The Mirage story is, in some ways, a rather complex one, in that the Mirage was a rare example of a well-known racing car that had not been developed consistently year by year, as had been the case with Ferrari, Matra and Alfa Romeo in the late 1960s and early to mid-1970s. The Mirage was born from Ford and necessity, and it took some time to establish itself as a marque in its own right. Like Ferrari, Matra and Alfa Romeo, it managed to do that, and became a front runner in the World Sports Car Championship, with notable victories and exciting performances from exceptional drivers.

Photo: Pete Austin

The Mirage was largely the product of the work of two men who had a lasting impact on motor racing. One was rather better known than the other, but the second had a much longer connection with the racing Mirages than the former. We are very fortunate that both wrote comprehensively about their racing careers, so much of the Mirage history is accessible

John Wyer had been the competition manager for Aston Martin Lagonda Ltd. and then general manager of the company. In 1958, a young John Horsman had a job interview with Wyer and was offered an apprentice position with the company. Horsman then worked very closely with Wyer in the later years of the Aston Martin racing program, which was wound up at the end of 1963. Wyer famously joined Ford to sort out the GT40 for international sports car racing, while Horsman went back to education. He was subsequently invited to join Wyer as his assistant, which he did when he finished his course at London’s LSE in June 1964. They were to work closely together for many years to come, and remain friends even longer. Wyer eventually following Horsman out to Arizona to live.

Photo: Pete Austin

Wyer and Horsman were based at the Yeovil Road headquarters of Lola Cars in Slough. In 1963 Lola’s Eric Broadley had been assigned by Ford the task of turning the Lola GT that had run at Le Mans into the GT40. Many Lola and former Aston Martin staff were engaged in this project. The GT40 was unsuccessful at Le Mans in 1964, and failed again at Reims just days later. Ford Advanced Vehicles had been established just before Reims, and when the Reims disaster took place, Broadley left Ford politics behind, taking his staff and some of the ex-Aston people with him. English engineer Len Bailey had been working for Ford in the USA and came to Slough as part of the GT40 project, remaining there after the split with Broadley. Horsman became the engineer responsible for development, preparation and racing at Slough, and the JW/FAV force really began to take off.

The next two years witnessed a serious advance in sports car racing, and the continuation of Ford politics in motor sport. Though FAV had the contract to build 100 GT40s, later reduced to 50, Carroll Shelby had become a Ford partner and assumed much responsibility for Fords going racing. FAV became rather second class citizens, entering few races but doing virtually all the development work. In addition, American Ford engineer Roy Lunn had gotten Ford to focus on a new car, the X-car, a NASCAR-engined chassis based on the GT40, which became the Ford MKII. This took place while FAV was still developing the GT40. When Ford lost at Le Mans in 1965, the FAV program was cancelled, and then reinstated two weeks later. In 1966 FAV was relegated to providing support for customer road and racecars. However, though Ford won Le Mans in 1966, FAV-supported cars won the World Sports Car Championship. Ford had announced that the GT40 build program would end in the autumn, and the very last car was delivered just before Christmas 1966.

Photo: Lou Galanos

John Wyer had purchased the assets of FAV and an agreement to continue to build and sell Ford GT40s. On January 1, 1967, the FAV sign was replaced by one which read J.W. Automotive Engineering Ltd., and the directors of the new company were Wyer, Horsman and John Willment who provided financial investment.

Significantly, Gulf Oil Corporation executive Grady Davis had spoken to John Wyer in March and ordered a GT40 for himself, which was delivered in April, and he was very impressed with the car. The link with Davis and Gulf would mark a turning point for Wyer, Horsman and many others. When Wyer was winding up the arrangements with Ford toward the end of 1966, he visited Gulf Oil headquarters. Gulf Oil Racing was created, and Wyer’s operation had generous finance for the future. Though it did not yet have a name, the Mirage program was underway.

Mirage is born

In 1966 and 1967 there were two championships within endurance racing: one for Group 6 prototypes over and under 2-liters, and one for cars which had been homologated in a production run of no less than fifty cars—Group 4 cars.

