John Grant is the current Chairman of the British Racing Drivers Club, and since taking on that role has had to make many difficult and radical decisions to secure the future of Silverstone Racing Circuit—The Home of British Motor Racing. Some may ask who is John Grant and how is he qualified to take such steps? In his career Grant has held positions in the highest echelons of both Ford Europe and Ford’s HQ in the U.S., and has been Chairman of the British RAC Motor Sports Association. VR’s European Editor, Mike Jiggle, spent time with him talking about his background both on and off the track, his passion for the sport from grassroots to international level and his high regard for the British Racing Drivers Club. In the first part of a two-part interview we look at Grant’s formative years and his career at Ford.

You’re now Chairman of the British Racing Drivers Club, but where did your love of motor racing begin?

Grant: I was born and spent my formative years in Northern Ireland, a hot bed of raw, natural motor racing talent and a great community for amateur racing on bikes and in cars.

The first motor race I really remember going to was the 1950 Tourist Trophy at Dundrod. I was supporting a young Stirling Moss, the up and coming rising star of British motor racing, who went on to win the race in Tommy Wisdom’s Jaguar XK120. Interestingly, Stirling remembers that as his first big international win—and I was there!! I was almost five years old at that time.

I went to most of the TT races, the last being in 1955. Of course, for motor racing, 1955 was a terrible year with the Le Mans tragedy and just a few months later three people were killed at the Tourist Trophy race, in two different accidents, too. Despite the accidents the, 1955 TT race was fantastic because all the “big boys” in motor racing were there—it was a great spectacle. Seeing the three works Mercedes 300SLRs, Ferraris, the single works

D-Type Jaguar in the hands of Mike Hawthorn and Desmond Titterington, all these great drivers and cars racing around the narrow country lanes.

Dundrod was quite close to your home?

Grant: Yes, around seven miles away from my home, I’d cycle around the course imagining I was one of the great drivers in the TT. Of course, motorbikes ran at Dundrod, too—John Surtees and Giacomo Agostini to mention just two names. Sitting in the grandstand overlooking the last sweeping, but sharp right-hand corner before they went onto the straight, I distinctly remember the line John took was totally different to anyone else, the bike would be leant over at a much steeper angle and he was considerably quicker than anyone else—such a master of his craft.[pullquote]“I noticed this novice driver in his Sprite…he approached the corner in a beautiful four-wheel drift, seemingly aiming right for me. Fearing for my safety…I ran from my position leaving my flags behind…. That driver was John Watson is his first ever race.”[/pullquote]

Of course we had road racing in Northern Ireland too, a tradition that carries on to this day, for both bikes and rallying for cars. My brother and I did many events, speed trials, rallies, auto tests, sprints, in fact the whole gambit of motoring competition open to us. These events were well organized, but very informal. We joined the Ulster Automobile Club and when I went to Queen’s University, I joined the University Motor Club that ran great road events.

