The year 1909 was an eventful period; the Indianapolis Motor Speedway opened, the first Lincoln Head pennies were minted, and the Great White Fleet returned to Norfolk, Virginia, after circumnavigating the globe. Closer to home, automobile manufacturer Locomobile continued to offer superbly built road machines tailored to affluent buyers of discriminating taste. In business since 1899, the firm had a rocky start, yet quickly moved into crafting state of the art automobiles. The back story of the company reads like a screenplay.

Locomobile started with John Brisben Walker, owner of Cosmopolitan magazine and an entrepreneur. In 1899, while attending a hillclimb competition at Mount Washington in New Hampshire, Walker was impressed with the performance of the Stanley brothers’ prototype vehicle. Powered by steam, the car’s abundant torque gave it the edge on steep grades. Within days, John Walker was in the Stanleys’ Watertown, Massachusetts, shop with an offer to buy half the company. The brothers declined the offer. Two months later, Walker was back, now wanting to purchase the entire firm. Another refusal, but Walker was persistent. The brothers conferred in a corner of the shop, then presented Walker with a number—$250,000 in cash. To their amazement, Walker agreed. He paid them $10,000 to seal the deal, then he scrambled to raise the rest of the money within ten days.

As the ten-day period was drawing to a close, Walker was having no luck with potential investors. He spoke with a neighbor, Amzi Lorenzo Barber, a millionaire who had made his fortune in the asphalt trade, and convinced him to invest in a 50 percent stake in the Stanley business. The name was changed to Locomobile, a contraction of Locomotive and Automobile. Stanley’s car exuded a train-like aura, with the pistons and connecting rods tied into the rear axle, and the wisps of steam swirling around. Named the Locomobile Company of America, the Stanley brothers were kept on as consultants and to improve the car.

Unfortunately, within a few brief months, Walker and Barber’s relationship soured. They agreed to split the company in half, with Walker moving his half to Tarrytown, N.Y., while Barber stayed at the Watertown location. Walker dropped the Loco name from the car’s title, simply calling it a Mobile. His car was essentially a Stanley Steamer wearing a Mobile label, but sales were dismal, with only 600 cars sold in 1902, forcing the firm to shutter its doors, and Mobile slipped into history.

On the other hand, Barber’s Locomobile company had better luck. Bringing in his son-in-law, Samuel Todd Davis, as company treasurer in 1900, Barber was able to ramp up to full production almost immediately. The steam-powered cars were popular, and by 1902, 5,200 automobiles had been sold. This lofty number put Locomobile at the top rung of manufacturers in the United States that year. With this success, a 40-acre plot was purchased in Bridgeport, Massachusetts, and a new plant was built. Yet Davis could see the writing on the wall regarding future interest in steam-powered automobiles. Davis knew that the key to a viable future lay in gasoline-powered engines. He conferred with his father-in-law, and soon thereafter the decision was made to step away from steam. Davis sold the rest of the steam car firm and the Stanley patents back to the Stanley brothers for $20,000, but the sharp drop in sales forced Locomobile to look for funding to stay solvent. Barber approached his brother-in-law, J.J. Albright, and explained that Locomobile’s future lay in gas-powered models. Albright agreed to inject the needed funds, becoming the company’s major stockholder. Davis became, at age 29, the president of the company. All Locomobile needed now was a car to sell. Davis had a secret weapon, however, a brilliant mechanical engineer by the name of Andrew Lawrence Riker.

Commonly known as A.L. Riker, he had built, in 1884, an electric car at the tender age of 16. Two years later, he earned a patent for a two-cylinder gasoline engine. At 20, he created the slotted-armature motor, still in use today. In 1902, Davis hired Riker as vice president in charge of engineering, and on November 2, 1902, the first four-cylinder gasoline-powered Locomobile was delivered to its new owner in New York City. This car, a 12-horsepower Model C vehicle, was priced at an incredible $4,000!

