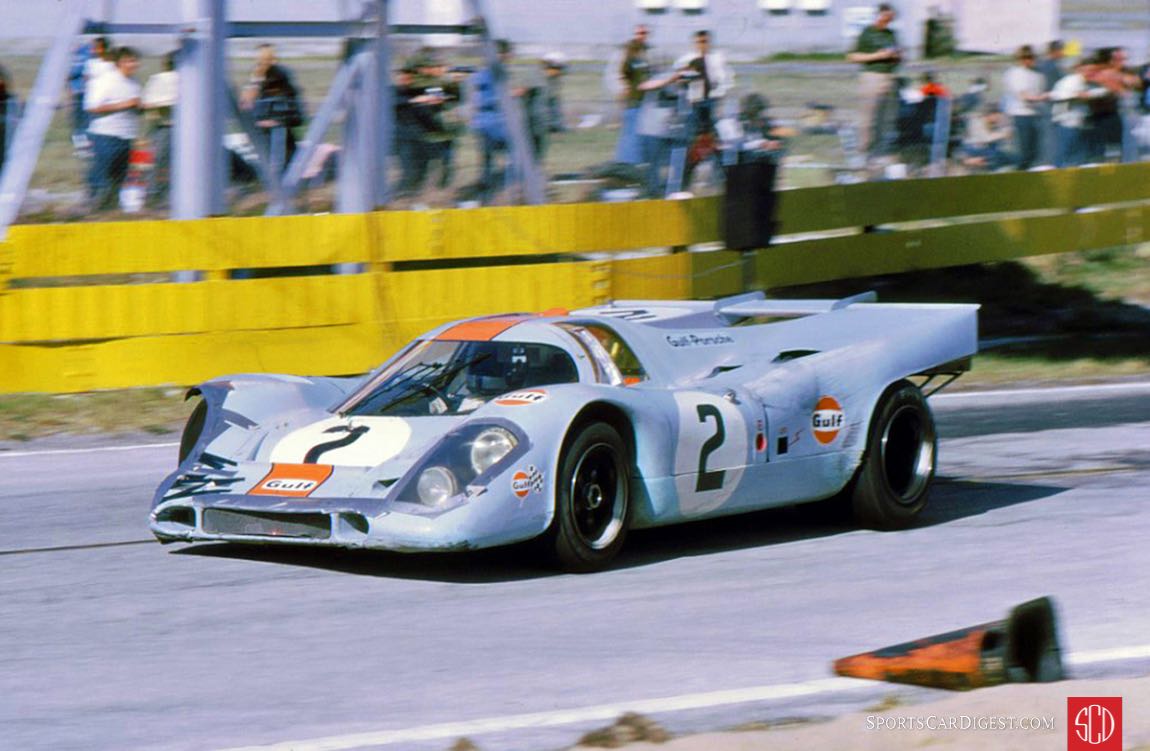

The line-up for Sebring in 1971 promised to be great with a good selection of first-class cars, drivers and teams. If this indeed was the last Sebring it was going to go out with style. Representing factory Porsche and returning to Sebring were two J.W. Automotive Gulf Porsche 917s, plus a spare 917 “T” car. The Gulf/John Wyer Team had won 10 of 12 World Manufacturers races and were favorites to win Sebring.

Another Porsche factory supported car was a 917K entered jointly by Porsche/Audi of Austria and Martini & Rossi Racing of Saarbrücken. Martini had planned to have two 917s at Sebring like they had at Daytona in January but both team 917s were seriously damaged in accidents at that race and all they could bring to Florida in March was one 5-liter car with a 4-speed transmission while the Gulf cars had 5-speeds.

A Gulf Porsche 917 had again won the Daytona 24 in a close finish with a NART Ferrari 512 and some Ferrari fans were hoping for a repeat of the 1970 race when a Ferrari, driven by Mario Andretti, beat Porsche in the closest finish in Sebring history up to that time.

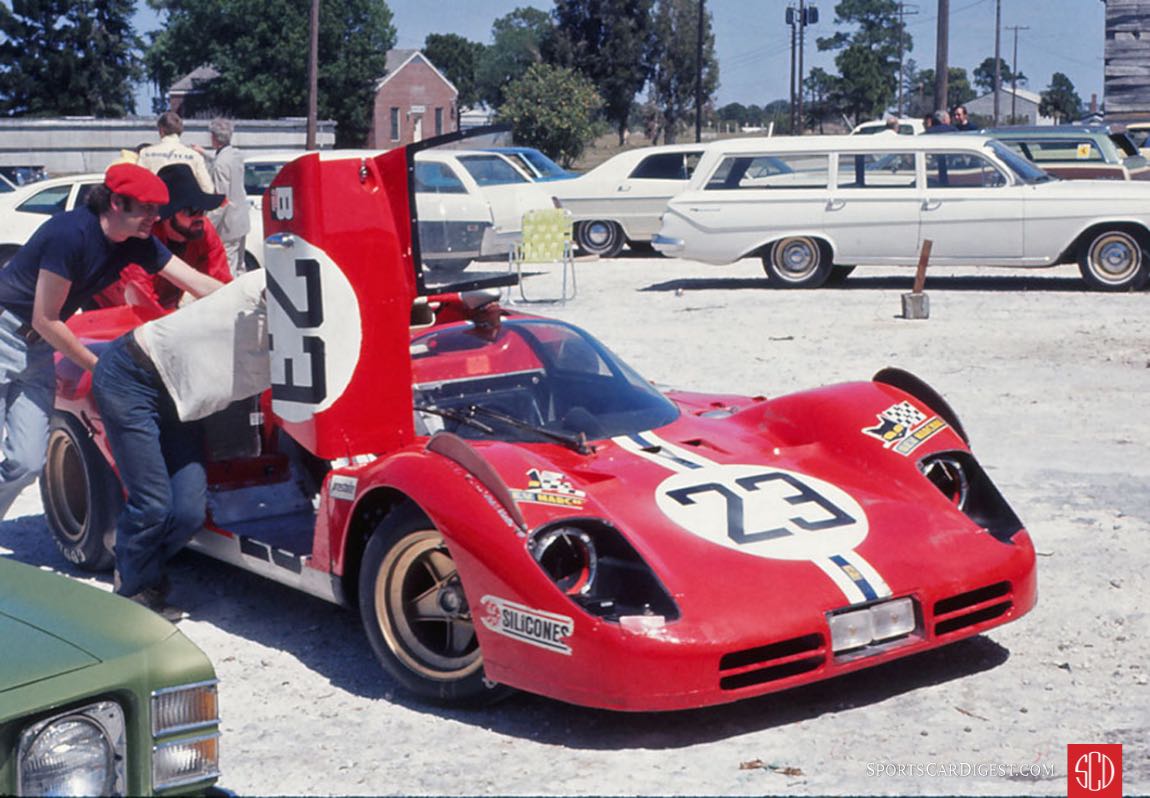

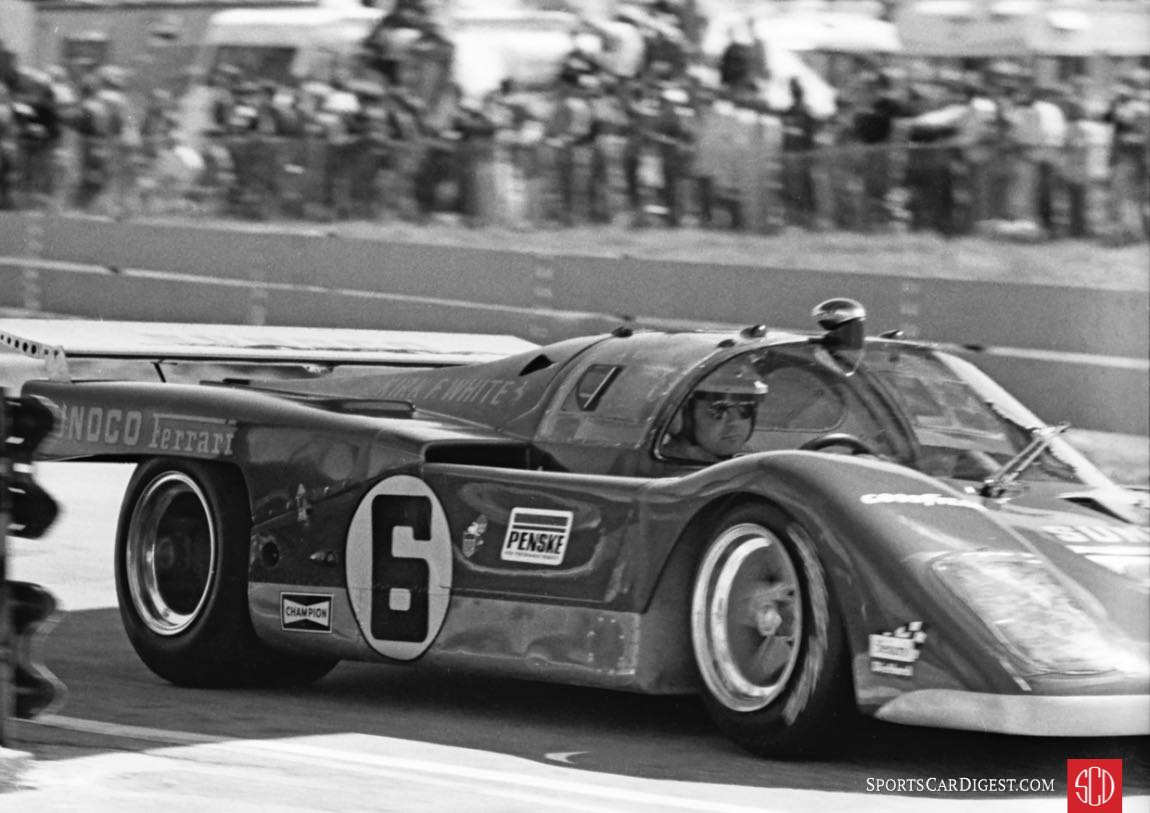

Ferrari would be well represented at Sebring in 1971 with five 512 series Group 5 cars (compared to three 917s) fielded by several independent teams but no factory 512s were entered because Enzo Ferrari had withdrawn all support for the 512. Instead he concentrated his limited resources on perfecting the 3-liter 312 PB racer.

Ferrari’s decision not to support a team of factory 512s was a direct result of the FIA’s decision to outlaw the iconic 5-liter 917 and 512 for the 1972 racing season and mandating an engine size of no more than 3-liters. While Porsche had the resources to support their 917s for one more year Ferrari did not and it was left up to the independents to carry the Ferrari banner in that regard.

