There is something very special about a Bugatti, and this example is very special indeed. Highly original, this race winner from the 1925 season has lived nearly all of its life “down under” in Australia, and has only recently found its way to Britain, where one of its sister cars was last raced at Brooklands in 1926 by the king of speed himself, Sir Malcolm Campbell.

MONTLHÉRY SUCCESS

Photo: Mike Jiggle

Chassis 4604 is a true survivor from the golden age of motor racing. This car is one of five works Type 39s built by the famous company founded by Ettore Bugatti, and the cars only raced in two events before being sold off by the factory. For the 1925 French Touring Grand Prix, at the then recently extended Montlhéry Grand Prix circuit near Paris, Bugatti took the decision to enter his Type 39 cars. He believed his Type 35 cars would not be competitive against the Alfa and Delage cars in the last full year of two-liter competition, and so modified Type 39s were seen as the marque’s best bet for success in this race.

The Type 39s were converted to touring specification, with full road-going modifications made to meet the race’s regulations. The event required cars to carry full road equipment, including lights, full wings, a hood and a self-starter. Ballast was even carried to simulate the weight of a passenger. Short-stroke 1500-cc 8-cylinder engines were fed with a single Solex carb, and as mid-race refuelling was not permitted, enlarged tanks were also fitted. Bugatti felt victory was within his grasp, and he was right.

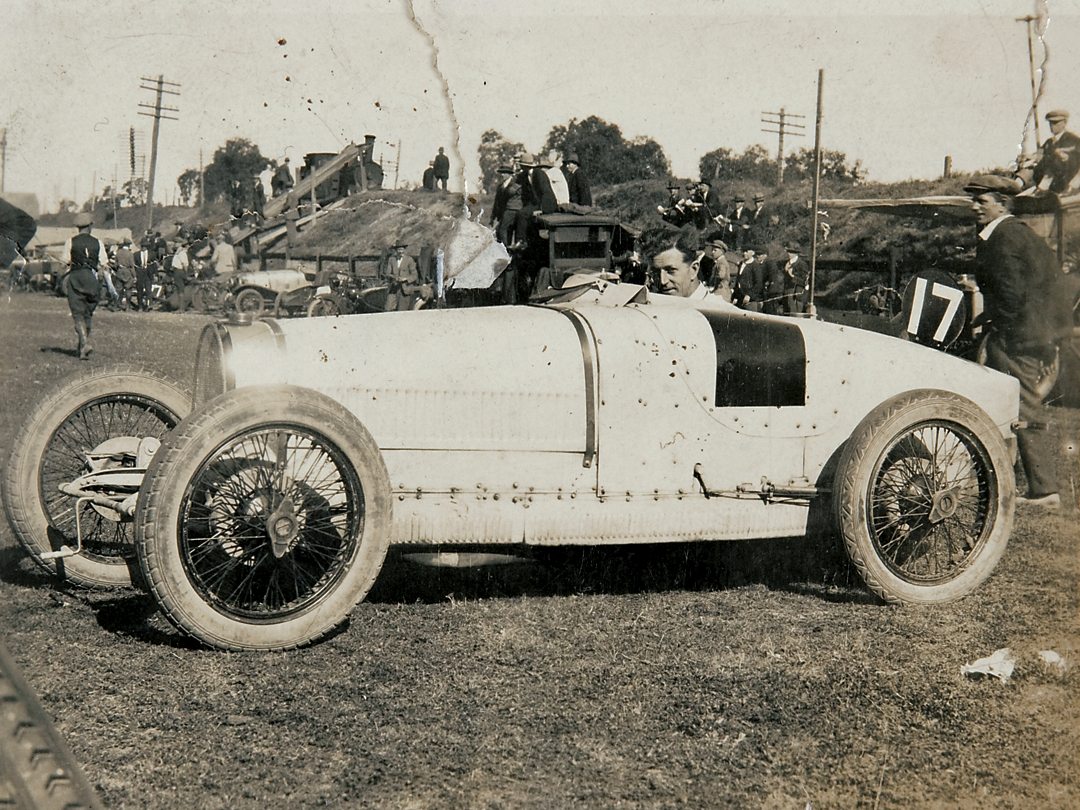

Five Type 39s were entered, and the factory cars would be driven by brothers Pierre and Ferdinand de Vizcaya, Giulio Foresti, Jules Goux, with 4604 driven by Bartolomeo “Meo” Constantini. Such was Bugatti’s belief in success at Montlhéry that his cars and drivers were presented to crowds the day before the race in Strasbourg’s Place Kleber. Bugatti himself was keen to see one of the sport’s earliest team launches, and turned out wearing a fine suit, complete with a camera around his neck and his white terrier dog at his heel, to watch the cars depart for Paris. As the squad of five drove away, rain began to fall, allowing the car’s road equipment hoods to be firmly tested for the very first time.

