Benetton’s standing in F1

Like many of today’s Formula One teams, the Benetton outfit morphed from an existing team, Toleman, then itself became Renault and today it is operating under the banner of Lotus F1. Benetton first began competing in its own right beginning in 1986 with the Benetton B186-BMW. The team’s first drivers were Teo Fabi and Gerhard Berger, with the latter giving the team its first win at the Mexican GP, the penultimate race of the year, following a season that had been dominated by the Williams and McLaren teams. Prior to competing under its own name, the Italian clothing brand Benetton had sponsored Tyrrell, Alfa Romeo and Toleman, bringing along a certain vibrancy to the outward appearance of the cars with their striking liveries. This joie de vivre embraced the team as a whole in later years with the charismatic Flavio Briatore at the helm, flamboyant car launches and disco music booming from their pit garages. Benetton portrayed a totally different speed of Formula One, way ahead of its time and with a style that, indeed, is now emulated up and down today’s F1 pit lane. During its history it courted controversy too, as well as changing the team nationality from British to Italian in 1996.

Their first car, the Benetton B186, was simply a Toleman in Benetton clothing—sorry about the pun! It was designed by Rory Byrne, Toleman’s chief engineer, who would become a key component of the future for both Benetton and Ferrari as well as, more importantly, Michael Schumacher. Formula One at that time embraced turbo engine power, and the B186 was fitted with BMW’s version. The following season Benetton turned to Ford for its engine, but “the writing was on the wall” for turbo power as it was to be banned from the start of the 1989 season. The team would become virtually a Ford “works” team with regard to engines during this transitional time, and as such was a force to be reckoned with, regularly finishing right behind the might of Williams and McLaren in the Constructors table.