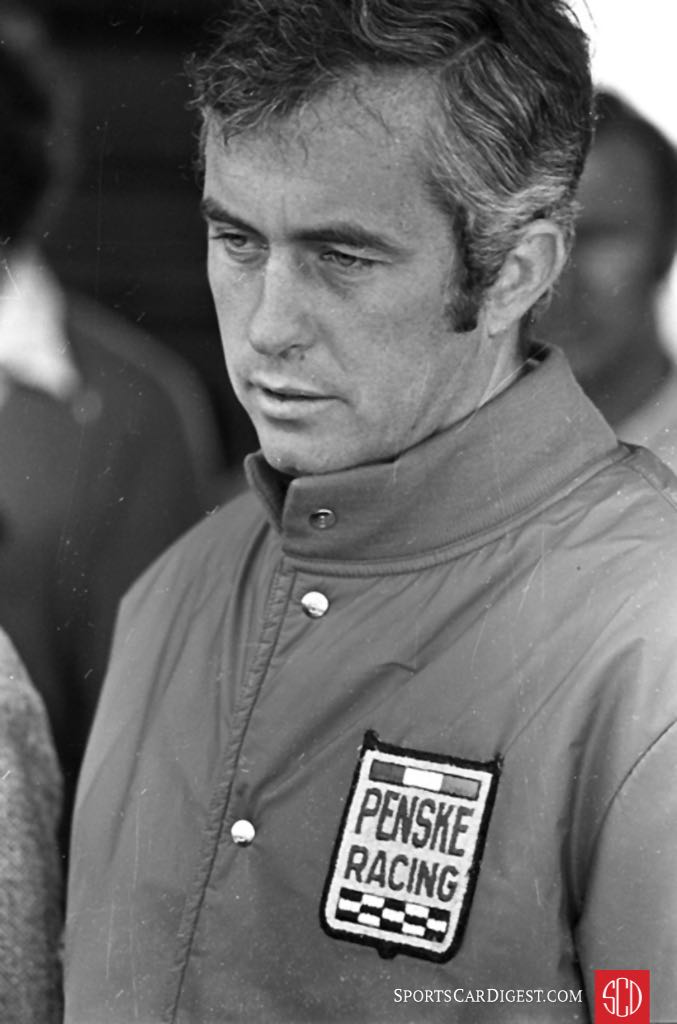

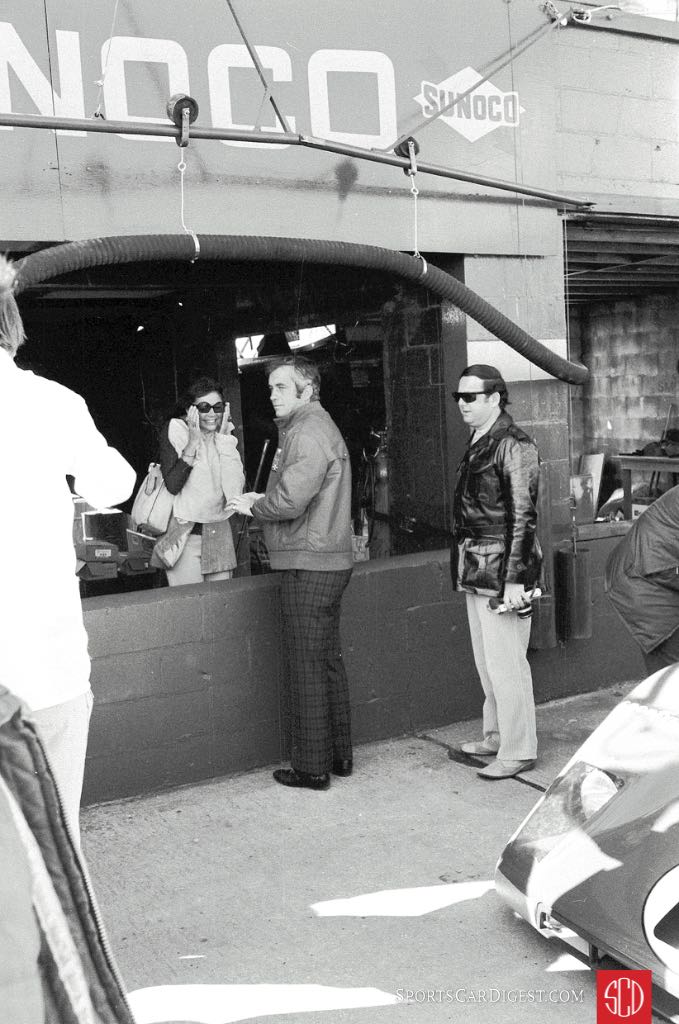

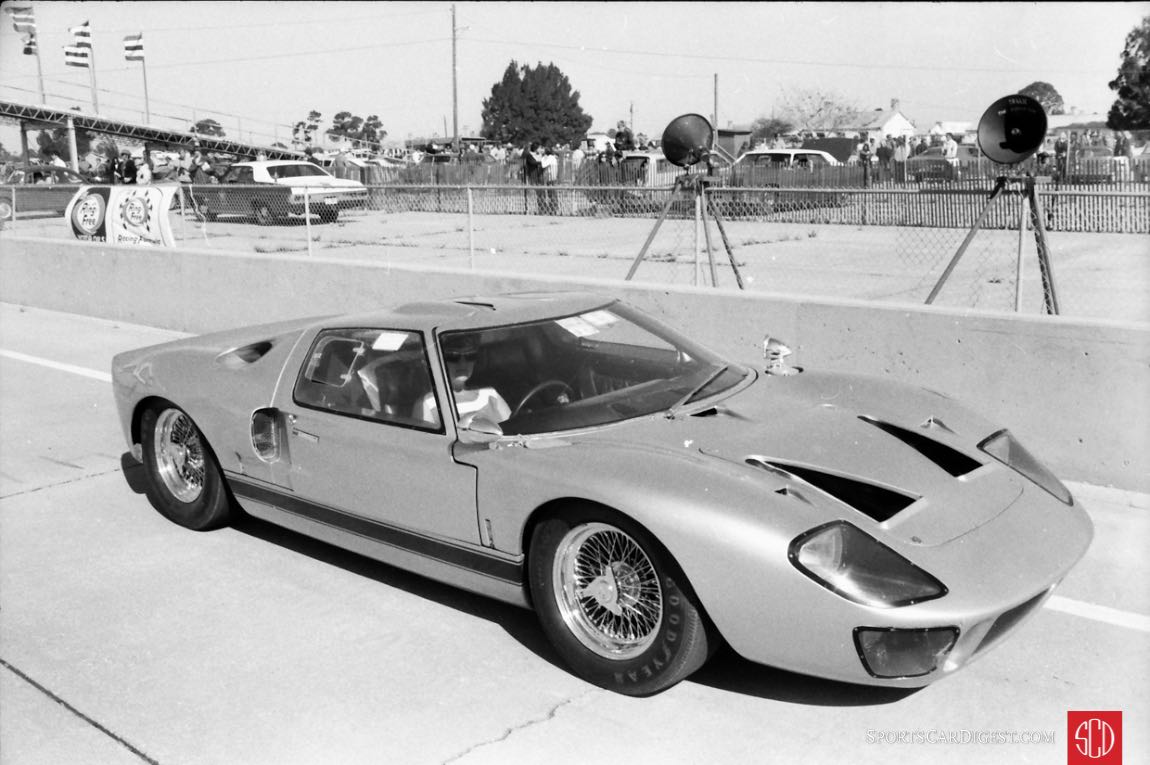

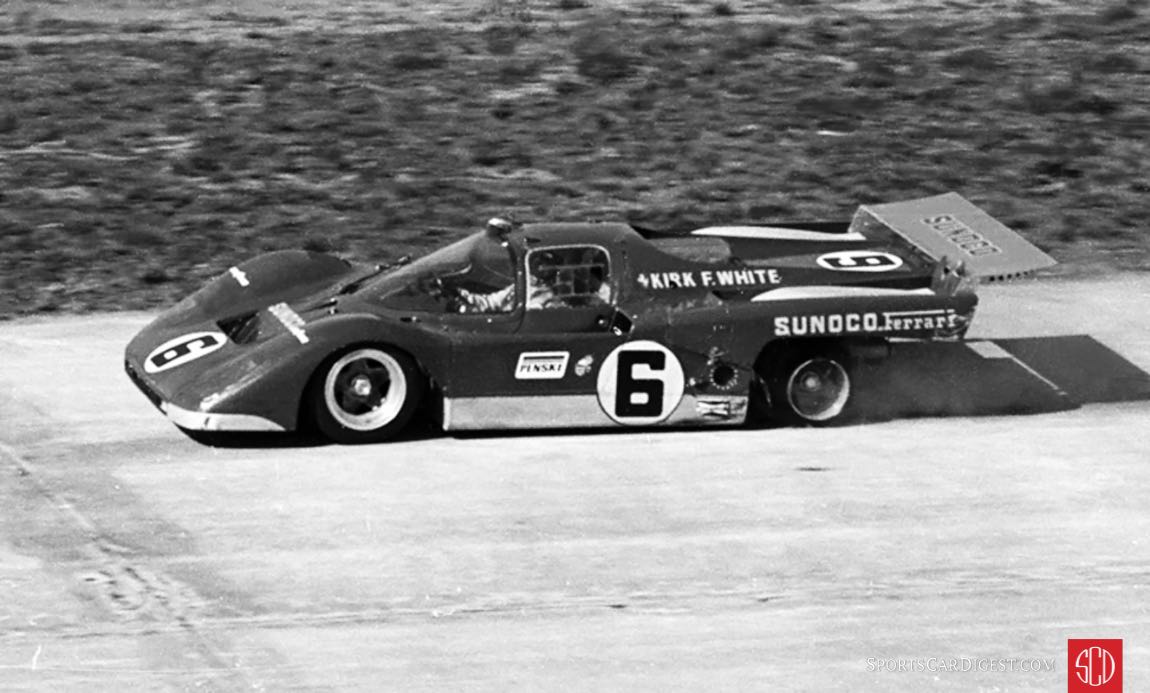

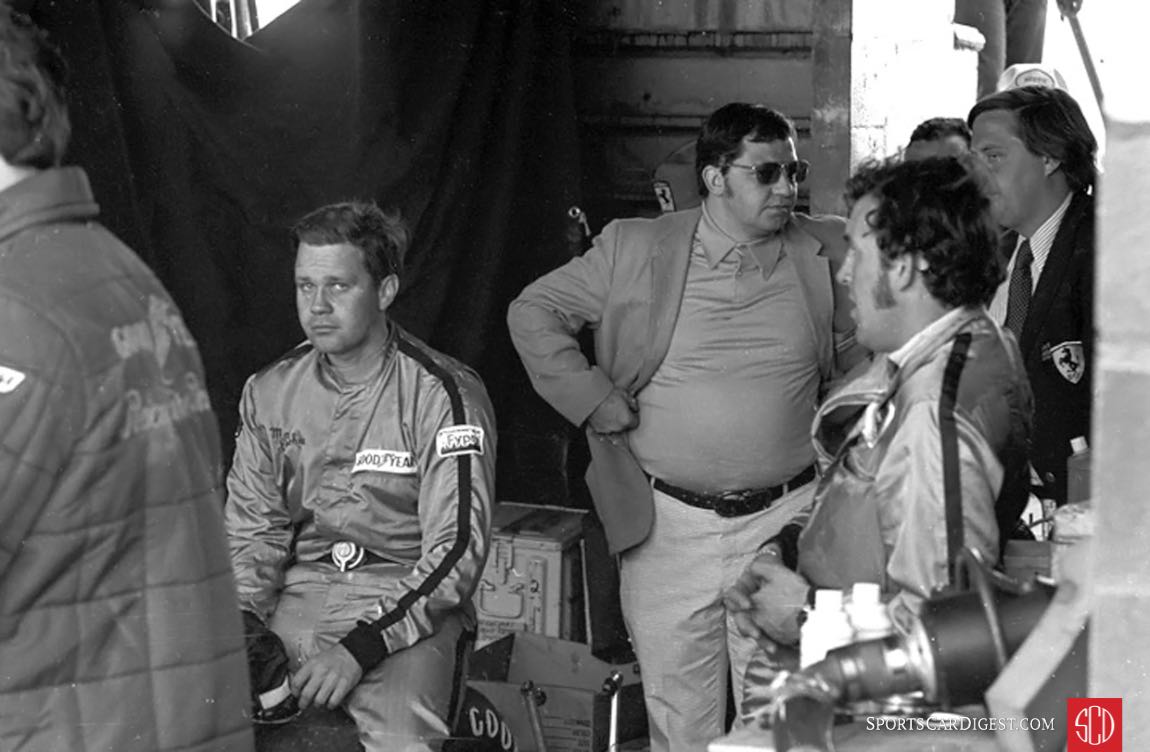

The leading American independent Ferrari team for years had been the North American Racing Team (NART) founded by Luigi Chinetti but in 1971 Roger Penske usurped that title when he took a Ferrari 512S and upgraded it to 512M status and produced what many believed was the most beautiful and best prepared Ferrari car ever entered in a motorsports event.