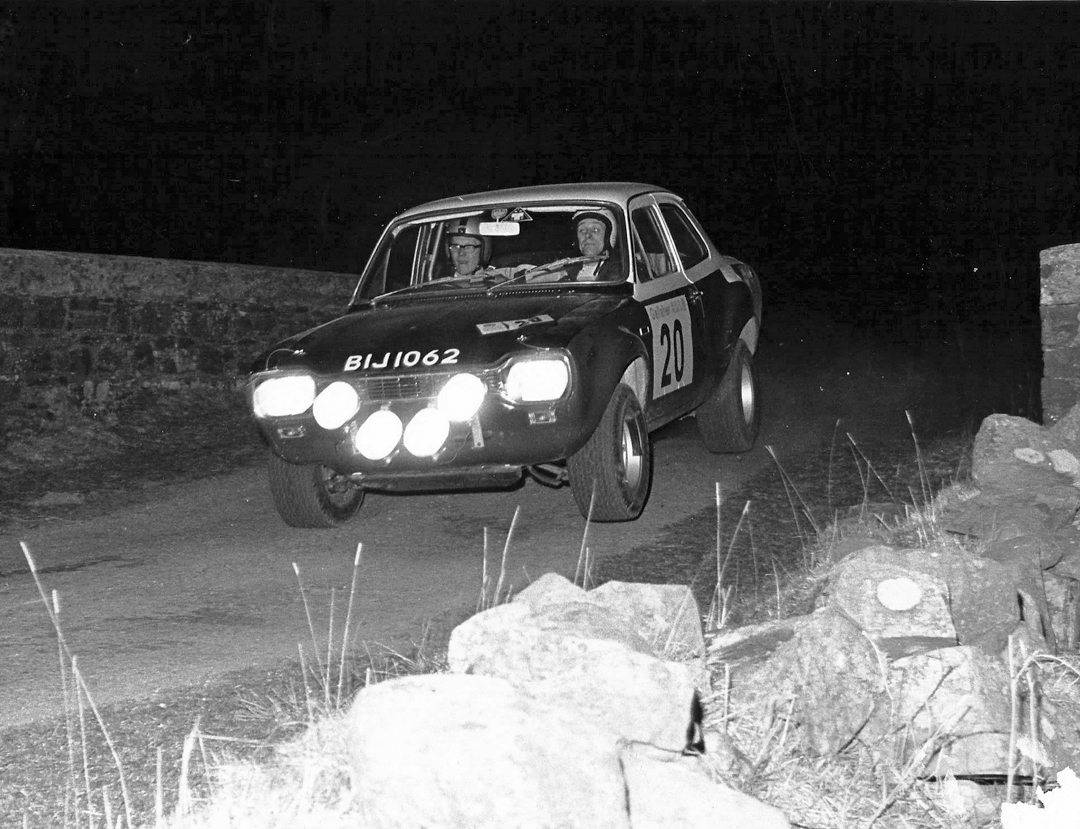

While at University, like most students I had no money, but was able co-drive on a number of rallies, including on a couple of occasions the Circuit of Ireland Rally with a chap called John L’Amie. John was a great racing driver who decided to do some rallying, and I became his co-driver. In those days, the regulations were such that you weren’t allowed any pace notes—I had done the Circuit of Ireland with pace notes previously, but in this particular year they were banned. I was calling notes from memory on some stages, which, as you can imagine, became quite hairy experiences. John had one of the very early twin-cam Escorts and Roger Clark was there in the works Escort, Paddy Hopkirk was there in the works Mini, and there were many other experienced drivers also competing. This was fine, but John didn’t see very well at night, so calling the bends became quite important. We were going quite well, having one of the quicker cars in the event, and rose up the leader board to 3rd overall from driving stages through Friday night to Saturday morning. The only cars in front were Hopkirk’s Mini and Clark’s Escort. Our next Special Stage was Sally Gap, a long drive over mountains southwest of Dublin—it was a very fast stage, which I’d experienced several times before. About 17 miles into the stage we knew we were up to 2nd place. On the last few miles, running in toward the finish, there was a particularly quick sector, around 80-85 mph. I called the next corner “medium right,” this meant John had to brake quite hard for it, he obviously didn’t hear my command so I shouted again with great vigor “medium right,” again I thought he hadn’t heard me, but then saw him pumping the brake pedal. With no brakes we went flying off of the road into the far black yonder of a peat bog. Crashing into the bog was quite fortunate as the boggy surface cushioned our landing–luckily we stopped the right way up on all four tires, but had lost any chance of finishing. Not the last time I experienced brake problems, as it turned out.