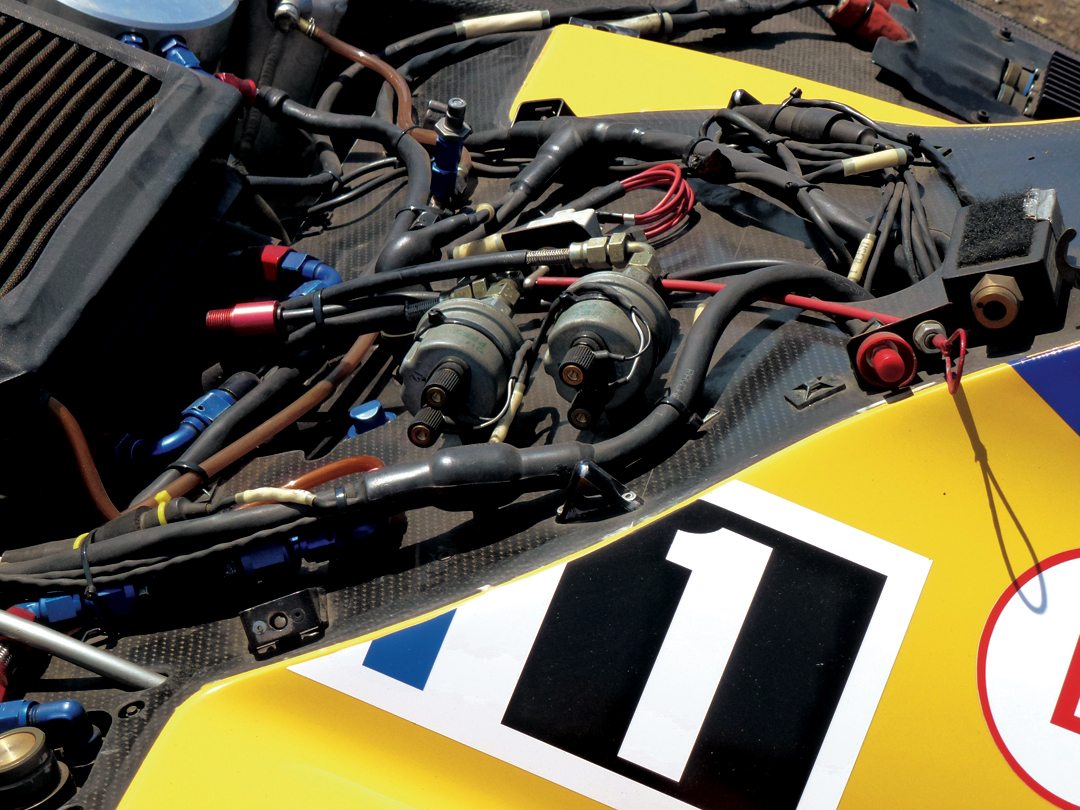

Our profile car is the B192-08 campaigned in the 1992 season when, once again, Williams and McLaren were the cars to beat. Gizmos such as semi-automatic gearboxes, ABS and active suspension were the “new way to go.” Benetton had realized that money from the family fashion business alone wasn’t sufficient to keep up with the “big boys,” and supplementary sponsorship was needed, which came from RJ Reynolds Tobacco’s Camel brand. An alliance between the two was officially unveiled for the 1991 season, with the Camel livery becoming a prominent replacement for the multi-colored Benetton fashion brand. On the driver front, things were heating up as well. The “new kid on the block” was Michael Schumacher, who first raced for the team partway through the 1991 season after making his debut with Jordan. His first full season in the F1 World Championship found him teamed with Martin Brundle, a seasoned campaigner who had spent time at Tyrrell, Zakspeed and Brabham. While he hadn’t set the world alight with his performances, Brundle was a solid racer capable of a good placing in the right car, and offered a certain balance. Tom Walkinshaw, whose TWR Group had taken a third stake in the Benetton team, advised them about both drivers since he had observed them in his sportscar days—Schumacher had raced in the Mercedes Junior team, while Brundle had won the World Sportscar Championship in 1988 with Jaguar and Le Mans with TWR Jaguar in 1990. So, with the right car, the right engine and the right drivers, could Benetton mount a strong challenge for the elusive World Championship?

It must be remembered that a number of key personnel who came from Benetton went on to form the “Ferrari Dream Team” including technical director and race tactician Ross Brawn, designer Byrne and technician Nigel Stepney, all of whom would join sporting director Jean Todt at Ferrari to help Schumacher and the Scuderia to win an unprecedented five consecutive drivers titles and six consecutive Constructors Championships.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

Benetton B192

The B192 was designed by Rory Byrne and Ross Brawn. Byrne had designed the Toleman TG280-Hart that dominated the 1980 European Formula Two Championship. He was also responsible for all the Toleman F1 cars, including the TG184 that launched the career of Ayton Senna at the memorable 1984 Monaco GP. Brawn had also been Walkinshaw’s designer of the Jaguar XJR-14 that had won the 1991 World Sportscar Championship.