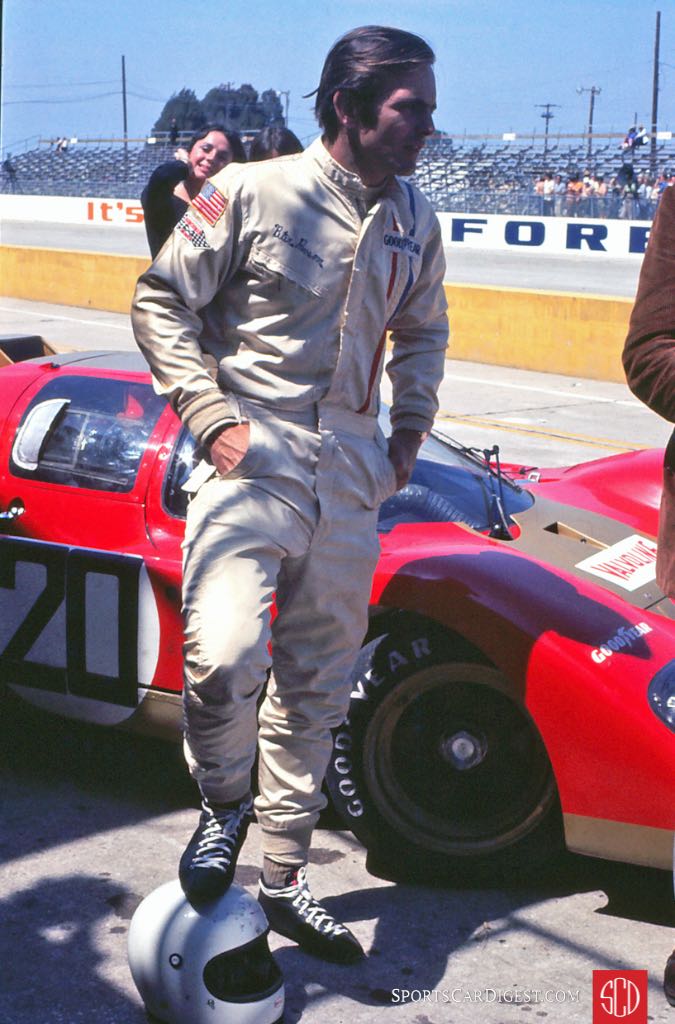

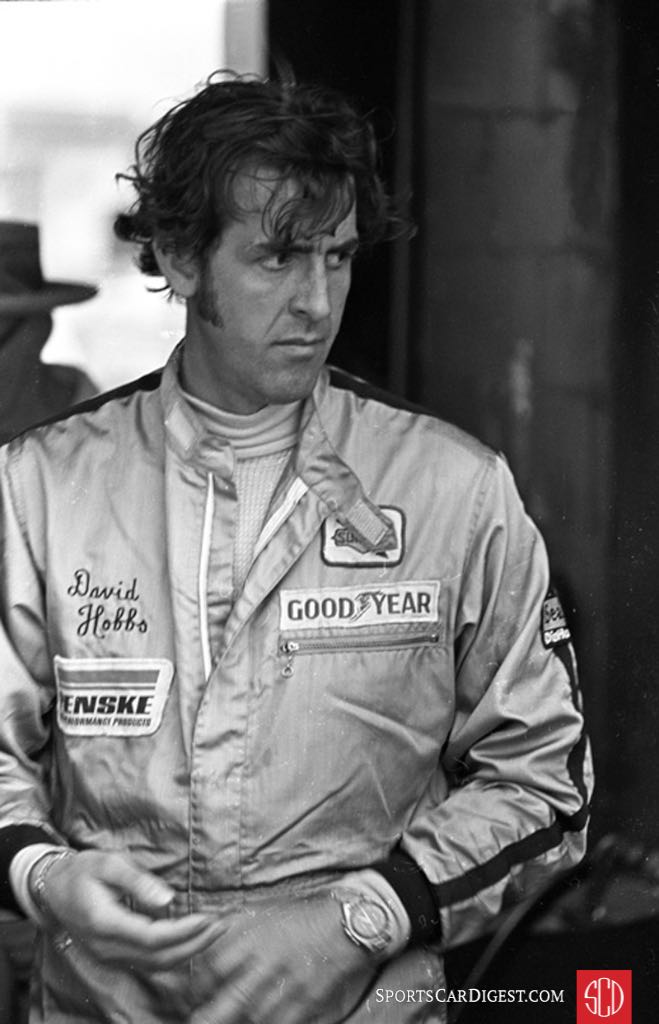

At Daytona in January the Penske prepared 512 M, owned by Kirk F. White and sponsored by Sunoco, captured the pole and proved it was more than a match for the vaunted 917 Porsche. Only an unfortunate accident, resulting in major body and suspension damage, prevented it from winning but it did manage a third-place finish with Mark Donohue and David Hobbs driving. For Sebring, the car was totally rebuilt and Ferrari fans began having dreams of a repeat of Ferrari’s win over Porsche at Sebring in 1970.

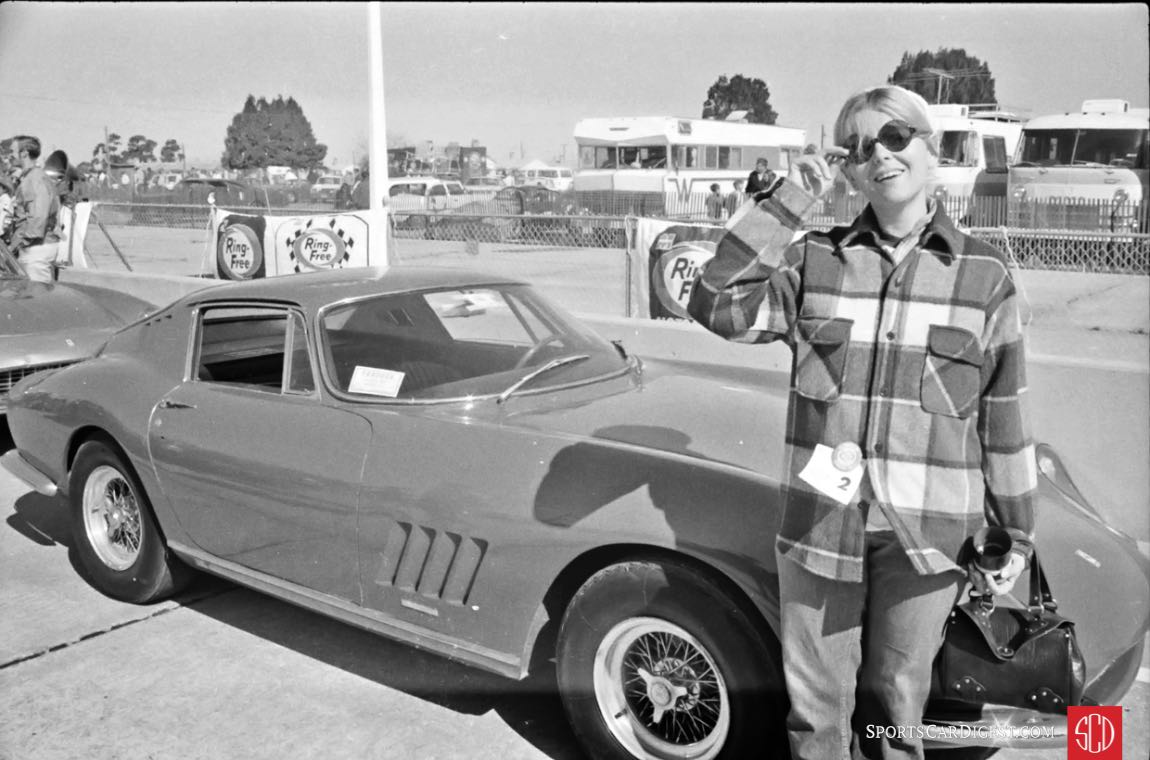

NART had four Group 5 cars entered at Sebring including a 512M driven by Peter Revson and Swede Savage and two 512S’s driven by Sam Posey, Ronnie Bucknum, Chuck Parsons and David Weir. NART also had a 365GTB4 in the race running in the sports class (Group 5) because it didn’t qualify as a GT car. The Corvettes in the race however were considered GT cars. NART also had an older model 312 P entered as a prototype to be driven by Luigi Chinetti, Jr. and George Eaton. The enterprising and talented Chinetti created a new nose and rear deck for the car and it looked very much like the 312 PB being driven by Andretti and Ickx.

The result of having so many entries for NART was that they were woefully understaffed in the pits when it came to mechanics and crew and at times, during the race, Swede Savage and Peter Revson had to change their own tires, gas their car and even do mechanical work on the car. On the grid prior to the race Revson was seen adjusting the rear-view mirror on his car with a borrowed screw driver because his team didn’t have enough tools on hand for him to use. This did not go unnoticed with the motoring press and later stories were critical of NART for failing to be adequately staffed for the race.

Another Ferrari 512M was entered by the Young American Racing Team with drivers Masten Gregory and Gregg Young at the wheel. While the car looked like a 512M it was powered by a 512S engine. One motorsports wag wrote that the Young American team was bankrolled by Young’s wealthy mother. For Young it was only his second year in big-time endurance racing.