With the popularity of motor racing in France on the increase, mainly because of the growing fame of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the Automobile Club de France believed a big crowd would attend Montlhéry. Sadly they weren’t right, and the extra trains and an omnibus pressed into service to ferry the expected crowds from trains to the track remained empty with the grandstands virtually devoid of spectators when the race started. When the flag dropped competitors had to depart without outside assistance. In the cold air the five Bugattis were not keen to start—something we experienced with 4604 on our visit for this profile—but once fired up, all five Type 39s were keen to make up lost ground.

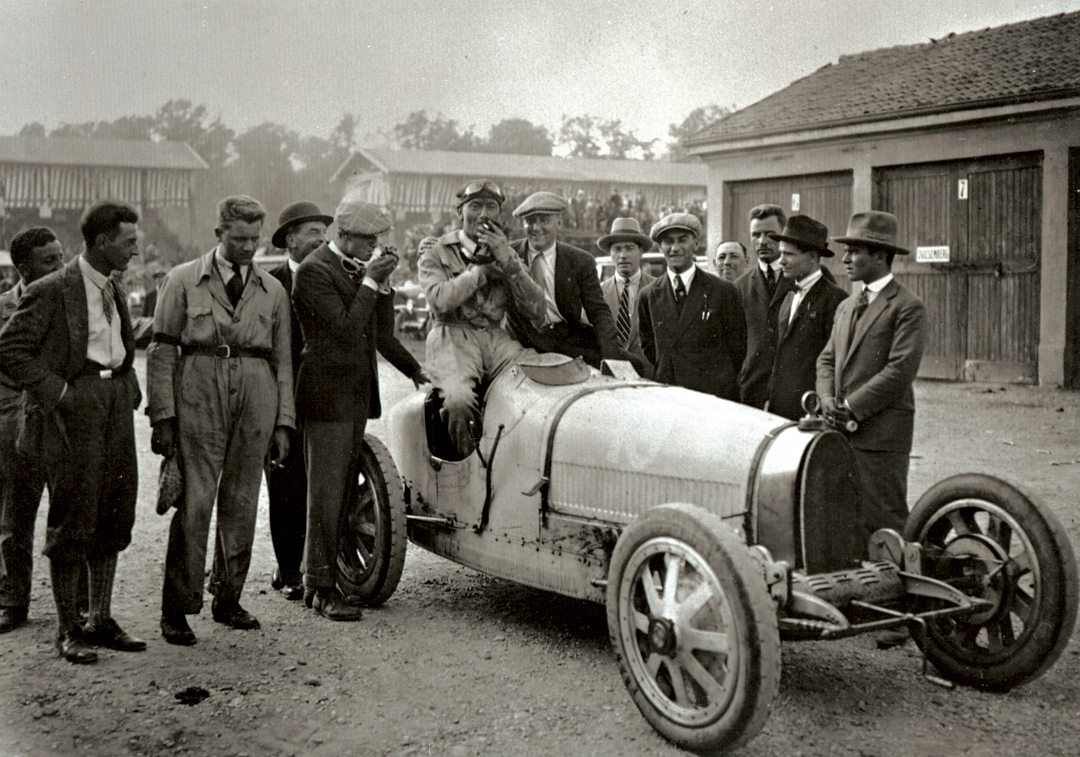

Photo: Mike Jiggle

Headed by Pierre de Vizcaya, the Bugattis made solid progress through the early stages and after a distance of nearly 400 miles Pierre was in 4th position although his brother, Ferdinand, was out with a holed radiator. Some of the other competing cars suffered significant tire wear throughout the race, but the Bugatti machines were not only nimble but light, and the Michelin tires on their aluminium eight-spoke wheels did not require changing. As fellow competitors toiled, the remaining Bugatti squad ran like clockwork, and at the end of the race it was Constantini in 4604 who was crowned the winner. Bugatti cars finished 1-2-3-4. It was a fine moment for Ettore and his eponymous marque.