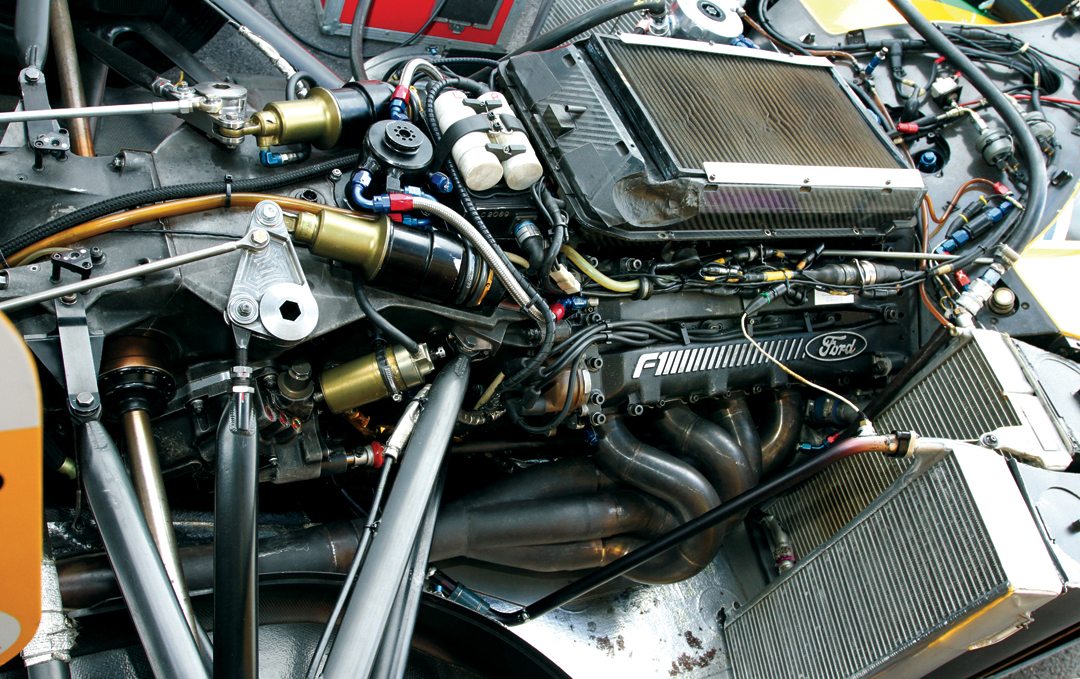

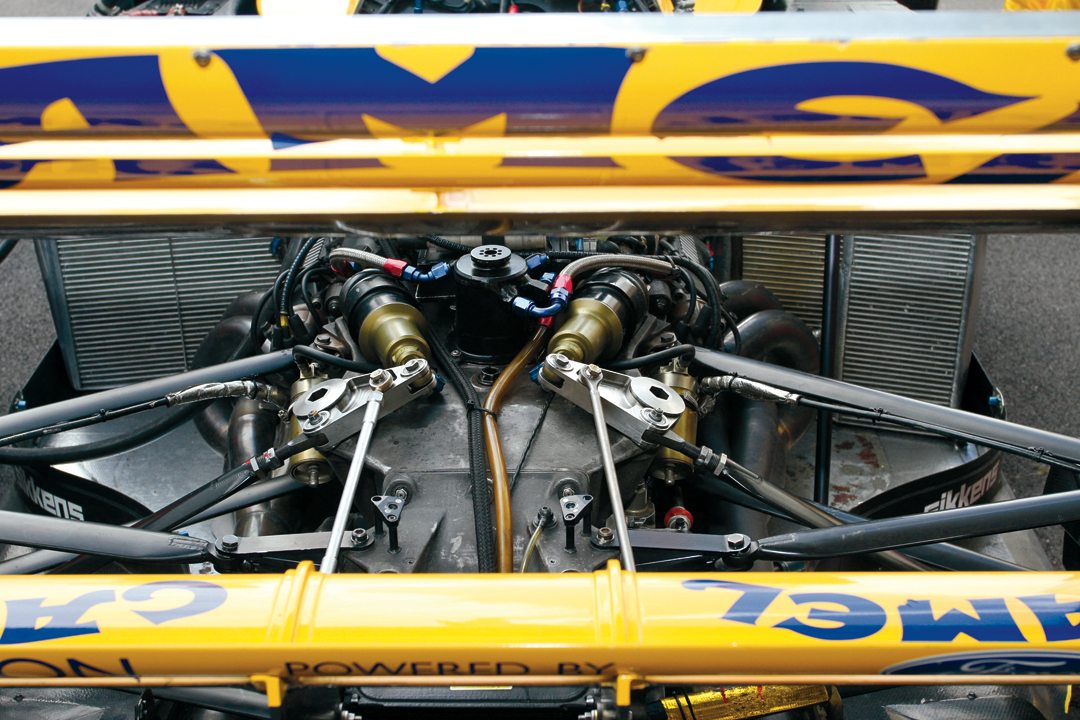

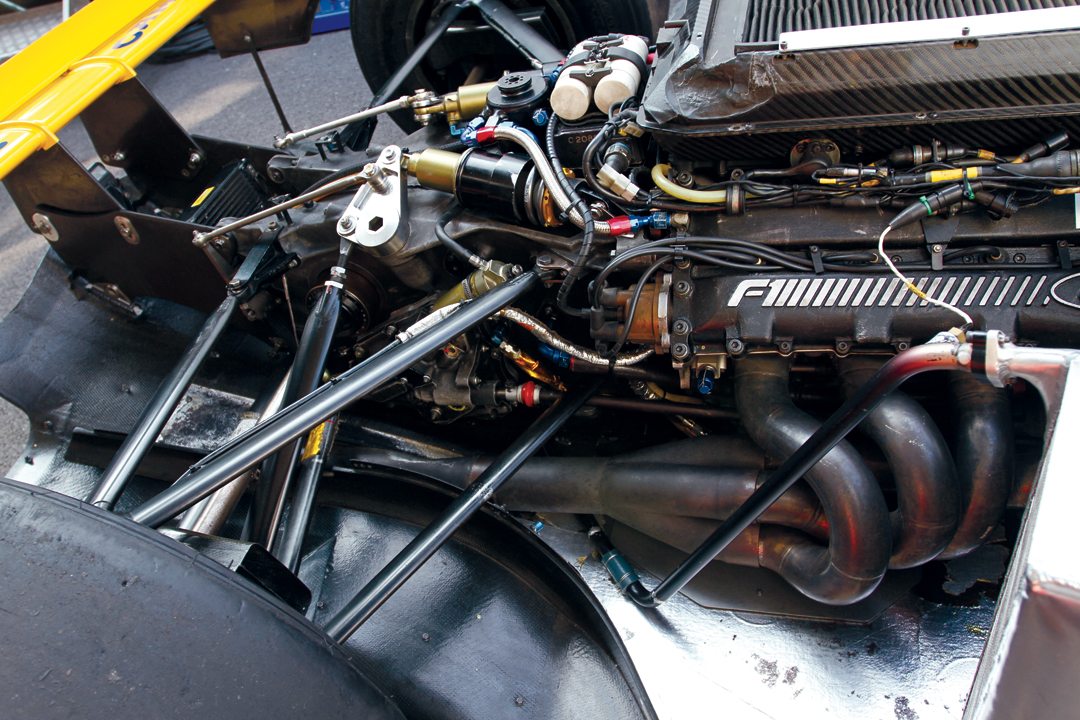

The new car was an obvious progression from the B191B, but with a lighter and more nimble chassis. It was, however, a strictly passive car, and while the Ford V8 engine lost out in the power stakes to some of Benetton’s rivals on the grid, it would prove a very reliable unit as the season progressed. Both the Series VI and VII engines used pneumatically controlled inlet and exhaust valves. The Series VII engine was the fastest-running V8 to date with a maximum speed of 13,500 rpm. The Electronic Engine Control system (EEC) was increased from 1.5 million commands with Series VI to 1.7 million on the Series VII, and the engines were exclusive to the Camel Benetton Ford team. Intense wind tunnel testing allowed the team to perfect the airflow over the car, while other modifications to the suspension geometry and gearbox were aimed to get the best out of the Ford V8 power unit. Brawn described the B192 as “…a perfect example of the restructuring of the technical department at Camel Benetton Ford and the formation of a solid engineering base from which we can build for the future.”

Photo: Pete Austin

Brundle and Schumacher notched up considerable testing laps during the development stages of the new car, with Brundle heading most time sheets. He was very pleased with the new car straight out of the box, yet it missed the first three Grand Prix races of the 1992 season in South Africa, Mexico and Brazil. Instead, a B-specification version of the 1991 challenger (designed by John Barnard and Mike Coughlan), sporting modified suspension and bodywork components, was used in those first races. The B191B notched up a 4th and two 3rd-place finishes for Schumacher, but Brundle retired from all three races—causing him briefly to question his ability.

The B192 first hit the racing tarmac at the Circuit de Catalunya in Spain, but found itself a bit overmatched by the new Williams FW14B-Renault as designed by Adrian Newey. Rainy weather plagued the weekend, but Nigel Mansell and the Williams continued to be a very strong combination, having won the three previous races. During qualifying the B192 was a second slower than the all-conquering Williams, and a blistered tire compounded the problems as Schumacher uncharacteristically crashed on the wet track and broke his Benetton’s chassis. Undaunted, the Benetton duo battled on, with Schumacher qualifying 2nd on the grid, 2.5 seconds faster that teammate