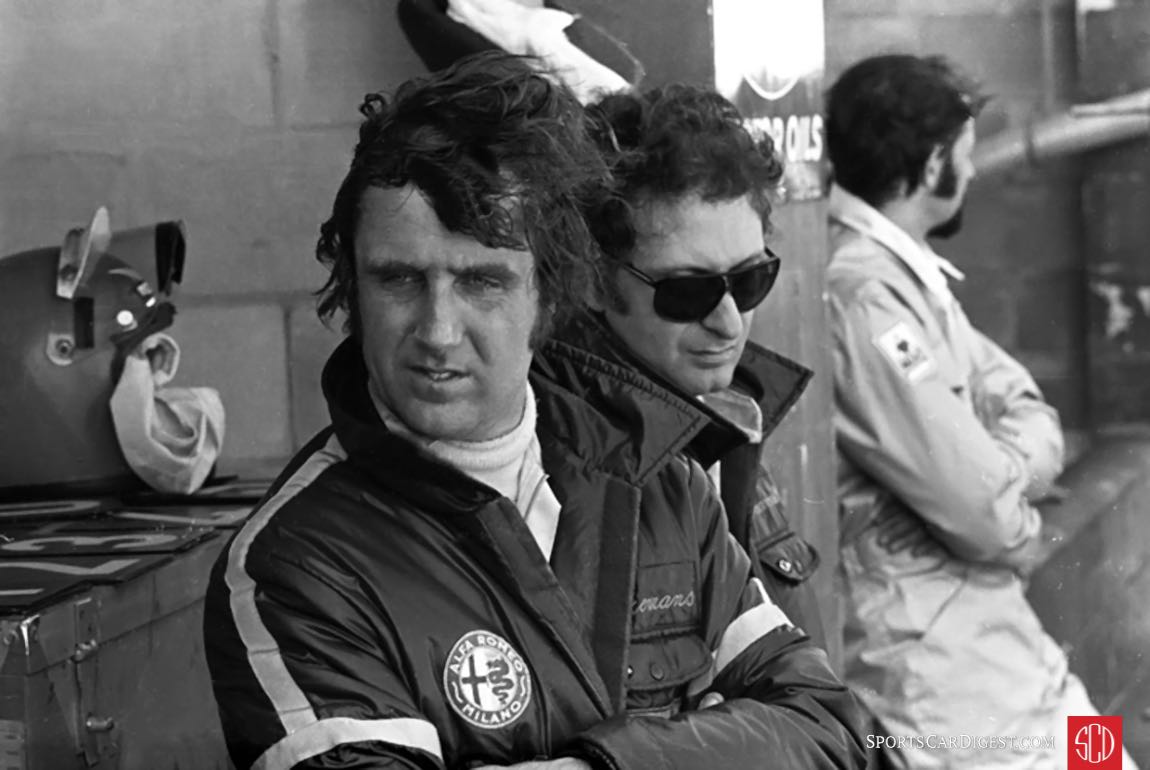

The only factory entered Ferrari in the race was a 3-liter 312P in Group 6 and driven by Mario Andretti and Jacky Ickx. Also in the same group with the Ferrari were three identical 3-liter factory Alfa Romeo T33/3’s with drivers Nanni Galli, Rolf Stommelen, Nino Vaccarella, Tone Hezemans, Andrea de Adamich and Henri Pescarolo.

Qualifying times showed how fast the Ferrari cars were with Donohue, in his 5-liter 512M, turning in the fastest time but Mario Andretti was very close behind (by about a second) in his 3-liter 312 P. The best the 917 Porsches could do was third and fourth on the grid with times several seconds slower than Donohue and Andretti and fifth on the grid was the 3-liter Alfa T33/3 of Galli and Stommelen. With two 3-liter cars in the top five on the grid it was apparent that lighter weight and better agility were more than a match for the big 917s and 512s but could they survive the very rough Sebring circuit and what some called “The 12-Hour Grind.”

To many Donohue’s qualifying time was extraordinary because he drove with a heavily bandaged ankle that some thought might be broken. The injury occurred several days earlier when he was helping load the car for the race and accidentally stepped into a drain near the Penske shop in Newton Square, Pennsylvania.

With Donohue limping around on a swollen and very painful ankle his ability to drive at Sebring was in doubt. That is when Roger Penske took over and decided that if Donohue couldn’t drive then he would. Calls were immediately made to the national HQ of Sports Car Club of America to see about renewing Penske’s national and FIA license which had expired seven years earlier when he retired from racing.

Several licensing rules were waived and the SCCA justified it based on Penske’s long and illustrious driving record before he retired. Just to cover their butts the SCCA told Penske that he would be observed by stewards during practice at Sebring and if they felt he did not have what it took to drive they would remove him.

As it turned out Donohue’s ankle was not broken and he even drove the transporter all the way from Pennsylvania to Sebring having only to stop twice for mechanical issues with the transporter.

To make sure that the sprained ankle didn’t get any worse during the race Penske talked to Alec Ulmann and Ulmann arranged to have Miami Dolphins trainer Bob Lundy check Donohue out and properly wrap the ankle. Lundy was working in the track hospital trailer during the race and every time Donohue turned over the car to co-driver David Hobbs Lundy would come over to the pits to see how Donohue was doing and tend to him if needed. You must wonder if Lundy would have done the same for one of the drivers who drove an MGB in the race?