Locomobile was never a company to shy away from self-promotion, as evidenced by some of the company’s advertising tag lines. “The Greatest American Car” and “Best Built Car in America” attest to a level of confidence in the firm’s wares. The company pursued the high-end market, eschewing mass-market transportation. In 1906, Locomobile built, at a cost of $20,000, a racecar to compete in the prestigious 1908 Vanderbilt Cup automobile race. With a 1,032-cubic-inch engine that generated 120 horsepower, this racer took the checkered flag to become the first American car to win the race, a feat that created considerable positive exposure for the Locomobile brand.

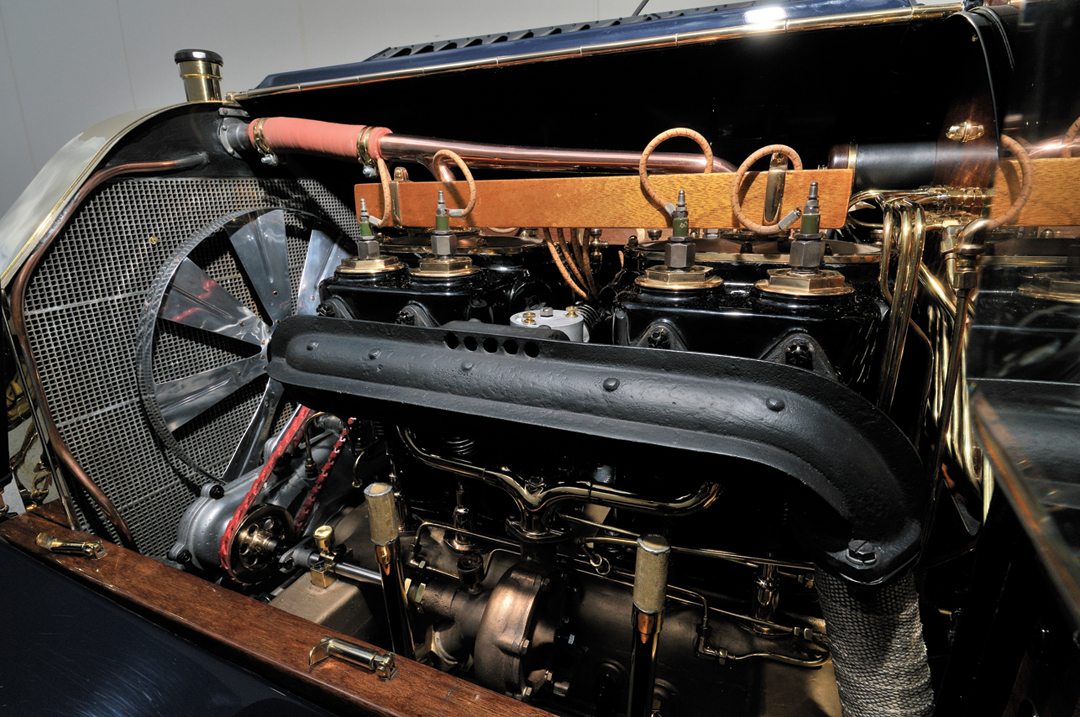

Over the next few years, continuous improvements were introduced in the Locomobile line. Horsepower steadily rose, and appointments were ladled on. By 1904, power output had risen to 22 horsepower, and by 1909, the year our feature car was built, the engines were rated at 30 and 40 horsepower. Featuring a T-Head design and four cylinders, this engine was advanced for its day. With the intake valves on one side of the head, and the exhaust valves on the other side, separate camshafts were required. This design was employed to limit cylinder detonation, or knocking, by using cooling water to envelope open alcoves adjacent to the combustion chambers. While they lowered compression ratios, and subsequent power, controlling knock improved engine reliability.

Locomobile was the last automobile manufacturer to employ this head design on a street car, but the design soldiered on into the 1950s in fire trucks, heavy equipment and some large trucks.

Locomobile continued to build superlative vehicles as WWI broke out. Riker trucks, designed by the company’s chief engineer, were well-regarded, and as the United States started supplying the Allies with trucks, Locomobile ordered massive amounts of material with which to build the vehicles. Unfortunately for Locomobile, Samuel Davis died of a stroke in 1915, and without his steady hand, the company became somewhat rudderless. When the war ended, the expected economic boom failed to appear, and Locomobile was in a huge financial bind when the banks started clamoring for payment on the loans used to finance the expansion. J.J. Albright decided to sell the company to Mercer. Led by Emlen S. Hare, Mercer exercised its option to buy 100,000 shares of Locomobile stock in 1919, thus taking over the company.