As the 1967 season opened, not everyone realized that this would be the last year for the unlimited prototypes. The FIA had completely reversed its earlier tendency to favor GT cars, and now were promoting the prototypes. If the teams had known what was coming, 1967 would have been a less interesting year. The JW team that would now be racing under the banner of the Gulf Oil Racing Team, knew the rule changes were coming, but considered it was still a good move to build an “unlimited” prototype. Regulations such as windscreen dimensions had already changed and Len Bailey had drawn up plans for what was essentially a GT40 that incorporated the new rules. This meant JW had a design for a car with a lower frontal area and less drag.

Photo: Lou Galanos

In the early months of the year, the team built what they viewed as a better version of the GT40. This had all the advantages of Len Bailey’s aerodynamic work. The new car used a Ford engine, though not the 289 cubic inch unit. Among the pile of spares that JW had received from Ford after Le Mans in 1966 was a large supply of new four-bolt blocks and related components. JW assembled the blocks with a different crankshaft and the new unit was 305 cubic inches or 4999 cc. The car used the ZF gearbox, BRM mag alloy wheels and Girling disc brakes with 11.95-inch ventilated discs, with larger calipers. John Horsman, in his book Racing in the Rain, describes the new car:

“…a standard GT40, but the body panels were made of a very light fiberglass reinforced by strands of carbon fiber, supplied to us initially at no charge by the aircraft industry looking for alternate uses of this new material. I believe we narrowly beat McLaren as the first racing team to use carbon fiber.”

It is not entirely clear when the name Mirage was chosen for the new car. It seems that it probably wasn’t too long before the first tests at Snetterton on March 21. John Wyer had asked John Horsman to put together a list of possible names, which included Falcon and Peregrine. Wyer composed his own list and when they discovered that Mirage was on both lists, the decision was made. With the Gulf backing, the Gulf colors would be used, though they opted for the lighter blue and orange combination used by Gulf in California rather than the official darker blue. These colors would become very famous indeed over the next several years, and if there are any “iconic” colors in racing, then they are the Gulf blue and orange.

The new Mirage was designated as an M1 with chassis number M1/10001. Wyer says in his book that the Mirage was first designated as M1/500 in the light of its using the five-liter engine, though that name didn’t stick. The M1 did nine races that year and managed five victories at Spa, Karlskoga and Skarpnack in Sweden, Montlhéry and Kyalami with drivers including Jacky Ickx, Dick Thompson, Jo Bonnier, Paul Hawkins and Brian Redman.

JW focussed mainly on running GT40s in 1968 and then appeared with the M2 for 1969, a good looking closed coupe with a 3-liter BRM V12 engine. This was unreliable and its best result was a 7th for Hobbs and Hailwood at Spa. In July that year, the new M3 made its debut at Watkins Glen, though it wasn’t entirely new. The Ickx/Oliver car at The Glen was one of the M2s with the roof removed, but with a 3-liter Cosworth DFV fitted. Though it showed some promise, it only won at Imola in the hands of Ickx before being superseded by a new design some two years later.

As all racing fans know, and as the team knew in 1969, Porsche invited Wyer to run the new 917 for 1970 and 1971, and these were tremendously successful years. Wyer was very proud of the performance the JW Gulf team had managed, and was very disappointed at the end of 1971 when there was no acknowledgement of this at all. Then Porsche announced that Roger Penske would be running the Can-Am effort in 1972, with no word to Gulf or JW about this beforehand. Wyer decided he no longer wanted a front-line role, and turned down an earlier offer to go work with Gulf. Wyer then agreed to act as a consultant, and as he and Grady Davis had great faith in John Horsman, they set up a small subsidiary company called Gulf Research Racing at Slough, with Davis as president and Horsman as managing director. Wyer would be a non-executive director, and would be brought back for a short spell in 1975 as president when Davis retired. Wyer later made it clear that he fully believed the return to three liters was disastrous for sports car racing, and made it very much a poor relative to Grand Prix racing.