Another great driver I teamed up to navigate for was Robin Eyre-Maunsell, he has remained a really good friend—in fact my “best man” when I married. He went on to become a works Rootes and then Chrysler driver, winning the British Group N championship two years running with a Hillman Avenger and a Sunbeam Talbot. Robin’s even older than me, but still competes today—once it’s in your blood it’s always there. I did a full season of rallying with Robin in the Ulster Rally Championship. I think there were nine events and we had ten retirements!! Ten, because one rally was in two parts; a road rally followed by a stage rally—we retired with mechanical failure in the off-road stage, repaired it in time for the road stage and retired again. Our Hillman Imp was unreliable. Robin was unreliable, but it was a great learning curve for me, how to learn from other people’s accidents! The good thing was that I wasn’t paying for these misfortunes.

Photo: Grant Collection

What about circuit racing?

Grant: I used to flag-marshal at some of the local circuits. It was while marshalling at one circuit when I observed a young driver in an Austin-Healey Sprite. This is in the days when flag-marshals didn’t really have any barrier between them and the edge of circuit. On this occasion, I was at Bishops Court Circuit in Northern Ireland—Bishops Court, as many other motor racing venues, was a former RAF base. While mainly flat, the circuit did have some undulation. I was posted on the outside of a long sweeping right-hand corner, at the bottom of a hill. The cars would come along from the start/finish line turn about 60 degrees through a left-hand corner and then go down a hill toward me. On the first lap of practice, I noticed this novice driver in his Sprite—I was aware it was his first race—he approached the corner in a beautiful four-wheel-drift, seemingly aiming directly for me. Fearing for my safety, I was off! I ran from my position, leaving my flags behind. Looking over my shoulder, I saw that he actually controlled the car well. By the fourth lap I became more confident that the driver knew exactly what he was doing, so I stood my ground. That driver was John Watson, in his first ever race. Obviously, history shows he went right to the top only missing out on an F1 World Championship by a point.

As a matter of interest, what subjects did you study at Ulster University?

Grant: Economics, a singularly useless subject! Everyone thinks they understand economics, but nobody actually does. All economists are dual-handed—when asked a question, an economist will answer, “Well, on the one hand it could be like this, or on the other it could end up like that.”

Your qualification, however, took you into the highest echelons of Ford?

Grant: Yes, I had the choice of working at Unilever, or the Ford Motor Company. Both companies were renowned for their excellent graduate training programs. My decision was, do I make soap, or do I make cars? Obviously, I went for the car option. In total, I was at Ford for around 25 years. After five years, I left to get an MBA at Cranfield, England. Following a successful 12-month period of study, I was amazed to find that Ford wanted me back. They made me an offer to go and work in the U.S., which at that time was pretty unusual.

You must have made some impression in your first five-year term?

Grant: I guess I just bumped into the right people at the right time. I think many people have a career based being at the right place at the right time and meeting the right people. Personally speaking, I seem to have been in the right place quite a few times, and only occasionally in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Were you still involved in motorsport, or did work get in the way?

Grant: Initially, as a young graduate, my first year at Ford was pretty impecunious. My starting salary, in 1967, was £1,050 per annum. That was okay, but not a startling amount of money. I still took part in the odd rally, but it was done very much on a shoestring. I purchased a rally-prepared Imp for £210 from a friend of Robin Eyre-Maunsell and competed with that initially.

Were there doors you could open at Ford to enhance your motorsport?

Grant: Not really, although as a graduate, I worked in many departments to gain experience. I worked out the Public Affairs Department was closest to the rallying community at Ford. I had a session in that department, which got me out to Ford’s Boreham Rally HQ in Essex. On a couple of occasions I met some useful people like Stuart Turner—who I subsequently got to know well.

It would be around 1968-’69, motorsport-wise I continued to compete in my half-prepared Hillman Imp rally car. I used this as both my road and rally car but sold that and bought a 1071-cc Mini-Cooper S, second-hand, of course—I paid the princely sum of £330. I did everything in that car, autocross, sprints, rallies, I even did a rallycross event, too. I’d always drive to and from circuits in the car I used to compete. The rallycross thing was an exploratory venture as a good friend and I were thinking of undertaking a full season the following year. I suppose you could say I dabbled in anything and everything. I did all my own preparation and servicing of the car to keep costs down—it gave me great “hands-on” experience.