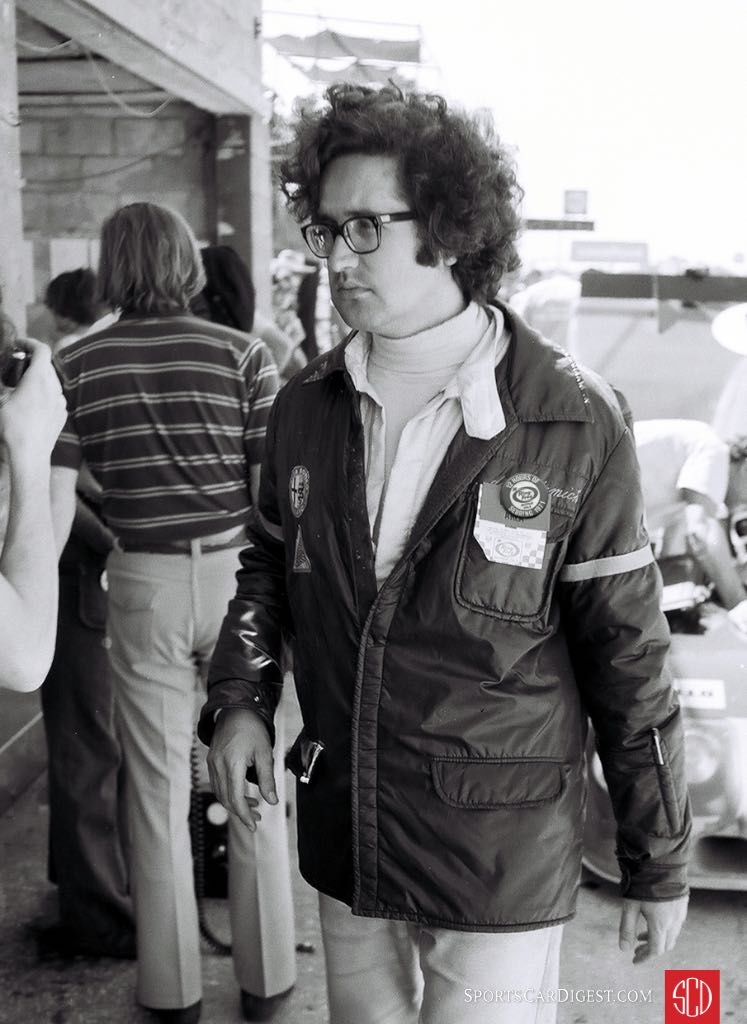

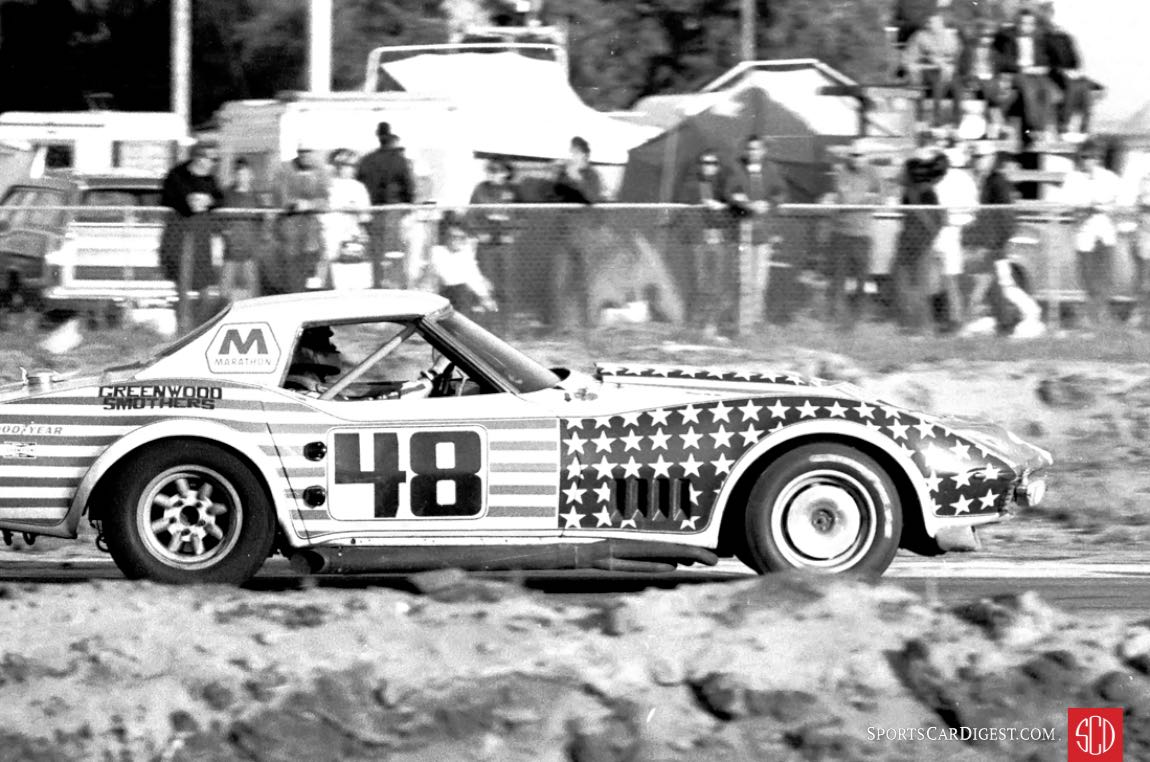

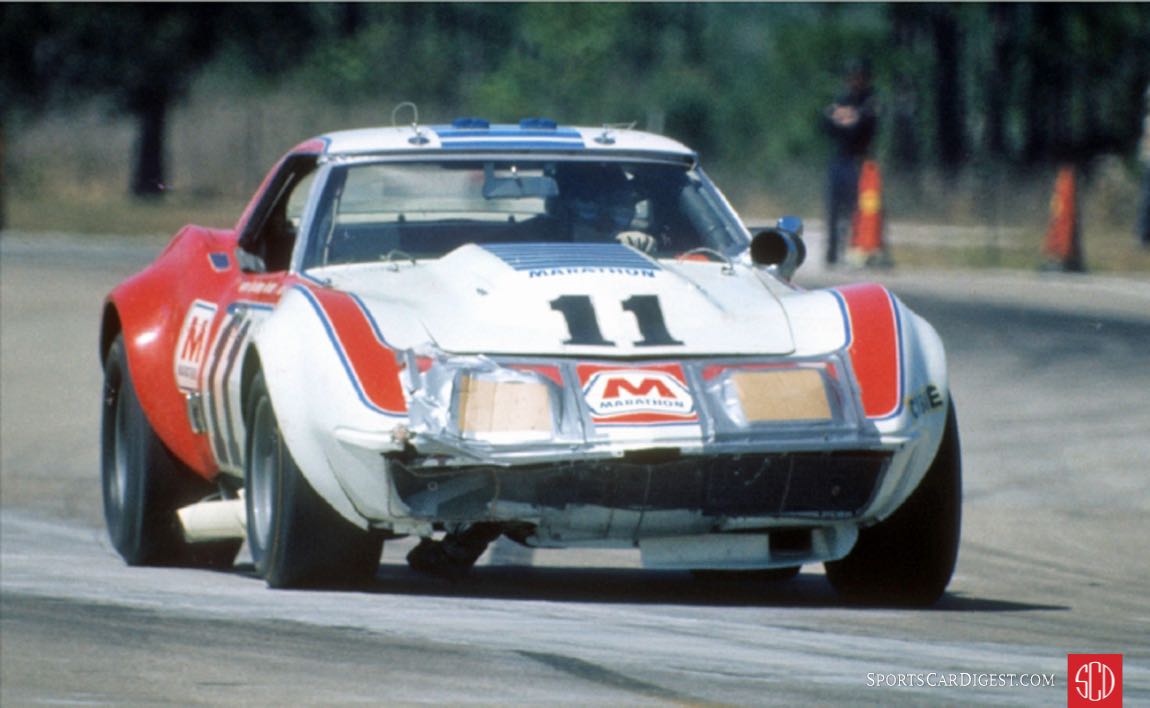

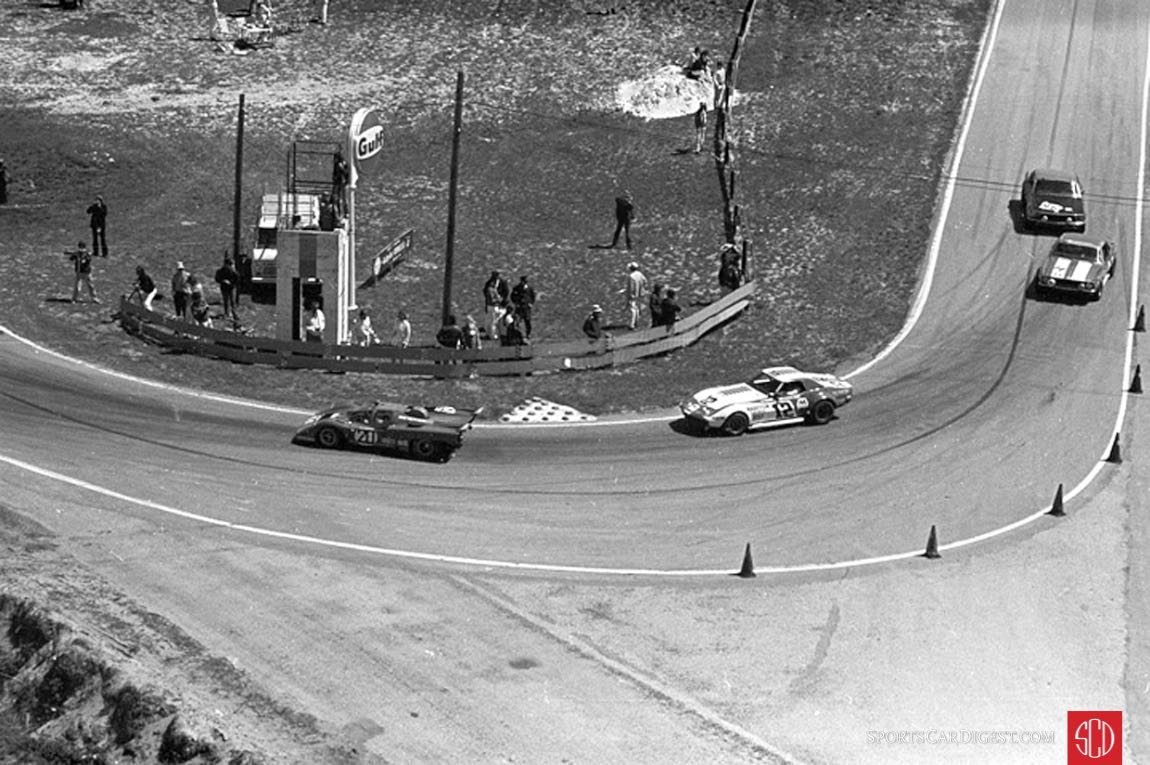

Also on the grid, with all that exotic machinery (Ferraris, Alfas, Porsches), was enough American iron to make any American racing fan happy. A half dozen Corvettes were among the top 25 qualifiers and in that group, was legendary Corvette driver John Greenwood who would share driving duties with TV personality Dick Smothers. Within two years Greenwood would be referred to as “The Sebring Angel” because he literally would save the Sebring race from the trash heap of history.

Just ahead of the Greenwood Corvette, in 14th position on the grid, was the 7-liter Vette of Don Yenko, Tony DeLorenzo and Jerry Thompson. Like Greenwood all three of these men would eventually become legends in Corvette racing. There were four other Corvettes on the grid and all six were among the top 25 qualifiers.

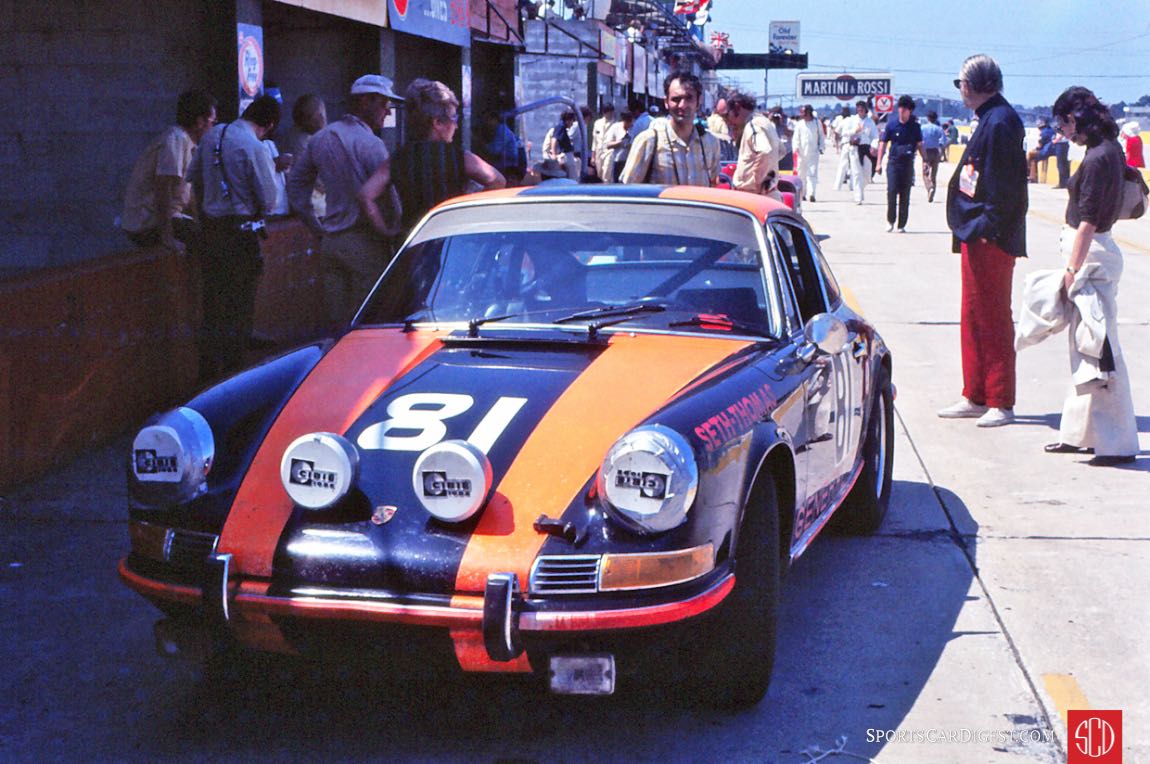

Production Porsches would outnumber all other street cars with six 911’s, four 914’s and three 906’s entered. One of the Porsches would be driven by Apollo 12 astronaut Pete Conrad. Co-driving with Conrad was John Buffum and Steve Behr in the Meany prepared 914/6. Those 13 production Porsches were almost matched by the 12 Camaros entered in the race. Sadly, for Ford fans, there were only two Mustangs at Sebring and one Shelby GT500. All three would fail to finish. For British race fans, there were two MGB’s but neither was running at the end to take the checkered flag.

All total there were 57 cars sitting on the starting grid ready for the rolling start that was scheduled for 11:00 am on Saturday. There was also a record crowd of more than 50,000 race fans with many coming to see what they thought was their last Sebring. The Le Mans style start that was so much a part of Sebring for decades was eliminated in 1970 due to the mandates of the FIA, ostensibly for safety reasons. More than one steward said to me that Sebring has never had a major accident associated with the Le Mans style start where drivers sprint across the track, jump in and then see who would be the first under the Mercedes – Benz Bridge. Admittedly many of those who were first under the bridge never bothered to buckle their seat belts but all did by lap two.

The FIA never issued clear guidelines for 1970 as to what kind of start was appropriate and up to three hours before the 1970 Sebring race the officials were considering a modified Le Mans style start where a driver would sprint across the track to their car in which their co-driver was already buckled in. Only when the sprinting driver could touch the car did the co-driver start the engine and pull out onto the racing surface. This created a nightmare image in the minds of some stewards of a much quicker driver getting to his car ahead of some slower drivers and when the co-driver blasted out of the grid box he might encounter a slower sprinter. Race fans might get a laugh at the sight of a race car with a driver holding onto the hood for dear life as the car careened through turns one and two. Fortunately for everyone, the stewards settled on a rolling start which today is commonplace in most motorsports events.

While the stewards at Sebring in 1970 had to deal with how to start the race the officials in 1971 were faced with the very thorny issue of how many cars would be allowed on the grid for the 11:00 a.m. start.

For years the cars had been getting faster and faster and the disparity in speed between the fastest and slowest on tracks like Daytona and Sebring began to grow. Thus, drivers of some of the fastest cars frequently complained about the slower cars blocking their way and creating dangerous conditions on the track. This situation between faster and slower cars was graphically apparent at the ’71 Daytona 24 where the closing speeds, on the 31 degree high banks, between the fastest and slowest cars often exceeded 100 mph.

To mollify some big-name drivers and teams, and ostensibly in the name of safety, the FIA came up with what they called the 130 percent rule that was supposed to address the issue of slow cars creating a hazard on the track. Under this rule if a car failed to set a lap speed within 130 percent of the fastest time in qualifying then it would not be allowed to start the race.

Daytona race officials in 1971 strictly adhered to the 130 percent rule by cutting the starting grid from 65 cars to 48. This was done even though those drivers who were cut had paid their entry fee, practiced, were told they had qualified and were given a grid position. The decision to reduce the field in accordance with the 130 percent rule was done shortly before the start of the race. No idea if the entrants who were eliminated got their entry fees back.

Not long before the running of the Sebring race Penske had rented the track for testing the newly rebuilt Penske/White Sunoco 512M that had been badly damaged in the Daytona 24. Donohue produced some blistering speeds breaking the previous record set by Mario Andretti by several seconds despite testing on a wet track. This worried Ulmann and other track officials who were aware of what happened at Daytona under the 130 percent rule. They did some quick calculations and determined as many as 20 to 25 cars already entered just might not make the grid under the 130 percent rule. This would seriously diminish the starting grid to just over thirty cars which would not look very good in the eyes of racing fans and the motorsports press. Ulmann contacted friends at the FIA to discuss the problem and they granted a “special dispensation” to use 140 percent instead of 130. They shouldn’t have worried because actual qualifying times were much slower than what Donohue did in testing and few entrants would have been sent home under the 130 percent rule.