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ACTION

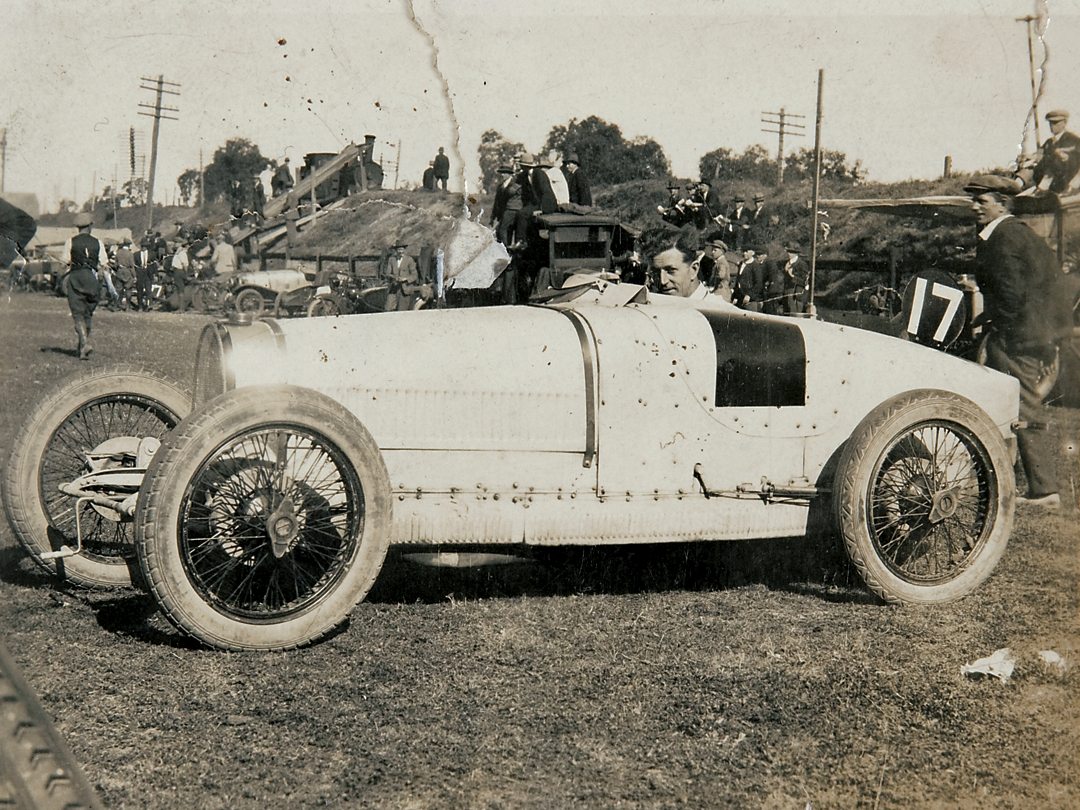

The 1925 Italian Grand Prix was scheduled for the first weekend of September, and in anticipation of the new 1.5-liter regulations for the 1926 season, Bugatti quickly prepared all five of the Type 39s for a trip to the Autodromo Nazionale di Monza. The sportscar-style road-going equipment was stripped and removed, and standard Grand Prix bodies fitted to the five machines that were then duly delivered to the Italian track. All five drivers who had lined up at Montlhéry were again tasked with driving the 1500-cc cars in a race that organizers used to encourage new participants, adopting regulations for the following year’s formula. During the short time that Bugatti had to prepare the cars prior to departure for Monza, the 39s’ engines were uprated with a higher compression ratio and also had twin carburetors fitted to enhance their performance around the temple of speed.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

At the circuit, excitement was growing. Delage, Duesenberg and Italian icon Alfa Romeo were all in with a shot at landing the coveted World Championship crown. Ahead of Monza the three manufacturers had all won a race each during a very competitive season. Duesenberg had triumphed at the “Brickyard,” winning the Indianapolis 500 with Peter de Paolo at the wheel. Alfa Romeo won at Spa-Francorchamps courtesy of Antonio Ascari, and Delage took victory on home soil in France at Montlhéry with Robert Benoist and Albert Divo sharing duties—although it was sadly in this race that Ascari crashed and lost his life.

Monza was billed as the title decider for the 1925 World Championship and the fanatical Italian crowds were set to be treated to a spectacular affair. However, just before the race meeting commenced, Delage withdrew, leaving the title race between just Alfa and Duesenberg. That left just the two manufacturers to battle it out for the title. As the action began, 2500 pigeons were released to fly over the Monza start/finish straight, and massed bands struck up, as the 16 starters roared toward the Curva Grande on the first lap of an event that would last for well over five hours.

Alfa Romeo and Duesenberg fought at the front of the field, but at the end of the race it was Alfa that emerged victorious. Gastone Brilli-Peri guided his car to victory, while Tommy Milton could only manage a 4th for the U.S. Duesenberg team. It was a day that belonged to Alfa Romeo. The hugely patriotic home crowd cheered wildly as Brilli-Peri passed the checkered flag to win and secure the world title for the Italians. Behind, at the wheel of 4604, Meo Constantini drove superbly to reach the finish in 3rd position—a podium placing in 2013 terminology. The three other surviving Type 39s finished 6-7-8, headed by Ferdinand Vizcaya. Of the five Bugattis that started, only the Jules Goux entry failed to make the finish—a ruptured fuel tank causing his demise.

Photo: Spitzley Zagari

On its appearance at Monza the Type 39 had shown great potential as a Grand Prix machine, and during 1926 a car of that type would go on to win World Championship Grands Prix at Miramas, Lasarte and Monza.