You say you worked in the U.S. for your second spell at Ford, what was it like to be the man from England?

Grant: It was unusual in those days to get that opportunity—I was very lucky and grasped it with both hands. In those days, it was commonplace to have Americans working in the UK and Europe, but not the other way around. Today, things have changed and more Europeans get to run things in the U.S. It opened many doors and got me exposed to a lot of different people within the company. Having worked in America certainly helped to “fast-track” me up the promotional ladder. I enjoyed the challenging environment at Ford. Whatever you said you had to back it up and support with facts—a very good discipline to learn.

Did you have an opportunity to continue with your amateur motorsport exploits?

Grant: Not really, although I had to have a go at something. Being in America, I wanted to have a typical enormous car. Through the Ford lease plan scheme, I leased a completely ridiculous car, a 7-liter Ford LTD 2-door. It was huge, the size of a battleship! The Americans have things called gymkhanas, similar to our driving tests, but slightly more open, so I just had to enter one of these with the LTD. Of course, my battleship was competing against much smaller sportier cars. In one event, I found a cunning trick. The hydraulic-steering couldn’t keep up with the stresses and strains of the gymkhana, so the LTD gracefully dumped fluid all over the starting line, which meant I could get away, but nobody else could. On one occasion, a gymkhana was run in Ford’s World HQ car park. I was there with the 7-liter LTD. The topic of conversation the next day was about “some idiot” who’d been seen driving the LTD in the event.

When did you return to the UK?

Grant: I stayed at Ford’s U.S. HQ for a couple of years, working in various financial departments. I was posted back to Europe and continued my progression up the ranks to some more senior positions. Obviously, as you move up the ladder opportunities arise to influence things, which I really enjoyed. After rising to the height of Treasurer of Ford of Europe, I was managing billions of dollars of foreign exchange risks and investing huge amounts of cash. Believe it or not, this was great fun and very satisfying. During this period, I became part of the team that looked at the possibility of Ford purchasing Alfa Romeo, but I’ll expand on that later.

Photo: Bill McMahon

From there, my career took a significant jump to become Vice-President of Corporate Strategy for Ford of Europe, giving me a seat on the Executive Committee, the main board for Europe. At that stage, I came across Jackie Stewart who’d done a great deal of work for Ford, and Walter Hayes too, he was in charge of Public Affairs. I worked alongside both men on a reasonably regular basis on a number of things. Corporate Strategy got me involved in all sorts of motorsport related stuff, including the rallying side with Stuart Turner. I recall Eddie Jordan coming to “tap me up” for some Ford cash for his proposed move to Formula One, which I managed to resist, although someone else in the organization was persuaded. After just a year, in 1989, I was asked to move back to the U.S. to head up the Corporate Strategy team in America. It was a time, too, when Ford U.S. had recognized it might be a good idea to have Europeans in some senior positions. Looking back, I think this was the best year of my entire career. The Ford business was doing well on a global basis, the car industry was healthy and the company was full of confidence.

With things going so well there was a move driven by Ford Europe to get involved in the more premium end of the car industry. Ford has always been a major producer and supplier of vehicles for the “blue collar” market rather than the top end—the various “bean counters” always blocked previous moves toward that goal. For Ford to move in this direction would mean a change in culture and philosophy. Toyota was about to do something along those lines by launching the Lexus brand, but Ford’s culture just couldn’t make that work. It was a fact widely recognized among the senior hierarchy at Ford. New “low cost” producers entering the market from Japan and Korea meant we would soon be under attack, so we decided to adopt a strategy to move toward the faster growing and more profitable mid and luxury ends of the market. The purchase of Alfa Romeo was considered to satisfy the mid-end objective and names such as Jaguar and BMW were put on the table to consider making offers for the luxury brand. However, BMW was soon off limits as the Quandt family made it very clear that they were not going to sell out to Mr. Ford.