Brundle in 6th. In the race, Mansell reigned supreme until lap 40, when more wet stuff fell from the sky. Schumacher was running 2nd, some 15 seconds adrift, with Senna holding 3rd. The last 25 laps looked to be a true fight to the finish with both Schumacher and Senna gaining ground on Mansell by two seconds a lap in the inclement conditions. The gap reduced to just four seconds, but when Mansell realized he was in jeopardy of losing his perfect win record he fought back, using different lines and charging like a typical Spanish bull to rescue the situation and take a clear win. Both Schumacher and the B192 showed their pace, however, with a strong 2nd-place finish. Brundle, re-established himself by having his first finish of the season in 6th place, claiming a single World Championship point for the team. The B192 had made a mark on the 1992 F1 World Championship and given the team great confidence, but could this first outing’s success be sustained throughout the season? The team knew it couldn’t outrun Williams, but McLaren was on the radar as the team to beat.

Photo: Pete Austin

As the season progressed both drivers had their share of problems, with Schumacher retiring in San Marino, France and Hungary, but Brundle having just a single retirement in Canada. Equally, when things went well Schumacher finished no lower than 4th and Brundle 5th. The high point was Schumacher’s first Grand Prix win at Spa, as the dominant Williams cars suffered cracked exhausts and finished 2nd and 3rd with Brundle 4th. After Portugal, there were just two races left. At this stage of the season Schumacher was 3rd in the driver standings, with 47 points; Brundle stood 6th with 30 points.

Benetton B192-08

Our profile car first raced at the last two races of the 1992 season, then the first of two races of the 1993 season in South Africa and Brazil, but by this time it had been upgraded to a B193A spec.

So, Suzuka, Japan, and the Fuji Television Japanese GP was the race debut of this car in the hands of Michael Schumacher who was aiming to retain his 3rd place in the Drivers Championship—he had to beat Senna. Continuous rain blighted any progress with setup changes for the race, so Michael had to be satisfied with the norm, knowing that while the car was reliable it was not a fighting machine. He qualified 5th behind both Williams and McLaren drivers, making the best of a bad job. Unluckily, on lap 13 of the race Schumacher found a gearbox full of neutrals and had to retire—not the result either he or the team wanted.