Photo: R. Forster

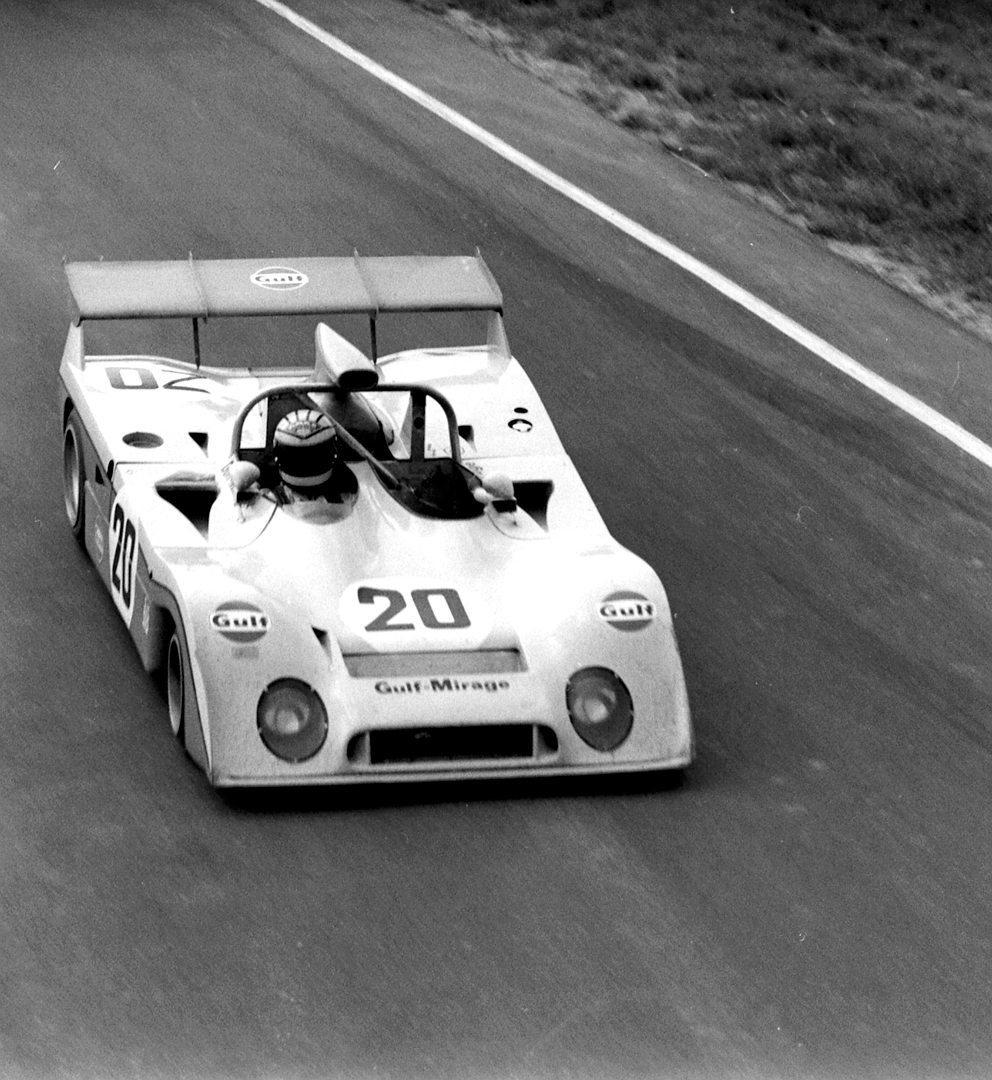

The name of the new company was released in January and Autosport announced that the team would run a Group 5 Mirage with a DFV engine designed by Len Bailey, and would debut at Sebring in March with possibly Derek Bell and Gijs van Lennep as drivers.

