Cars don’t come much better than this. Born in a golden era of sportscar racing, this French beauty has the most amazing pedigree. Raced at Le Mans by Juan Manuel Fangio and Louis Rosier, driven in the Monaco Grand Prix by Maurice Trintignant and currently in ownership that dates back to 1958, this car is the real deal. This car is French royalty, it has blue blood, it is…true blue.

One thing is certain, success in motor sport sells cars. In the late 1940s, success on the world’s race circuits was seen as a must for Talbot-Lago, so alongside the construction of its road car projects, the marque embarked on the production of an out and out racing car. This machine was designed to be capable of winning Grand Prix races and, in its sportscar form, Le Mans.

Huge effort was placed on the production of this range, of which this chassis 110057 is one example. Originally intended for the 1950 Le Mans 24-hour race, 110057 was not completed early enough, and so missed the race. Once it had been finished though, it was acquired by the 1950 race winner, Louis Rosier, who entered it into the 1951 Grand Prix d’Endurance.

Keen to taste the victory champagne again, and looking for another victory in the world famous event, Rosier enlisted the help of Anthony “Tony” Lago’s friend, Juan Manuel Fangio. Fangio would share 110057 with Rosier, while his fellow countryman Froilan Gonzalez would drive with Onofre Marimon.

Fangio and Gonzalez had been racing Talbot-Lago T26C cars in Argentina, at the end of the previous season, and were now given plum roles at Le Mans in sports car versions. Fangio and Gonzalez expectantly travelled to Le Mans, with the young Marimon in tow. Marimon was regarded as Fangio’s protégé, and for Le Mans he would be handed his first European start as a teammate to Gonzalez, who himself was less than three weeks away from driving a Ferrari to the Scuderia’s first F1 success in the British Grand Prix at Silverstone.

The Argentinian trio made a welcome addition to the Le Mans entry, and the Talbot-Lago ranks and hopes for success were high.

The pace of the 1951 race was intense. Despite conditions as bad as they ever had been around the Circuit de la Sarthe, the competitors, when flagged away for the 4 p.m. start, raced off readily. The new Jaguar XK120C machines were flying the flag for Britain, and would eventually win, but at the end of the first lap it was Gonzalez at the wheel of a Talbot-Lago who flashed passed the packed tribunes as leader of the race. Vive la France!

The winning Jaguar would eventually eclipse the Talbot distance record set the previous year, when the two Peters (Walker and Whitehead) covered 2243.9-miles at an average speed of 93.49 mph. The winning car also finished nine laps clear of the Pierre Meyrat/Guy Mairesse Talbot-Lago, and with a lap record by Stirling Moss also in the bag.

Despite these statistics, however, Jaguar did not enjoy it all their own way. The Argentinian-led Talbot-Lago attack was impressive and, when the weather allowed, Fangio displayed his fabled talents. Moss had been fast earlier in the race, but between 8 and 10 p.m. Fangio was able to show his skills, and he was fast! With light drizzle falling, Fangio was still able to clip a margin of two seconds off the lap record Moss had previously set.

Photo: Pete Austin

As darkness descended the Talbot-Lago attack was still in a strong position to keep pace with the British machines. French honor was being upheld. Fangio led the attack in car #6, while Marimon and Gonzalez matched their performances with car #7. But troubles were ahead.

During a routine stop, as darkness cloaked the track, 110057 showed the first signs of pressure. With Rosier now at the wheel, the car blankly refused to start and the bonnet was removed. A small fire ensued, but was quickly extinguished by a mechanic. Further attempts to start the car were made, and finally after much arm waving from Rosier the 4.5-liter fired into life. Back in the race, but with valuable time lost, things began to unravel.

By 5 a.m., both 110057 and the Gonzalez/Marimom car were out. An oil leak ended the charge for 110057, while a gasket failure forced the other “star” car out of the running. It was left to Pierre Meyrat and Guy Mairesse to represent Talbot-Lago in the charge for victory. It was a race France would not win, as the duo finished 2nd, nine laps behind the leader. A new order had been established, and a French car would not win Le Mans again until Henri Pescarolo and Graham Hill took victory for Matra in 1972.