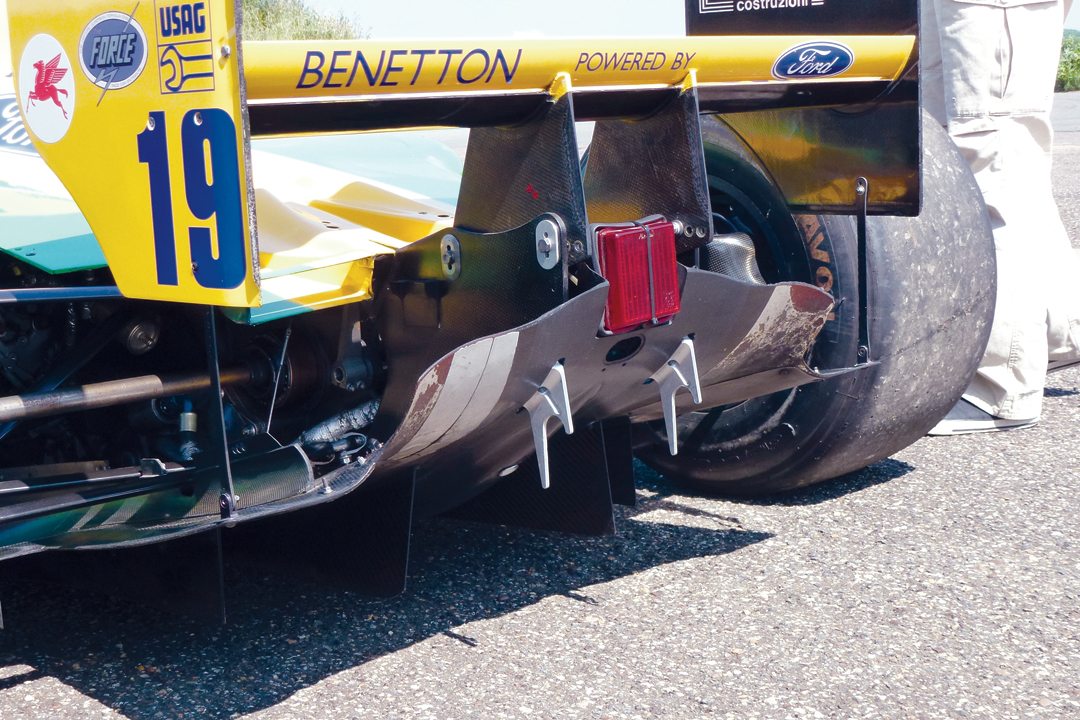

On to Adelaide for the final race of the season, and with the championship already in Mansell’s hands many races ago (Hungary), it was 3rd place that Schumacher was pushing for. Following his crash in Japan he was three points adrift from Senna. The Benetton was fitted with the Series VI Ford V8, rather than the Series VII engine, as the team thought it offered greater driveability on the Adelaide street circuit. Again, as in Japan, Schumacher found himself in 5th position on the grid. The top two protagonists, Mansell and Senna, took each other out, leaving the way for Berger to win for McLaren and Schumacher to take 2nd and gain sufficient points to take that 3rd spot in the Drivers Championship.

Photo: Camel Benetton Ford Press Pack

For 1993, B192-08 became B193A-08 and was raced by Michael Schumacher. The car was completely overhauled and now featured reworked aerodynamics and cooling system, revised front suspension to accommodate the new front wheel widths, and now had a semi-automatic transmission and active suspension.

For the first race at Kyalami, South Africa, Schumacher took third spot on the grid behind pole man Alain Prost, now at Williams, and Senna in the McLaren. Midway through the race, Schumacher tried a bold move on Senna, going for a marginal gap, but the unyielding Senna ensured Schumacher’s demise as they touched and the Benetton driver joined the retirement list.

The next race, and last for our car, was in Brazil. It was a race full of incident with a rainstorm midway through to spice things up. Schumacher came in for dry tires as the weather changed and a dry line formed. At the stop the car managed to fall off the jacks—very unprofessional. Then, in his haste to catch up, Schumacher overtook at a waved yellow flag and was given an instant pit-lane drive-through penalty. At the flag, local hero Senna won, with Damon Hill in the “all singing and dancing” Williams 2nd ahead of Schumacher in 3rd.