After a brief storm with tornado warnings the night before race day dawned with perfect weather and the 57 cars scheduled to start the race were pushed to the starting grid as the usual fanfare, marching bands and hoopla swirled around the grid. Some teams had worked long into the night to get their cars ready and it was a curious sight to see mechanics literally working on the cars until the grid stewards began to clear the grid. Eventually, after many requests from the public-address system, the starting grid was cleared and drivers strapped themselves in for the pace lap and rolling start.

For corner marshals this was a magical time because you could get very close to the track and wave to the drivers as they came through your turn on the pace lap. In some areas of the spectator paddock race fans would jump the retaining fence and run right up to the track to cheer on their favorite driver or car. More than one young lady was seen to lift her top and flash the drivers as they went by. It was a credit to the drivers that they didn’t lose concentration and run into the back of another car or run over some of the fans. It would take a minute or two to get these race fans back over the fence before the green flag fell.

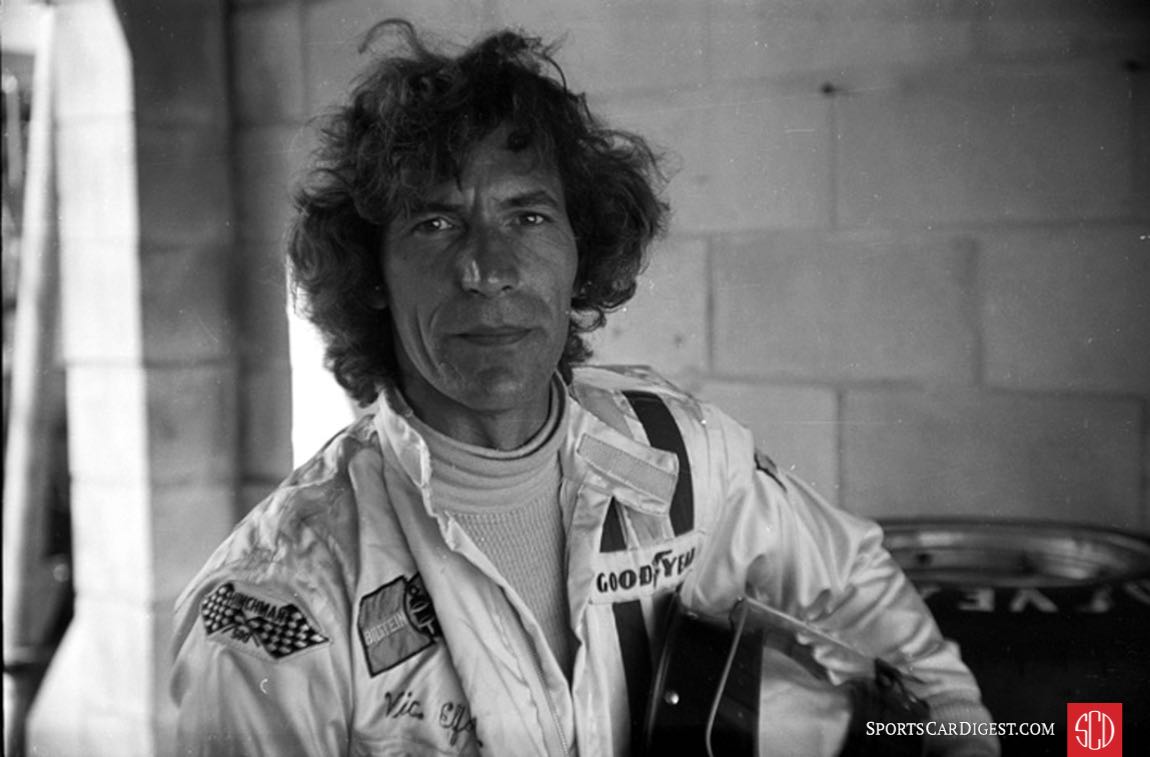

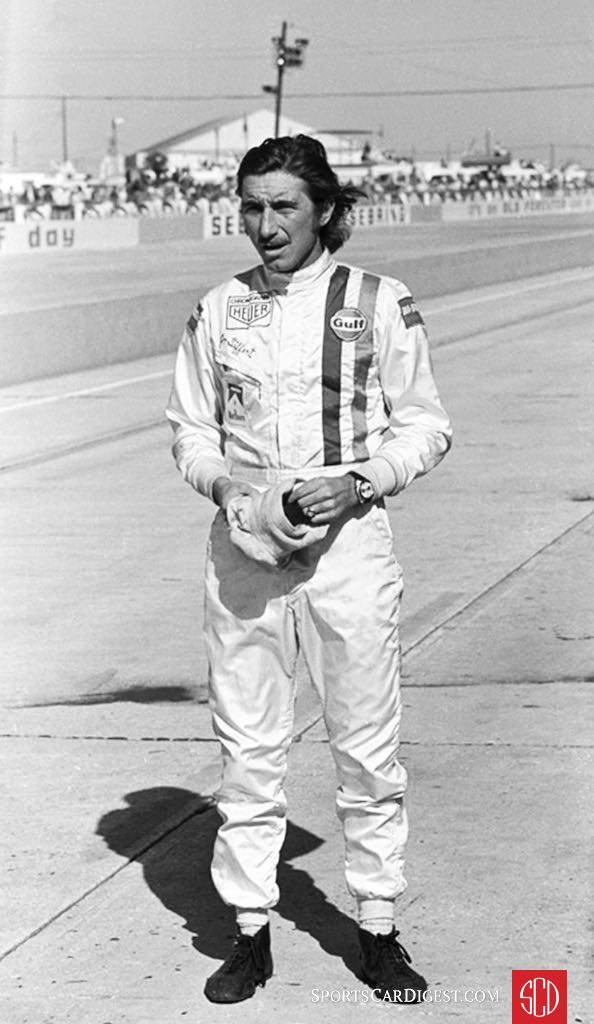

Even from the farthest reaches of the track you could tell by the roar of engines when the green flag fell for the start of the race which occurred on time at 11:00 a.m. Leading a group of Porsches and Ferraris around the 5.2-mile circuit was the Ferrari 512M of Mark Donohue. He would continue to lead until his first pit stop at the end of 20 laps. At that point Jo Siffert would take over the lead and produce the quickest lap of the race at 124.418 mph.

As expected, in those early laps, there would be some retirements and the first to go behind pit wall was the Chevron B-16 Ford of Janet Guthrie. The record books indicate that the car retired with a blown head gasket after completing only one lap. Those official results rarely tell the whole story of what happened so I contacted Ms. Guthrie at Janet Guthrie Racing and asked her to explain why she and her co-drivers (all female) became the first to retire in ’71. She kindly consented to email me an answer and it is as follows:

“In 1970, Ring-Free Oil had finally engaged a competent contractor, and our women’s team won the Under 2 Liter Prototype category. As usual, the men driving for the team had a better car: but in 1971 we arrived at Sebring with the promise of a Cosworth-engined Chevron B-16, similar to the one the men had driven the previous year. However, one of the Cosworth Chevrons didn’t show up, and we women were (naturally) assigned the slowest car, which had a BMW engine. One of my co-drivers over-revved it in practice by at least 1500 rpm (the tachometer was pegged), and it swallowed a valve.

Owing to the terms of the Ring-Free contract, I then got three laps of practice in the Cosworth-engined car that was originally supposed to be ours. It was a beauty! I found delight that I could get through the turns as fast as the fastest cars entered, although the engine displacement was much smaller. If the other car couldn’t be repaired; I would start in this one. I lusted after it.

Minutes before the race, I was getting into the Cosworth when a mechanic came hustling up. At the last moment, they had found a BMW engine in a junkyard, and I was forced back to the car. The junkyard engine didn’t last long.

Curious about an odd handling issue, I looked under the hood. The bolts securing some major suspension pieces were loose, about to fall off, and had the engine lasted just a little longer, the outcome would likely have been disastrous. So, I guess you could say that the engine failure was good news.”

Five laps later the Camaro driven by John Cordts retired with a blown differential and following them, 14 laps later, was the NART Ferrari 512 of Chuck Parsons. Parsons was coming into the Hairpin Turn when the throttle on his car stuck open. He slammed heavily into the sand bank, which stood almost eight feet high, and the impact tore away the front oil coolers leading to a retirement.

Now you might assume that the loss of this car would sadden and depress some in the NART camp. However, with the loss of that car it made it immeasurably easier for the short-staffed pit crew and mechanics (only two) to maintain the other NART entries during the race.

Michael Keyser and Bruce Jennings bit the dust on lap 23 when their Toad Hall Racing Porsche 911S expired. I communicated with Keyser about his remembrances of the race and he responded with this:

“I don’t remember much about the race. I do remember we stayed at a motel on the right side of Route 27 headed south and right across from Lake Jackson.

It was my first time driving at Sebring and I was surprised how rough it was. At night practice I followed a car ahead of me who had gone off the circuit, thinking he knew where he was going…wrong. In the same practice, coming out of the Green Park Chicane, I guess I held up Jacky Ickx in the Ferrari 312P because he pulled alongside and slowed and shook his fist. A few years later when I got to know him I “reminded” him about that. “Who? Me??? I’d never do anything like that.” Right.

I started the race and on the first lap I had so much adrenaline pumping that my foot was jumping off the accelerator going down one of the runways. I had to hold my leg down with my right hand! I remember fighting with the #29 914/6 and then there was a big bang and I lost power. When I got back to the pits, there was a hole in the block and a lot of oil…and a badly bent titanium rod. End of story.”

Keyser and Jennings were soon followed behind the pit wall by the MGB of Jim Gammon and Dean Donley after their engine died. Before the checkered flag would be waved 22 more cars would suffer mechanical issues and fail to finish.

As the first hour of racing came to an end pit crews all along the front straight started getting ready for the first pit stop for their car. In the Gulf pits they had already determined what the fuel limits were on each car and each driver was told when to bring in the car. As a reminder to drivers a pit crew member was usually sent out to the pit wall to signal the driver with one word, “IN”.

Up in the pit box an observer saw the #1 Siffert 917 coming down the back straight and into turn 12. They shouted to the crew member at the pit wall that Siffert was coming so he could put up the signal which Siffert saw and signaled he had seen it.

The low-fuel light was already on and this worried Siffert but less than a lap awaited him. As luck would have it the car died after entering turn 10. For those of you who remember the old 5.2-mile circuit, turn 10 is the furthest point from the pits and at the tip of the almost mile long North/South runway.

Being out in the middle of nowhere was not lost on Siffert. Initially he decided to hoof it back to the pits for a can of fuel. However, at the last second, he decided to hitch a ride on the motorcycle of a corner marshal so off they went arriving at the paddock/pit area in short order.

This decision by Siffert has been second guessed for years because it was well known by all that, under these circumstances, a driver cannot accept assistance of any kind in getting back to the pits. To do so risked disqualification from the race. This is what happened to Stirling Moss in 1959 for doing the same exact thing. While the stewards didn’t disqualify Siffert they did penalize his car four laps. Added to that were the additional 19 laps lost before he got back to the car, now on foot, then fueling the car and driving it back to the pits for a fill-up. The failure of the stewards to disqualify Siffert did not set well with some Sebring veterans and suggestions of favoritism for big name drivers and teams was raised.

Both during and after the race the motoring press was critical of this “stupid mistake” and blamed Siffert for not pitting before he ran out of gas or blamed the pit crew for miscalculating how many laps could be run before refueling. Siffert’s use of a motorcycle to get back to the pits also came under harsh scrutiny. In the minds of many these actions may have cost the Gulf team the win.