Following Le Mans, 110057 was re-bodied by Carrozzeria Motto, thus enabling it to wear closed-wheel sportscar bodywork. This allowed the car to be brought into line with the new regulations laid down by the Automobile Club de l’Ouest for the race. The car was entered for the 1952 Monaco Grand Prix carrying the number 64, with Rosier and Maurice Trintignant at the wheel, but it retired after 37 laps.

For 1953, 110057 was sold to George Grignard, and in his hands the car continued to compete on a regular basis in French events. It was also entered to appear in the 1954 Le Mans 24- hour race, with Grignard sharing with Guy Mairesse. Mairesse had finished 2nd in the 1951 race with Pierre Meyrat in another Talbot-Lago T26 GS, but sadly Mairesse was involved in an accident a few months prior to Le Mans in the Coupe de Paris at Montlhéry. Swerving to avoid a stalled car, Mairesse crashed. The accident would claim his life, as well as that of a six-year-old boy among the spectators.

Following the accident, 110057 was locked away out of sight and left virtually untouched on its transporter until 1958, when it suddenly found new light. While searching for spare parts for his father’s Talbot, Richard Pilkington enjoyed a meeting with Anthony Lago. Mentioning an interest in the now-retired Talbot-Lago Grand Prix cars, their conversation quickly led Pilkington to a nearby garage and the chance look at a single-seater Talbot-Lago. The car offered for sale was far too expensive, but spotted at the back of the garage was a damaged sportscar that was painted in the famous Talbot-Lago blue!

The front bodywork had been damaged in Mairesse’s Montlhéry crash, but the car itself remained mechanically intact. Repairs to drive it back to the UK were soon able to be completed and, in the end, all that was needed was one front wheel and a replacement radiator. Upon arrival in the UK, its new owner carried out an extensive restoration, including returning 110057 to its original cycle-fender body style.

Under the same ownership today, 110057 has indeed led a very active and full life. It has been in regular track action since 1961, and is without doubt one of the best known, best loved and most recognizable historic racing cars in the world.

THE MAN BEHIND THE NAME

Antonio Franco Lago, known as Anthony or Tony Lago, was born in Venice in March 1893. Awarded the Legion d’Honneur by the French government for the glory he brought France through his automobiles, Lago’s blue cars played an important part in the halcyon period of motor racing.

Buying the French Automobile Talbot company from the collapsing Anglo-French combination of “Sunbeam Talbot Darracq,” he was able to found the Talbot-Lago marque and manufacturer cars that would carry the name to international success in racing events around the globe.

Photo: Pete Austin

Lago’s early days were spent in the company of actors, musicians and government officials as he grew up as the son of an owner and manager of a theater. He developed strong relationships with individuals, notably Angelo Roncalli, the man who would later become Pope John XXIII, as well as Benito Mussolini. Graduating from the Politecnico di Milano with a degree in engineering, Lago joined the Italian Air Force in 1915, where he achieved the rank of Major during the First World War. A founding member of the Italian National Fascist Party, Lago later became an outspoken critic of the political movement, which led him into dispute with Mussolini. With political tensions high, Lago carried a grenade with him as a measure of personal safety and, on one occasion, a gang of fascist members entered a trattoria looking for him. Guns were fired and the grenade thrown, with Lago escaping through the backdoor of the building and fleeing to France.

Travelling on from France to the United States, Lago commenced work for Pratt and Whitney, the aero giant, in California before returning to England during the 1920s. It was here that Antonio changed his name to Anthony, and was able to progress his industrial career. He became technical director for L.A.P. Engineering and then Self Changing Gears Limited, a company that manufactured Wilson pre-selector gearboxes. Displaying his business skills, he persuaded Sunbeam Talbot Darracq, and other companies, of the gearbox’s merits, and many units were subsequently supplied and fitted to cars.

During the 1920s, Talbot’s factory overspent on its quest for success in Grand Prix racing and Lago, after some conversations, convinced Sunbeam Talbot Darracq, the British parent company, that with him at the helm the brand could grow and be back on its feet within a matter of months. His salary was paid during a period in which he transformed the company. The company also agreed to share any profits and helped Lago’s three-pronged rescue plan for Talbot. This involved reducing expenses, the construction of light, sporting cars, plus the use of these vehicles in racing for development and publicity—with the racing examples closely related to production models.