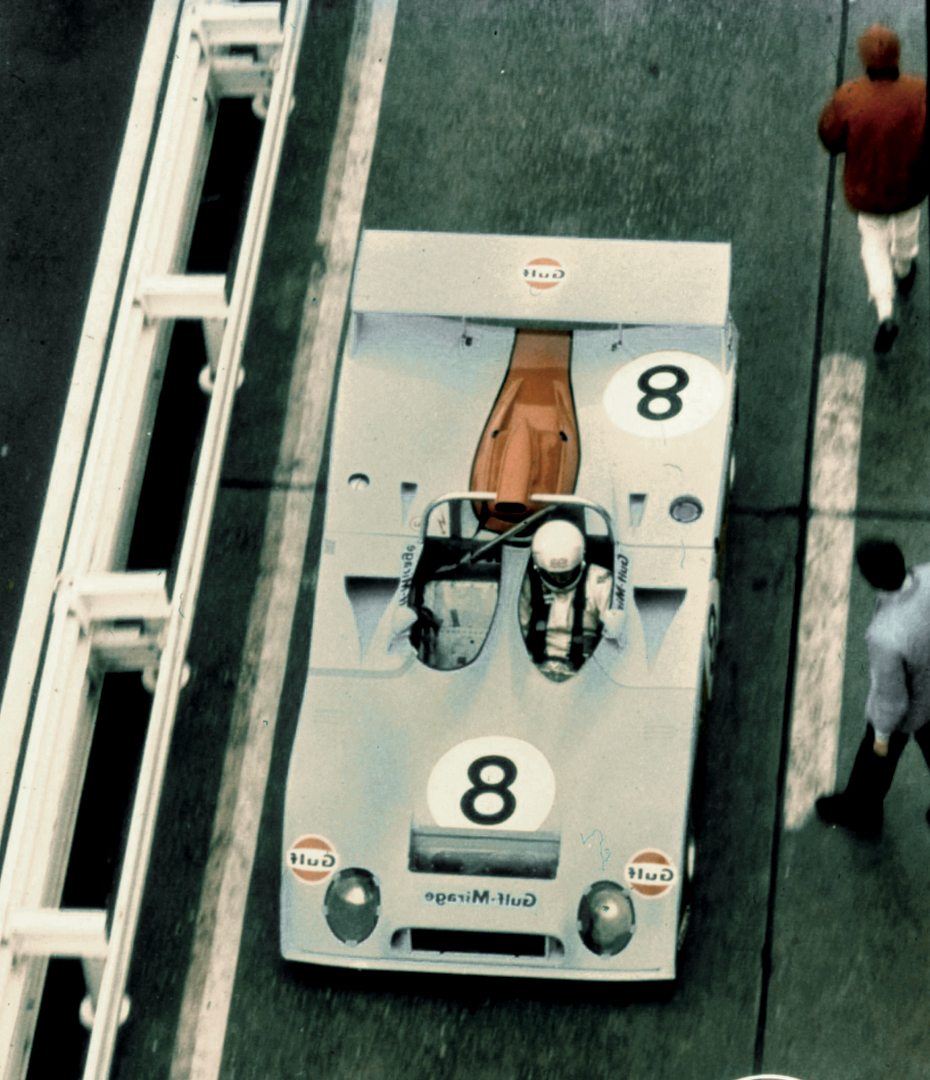

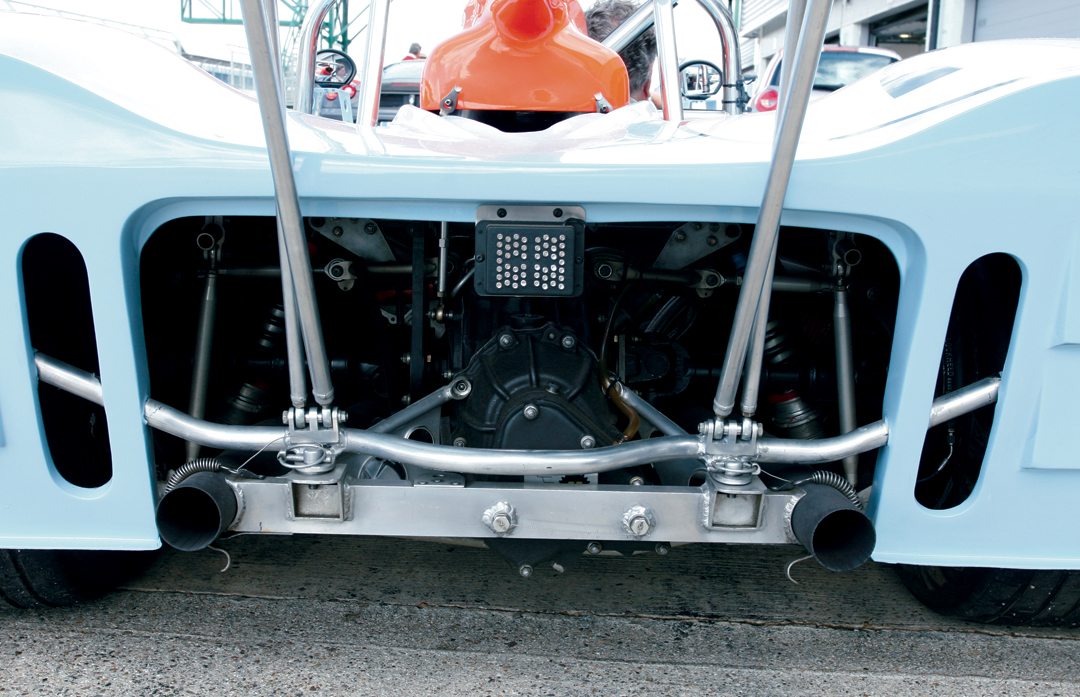

The car first appeared at Silverstone on March 14 with Bell behind the wheel. Bailey and Wyer were present to watch the Gulf-Mirage M6, whose debut had already been delayed by non-delivery of parts blamed on the coal miners’ strike. The monocoque tub was reinforced by mild steel substructures, skinned in 18-gauge L72 aluminium alloy except for some of the semi-stressed panels. Side pontoons carried two 60-liter fuel tanks and pumps. The car was designed so that it could use either the DFV or a Weslake V12. Thus with the V8 installed, there is room in the engine compartment for cooling, and a degree of flexibility as to where mountings and brackets can be fitted. There are fabricated steel rear suspension crossmembers. The lower rear suspension mounts are via a magnesium casting bolted under the gearbox, with front suspension by lower wishbones, fabricated top links, trailing arms and outboard coil/spring damper units. There are hub-mounted front and rear Girling ventilated disc brakes. The car, on Goodyear tires, ran for 25 laps before the drive to the mechanical fuel pump, which also drives the oil pump, failed, but it did more laps a few days later at Goodwood—a total of 169 miles before being shipped off to Sebring. The car had been late arriving at Slough so there were real worries about the limited testing, but the new car looked the business. The lone chassis sent to Sebring was M6/601

M6/601…a long and winding road

Fortunately, a number of Mirage cars survived the ravages of professional sports car racing. With the popularity of historic racing, and with a number of championships for these machines such as the Classic Endurance Championship, several cars have been restored and are seen in Europe and the USA.

The car you see here is the first of the John Wyer/John Horsman Mirage M6 cars that was later up-graded to GR7 format and was chassis M6/601, and then GR7/701. It has a stunning history and still races in historic sports car events in the hands of its Belgian owner, Marc Devis, who kindly allowed the author to test the car at Silverstone. It turned out to be a particularly significant occasion as Vern Schuppan came along to share in the driving reunion.

Photo: Lou Galanos

M601 was tested extensively by Derek Bell prior to the start of the 1972 season. It ran as a team car through 1972-’73-’74, scoring the most points of all the team cars, covering a distance of 15,567 miles driven by Bell, Schuppan, Jacky Ickx, David Hobbs, Carlos Reutemann, Gijs van Lennep, James Hunt, Howden Ganley, John Watson and Tony Adamowicz. The history is pretty impressive.

