Photo: Ian Welsh

It can’t be denied that the world of motor racing, both contemporary and historic, is saturated with egos. Some would say that it’s all really driven by egos, and that is sometimes directly connected to the size of the wallet. Perhaps without such egos we wouldn’t have motor racing at all.

So egos are certainly important, but there is something else that’s behind so many involved in motor racing and, in particular, historic motor sport. I am referring of course to the passion that many have for the sport. A passion that is so strong in some that it outweighs the need for podium finishes and is certainly far stronger than whatever shekels may influence others.

Once such person who has most certainly been driven by passion is Bob Britton of Sydney, Australia. Britton’s name may not be familiar to many outside that continent, but some will know the Rennmax marque of racing cars that he commenced building in the early 1960s. Looking back now, at the last half century or so, Bob Britton would have to be one of the most unassuming of all racing car manufacturers, not only in Australia, but probably worldwide. Never one to draw attention to himself, Bob could wander the pits of any circuit in Australia and be completely anonymous. Thankfully, in the 21st Century that has now all changed, and his contribution to motor sport is well and truly recognized.

Bob Britton built his first car in the middle of the 1950s, and like so many of his contemporaries from that period it was styled on the successful air-cooled Cooper. At the time, Bob was employed by a Sydney-based heavy machinery manufacturer and didn’t even have a lathe or bench grinder that he could call his own. However, that didn’t deter him as he used to drop in on friends to use their equipment. Understandably, Bob wasn’t the only person who would “drop in,” and he soon met up with the likes of Ron Tauranac, who later went on to design and build the Brabham and Ralt ranges of competition cars.

By 1960, Britton found himself involved in so much motor sport fabrication that he started to consider self-employment. In an interview Bob gave to the late Graham Howard in 2002 he said, “I realized that if I built a couple of wishbones a week, it would pay for my board.” Seems like a pleasant way of earning a living, but his expertise was about to be recognized.

Photo: Ian Welsh

First Rennmax

Move on to 1961 and the motor sport world was being introduced to the delights of the new Formula Junior classification of racing cars. In recognition of Bob’s skills at fabrication, it was suggested to him that he should have a go at building a Formula Junior. At the time there was a father and son team, Ossie and Noel Hall, and it was Ossie who suggested that son Noel could do well in a Junior. At the time the Halls were running a “Highline” Cooper-Climax 2.2-liter, but before Bob had a chance to light up his welding torch, the enthusiastic Ossie Hall had a change of heart.

According to Britton, Ossie stated, “Why stuff around with a Junior, let’s build a real car.” So was born Rennmax Engineering and the first Rennmax racing car, with the name being an amalgam of the German word Renn, meaning race, and the abbreviation for maximum.

This first Rennmax combined the engine from the Halls’ Cooper-Climax, as well as the gearbox, brakes and wheels. Britton built a one-off chassis that was along the lines of a Lotus 21, but with specifically cast rear uprights to his own design. The car ran well with an 8th place in its first outing on the Mt. Panorama circuit at Bathurst over Easter, 1962, driven by Noel Hall. Just two months later, it carried Hall first across the line to win the NSW Road Racing Championship at Catalina Park in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney.

The days of Bob dropping in on friends to use their machinery were soon fast receding, but the contacts earned during those days were invaluable. It was 1962, and one such contact had recently bought a new Lotus 20 Formula Junior and, in what was probably insurance for the future, asked Bob to build a new chassis as a spare. Of course, such an exercise required the making of a jig, which Bob made incorporating the alterations Lotus had introduced with the Lotus 22. This was done using the recently imported 22 of Leo Geoghegan as a guide.

Photo: Ian Welsh

Welding Tubes

Meeting Bob Britton for the first time is quite surprising as he certainly comes across as a bloke who shuns the limelight. In his interview with Graham Howard, he described himself as someone who would be more than happy “just being Joe Blow, welding tubes in my back yard.” However, as much as Bob would have preferred less notoriety, the days of making a few uprights a week were very much behind him.

The jig made to build the spare Lotus chassis was very quickly put to good use with six to eight cars soon following. Yes, I am being a little loose with the numbers, as Bob never kept a record of every car built. Over the years Britton built close to a hundred cars, and while each wasn’t numbered, he does recall each through the name of the person who originally bought it. Each of these cars were titled as a Rennmax and were not just chassis, but also included all the suspension components and wheels.