Moving to France in 1933, by 1935, Lago was able to convert the Wilson gearbox license he held into an option to purchase the Talbot factory located in Suresnes, a western suburb of Paris, when Sunbeam Talbot Darracq made the decision to close it. Thus was the Talbot-Lago marque born.

The following year Lago arranged for Walter Becchia to produce the Talbot-Lago T150 model, and Lago himself masterminded the car’s promotion. Three cars were painted in red, white and blue to match the French flag. Lago entered them in a Concours d’Elegance in the Bois de Boulogne, and the cars arrived driven by female racing drivers all wearing outfits to co-ordinate with the vehicles. The marketing technique was a great success, although car sales proved to be slow due to the French economy. Lago, the marketer, made sure his cars maintained a strong profile by getting one to cover a distance of 100 miles in one hour at Montlhéry.

Lago later announced plans to build a 3-liter, V16-engined car for the 1938 Grand Prix season. Blueprints were drawn, and shown to a government department that was tasked to achieve national success with public money, and some funding was achieved. The Talbot-Lago V16 sadly never appeared—but Lago’s engine and its drawings were inspiration for Raymond Mays, Peter Berthon and British Racing Motors, who eventually managed to enter a V16 into Grand Prix events during the early 1950s. Indeed, during 1939 Raymond Mays was invited to drive one of the team’s unsupercharged, 4500-cc cars in the French Grand Prix at Reims. Mays later wrote in his book Split Seconds that he was “Particularly flattered by the works’ invitation because the car earmarked for me was the prototype single-seater of a series which has since won a distinguished record in post-war Grands Prix.”

Despite his skills as a businessman, Lago struggled to keep his business out of receivership and it slipped four times into this limbo. At the end of 1950, when finances crumbled, it would bring an end to the factory-supported racing effort. Juan Manuel Fangio’s superb drive at the wheel of his friend’s car in the Argentinian Rafaele 500-mile race was the team’s swansong. While Fangio and Froilan Gonzalez raced Talbot-Lago cars in Argentina, the Talbot factory was going under in France. Racing cars continued to compete under customer branding and the banner of private individuals, but the factory team days were over. Lago kept his overall business afloat until 1958, when he sold it to Simca in a deal signed-off in 1959. Just a handful of months later, in December 1960, in Paris, Lago passed away.

STORY OF THE MARQUE

As mentioned, Lago stepped into the breach, in 1935, when Sunbeam Talbot Darracq collapsed. After acquiring the business it soon became internationally recognized as Talbot-Lago. Corresponding with these changes, the British interests in Talbot were taken over by the Rootes Group and the parallel use of the Talbot badge in France and Britain subsequently ended. Talbot-Lago cars sold in Britain were then to be badged as Darracqs!

Lago began to introduce a new range, and many of these were penned by Walter Becchia. Many of them featured transverse, leaf-sprung, independent suspension. The four-cylinder, 2323-cc T4 “Minor” was shown at the Paris Motor Show of 1937 and the six-cylinder, 2696-cc “Cadette 15” was also introduced alongside the six-cylinder, 3996-cc “Major” and its long-wheelbase sibling, the “Master.” These were all classed as touring cars, with the solid aim of appealing to the Frenchman for his family.

A sporting range quickly followed led by the “Baby 15,” a lighter version of the “Cadette 15.” The sporting range centerd on the six-cylinder engines that Lago had mastered so beautifully, and the range stretched to include the coachwork styling of Figoni et Falaschi in an aerodynamic styling on the luxurious Lago-SS.

Photo: courtesy of the Automobile Club de l’Ouest

During the early years of World War II, Becchia left the company to work for Citroën and Lago was joined in 1942 by Carlo Machetti. The two combined well and work began on the twin camshaft, 4483-cc, six-cylinder unit that would underpin the 1946 creation, the Talbot-Lago T26.

Following the war, the company was well-known for its production of high-performance racing cars and for a range of large passenger vehicles. Components were shared across the platforms, but with money tight after years of European conflict the automobile industry was fragile. Talbot-Lago was not the only manufacturer to struggle, and finances quickly became stretched.

The Talbot-Lago Grand Sport (GS) was first displayed to the public in October 1947, as a shortened-chassis car. Only 12 were made during 1948, which marked the model’s first year of production. It was a fast car, and its speed impressed. At the time, it was one of the world’s fastest production cars.