In John Horsman’s 2006 book, Racing In The Rain, John Wyer’s chief engineer for the Gulf 917 team tried to explain what happened. According to him they had determined how many laps could be completed on the Sebring 5.2-mile circuit before they had to bring in the two 917s for refueling. These calculations were a result of their vast experience with both cars.

Siffert was told earlier to bring in his car on lap 26 and to remind him he was also signaled to do just that. Unfortunately, the car ran out of fuel after completing half of lap 26 and at the furthest point on the track from the pits.

After the race it was determined, by fuel consumption figures, that Siffert’s 917 consumed quite a bit more fuel per 100 kilometers than the other 917. Somewhere there had to be a leak so they ran numerous tests on the car and found nothing. They could only conclude that there “…was a fault in the metering unit, as no leaks could be found.”

As the results came in from timing and scoring for the first hour of racing it showed the Siffert/Bell Porsche in first but that would change soon when the four penalty laps were deducted. The Donohue/Hobbs Ferrari was second, Andretti/Ickx Ferrari third, Rodriguez and Oliver fourth in their Porsche and fifth was the Vic Elford, Gerard Larrousse Martini 917.

Within minutes those rankings would change as cars came in for scheduled pit stops and driver changes but the Elford/Larrousse 917 would stay in the top 5 for the rest of the race.

Back in the pits NART driver Swede Savage was trying his best to replace a dead battery by himself. The NART mechanics were already engaged in trying to get another car up and running. Later he and co-driver Peter Revson would work together in switching out an anti-sway bar.

Because they had the largest contingent of Ferraris at Sebring in ’71 The NART pits seemed to attract several fans who hung around for hours watching the action and hoping to get a glimpse of the kind of yelling and disorganization mostly common to the factory Ferrari teams. For them it was light entertainment and they were not disappointed when George Eaton came in for a scheduled pit stop and driver change for his NART Ferrari 312 P.

Just minutes before there had been a little panic in that same pit when relief driver Luigi Chinetti, Jr. couldn’t find his helmet. Some thought it had been stolen and Chinetti began trying on other helmets but none would fit. All of this was accompanied by a lot of hand gestures, yelling and cursing and when Eaton jumped out of the car and into the pit he was told he had to go out again because of the helmet problem.

Being the stalwart fellow that he was Eaton got back into the now fueled car and back into the race. Not long after one of the crew said that Chinetti’s helmet was probably in the NART house trailer. Someone had placed it there thinking that Chinetti was in it taking a nap before his stint at the wheel.

At the Hairpin Turn the lunch wagon had just departed after dropping off boxed lunches to the corner marshals when Greg Young’s Ferrari came into the turn a little too fast due to brake fade. He barely made it through the turn going off the pavement and his car made contact with the sandbank on the other side of the track. The sandbank at that point was like a ramp and the Ferrari was launched into the air traveling some distance before landing on its nose. It then pivoted and landed on its top in a shallow culvert which prevented Young from opening the driver’s side door.

Three corner marshals were already running toward the car before it hit the ground and as they approached they could see that the driver was trapped and there was the odor of gasoline fumes in the air.

With the help of others, they lifted the car high enough for Young to begin exiting the car. As the driver was crawling away from the car it erupted in flames forcing all to retreat but the driver was safe and no one was burned. Young was examined by medical personal arriving on the scene but all he had was a few bruises. He was indeed very lucky that day. For their heroic actions the corner marshals were later honored with the Hayden Williams Sportsmanship Award.

Author’s Note: In the litigious world we live in tracks like Daytona and Sebring now prohibit corner marshals from “going over the wall” onto a hot track to assist any drivers involved in an accident. Their only “approved” action is to radio for help from emergency trucks stationed around the track. In my opinion, as an experienced corner marshal, if that policy had been in effect at Sebring in 1971 then Greg Young might not have survived that accident.

By the end of the second hour of racing the Andretti/Ickx 3-liter Ferrari 312PB had captured the lead demonstrating the competitiveness of the car compared to the 5-liter behemoths. Helping that competitiveness was the fact that they didn’t have to fill up as often doing at least 30 laps while the Penske Ferrari could do only 20. Andretti and Ickx would maintain the lead for four hours and had built up a four-lap lead when the car lost power at 4:10 p.m. and began to coast to a stop in the region of Big Bend and not too far from the Hairpin Turn.

As the 312PB coasted and stopped a huge cloud of smoke erupted from under the engine bay hood and corner marshals came running with fire extinguishers. The smoke was not coming from a fire but a huge crack in the transmission oil cooler case that drained the transmission of fluid resulting in a seizure. The car was retired after 117 laps.

With the demise of the Andretti/Ickx Ferrari the Alfa Romeo T33/3 of Nanni Galli and Rolf Stommelen assumed the lead on lap 118 but it was short lived as they had to pit twice to replace a battery and an alternator. The time lost for repairs allowed the Vic Elford, Gerard Larrousse Martini Porsche 917 K to go into the lead.

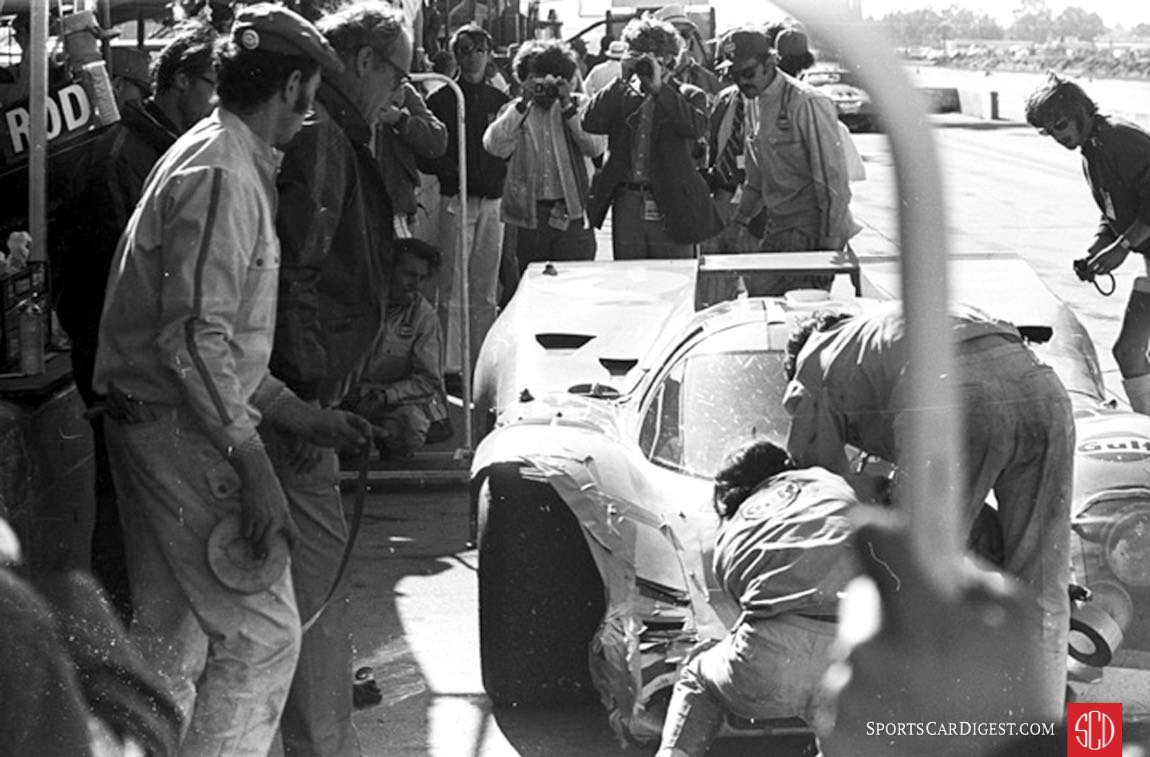

Around this same time the Penske team was about to receive a double dose of bad luck, as if having their 512M rear-ended at Daytona six weeks earlier wasn’t enough. The Donohue/Hobbs Ferrari came into the pits for an unscheduled stop limping along on a flat tire caused by running over a beer can thrown onto the circuit by a race fan. Time was lost changing the tire and when the car returned to the race Donohue was at the wheel determined to make up that lost time.