The company broke away from Hare in 1921, becoming an independent company once again, but predator William Crapo Durant, yet again booted from General Motors, had formed a new company called Durant Motors, and with a group of investors, bought Locomobile for one million dollars in cash and bonds. Durant Motors did little to update the Locomobile line mechanically, and as the 1920s wore on he introduced a more downscale line. Sales, however, continued to soften, and when the stock market crash of October, 1929 hit the country, Locomobile was forced to close.

Locomobile was one of the standouts in America’s early days of automobile production. By aiming high, the company created vehicles second to none, but the demise of its president, and subsequent questionable decisions by the company’s leaders, put the firm in an untenable situation. During Locomobile’s glory days, however, there were few automobiles that could hold a candle to it.

Behind the Wheel

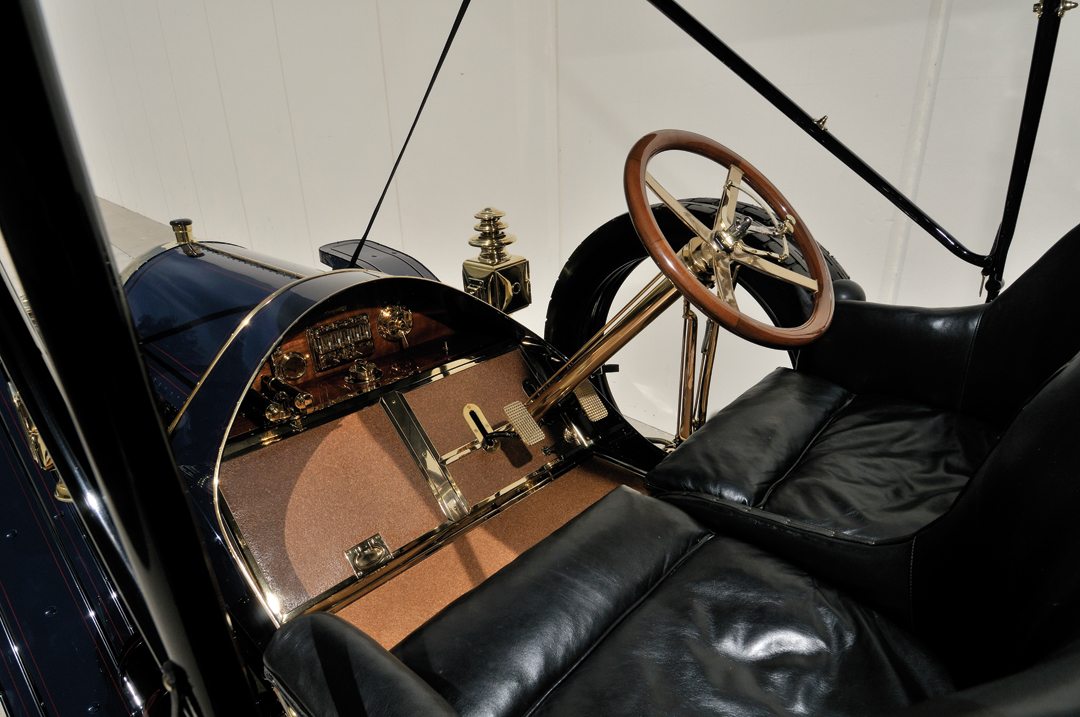

This stunning example of the Locomobile craft is a 1909 Model 40, Type L Toy Tonneau. Built on a beefy 123-inch wheelbase, this brass-era beauty has the larger-output, 40-horse engine, displacing 471-cubic-inches. It rides on wooden, artillery-style wheels, with the rear wheels being motivated by chain drive. Like many cars of the era, it is a right-hand drive vehicle—left-hand drive cars wouldn’t gain in popularity until Ford’s ubiquitous Model T. Cars of the early years of the 20th Century are labeled brass-era for a very good reason; brightwork of the day was polished brass, and lots of it. Prior to our photographing this Locomobile, a crew worked for days polishing the brass to like-new condition.