The car was built for speed and used the 4.5-liter, inline, six-cylinder aluminum cylinder head and triple carburetors from the T26 Grand Prix racers. The chassis details were similar to that of the Grand Prix cars too, only slightly longer and wider. Most Talbot-Lago cars were sold with bodies manufactured by Talbot fitted, but the GS was different. Cars were delivered to waiting customers as a bare chassis, prompting the purchaser to choose bodywork from a coachbuilder, ensuring the car’s sporting heritage.

The T26C went on to become one of the most iconic Grand Prix machines of all-time after making its track debut in 1948. French Blue had never been so exciting, and using an unsupercharged, 4.5-liter engine, mated with a Wilson pre-selector gearbox, the car was an instant hit. Louis Chiron drove an example to 2nd position in the 1948 Monaco Grand Prix, and in 1949 Louis Rosier won the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa-Francorchamps with Chiron taking the win in the French Grand Prix.

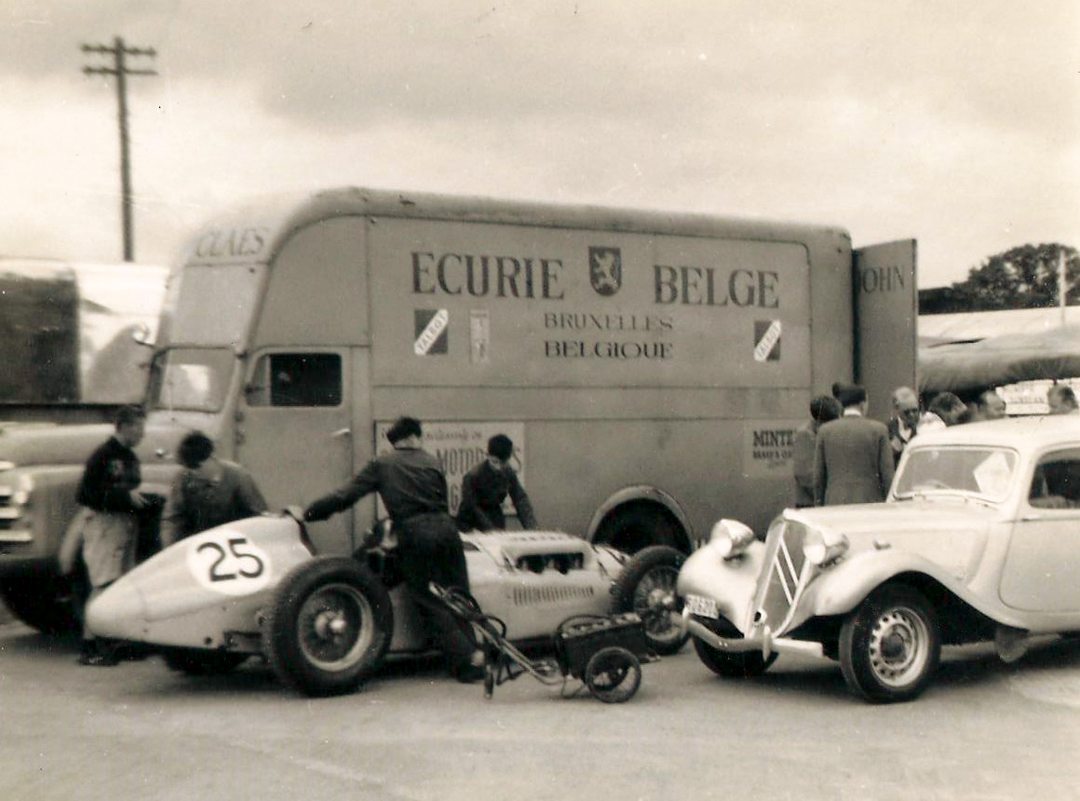

Prior to the construction of our profile car, its sister example won Le Mans in 1950 driven by the father and son duo, Louis and Jean-Louis Rosier, and Talbot-Lago racing cars were commonplace in leading Grand Prix and European racing events. Louis Rosier, Louis Chiron, Philippe Etancelin, Johnny Claes and Duncan Hamilton, to name but a few, could be seen behind the wheel of these machines on a regular basis.