HEADING “DOWN UNDER”

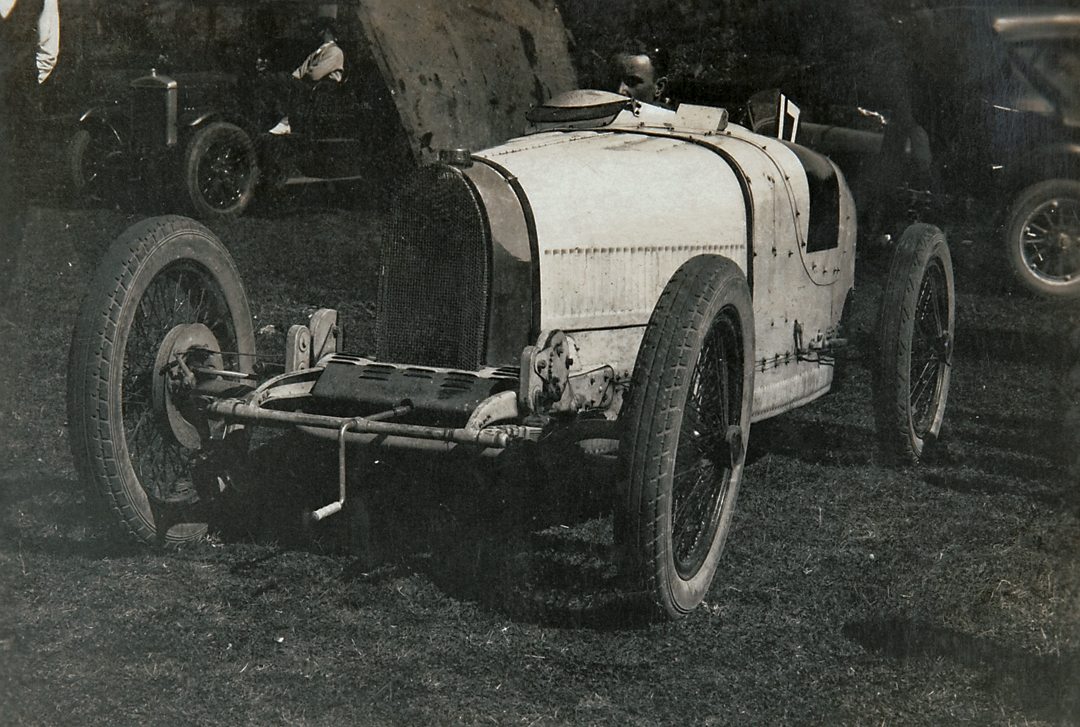

Shortly after the European season ended at Monza, 4604 and its sister car 4607 found themselves sold, and heading via boat to Australia. The two voiturette team cars were loaded and sailed halfway around the world following negotiations that involved Bugatti driver Giulio Foresti. Based at that time in England as a salesman, Foresti played his part well in selling the two cars to keen Australian enthusiasts, having promoted the machines as “Maroubra Brescia Beaters.”

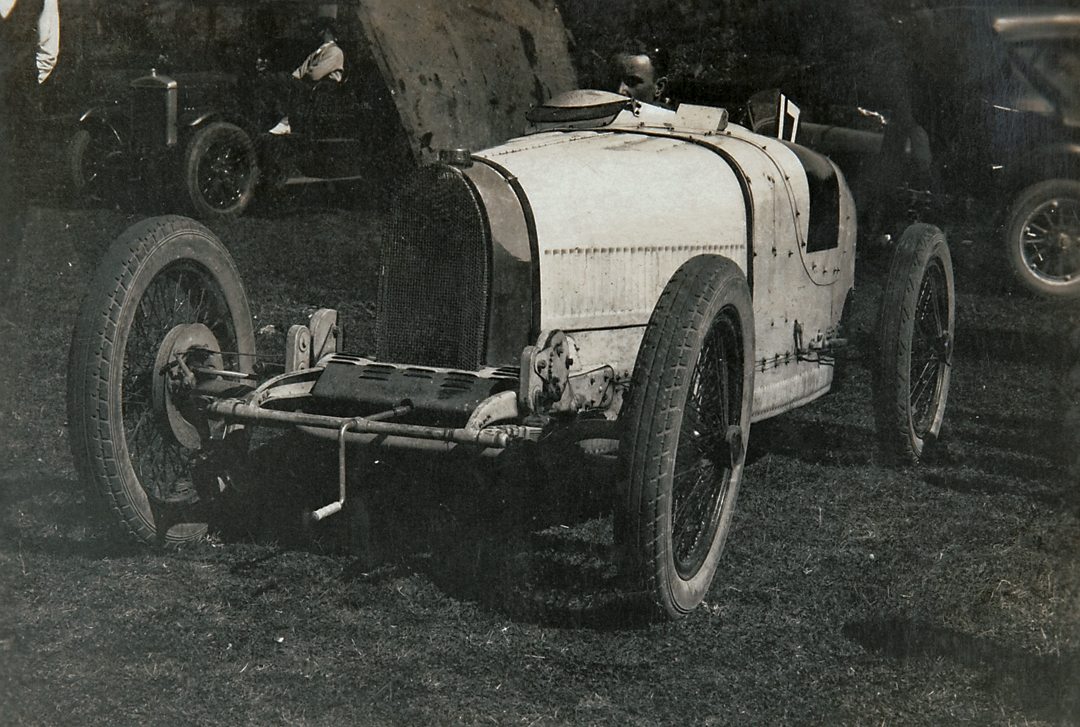

Chassis 4604 was used in an attempt for the Australian Land Speed Record, having been acquired by Frank Parle, a wealthy chemist, and it was also entered by him for driver Jack O’Rourke at Maroubra in June 1926. The car disappointed on its maiden outing, but one month later it was winning at Maroubra when it clocked a winning speed of more than 80 mph.