Unfortunately, Britton wasn’t much into giving his cars model descriptions either, but this first batch of cars went on to be known as the BN1 series. No, it’s not a name given to the cars by Bob, but probably invented some years later by a well-known Australian racing driver by the name of Bob Muir who clearly had his tongue firmly planted in his cheek. BN stands for “Britto and Nooj,” with the former being a straightforward nickname for Bob Britton and the latter being that widely used for local aluminum wizard Stan Smith, who was undertaking work for Rennmax.

Today the BN titles seem to be more widely used than in period, with the BN1 given to the first cars based on the Lotus 20-22 designs, through to the BN7 which was the Australian Formula Two car of the mid-1970s. However, just to confuse the matter further, the BN6 designation, while used for the prototype BN7, is also used for a sports racing car!

Matich

It was at this time that apart from building cars under the Rennmax name that Bob Britton was called upon to assist such well known Australian competitors as Frank Matich and Alec Mildren. Matich had yet to move completely into open-wheelers and was running an extremely successful Lotus 19 sports racing car, which evolved over time to stay in front. Bob did the work, and by the time it was finished he had virtually changed the rear end to be more akin to a Brabham than a Lotus. Bob also did the work on Frank’s later Brabham BT7 to drawings that Ron Tauranac sent over from England. Bob also built a Lotus 23-like sports car for Alec Mildren that was to see service fitted with a 2.9-liter Maserati engine.

At the other extreme Bob built his first Formula Vee in 1965, the first of which was called the CB, but they proved to be so successful that they were all renamed Rennmax.

Britton’s and Frank Matich’s paths crossed once again when, during 1966, Bob was asked to make modifications to the newly acquired Matich Elfin 400 sports racing car. That evolved into Bob building the chassis and suspension for Matich’s own SR3 series of sports racing cars and resulting in Britton going with Matich to the U.S. to compete with the SR3 in the 1967 Can-Am series.

Formula 2

While Britton was in the U.S., a Rennmax loosely derived from a Lotus 22 and driven by Max Stewart, won the 1967 Australian Formula Two championship. The following year Stewart repeated his success by sharing the championship with Garrie Cooper’s Elfin.

Further Australian Formula Two successes followed for Max Stewart, who was then driving for the Alec Mildren team. The two, three or four cars Bob Britton built for the Mildren team were based on the Brabham BT23 chassis. In Stewart’s hands, one of these cars powered by a Waggott two-liter engine (then known as the Mildren Waggott) was still successful in 1971 when he won the CAMS Gold Star. This same basic chassis design would go right on winning with other drivers and such diverse engines as the 2.5-liter Climax and even a flat-8 Porsche.

In addition to the SR3 series of cars Britton built for Matich, he also built quite a number of sports racing cars for various other customers. While some were badged as Rennmaxes, others carried the customer’s name. One such car was built for Lionel Ayers that was fitted with a five-liter Repco V8 and proved to be very successful during the 1970s.

That same decade brought a string of successful cars in both the Formula Two and Vee genres, but the writing was on the wall to a great extent for traditional Australian motor sport when there was a change in direction toward touring car racing. As it continues today, the attraction of sitting on the couch watching sedans race proved to be irresistible to the average Australian racing enthusiast.

Bob Britton saw the same writing, and after nearly 20 years of making racing cars for customers who at times could be demanding, he sought other employment. However, that didn’t stop him from continuing to weld tubes together in his spare time as a hobby. Today, Bob Britton continues to “weld tubes” and finds himself in demand for advice on the many cars that he built over the years. Bob’s level of expertise and good nature is also held in very high regard by the Australian historic fraternity, and he is a frequent invitee to race meetings. In 2002, the Historic Sports and Racing Car Association paid due respect to Bob by holding their Eastern Creek race meeting in his honor, with the program cover featuring the range of Rennmax cars drawn by well-known motoring artist Brian Caldersmith.