Road models continued under the cloud of the ever worsening company finances, and for 1952 a series of new Pontoon-bodied cars were produced, headed by the range-topping Talbot Baby/6 Luxe—using the much-loved six-cylinder as its beating heart. At the 1954 Salon de l’Automobile de Paris, Talbot-Lago put on show their last new engine. A four-cylinder, with twin laterally mounted camshafts, was of 2491-cc and found its way into a car in 1955 when it was mated to the Talbot-Lago 2500 Coupe T14 LS. Originally designed to be all-aluminum, later examples enjoyed more extensive use of steel. Fifty-four examples were built, but they proved a hard sell.

Photo: James Beckett Collection

The body style struggled to disguise the car’s roots back to the 1930s, and the engine was not regarded as the world’s finest either. Encountering this engine problem, Talbot-Lago was forced to buy an engine for its 1957 creation, and a 2476-cc BMW unit was chosen. With export plans, the car was badged the Talbot-Lago America, and constructed as all other French cars then were, with the driver positioned on the left-hand side of the car. Reception from the public was poor, and only a handful of cars made it off the production line.

With the company now in apparent financial free fall, Lago decided to accept an offer from Simca president Henri Pigozzi for the sale of the brand to Simca during 1958—with the sale completed the following year. The end of Talbot-Lago was actually a sad affair. Tony Lago’s best efforts to keep his brand alive ultimately failed. Empty pockets required him to sell and stave off bankruptcy. Many times throughout the 1950s Lago tried to recapture the golden era for his beloved creations, but he was unable to do so, and hence the racing days from 1948 to 1951 remained the golden era for his company.