Photo: Spitzley Zagari

Wheeled out to compete on a regular basis, 4604 was often seen competing in events in both Australia and New Zealand. The car was known to be fast, and indeed was clocked speeding on the public highway at over 100 mph when its then owner, Hope Bartlett, was stopped by the New South Wales police! The car changed hands numerous times during the early to mid-1930s, and with Carl Junker at the wheel was leading the Australian Grand Prix of 1932 when its engine threw a rod. Junker had won the race the previous year at the wheel of sister car 4607.

The car suffered another engine failure in early 1938, and after this mechanical problem 4604 changed hands once more, finding itself under the ownership of Ted Lobb in New South Wales. Lobb loved his Type 39 and carefully preserved its original specification—his doing so allowed the world to retain the only unaltered Type 39 in existence. It remains the only Type 39 that has not been modified away from its 1925 Monza specification, and Lobb’s devotion to the car ensured that 4604 also remained the only unblown Type 39 in the world.

It appeared at a Bugatti rally in Wagga Wagga during 1968, but after that the car was little used. In 2004, 4604 was offered for sale and was purchased by David Hands, a man who shared Lobb’s enthusiastic approach to the car. The Bugatti was shipped to the UK where after a period of “looking at it,” Hands made the decision to have the car prepared and sympathetically restored.

Photo: Powerhouse Museum

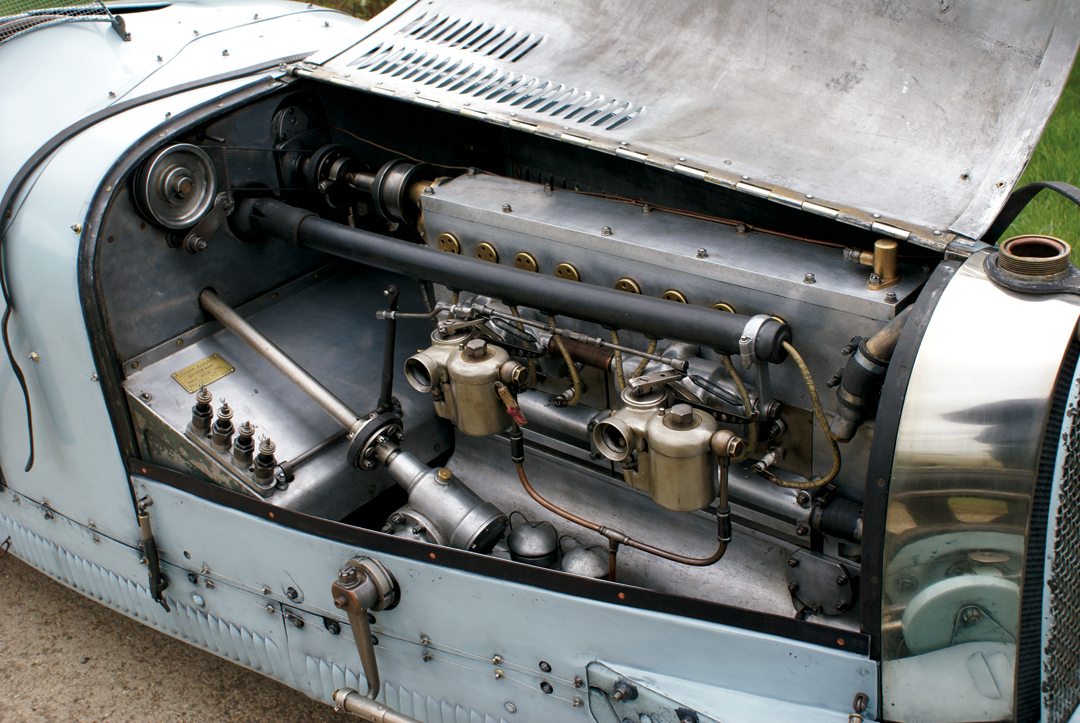

Engine work was carried out by Crothswaite and Gardiner, and although some suggested the car should become a 2-liter to enable it to be reliable during future years, Hands was determined to keep the car as a 1500-cc and preserved as it raced in the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. This was achieved, with many original components used in the rebuild including the crankshaft, connecting rods, carburetors and camshaft.

The body was also repaired and not replaced, and after many hours the shade of blue in which it was to be repainted was chosen. It can be seen in many Bugatti books and photographic albums that the shades of “blue” on Ettore’s cars certainly changed from time to time and were also never of the highest gloss finish. It has been suggested numerous times that the packet of Gitanes in Barbara Bugatti’s apron pocket was the influence for the final color choice. You can also see in photographs that certain cars of the period, and of the same type, are not identical either. Each craftsman responsible for the manufacture of a car was allowed the scope to show off his own flair and skill in the build process of a Bugatti car, thus making each one unique.