While always wanting a low profile, Bob Britton in 2000 was awarded the Australian Sports Medal with the citation “Constructor Rennmax open wheel race cars. Aust F1, F2, FF, FV – Title-winning cars 1961-2000.” The Australian Sports Medal commemorates the efforts of Australians who have made their country a nation of sporting excellence.

Photo: Bob Britten Collection

The Rennmax Palliser

As mentioned, the Rennmax name is well known in Australia so when the opportunity arose to get behind the wheel of one, it was something not to be missed.

Owned by Chad Wheeler from the Australian state of Queensland, this car is known as the Rennmax Palliser. It was sold originally to Alec Mildren in 1969 as a spare, but not used. Occasionally working for Mildren at that time was Don Baker, who also held down a full time job as a flight steward with QANTAS. Baker acquired the car for work he had done and during one of his trips from England brought back with him Palliser uprights and steering, which were fitted to the car.

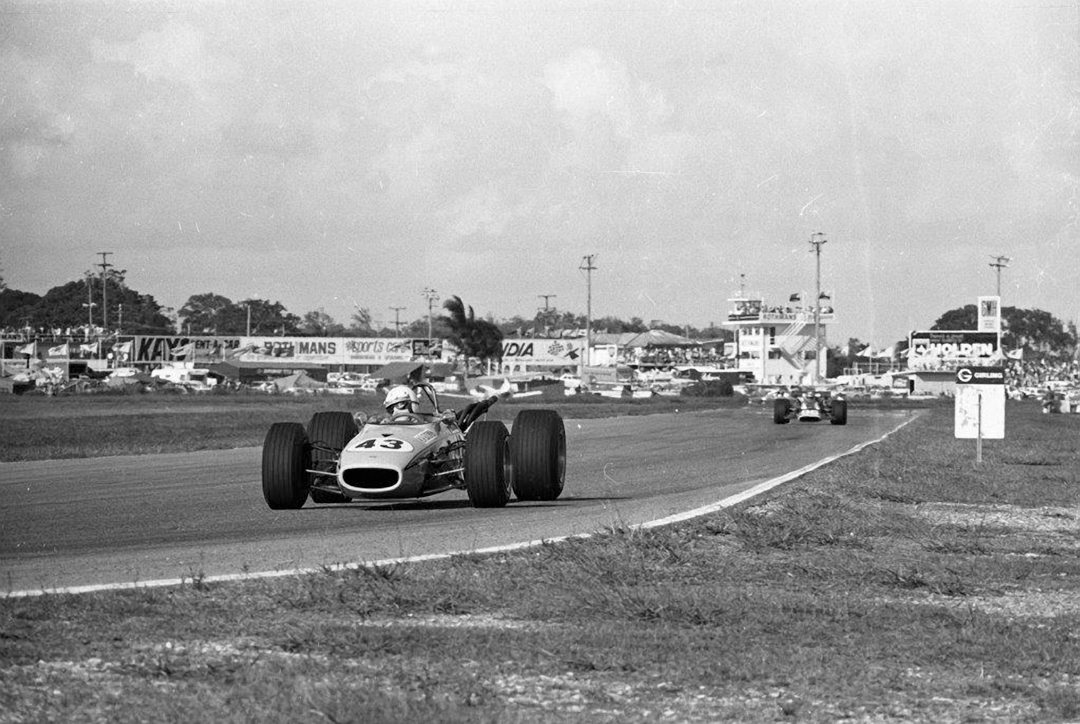

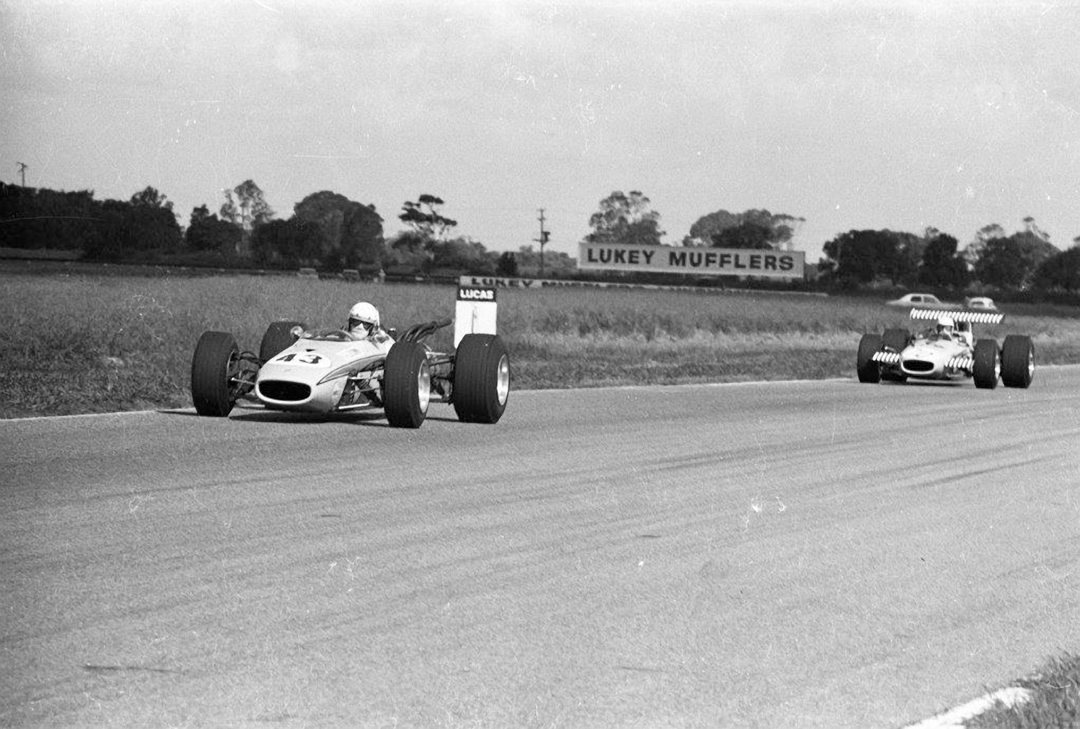

Fitted with a 1600-cc DOHC Ford engine it was run in the 1970 Tasman race at Surfers Paradise and also in the Australian Gold Star championship of the same year. Through to 1975 it passed through a number of hands and was raced without any notable success at such diverse circuits as Warwick Farm on the outskirts of Sydney and Lakeside in Queensland.

In 1975 it was sold to Malcolm Brewster who altered the car’s appearance somewhat and converted it into a Formula Three car with a 1,300-cc Ford pushrod engine. Fortunately, Malcolm is still very much involved in historic motor sport and we managed to catch up with him for a quick chat about the car.

Photo: Bob Britton Collection