Michael Schumacher is seen here in the B192 during the ’92 F1 finale on the Adelaide street circuit where he finished 2nd to Gerhard Berger’s McLaren.<br />

Photo: Mike Cotes

Photo: Pete Austin

Photo: Pete Austin

Photo: Camel Benetton Ford Press Pack

Photo: Mike Cotes

Testing the B192-08 by Lorina McLaughlin

When the Michael Schumacher B192-08 (in passive configuration) came up for sale in the States, I was still competing in a McLaren M23, and although I had enjoyed some amazing races throughout Europe for a number of years—including twice at the Grand Prix Historique de Monaco—I felt that I wanted to race a more modern Formula One car. With this latest news of the sale, it seemed it was meant to be. The Benetton that Michael raced to 2nd in the Australian Grand Prix, elevating him to 3rd in the World Drivers Championship was destined to be my next iconic car!

The first time I drove the car was on the Silverstone Stowe Circuit, which was used more as a test track at the time and is situated within the complex’s Grand Prix circuit. Coincidently, this was also the first track where Michael Schumacher made his debut test in a Formula One car, for Eddie Jordan. They called him in after just six laps as he was going so quickly that they thought he would crash…. Well, he certainly shot to stardom in his debut Grand Prix soon afterward, qualifying 7th for his first race at Spa! The fact his Jordan didn’t last a lap was of no consequence, Michael had arrived and Benetton beckoned.

All was not exactly ideal for my first test session, as they had to pack foam rubber all around and on top of the existing seat, so that I could reach the pedals and be able to see out! Even then it was quite a struggle to reach them because I am so petite. There just hadn’t been time to get a new seat made.

My pulse rate quickened as doubts swirled around in my head; cold tires, easy to stall, stiff suspension. I had visions of a skittish Benetton darting across the track, the complete opposite to my driving style, but that’s the biggest difference with these modern cars, they have much more downforce and therefore need much stiffer springs. Fortunately, weather conditions were good and although apprehensive I did feel excited sliding myself down into the Benetton’s narrow cockpit. Once strapped in, I clicked into race mode. I was back in familiar territory, a Formula One cockpit, albeit a different one, but it was good to get behind the wheel again. I checked the instruments, now as familiar as the McLaren’s to me as I’d done my homework religiously over the previous few weeks.

Photo: Mike Cotes

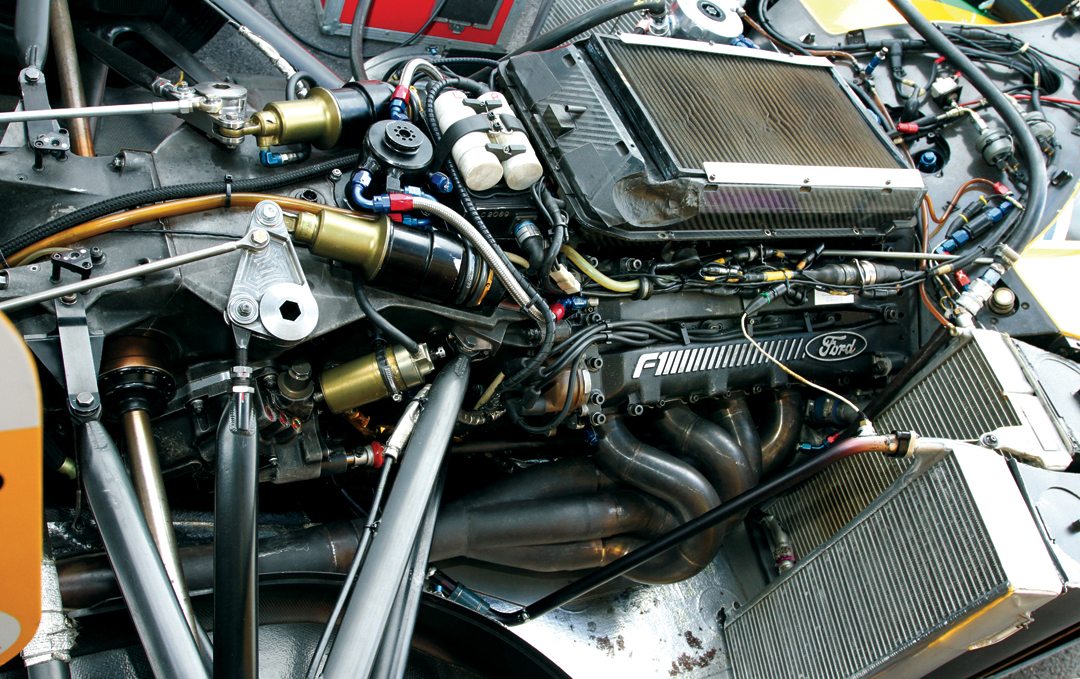

With my heart pounding and the adrenaline surging through my body, I flicked the switch on the right of the digital display panel sideways to activate the Pi system, then, like clockwork, I flicked the switches down on the left hand side, click, click, click: ignition, ECU unit and pump, leaving the final switch untouched, as it’s the rear red light, used in the rain. I took a final glance at the pressure and temperature readings on the digital display screen, before raising my right hand for the team to start the engine.