When I arrived at the Locomobile, I was surprised by the sheer size of the vehicle. With its long wheelbase and huge tires, the Locomobile covers a lot of real estate. Roads of the day were often dirt paths, and considerable ground clearance was mandatory. Thus, the passenger floor was high, followed by the seats. Add the huge folding top, and the result is a huge machine with a huge presence, but the proportions are superb. Everything is in visual balance. As I walked around the car, I immediately noticed the incredible attention to detail. At a time when the average American home cost $1,500, this automobile cost a staggering $5,000! This was a car for only the very well-heeled, but they got a lot of car for their money. Top-shelf leather covers the seats, which feel more like overstuffed armchairs than a basic seat. A considerable amount of wood is used, such as the steering wheel, floorboards, dashboard, firewall and trim. Any metal on the car is sculptural in beauty and substantial in feel. This is a machine built to last.

Automobiles of this era don’t come to life quite as easily as modern cars. Setting ignition spark, the gas lever on the steering wheel, and a host of other prerequisites must be attended to before a strong back is put upon the starting crank. This Locomobile, however, is in perfect condition, and once a touch of prime is used, it takes but two quick spins of the crank and the big four-cylinder comes to life. It’s a comforting, mechanical sound, and it’s readily apparent that there is a lot of metal going up and down in those cylinder bores! Feeding in a touch of throttle excites the engine, which responds with an increase in frenetic sound. It’s also clear, though, that this engine is not a high-rpm power plant; what it generates is massive torque.

Behind the wheel, the visibility is unmatched. Of course, the lack of a windshield and doors helps. The hefty, wooden wheel has a satisfying feel, like the helm of a big boat. I push the clutch in, move the huge gear selector lever firmly into gear, and let out the clutch while I tickle the throttle. With a slight shudder, the big four-cylinder pulls the vehicle into motion. Soon, very soon, it’s time to grab second, and with a quick stab of the clutch, I slip the shifter into neutral, let the clutch out, then depress it again, move the shifter into second, then let the clutch up. Cue more wind in the face. But it doesn’t affect the smile on my face.

The steering is firm, direct, and quick. It’s clear to me that driving on the road of the day, for any considerable distance, would have required substantial upper body strength. The tall, narrow tires tend to have a mind of their own about their path, and a firm hand on the wheel is needed to keep them pointed in the desired direction, but the feedback through the wheel is wonderful, almost alive. The throttle responds like a tractor, all low-end torque, deep exhaust rumble, and chain-drive rattle, but it all comes together in a polished, refined fashion. I can now understand why Locomobiles were held in such high esteem. The automobile drives years ahead of its build date.

Closing in on a curve I throttle back, and the engine brings the speed down quickly. I push the clutch in, grasp the outboard brake handle, and ease it back. The rear brakes, connected to the lever by cable, do an effective job of shedding speed, and soon I push the brake lever forward, releasing the brakes. I then release the clutch while I twist the steering wheel. The nose carves around the corner and I’m accelerating again. A long stretch beckons, so I slip the gear lever into third and ease the throttle lever up. The engine pulls strongly, and I’m soon making a 30 mph hole in the wind. The straight axles bounce over road irregularities, but keeping the Locomobile pointed down the road is surprisingly easy. This was a gentleman’s transport, and the quality and engineering show.

This example won Best in Class at the 2010 Concours d’Elegance of America at Meadow Brook, and will be offered for sale at the 2013 Mecum Daytime Auction at Monterey, California, August 15-17.

SPECIFICATIONS

Wheelbase: 123-inches

Length: 181-inches

Width: 64-inches

Cylinders: Inline-4

Eng. Displacement: 471-cubic-inches

Bore: 5-inches

Stroke: 6-inches

Engine output: 60 HP

Gears: 4 forward

Tires: 36 x 4 (F), 36 x 4.5 (R)

Fuel Capacity: 18 gallons US

Brakes: Drum, rear wheels