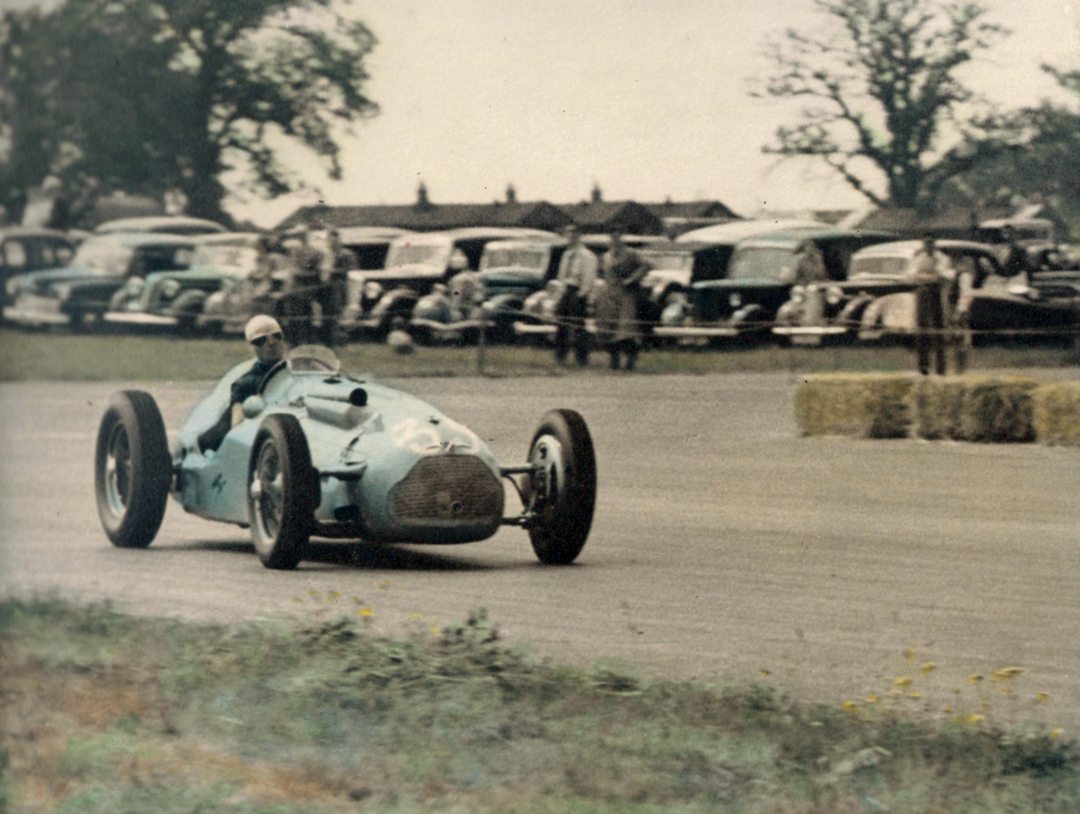

DRIVING A PIECE OF HISTORY

On a sunny summer morning at Silverstone, The Home of British Motor Racing, I was handed the opportunity of a lifetime—to drive a car that not only raced in the Monaco Grand Prix but also the Le Mans 24 Hours. This car was not only raced by greats such as Louis Rosier and Maurice Trintignant, but also the legendary maestro himself, Juan Manuel Fangio.

I must say that over the course of the past year, for some reason I have been more than lucky with the chance to drive several ex-Fangio machines. Tasting a Fangio Chevrolet Coupe, I was able to experience what the great man would have felt charging across the rough Argentinian terrain during his early motoring encounters. In the IKA Torino, I was able to believe I was the 24-time Grand Prix winner and five-time World Champion going about his daily business in a road car he used for his daily commute. Now, I was being given the chance to unleash the power of the 4.5-liter Talbot-Lago that he had raced with such skill in 1951 at Le Mans.

Photo: John Pearson Collection

This car had the capability to win that race, and if it had, then it would have written an even larger chapter in motor racing’s glorious history books. Saying that though, the space it fills is already large and I will be honest, its fine history left me with a tingling feeling and an air of anticipation as the clock ticked toward my chance to climb aboard.

Greeted by Richard and Trisha Pilkington, I chatted with them about the Talbot-Lago. This car has formed part of the Pilkington family for many years, and they both enthusiastically told me tales from its past, stories of yesteryear and how it has been raced actively by Richard since 1961. Goodwood is regarded as the mecca of historic racing nowadays, but it is worth a note that Richard raced this car at the track prior to its closure. Despite his long stewardship of this rare vehicle, Pilkington has made the tough decision to allow the car to move on, and has entrusted noted London-based dealer Gregor Fisken to help him find it a new home.

Once our static photographs were “in the can” it was time to climb aboard, and in a car of this period I decided my period crash helmet was the “done” thing to be wearing. A big step took me onto the seat and then a wriggle behind the wheel, and I was in! Feeling more like Fangio with every beat of my heart, I was now in the position to relish the chance of firing the engine and engaging drive.

Before that was possible, it was time for Richard to give me a quick lesson in cockpit instruments. Really there weren’t too many for me to take in, but he was keen to know that I had full understanding of the car’s pre-selector gearbox. In truth, I had not driven a Le Mans or Grand Prix thoroughbred of this type before with a pre-selector, but having had a little previous experience of its type, I was confident that no harm would be done!

Such is the value of this car, and given the constraints at Silverstone for my drive, I have to say that my driving of this thoroughbred was more of a canter along the gallops rather than a Group 1 race at Longchamp for the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe. But, like a jockey who enjoys the chance to ride a thoroughbred, I enjoyed every second of driving this four-wheel steed.

Photo: John Pearson Collection

The beautiful 4.5-liter engine roared into life as soon as I asked, and sliding the pre-selector out of neutral and into first gear I pressed the gear change pedal, positioned where the clutch pedal might be, and I was off. As simple as that—I was now in the land of Fangio, and I must say quite pleased with myself.

As I have already intimated, I was unable to go roaring around, sawing at the wheel like Gonzalez would have but instead was prescribed a controlled drive that would allow me to sample the car and return it safely to its owner.

The driving position for me was good, I felt safely tucked in behind the large steering wheel that offered up a feeling of safety. A fair size wheel, it gave plenty to hang on to and the steering was sharp and quick. The car’s engine gave a reassuring resonance through the chassis and to me the car eagerly wanted to be raced, it wanted to be challenged and asked to do more. I could also tell that it was not entirely comfortable driving at the pace I was asking of it!

A slogan used by the organizers of the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe says, “Ce n’est pas une course, c’est un monument.” This translates from French to English as, “It’s not a race, it’s a monument.” I can’t help but think that this applies in a similar manner to this machine “It’s not a racing car, it’s a monument”—Ce n’est pas une voiture de course, c’est un monument. Something everyone should have the chance to admire.