Wham! The Ford HB burst into life. The thrilling sound of the 3.5-liter V8 screaming behind your head is like nothing else. Another shot of adrenaline surged through my body as I blipped the throttle to check the rev band flashing across the digital screen, remembering that 11,000 rpm was the limit. I then selected first gear, and with huge trepidation eased my foot off the clutch and, to my great relief, managed to exit the pits and blast down the pit lane and onto the track without stalling!

This was always going to be an exploratory test, just to get a feel for it, check the seating position, the instruments, the suspension, the gearbox, the tires, the acceleration and brakes, which were awesome! That I was testing on this small triangular-shaped track less than a mile long was, to be totally honest, not brilliant. But hey! Look who’s tested here before. This is like another one of those “meant to be” situations, so just get on and let’s go for it!

As it happened, I could barely get into second gear before having to brake, select first gear and power slide through the bend. Then stretch my foot onto the accelerator and select second gear, I was now racing down part of the runway, the widest part of the track, where a battalion of cones funnelled the racing line to keep me on course.

Everything was happening in nano-seconds: as soon I put the power down, it felt as though the next bend rushed up before I had time to think, let alone, check the instruments, dab the brakes and change gear! I had to brake hard at the end of the runway section, down into first, I could feel myself slipping down inside the cockpit, the foam rubber just wasn’t enough, but no time to worry about that, there’s the second medium-fast left hand bend coming up fast. I managed to brake, change and turn into the bend. As I exited, I grabbed second then quickly got on the brakes before turning right and then immediately left onto a short straight—it felt as though I had been catapulted through that last section, but there was still another short straight before hitting the brakes, change down and power through the final sweeping left hand bend to cross the start/finish line and complete the lap.

This was something else, unlike anything I had driven before, and I was on a complete high afterward. I felt I was walking on air. The adrenaline was still pumping through me so all my senses were on high alert. I felt so ALIVE!

Yes, the suspension felt much stiffer than the McLaren’s setup and no, I wasn’t comfortable, but I couldn’t wait to have a longer session. The Benetton had given me a taste of what was to come and I wanted more, but with my own seat and the pedals repositioned and moved toward me. That would be a major job and take some time to sort, but it would need to be done before my next event.

A FLYING LAP OF SYWELL AERODROME

It had been a race against the clock to get my Benetton prepared and I was very grateful to my team, lead by Roger Heavens, former World Sports Car and European Touring Car winning driver of the ’60s and ’70s, who had worked miracles so that the Benetton could be delivered to Sywell in good time.

After several disappointing breakdowns over the last couple of years, primarily down to gearbox issues, I was feeling both excited and apprehensive at the prospect of having some new gears in the gearbox and a brand-new clutch that would have to be bedded-in for my runs at Sywell. Apart from knowing that the clutch was lighter than the previous one, I had little knowledge as to the gear ratios and whether or not they would be suitable for the Sywell Aerodrome. After all, I had yet to see a circuit map or even the circuit layout, which was tricky as it was an operating airfield with a fairly bustling runway! I had a suspicion this could be interesting.

Another issue giving me cause for concern was the life expectancy of my engine, which I need to prolong as much as possible. I was very conscious of not over-revving it and keeping within the 11,000 rpm limit.

The first time I viewed the course was on my first run! Naturally concerned about the new gearbox, I took the first two laps fairly cautiously, so I will take you on a flying lap at Sywell, my final run on Sunday…

Everything was running well since the previous three runs, so after doing a final systems check and getting the oil and water up to temperature—which takes about an hour-and-a-half—my team pushed me into the assembly area to await my turn. The worst thing about the track is it has zero grip. Because there is no regular racing on it, the surface is green, there’s no rubber on it at all, so there’s no grip, it’s just like driving on ice. In a straight line, it’s fine, no problem, but when you have to change direction and cross onto the runway, you have to be really smooth crossing the grooves in the concrete, otherwise you could lose it in a big way!

Without the luxury of tire warmers or new tires, I needed to get some heat into my Avons quickly, so wheel-spinning off the line at about 8,000 rpm in first, the back stepped out. At this point, I had to keep the power on to pull it out of the slide and accelerate up through second, third, watch the revs! Then dab the brakes and turn in for the first right-hand bend, which can be taken pretty fast, around 140-150 mph, but keeping it very smooth. It’s so difficult with the change of surface as you turn onto the runway, you’re driving across the grooves in the concrete and, as I mentioned before, without any rubber down, there’s absolutely no grip.