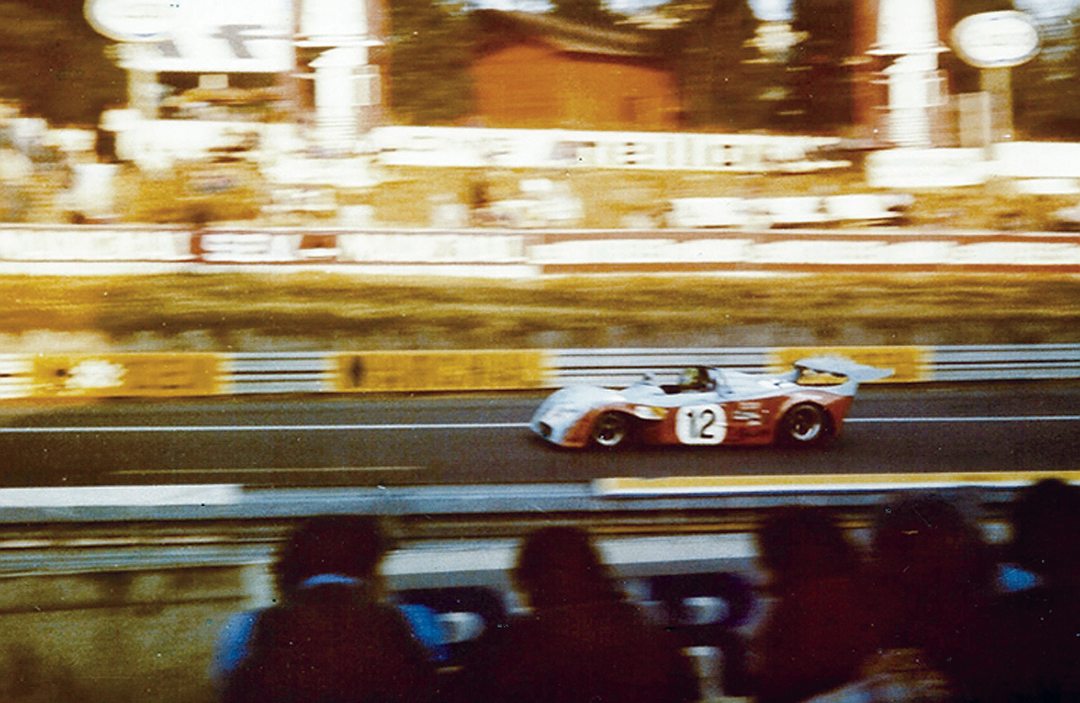

The early races, again, showed promise though it didn’t finish at Sebring in 1972 and was not classified at Brands Hatch. However it managed 4th at the Ring, before being joined by M6/602 in Austria. Tony Adamowicz was in the team with van Lennep at The Glen, though 601 was not running at the finish, while Bell and Pace were 3rd in 602. In 1973, it didn’t finish at Daytona and Monza, and then came the great Spa 1-2 for the new 605 and 602. I was at that race at Spa driving a Dulon 2-liter with Tony Goodwin and we shared a garage out in the country with the JW team. I had bought a Mirage M5 Formula Ford from John Wyer and had raced it in 1972. We were on good terms, and it was a privilege to be there when Derek Bell and Mike Hailwood, and Vern Schuppan and Howden Ganley got that great result for the hard-working team. Derek Bell then won his heat and the final at Imola in the car, and James Hunt joined Bell to come 2nd at Kyalami.

Photo: Hubert

1974

In theory the story could have ended here as the Mirage name was retired and Gulf requested that the cars now be called the Gulf GR7, rather than develop the Mirage M601 into the Mirage M701. Apparently Gulf’s feeling was that “Gulf Mirage” was always shortened to “Mirage” and they lost the publicity opportunity. Interesting, all these years later, everyone I know refers to the “Gulf Mirage!” For the most part, they were the same cars, though a very substantial use of titanium in many components saw the weight tumble to 1588 pounds, the lightest it had ever been, though still not down to the minimum weight. Some components had to be strengthened to deal with the Cosworth vibrations, unlike the V12 Matra, so the French team still had an advantage.

Bell and Hailwood had been confirmed as drivers in December, and news reports said the team was interested in retaining James Hunt, though John Horsman later said he was disappointed that Hunt was not quicker, nor did he have the commitment that Bell and Hailwood did. Horsman reckons that Jackie Oliver was the only F1 driver who became a sports car driver.

A major test session was organized for the last week in February at the Paul Ricard circuit. Though the plans for 1974 at first indicated that the team would only be running one car except for Le Mans, three cars were brought for the test session. These were GR7/702, 703 and 704, which were M6/602,603 and 604 from 1973. M6/605 had a cracked rear steel bulkhead and was made into a show car with the older, heavy bodywork, and was not raced again by the team.