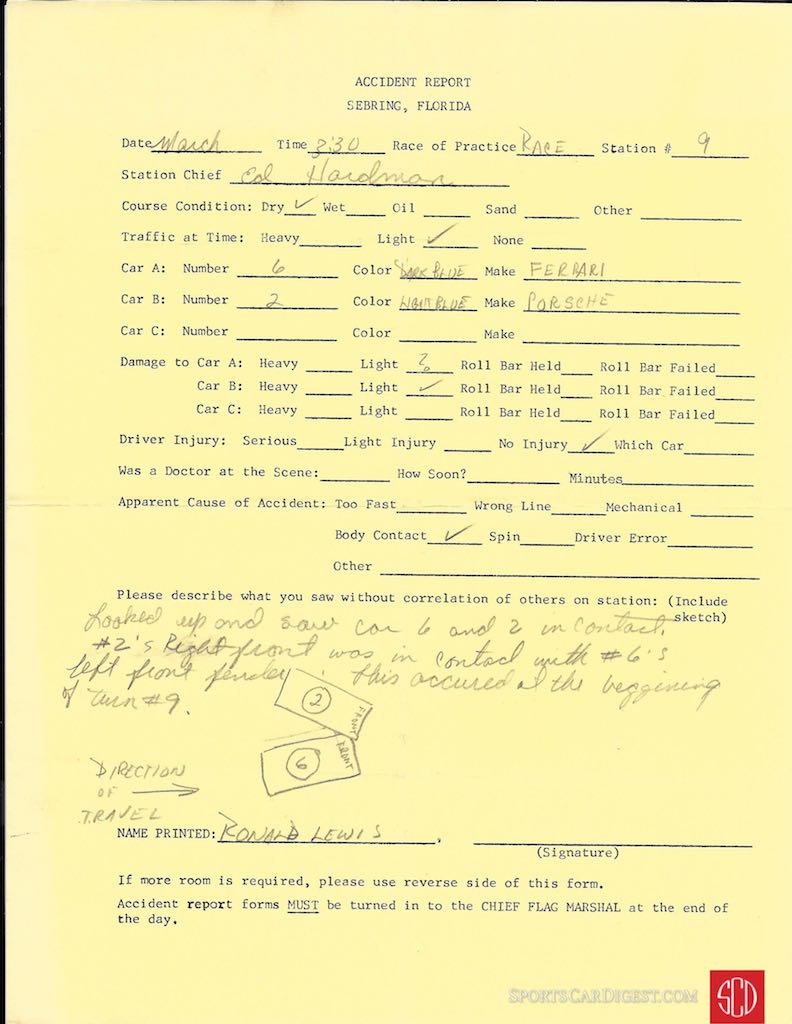

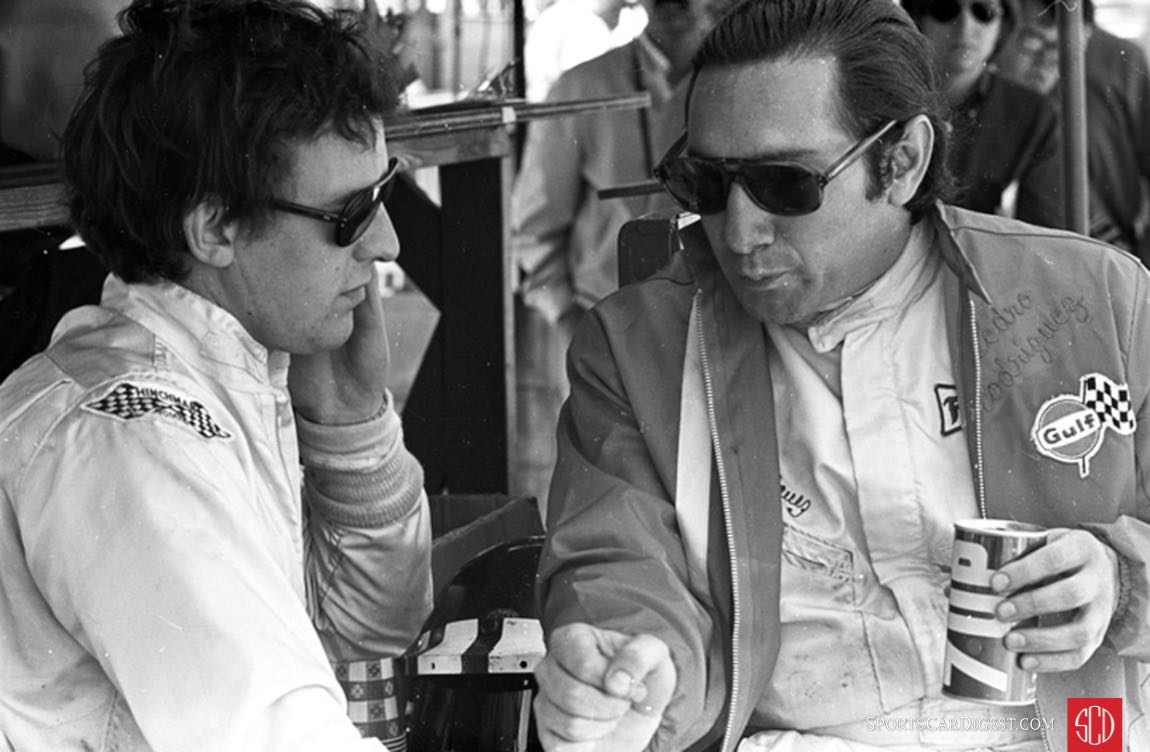

On the back part of the course, before entering turn 9, Donohue caught up to and was passing the Porsche of Pedro Rodriguez when contact was made. According to Donohue, Rodriguez hit his car three times causing significant damage to both. Coming out of the turn they slowed then continued to the pits to assess the damage leaving numerous bits of fiberglass and headlight glass in their wake.

Both cars entered pit road with the Porsche ahead of the Ferrari by several car lengths. Rodriguez drove right into the Penske pit area. In his bi-weekly serial called Don’t Wash Me car owner Kirk F. White, who was there in the Penske pits, describes what he saw and heard. “He (Rodriguez) threw up the door of the 917 and shouted at Penske saying, “You’ driver a loco gringo!” Mark came limping in behind Rodriguez. Painfully getting out of the car, he was utterly dejected. Roger did something he never did before. He used profanity in public. In a fit of justifiable temper, he shouted at Mark: “I told you not to f**k with Rodriguez!” Poor Mark’s face fell even further.”

With both cars now in the pits their crews immediately went to determine what repairs were needed. The Porsche lost its front right headlights and part of the fender over the right front tire. Duct tape was immediately applied to the damaged fiberglass but the headlight repair would have to wait until later. The initial repair took 4 minutes and 30 seconds before returning to the race. The damage to the Ferrari was more significant with left rear body work pushed in toward the tire and fuel cell vent damage. The vent had to be permanently shut which made refueling agonizingly slow losing them time they could ill afford.

In the opinion of most of the Penske crew it was all over and they should pack their bags and head for home. The only two holdouts were Roger Penske and Mark Donohue and they insisted they continue. It was a long race and anything could happen. When the car returned to the race, after almost an hour of repairs, they were 20 laps down. Regardless of what happened earlier on the track or who was at fault it became apparent later that the Penske Ferrari didn’t stand much of a chance of catching the leading Martini 917 or even finishing in the top three. Someone had to pay for this and that someone would be John Wyer’s Gulf Automotive Team.

Around 8:30 p.m. Penske went to the stewards and informed them that he would be filing three protests against the Gulf team. First he would protest the decision of the Stewards of the Meeting (SOM) to only penalize Siffert four laps for hitching a ride to the pits for gas when ten years earlier Stirling Moss had been disqualified for essentially the same infraction. Second, a protest would be filed against the Rodriguez/Oliver Porsche for insufficient body work following the collision with the Penske Ferrari and last a protest would be filed claiming the Siffert/Bell 917 failed to turn off its engine when it pitted on lap 149. No protest was filed against Rodriguez for deliberately hitting the Donohue Ferrari as Donohue had claimed.

No doubt some of the stewards groaned inwardly when the protests were filed because this was one big hot potato that could have ramifications well beyond the race and their decision would be inspected with a magnifying glass by every newspaper, motorsports publication and reporter both nationally and internationally. What made it so hot was the fact that they were dealing with the biggest names in the oil business (Sunoco – Gulf) and they were also dealing with two major racing team managers, Roger Penske and John Wyer. Added to the burden faced by the stewards was the threat by Wyer that he would withdraw the entire Gulf team of Porsches from the rest of the race if the stewards ruled against the Gulf team.

The decision of the stewards was as follows: In regard to Siffert’s 917 receiving a four-lap penalty the stewards decided it was sufficient for the infraction. Regarding insufficient body work over the fender of the Rodriguez/Oliver 917 the stewards ruled that sufficient body work did exist but the headlight had to be replaced, which was done, before darkness fell. The last protest concerned the fact that the Siffert/Bell 917 did not come to a full stop when it entered the pits and turn off its engine as required by the rules. The stewards pointed out that the car did not come in to refuel but to have a door slammed shut due to a faulty latch and an open gas cap shut. That was done as the car rolled slowly through the pit and then out onto the track. They had to do this one more time due to a faulty door latch. Like the others that protest was also denied

As the sun began to set around 6:30 p.m. the starter put out the signal for all cars to turn on their lights. Some had already come in to have headlight and driving light covers removed. To do that too early risked having your lights damaged or destroyed by debris from the crumbling track thrown up by leading cars. Some cars were equipped with the best driving lights they could afford because at night certain areas of the circuit were pitch black and the vast areas of concrete runway and taxi ways looked for all the world like a dark ocean with no landmarks or lights showing the way. Just about every year the race was run some poor soul would get lost on a remote part of the circuit. In the March/April 2016 issue of Vintage Motorsport noted German driver Jochen Mass, in his Memories of Sebring wrote, “….some drivers had lost their bearings (in the darkness) and one of them got lost for almost 30 minutes, trying to find the track again, his orientation obscured by the tall grass.”

On lap 149 Larrousse’s Martini 917 finally passed the Alfa T33/3 of Galli and Stommelen to take the lead and they would not relinquish it for the rest of the race. Having the lead, the Elford – Larrousse Porsche would travel another 110 laps and 572 miles to before taking the checkered flag at 11 p.m. This was the first victory for Porsche at Sebring since 1968. Those final six hours were without the drama of the first six and one motorsports writer referred to the last half of the race as “dull”.

That’s not to say the last half of the race for Martini was without incident. As the last hour of the race approached some in the Martini pits were keeping their fingers crossed while others began getting themselves cleaned up in anticipation of looking good for the photographers in victory circle. It was then they had one of those “Oh, no!” moments when the car pitted and was diagnosed with a broken exhaust manifold. Nothing could be done so the car returned to the circuit with Larrousse at the wheel while Vic Elford kept his vigil by the pit wall looking worried. Except for a quick refueling with minutes to spare the big flat-12 Porsche engine ran flawlessly and cruised across the finish line 3 laps ahead of the second-place Alfa T33/3 of Galli/Stommelen. The winning Porsche covered 260 laps beating Mario Andretti’s 1970 record by 11. It also racked up almost 1,347 miles which was another record and posted an average speed for the 12 hours of 112.500 miles per hour.

Nino Vaccarella and Rolf Stommelen came in third in their factory Alfa T33/3 and this 2-3 finish for Autodelta was their best showing at Sebring ever. The best the Gulf Porsches could do was 4th and 5th and some felt that if not for that incident with the Penske Ferrari 512M that Pedro Rodriguez and Jackie Oliver, in their Gulf 917, could have possibly been in the top three.

Despite some hard driving to make up for lost time Donohue and Hobbs finished a disappointing sixth overall in their Penske 512M being continually hampered by long refueling times due to the fuel cell vent damage. The Corvette of John Greenwood and TV personality Dick Smothers came in seventh and first in the over 2.5-liter grand touring class followed by George Eaton and Luigi Chinetti, Jr.’s Ferrari 312 P. The Porsche 911T of Jim Locke and Bert Everett finished ninth overall and first in the under 2.5-liter grand touring class.

One of the top finishing independent teams was Bruce Behrens Racing’s Chevrolet Camaro driven by John Tremblay and Bill McDill both of Orlando, Florida. They finished 13th overall and first in the over two-liter touring class. Bruce describes his time at Sebring in ’71 as follows:

“Our 1971 class win at the Sebring 12 Hour race was the culmination of a three-year effort. 1969 was a real heartbreak when the engine blew just 20 minutes before the finish. In 1970 it was very frustrating due to team personality conflicts and lug nut problems.

I feel that 1971 was our team’s crowning achievement especially since we overcame having to change engine parts on Friday night and into Saturday morning and then the problems with the brakes during the race. We were blessed to have raced during the ‘Golden Age of Racing.’”

In the above quote Bruce kind of glosses over the difficulties his car faced in winning its class. During practice and qualifying the heads cracked and there were no spares. A machine shop in Orlando worked all night Friday to supply new heads and they were dispatched to the Speedway at 5 a.m. on race day which was a two-hour drive under the best of circumstances. After they arrived the heads had to be installed and the engine was still being worked on when the car was pushed toward the starting grid.

For one reason or another the rear brakes on the Camaro never fully worked during the race and all the breaking effort ended up on the front brakes and tires. They went through eight front tires instead of the usual four as well as extra brake pads. The fact that they finished as well as they did and won their class spoke well of the entire team.

While the fireworks blazed overhead and the crowd celebrated, champagne was being served at the green and white patron’s tent in the paddock. More than one toast was made to the memory of Sebring and for many veterans of the race it was a sad moment sometimes interspersed with humorous stories about Fangio, Moss, Shelby, Castellotti and other legends from Sebring’s past.

After the ’71 race Alec Ulmann announced plans to build a new circuit if funding materialized. Some quietly speculated that Ulmann was trying to con the FIA into giving him an extension so he could hold another race on the same dilapidated race circuit. Well, it worked and a FIA sanctioned race was run in 1972 but the FIA, after realizing that Ulmann would never be able to build a new circuit, finally pulled the plug at the end of ’72 and that year was truly the “…last Sebring.” Maybe it was the last traditional Sebring for a few years but, like the Phoenix bird of Greek mythology, Sebring would rise from the ashes to regenerate itself and run again.

[Source: Louis Galanos]