Another quick dab on the brakes, then power it through the corner, but holding it as smoothly as possible since I could feel it wanting to break away. As soon as it had straightened, with the nose pointing up the runway, I started to increase the power, and change up through third, fourth and fifth gears on the way to 11,000 rpm—around 180 mph—then braking very, very heavily, to change down into second gear for the hairpin at the top of the runway. It’s quite a physical lap, especially with the crosswinds along the back straight. I had to hang on like mad to prevent being blown off the runway as the Benetton continued to dart about. I probably felt it more than most because of the car’s huge wing end plates.

Approaching the hairpin, I accelerate gently around it as I’m crossing the grooves in the concrete on the runway again, and as I exit the corner I accelerate away toward the bend, up through second, third, fourth, fifith, taking it almost flat, then down to the bottom, braking, changing down and again driving smoothly over the grooves and down toward the return road to finish a flying lap.

Stepping out of the car, I was fizzing, on a real high. It’s the most wonderful feeling in the world! I think how lucky I am to own such iconic cars and I have to pinch myself; is this really my life and was this all meant to be…?

Martin Brundle’s view of B192-08

The Benetton B192-08 had only just been restored to its original Camel livery when Lorina received a surprise request from the BBC F1 TV team, via the British Racing Drivers’ Club. Their F1 television commentator Martin Brundle, who was Michael Schumacher’s teammate in ’92, wanted to test the car for a special F1 television feature, to be shown during the British Grand Prix weekend at Silverstone.

Martin recalled the test, “It’s like stepping into an old friend, you immediately notice all the little details that you had forgotten about and it feels comfortable, it feels familiar. Bits and pieces that were poking into you, hurting your legs, hurting your arms, for me it was quite a compromised environment, but it also felt familiar.

“I thought the HB engine was a tremendous engine, very driveable, but super sensitive to any kind of over-rev; if you came down the gearbox a little too quickly, or you missed a shift and over-revved it by 20 rpm, it would come out!”

His voice quickened as he recalled his “stella” season. “I had a lot of good results in the B192. In fact, my best ever year in Formula One was in that car. It’s a very simple car in many respects. It was so effective, it was so easy to drive, so easy to set up. While we were against the all-conquering Williams that year, with all their semi-automatic gearboxes and all sorts of gizmos and goodies, our car was very simple but very effective so it would work everywhere. Set up was just a bit of tweaking here and there for different race tracks; you could just get in and drive it, and so it proved to be that day when I drove it around Silverstone, it just felt exactly as I remembered it.”

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Carbon fiber composite monocoque manufactured by Benetton Formula. Ford V8 engine installed as a fully stressed member attached to the rearmost monocoque bulkhead

Wheelbase: 2880 mm

Track: Front: 1818 mm, Rear: 1720 mm

Length: 4075 mm

Height : 950 mm

Width: 2140 mm

Suspension: Double wishbone and pushrod with Benetton-designed and manufactured damper units all around

Engine: Ford F1 Series VII Engine, V8 (75 degrees), 32 valves (two inlet and two exhaust per cylinder)

Cooling System: Water/air radiators in each sidepod. Engine oil/air radiator in right hand sidepod.

Electrical: 12-volt electrical system utilizing lightweight batteries.

Displacement: 3494-cc

Fuel System: ATL rubber fuel cell mounted within monocoque structure behind cockpit

Power: 700 bhp

Transmission: Benetton transverse 6-speed gearbox. Double-plate clutch

Electricals: Ford Electronics

Brakes: Benetton-spec Brembo one-piece calipers and master cylinders with carbon fiber discs

Acknowledgements / Resources

Vintage Racecar would like to thank Lorina McLaughlin for test driving her Benetton Ford B192 and her team, headed by Roger and Alex Heavens of RH Motorsport.

Special thanks to Martin Brundle, Sky TV F1 commentator, for his time, patience and genuine interest in this feature. Thanks to David McLaughlin, David Hayhoe and Mike Cotes for their enthusiasm and help.

Books / Magazines

Grand Prix Data Book by David Hayhoe and David Holland. Published by Duke Marketing Ltd., Douglas, Isle of Man, British Isles. 1996

Autocourse, History of the Grand Prix Car 1966-1991 by Doug Nye. Hazelton Publishing, Richmond, Surrey UK. 1992

Benetton Ford by Phil Drackett. The Crowood Press, Swindon, Wiltshire. 1990

Benetton by Alan Henry. Haynes Publishing, Sparkford, Somerset, UK. 1998

Camel Benetton Ford 1992 Media Pack, Jardin PR, Surrey, UK. Courtesy David Hayhoe

Formula 1 News 1992 and 1993, Formula 1 News Ltd., Bracknell, Berkshire, UK.