GR7/701 first raced at Le Mans in 1974, driven by Schuppan and Reine Wisell, but it failed to finish. Bell and Hailwood were 4th in 704. It was then used as the T-car at Zeltweg, and in August Bell and Ickx took a strong 3rd at Paul Ricard. Bell and Hobbs managed another 3rd at Kyalami at the end of the year in what turned out to be 601/701’s final race for the team. Some of M7s, though not 701, were sold to German privateer George Loos for 1975, while Wyer convinced Gulf to stay one more year and built the GR8—which won for Gulf at Le Mans, finally.

701 was retained for some time by the team, and eventually was restored in the USA in 2003 when it was in the ownership of Jeff Lewis, who used the car only occasionally after the completion of the restoration. It was bought by Marc Devis in 2006 and was prepared by Pearson Engineering in the UK, and it was brought to Silverstone for our test by Gary Pearson.

Driving M6/601-GR7/701

It is always very special to drive a well-known racing car, and is even more special when it is not only something you saw in period but raced against as well. And finally, there was the chance to run the car with one of its successful drivers from the 1970s, in this case, Vern Schuppan. Vern and I had maintained contact from the “old” days—we had done the very first Avon Tour of Britain in 1973 together for Ford.

It was a special day at Silverstone as the about to be announced Rofgo Gulf Collection was present with six cars that had gained fame in the blue and orange colors of Gulf, including the Porsche 917, so the Mirage was a star attraction. Of course it fired on the button, the Cosworth-DFV bursting into life and causing lots of fingers to be pushed into ears! With a caution not to ride the clutch and go easy on the intermediate tires, it was off to do some laps of the Silverstone Grand Prix circuit.

There is little to compare, in sports car terms, with driving something that excelled on fast circuits in period and is still very much at home in a high-speed venue. Though there was just a hint of a miss at low speeds, the DFV warmed to the task, the Hewland 5-speed box very much up to the job as always. The Mirage had numerous aerodynamic improvements over the years it raced, and grip and road-holding is as good now as it was in 1973, when it impressed all the other major teams. Even Ferrari made enquiries about a Mirage chassis with a Ferrari engine in it! Wanting to preserve the rubber, there was no hard acceleration out of the mixture of Silverstone corners, all the speed necessary coming in a straight line. A special feeling comes with looking down the long Hangar Straight, then finding yourself at the end of it, and working out just how much you want to ease up before turning into Stowe. The hairs go up on the back of your neck.

M6/601/701 is still an incredible machine. As Fittipaldi always said “my car has nice balance.” Pre-modernization Silverstone was a tester. Only a good car with well tried brakes could go deeply into Stowe at the end of the straight, a key to using fourth gear on the limit down through the Vale. Down to third—and possibly second in traffic—for the exit of old Club and then quickly up through the gears for the Abbey chicane, and then again on the limit up the gears through Bridge. There is a non-stop mile of testing slow and medium corners from Stowe to the Complex, up and down the box, the DFV working at 8500 rpm and the Gulf colors flying.

Vern did his laps, and like the old days, we retired to discuss laps, corners, revs, and those superb moments when Gulf, Wyer, Horsman and Mirage were at the front.

SPECIFICATIONS

M6/GR7

Presented: March 14, 1972

Type: Two-seater open car

Engine: Ford Cosworth DFV V8

Power: 445 bhp @ 10,500 rpm

Capacity: 2993-cc

Brakes: 4 ventilated cross-drilled discs

Transmission: M6-Hewland DG300; GR7-ZF5DS25/1

Chassis: Aluminum monocoque with steel reinforcements, fiberglass reinforced polyester body

Wheels and Tires: Firestone tires, various sizes over three years

Acknowledgements / Resources

Thanks to Marc Devis for the privilege, to Gary Pearson for the help, and to Vern for the memories.

Horsman, J., Racing in the Rain. David Bull Publishing Arizona 2006

Wyer, J., The Certain Sound. Automobile Year Switzerland 1981 Ed McDonough’s new book, Gulf-Mirage 1967 to 1982, was published in 2012 by Veloce www.veloce.co.uk at $29.95