Once the body was completed, the car was mated with its chassis and tested prior to its debut at the Goodwood Festival of Speed. The car was enjoyed by many and then, later in its return season, it raced at the Goodwood Revival in the Brooklands Trophy race. Following its UK appearances, 4604 once again made a trip “down under” to take in action at Phillip Island and also parade at an Australian Grand Prix before once more returning to the UK.

Photo: Powerhouse Museum

TIME TO TAKE IN THE VIEW

It is not every day you are handed the opportunity to climb aboard a Bugatti, especially one of such originality, and so I must say I was very excited, if not slightly nervous, to be given this chance. The Bugatti name conjures up something magical, something from that halcyon period—and I am frustrated that today people tend to just think of Bugatti as the manufacturer of the Veyron supercar.

I remember reading books during my formative years depicting the “golden era” of our sport. Hugh Conway—the man responsible for the documentation of the marque—was one such author of books I devoured. His prowess of the written word made him the authoritative voice on these famous cars, and if it had not been for his great work, many Bugatti tales would have been forgotten and/or lost forever. Conway’s Bugatti tomes are legendary and I will admit I had a quick swot before heading toward 4604. First impressions in life are everything, and my first impression on standing alongside 4604 was that the car was a thing of beauty. Small and purposeful, the Bugatti Type 39 can be described as a “real” racing car. Built to look fast, and built to go fast.

Its slender, well-crafted body does indeed look fast, and as I fastened my helmet and snapped my goggles into place I couldn’t help but reflect on the car’s career at Montlhéry and Monza and what Meo Constantini—former flying ace, two-time Targa Florio winner and sometime Bugatti race team manager—would have been feeling as he climbed over the car’s side for the very first time. I took that same step and climbed in to maneuver my legs under the large walnut-rimmed steering wheel to sit on the leather seat. I found I had to add some additional padding below the base cushion to obtain my required seating position, but once that had been accomplished I settled to take in the view from the right-hand side driving position of 4604.

The seating position was good, with the wheel close to my chest. This might feel awkward in some cars, but in the Bugatti it felt perfectly natural and for me, well-positioned. The gear lever, mounted externally, along with the hand brake, was also just in the right place and the aluminum tonneau, stretching halfway across the passenger side, gave the feel that this was in fact a sporty single-seater rather than a two-seater sportscar. The mesh windscreen, mounted on springs, might not have kept small insects out of my gritted teeth, but it was certainly aerodynamic!