“That was a great car,” Malcolm answered when I tested his memory. “I was coming out of sedans, Minis and the like, and wanted a go at open-wheelers. Formula 5000 was very much on the wane within Australia, but something like Formula Three sounded really attractive. So I bought this car from David Booth who had fitted it with a 1300 Ford engine. It had a chisel nose and a cockpit surround from an Elfin 600.

“I knew Rennmax, having worked for Bob Britton for a time so it seemed like a good step forward for me. I ran it at both Oran Park and Amaroo Park during the middle ’70s and in particular in the Goodyear F3 Series that was held at every Amaroo meeting. Finished in blue with gold lettering and striping it was a good looking car. Thinking back, even if it was an eight- or nine-year-old chassis it was still very much up there with more modern cars of the period. It’s good to see that it’s still being used and enjoyed.”

Chad’s Words

Like many of us, Chad Wheeler who owns the Rennmax Palliser, was greatly influenced by his father and his interest in Speedway. Chad started out in karts and, like father like son, moved into Speedway midgets. However, over time he started to lose interest in Speedway and turned to circuit racing and, in particular, open-wheelers. To satisfy his wish to get into circuit racing, Chad bought the Rennmax Palliser in 1999.

“I’m not too sure who owned the car after Malcolm,” Chad said. “However, in 1983 it was purchased by John Allison, who raced the car in historics until 1990 when he tragically crashed the car at Amaroo Park and subsequently died as a result of his injuries. The car was understandably quite a mess when it was purchased by Laurie Knight.

“I bought it from Laurie,” Chad added. “It was almost in two pieces as a result of John’s accident, and as far as I could work out it had sat under a carport for close on to ten years and, while not directly affected by the weather, it was in poor condition. After I made contact with Laurie and made arrangement to buy the wreckage I brought it all home in a 6×4 box trailer. I would probably say that it was about 80 percent complete, but very damaged.