There were numerous funny stories emerging from our team who’d been sent to work out the feasibility of purchasing Alfa Romeo. Alfa was owned by an Italian government organization called “IRI” which in effect was a hospital for sick companies. After a little digging we found Alfa Romeo had been in this “hospital for sick companies” since 1931!!! Just looking at the headcount of employees was farcical, various figures were presented, but we ended up with two figures, the difference between them being a mere 13,000. These turned out to be in the Casa Integrazioni, a body of people within Alfa Romeo who did absolutely nothing, they didn’t even appear at work, but were nominally on the company payroll and paid a full salary by the Italian government’s Casa Integrazioni…this could only happen in Italy. Alfa Romeo was haemorrhaging cash. There was a multi-storey car park across the road from the main Alfa Romeo building filled with cars. A colleague asked if this was the staff car park, but was surprised to be told, “No, it was stock.” Apparently, this three-story car park was full of Alfa Romeo 90s, which had been out of production for around 18 months. Most of the cars had been sold to the Italian Police—we worked out they still had around three years’ supply! Ultimately, the Alfa Romeo deal fell through when Fiat woke up to the fact that Alfa Romeo could fall into unfriendly foreign hands, so they eventually took it on board. That was an interesting “warm-up” before we looked at other companies.

Photo: John Grant Archive

SAAB were the next on our agenda. We had very nearly done a deal with them in 1988. We’d shaken hands and only had to sign documents in the following few days to complete the deal when we pulled the plug. The deal floundered due to previous discussions we’d had with Jaguar when Sir John Eagan was at the helm. Those initial talks had stalled, but Jaguar later had a re-think and wanted to come back to the table. Ford’s dilemma had been whether to take on Saab, or Jaguar, or both—I recall some intense meetings at the Dearborn HQ, some of the most colorful of my entire career. We knew all the “ins and outs” of Saab, we knew less of Jaguar, but it was a great brand with history, heritage and an established position in the luxury car market, albeit with many problems at that time. The ultimate decision was to go with Jaguar. Unfortunately, I got the job of informing the Chief Executive of Saab just as he was going into a celebratory dinner to acknowledge the tie-up between them and us. It was a very difficult call—not a nice thing to have to do. Later, GM took over the deal with Saab as we went ahead with Jaguar.

How did the culture of a very British company and a very American company mix?

Grant: Together with a number of my colleagues, we knew that Ford had the ability to screw things up and dilute this premium brand, so we tried to put things in place that would stop this happening. The first thing was not to fill Jaguar with Ford executives, but to keep many of the current Jaguar management. We particularly didn’t want any Ford styling people to get involved—there was one U.S. senior stylist who really wanted to get into Jaguar, but we went to great lengths to ensure he didn’t. Although we did put three Ford executives (including me) into top positions, we would only put more Ford people into Jaguar if the Jaguar team requested it, thus hopefully preserving the “magic” of Jaguar that had so appealed to us. Bill Ford Sr. was appointed as an ex-officio officer of the Jaguar styling committee as we knew he was passionate about the Jaguar marque. I was moved back to the UK to help sort things out at Jaguar.

With such a rich Jaguar heritage in motorsport, how did this fit in with Ford philosophy as motorsport seemed to survive in spite of Ford rather than driven by Ford—would you agree?

Grant: Yes, that’s quite true, particularly through the 1970s and 1980s. The Rallying Department was very successful under the guidance of Stuart Turner as I’ve already touched on, but he had a pretty low budget to work with and had to work a bit under the radar you could say.

The old adage “win on Sunday, sell on Monday” wasn’t the Ford way, necessarily?

Grant: No, it wasn’t. It was a very different climate to today. Leaping ahead, the motorsport activities with Jaguar were very interesting, because it was the final days of Jaguar being involved in sportscar racing and I had the interesting experience of working closely with Tom Walkinshaw—a really colorful character and great fun to be with. He did a fantastic job for Jaguar.

I’ve interviewed many drivers who have Tom on their list of best team managers to work with?