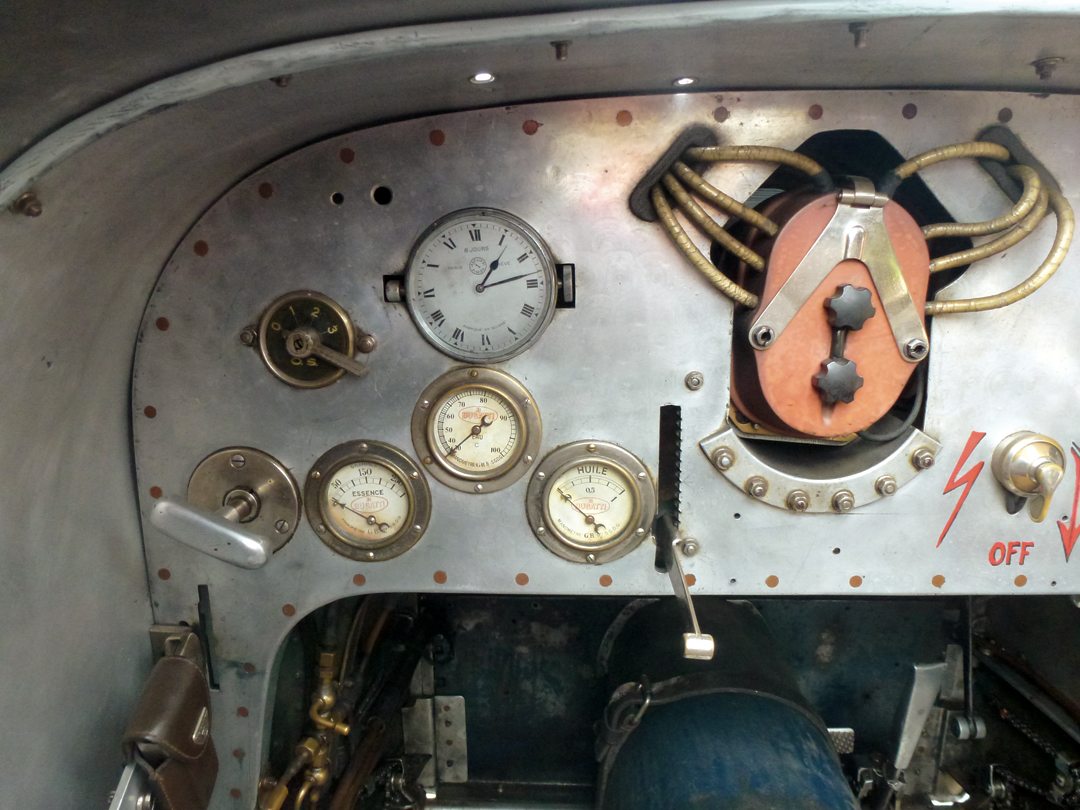

Mounted in the middle of the beautifully crafted dashboard was the magneto, looking not unlike a large spider climbing through the metalwork with its eight plug leads heading toward the car’s straight-8 engine. The dials, including the tachometer, which lets the little 1500-cc indicate happily up to 7,000rpm, and the oil and water pressure gauges were perfectly placed for viewing when seated behind the wheel. Owners of large feet would, however, find 4604 wanting in the footwell department. Small feet, or the wearing of racing boots or narrow shoes, is a mandatory requirement to enable access between the accelerator, brake and clutch pedals.

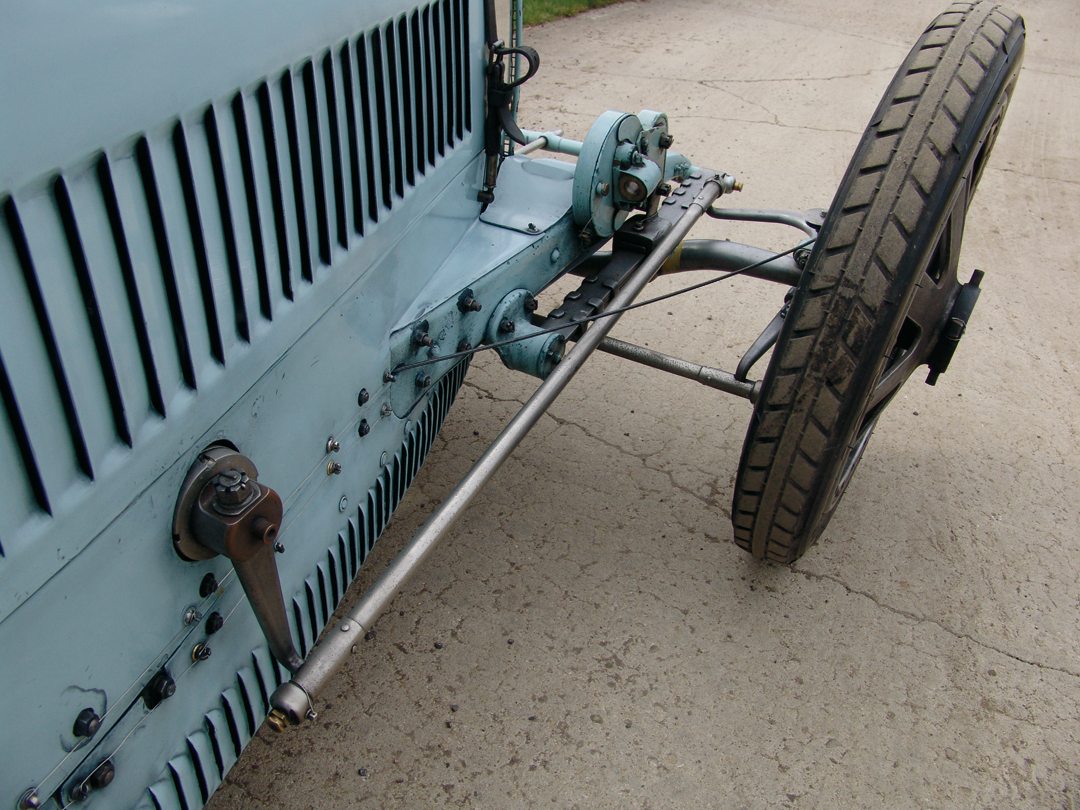

In true Bugatti tradition the spare wheel is mounted on the side of the car and under the bonnet the original Ettore Bugatti chassis plate shows this as car 4604. The beautiful shape of the Bugatti radiator and grill is topped off by a temperature gauge—a rather shapely hood ornament.