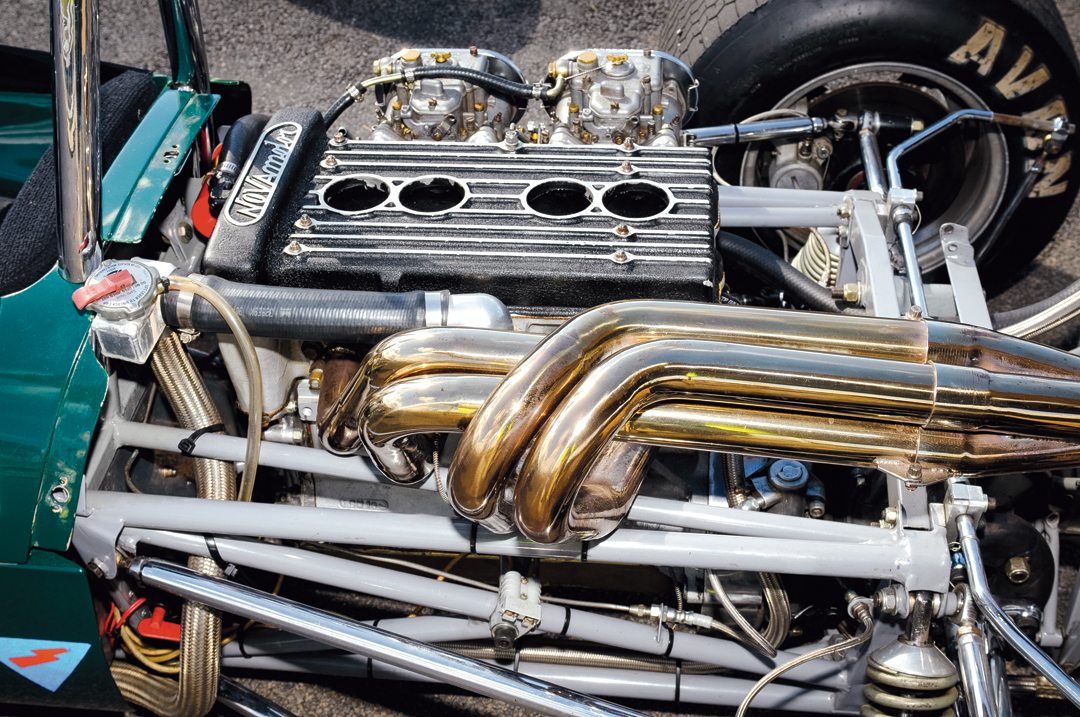

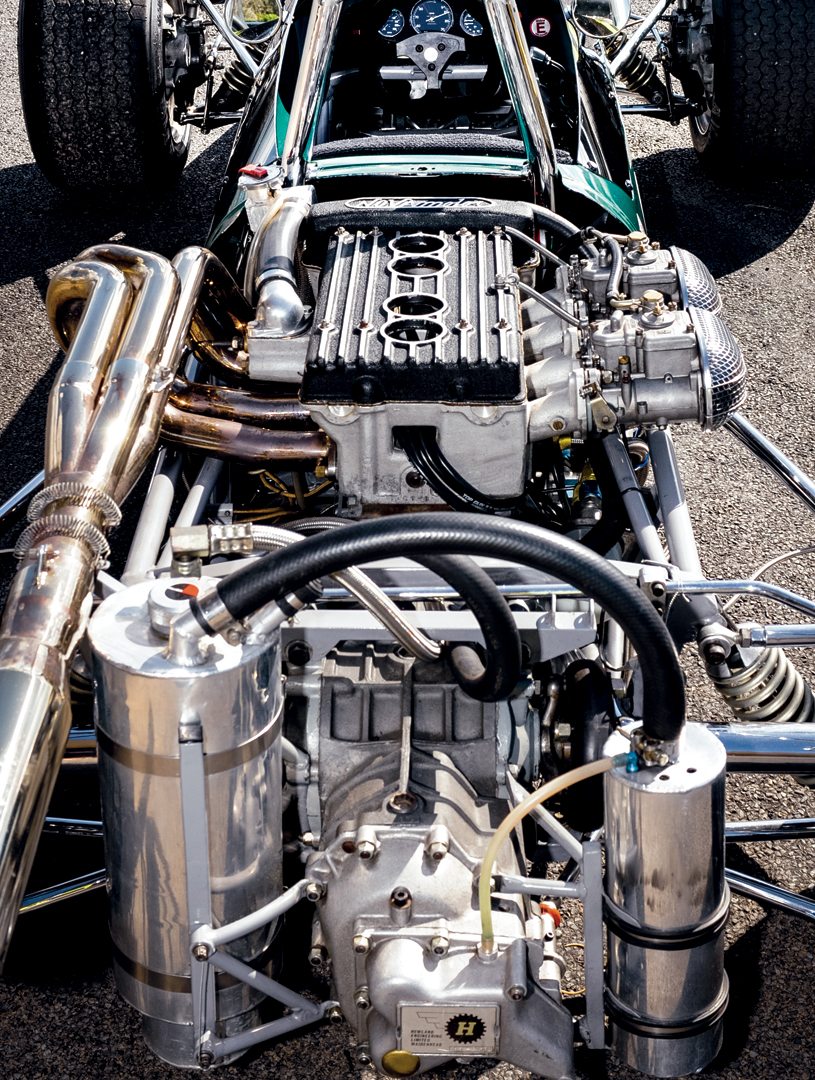

“So we set about restoring the car and had it ready for the 2001 Lowood Sprints. Since then I ran the car at every Speed on Tweed event and such circuits as Phillip Island, Eastern Greek and Lakeside. It’s fitted with a Novamotor 1600 DOHC engine and Hewland Mk5 gearbox.

“Bob Britton was very helpful during the restoration.” Chad noted. “I like to do most of the work myself, plus it helps that I enjoy doing it. I’ve learned so much over the years like rebuilding engines and Hewland gearboxes. Of course, by not throwing bulk money at the car it has meant that it’s not at the front as far as the results go, but I am more than satisfied with finishing in the top five.”

What Bob Said

Always keen to go right to the source, I thought a word with Bob Britton wouldn’t go astray. In typical Bob Britton style he said that off the top of his head he couldn’t recall every car he built, but certainly recalls who he made them for. I mention to him that I had been told that the car belonged to Alec Mildren and followed by Don Baker. Surprisingly, Bob reached for his business card folder and pulled out the card for Don Baker.

“I was going to check up, before I open my mouth,” Bob said in response to my first question. So Bob gets on the phone to Don Baker who is still involved with racing cars and finds out about the early history of Chad Wheeler’s Rennmax Palliser. “There you go straight from the horse’s mouth. Alec Mildren bought a spare chassis from me. I had forgotten how many Alec had bought from me as he was running a couple of cars. I forget how many I made for him, but he bought a spare just in case. Anyway, Don Baker used to go out and help the Mildren team. Don wasn’t actually employed, but they did a deal that Alec gave him the chassis in lieu of all the work he had done for the team. Don got a set of wishbones from me, and then he got the Palliser uprights and wheels from the UK and then bought a Vegantune engine. Then he put it all together and sold it on to Bob Johns as a complete and running car.”

I then mentioned to Bob that Mal Brewster had the car for a time and ran it as a Formula Three. You could literally see the lights go on when he said, “That’s right; it all comes back to me now that you mention Mal. He bought it from David Booth and I have a photo of the car taken at Amaroo Park.” Then Bob reached behind a drawing board and pulled out a photo of Mal Brewster going down the hill at Amaroo Park.

“The last time I saw the car was when it was running at Speed on Tweed when Chad was pedaling it quite well. I remember thinking the first time I saw it at Speed on Tweed that they had done a beautiful job of putting it back together. No way did I ever make them that good when they were new.

“Looking back at the cars that I built over the years, I really wish I had taken down more details of each one, but I was busy with people coming and going, as well as raising a young family of three kids with my wife. You’d think it would go on and on, you don’t look too far into the future and working in a crazy industry of building racing cars that got to me in the end that I had to go and get a job. Thinking about it all now, who would have foretold the historic scene? I was flat out building cars that were virtually disposable items as quickly as I could to keep my customers happy. Now some 30-plus years later when someone asks me about an individual car, it’s bloody difficult remembering! However, I certainly don’t regret doing it, and today I feel the same as what I did when I started off in the 1950s when a bunch of us started out building 500-cc cars.”