Grant: Not just drivers, he built a strong team behind him too. We had to keep our pockets zipped up when we dealt with him, but he did a great job winning those World Championships for Jaguar and twice winning Le Mans—would have been three times had it not been for that damned Mazda!!

I started to get on with my job as number two at Jaguar; the number one guy was Bill Hayden. He was a real hard manufacturing guy and did a wonderful job of overcoming Jaguar’s then dire quality and productivity problems. My job was to oversee product development, sales and marketing—which, to be honest, I had very little experience of. Ultimately, I was there to protect the Jaguar brand and to keep everyone in line with the adopted strategy. This also involved overseeing our motorsport activities. I was fortunate to be at Le Mans in 1990, when Jaguar won and 1991 when Mazda finished ahead of three Jaguar XJR12s. Jaguar’s sportscar program was complicated as we had the long distance XJR12 V12-engined cars in Europe for races like Le Mans, Spa and Nürburgring and the XJR11 3.5-liter twin-turbo V6 cars for the shorter distance races in Europe. There was a separate team of long distance XJR12s running in the U.S. under IMSA rules, but with different engine capacity, and we had XJR 10s and subsequently XJR16s, the 3-liter version of the V6 twin-turbo cars, for shorter U.S. IMSA races. Added to that, TWR was developing the phenomenal Ross Brawn-designed XJR 14 with Cosworth V8 engines. It was sometimes difficult to manage what was, in effect, four racing teams. While sponsorship had paid for much of these race teams, sponsorship money wasn’t growing, but the cost of running them all was and the deficit was getting bigger. We had Silk Cut in Europe and Budweiser in the U.S. and Castrol to a smaller extent across all teams. Our problem was that sports car racing didn’t attract large TV audiences or press interest, even though we were experiencing some of our most successful years. We were spending around £10 million a year in 1991 but felt we were not getting value for that investment. At the end of 1991, we pulled the plug on sportscar racing for those exact reasons, although we did do some of the early U.S. races in 1992.

I used my motorsport contacts within Ford to explore if we could use our global resources more effectively. Ford of Europe were involved with the Formula One Benetton team with Cosworth, but were trying to extricate themselves from that to divert their funds to World Rallying that was more closely related to their production models. Ford U.S. wanted to remain exclusively on U.S. motorsport programs like NASCAR. With Jaguar pulling out of sportscar racing it made sense for us to consider the feasibility of switching our budget to Formula One. This was 1991—way before Jaguar actually went Grand Prix racing. Our reasoning was we had a great relationship with Tom Walkinshaw (who was running the Benetton team with Flavio Briatore), the Benetton family was enthusiastic about the brand synergy with Jaguar and the Ford Group felt it was a better way for all parties to get better value from the money being invested in motorsport.

At that stage, we worked out that Jaguar could have done Formula One for around the same money as it was putting into the sportscar programs, but with the global TV audience for Formula One would be much more effective in helping to grow the Jaguar brand. The other fortuitous reason was that Cosworth was developing a V12 engine that they were already running on a test-bed, ready to launch with Benetton in 1993. This was wonderful because it would give credibility for Jaguar taking over the Formula One program with a new “Jaguar” V12 engine. Mercedes was also warming up to a Formula One return under the banner of Sauber, so it would have been fascinating to recreate the rivalry with our “old enemy” on the Grand Prix circuits of the world—Jaguar vs. Mercedes. Things progressed to quite a detailed level, even including how and where the Jaguar logo would fit onto the cam covers of the new Cosworth engine. We were pretty close to doing this when both Cosworth and Benetton found the new V12 engine simply wouldn’t work due to cooling and packaging issues. Cosworth instead decided to adopt a new version of the V8, which would do nothing to enhance Jaguar’s profile. So Jaguar sadly decided to withdraw from racing. Would it have worked? Jaguar in F1 at that time? Yes, I believe it would have, although costs would soon have escalated, making it a difficult call.