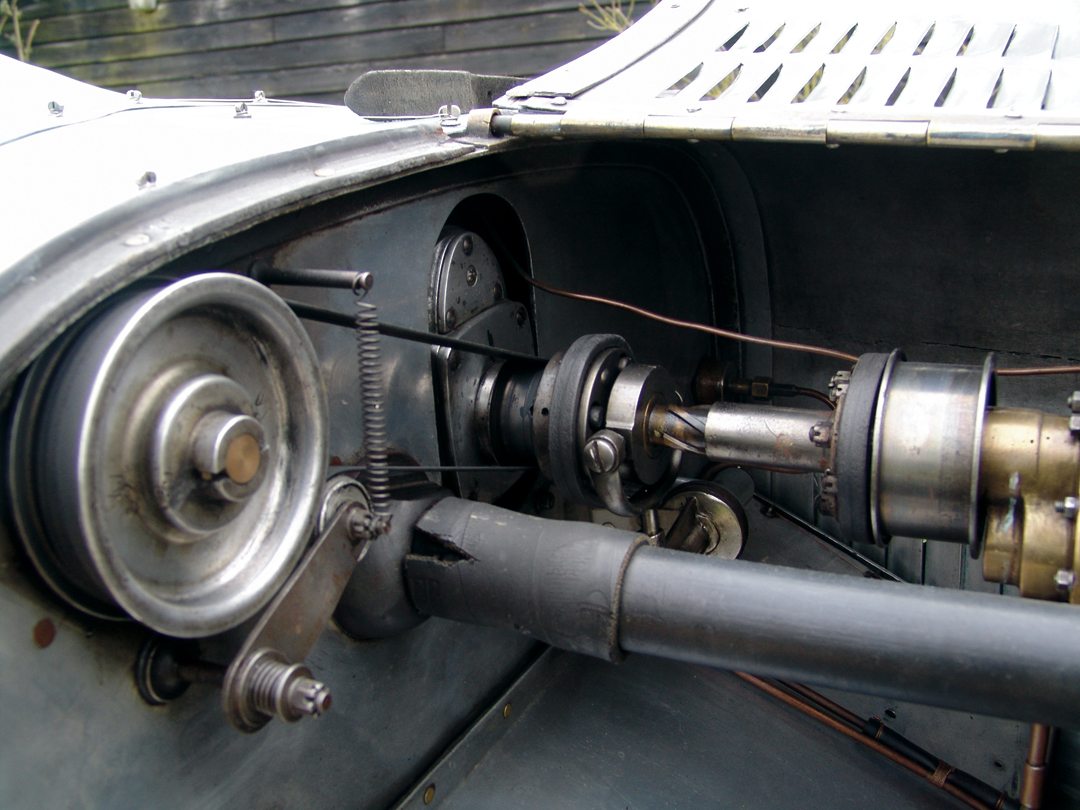

The braking system inside the car was a thing of curiosity to me, as well as beauty. The brake pedal was connected to chain-linked compensators mounted deep in the heart of the car that then couple to cables. It was great to see how this system worked, and it was all very much on show in the cockpit. With the chains placed alongside the feet of the driver and passenger, I noted that long and flapping shoelaces when driving, or being driven in, 4604, was not a good idea!

The car is started by the crank of the handle after pumping up the fuel pressure and flicking the ignition switch to on. The Bugatti has a great little engine sound, readily barking with a crisp-sounding engine note. With no supercharger this Type 39’s short-stroke engine gives its driver strong performance from a gutsy engine that uses its closely matched gears well. The car benefits from precise steering that allows the driver to feel its true characteristics, and on a smooth road surface 4604 is very much at home. To obtain the best from this car you do not have to be a “have a go” hero, the car is responsive, and to use a 21st century racing phrase, gives “good feedback.”

This car is one of the world’s best and most significant Bugatti racing cars. Its originality sets it apart from other examples of its type. I marvel as I recall that this very car was raced twice during the heyday of the Bugatti marque by Meo Constantini. The Italian from Vittorio Veneto took it to victory at Montlhéry and 3rd place at Monza.

Constantini was, at that time, one of the finest drivers in the world, and his driving of the car adds to its unique charm. I have no doubt that its export to Australia for the 1926 season saved it from the modifications that befell its sister cars—including the car that Malcolm Campbell finished 2nd with in the 1926 British Grand Prix at Brooklands, all of which had blowers fitted and other alterations carried out.

Living down under this little car turned out to be very much a survivor, a car from a period that is now just shy of 90 years ago. The mid-1920s were a time when the sport of motor racing was enjoying a popularity boom. This car played its part then, as it does today—a natural born thriller.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis/Body: Steel chassis with aluminum two-seater body

Length: 12-ft 1-3/4-inches

Wheelbase: 7-ft 10-1/2-inches

Track: 3-ft 11-¼-inches

Engine: 1493-cc, straight-8 with short-stroke crank, single overhead camshaft. Three valves per cylinder, twin Zenith carburetors and a dash-mounted magneto.

Power: 90 bhp @ 5000 rpm

Transmission: Four-speed manual with an external gear lever and a wet, multi-plate clutch

Suspension: (F) semi-elliptic leaf springs with forged beam axle. (R) Live axle with reversed quarter-elliptic leaf springs

Brakes: Drums with cable operation

Wheels/Tires: Cast aluminum with integral drums. 5×19 tires

Photo: Powerhouse Museum

Photo: Powerhouse Museum

Acknowledgements / Resources

The author would like to thank David Hands for allowing us to profile this truly superb car. Also to Tim Dutton and the staff at Ivan Dutton Limited for their time and patience during our visit to their workshop on a very cold day! Again, I would like to thank, John Pearson for his kindness and enthusiasm for my endeavors.

The Bugatti Video Reference and Data Book by H.G. Conway, Wychwood UK 1989

Bugatti ‘Le pur-sang des automobiles’ by H.G. Conway, Haynes Publishing, Third Edition 1979