At Lakeside

We were at the Lakeside Park Circuit on the outskirts of Brisbane, the capital city of the Australian state of Queensland. Lakeside first witnessed competition in 1961 and it wasn’t long before it hosted such events as the Australian Grand Prix, the Tasman Series and numerous race meetings featuring GT, sports and touring cars. However, encroaching suburbia and financial problems caused the circuit to close temporarily in 2002, but it wasn’t long before some local government officials realized the amount of money the circuit had been attracting to the area and, following a major rebuilding and an influx of local support, it reopened in 2009. Lakeside Park continues to thrive and, apart from race meetings, has become a popular gathering area for local car clubs.

I have often found that open-wheel racing cars are built with a view of going as fast as they could without giving a thought to the comfort of the driver. Sure there is no point sitting in a lounge chair with your feet up and expecting to win a race, but similarly there is also no point making the driver feel so uncomfortable that he/she spends more time worrying about their left leg about to be cut off at the ankle by the clutch pedal than concentrating on driving.

So I walked up to Chad Wheeler’s Rennmax and was rather taken aback at the particularly large fire extinguisher that I had to slip my legs over before I could even get into the car. But not to worry, as like so many cars, it was a simple matter of standing on the seat and letting my legs slide forward until they could go no further. So far so good! I must admit that I did find it quite a pretty car with clean simple lines and beautifully presented.

The main Lakeside straight finishes with an interesting sweeping right-hander that’s also uphill. In a lesser car with skinny tires it would be perfect for lots of right rear wheel spinning, but with 12-inch wheels at the back there is little chance of that. Shades of the Karussell at the Nürburgring while I take it in a lazy third gear. I suspect that Chad would be selecting an enthusiastic second when among race traffic. This is followed by a slight left-handed bend that honestly I didn’t think the Rennmax even noticed. The Bus Stop left-hander comes next, and it’s much longer and so I’m now into fourth. More left-handers follow including a longer one that’s also slightly uphill, the last of which is called Hungry Corner, the name of which no one has ever been able to explain. That’s followed by a long sweeping right that’s downhill. I’m in third going through and then quickly up into fourth, but there is no one else around and I suspect that with a little red mist rising, third could be held far longer with fourth selected just before the circuit swings right into the start of the straight. Not far along the straight, fifth is chosen and then it’s back to the Karussell.

With a few more laps under my belt I was soon really enjoying the experience, especially as I found that no part of my anatomy was being impacted upon by a protruding chassis tube, and my right foot didn’t have to be contorted into an unnatural angle. Yes, I was comfortable and I found it a very easy car to drive. I could quite happily get used to this!

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis/Body: Tubular steel chassis and fiberglass body

Wheelbase: 7 feet 7.66 inches (2,350mm)

Track: 4 feet 5.86 inches (1,420mm) F – 4 feet 8.29 inches (1,470mm) R

Weight: 923.90 pounds (419 kilograms)

Suspension: Front: Independent with coilover shock absorbers, anti-roll bar, Rear: Independent with coilover shock absorbers, anti-roll bar

Steering Gear: Palliser rack and pinion.

Engine: Novamotor twin-cam 1,600-cc

Power: 180hp at 7,500 rpm.

Carburettor: Twin Weber DCOE 45mm

Clutch: Single-plate

Gearbox: Hewland Mk5

Gears: 5 forward, 1 reverse.

Foot Brake: discs all around

Wheels: Palliser 10-inch front & 12-inch rear

Acknowledgements / Resources

Many thanks to Chad Wheeler for the opportunity of getting up close and comfortable with his Rennmax Palliser. Thanks also to Lakeside Park for the track time, and extra special thanks to Bob Britton for bringing to us all the Rennmax range of competition cars.

Bathurst – Cradle of Australian Motor Sport, John Medley, Turton & Armstrong ISBN 0 908031 70 X

Historic Racing Cars in Australia, John Blanden, Turton & Armstrong. ISBN 0-908031-83-1