“Just turn the key and it will start,” I was told, as the door of the Tojeiro-Buick registration number TSU 719 was closed. A quick turn of the key to the right and a large pump of the throttle and it did! Instantly aware of the growl from the car’s Buick 3.5-liter V8 engine, mounted just inches behind my head, the noise was somewhat comforting as I became used to my home for the next thirty minutes.

Engaging first gear and releasing the clutch, the car rolled forward, and with the sun streaming through the front windscreen I was off. My first feature article for Vintage Racecar was underway. I was at the wheel of an Ecurie Ecosse team car, driving the machine once raced by my hero, three-time F1 World Champion, Sir Jackie Stewart OBE!

Background

The part played by the little Tojeiro-Buick in the history of David Murray’s famous Ecurie Ecosse team was in a period when many will rightfully say the team’s glory days were over. Ecurie Ecosse’s well documented story started back in the early 1950s, and I feel a quick recap of those days will help set the scene here. Murray, himself a keen amateur driver, had a dream of creating a Scottish Formula One team, and to help him reach that goal he formed his squad centered around owner drivers who all had access to the supercar of the day, the Jaguar XK120.

The stunning Jaguar was to provide much success for the team and its drivers, countless victories being scored, and, as time progressed, the weapon of choice in the Ecurie Ecosse stable became the Jaguar XK120C—the C-Type. In those early days, Ian Stewart won eight times from nine starts in his C-Type and after the success of Jaguar at Le Mans in 1953 with the C-Type, the purchase of the “lightweight” works C-Types took place. Naturally, the D-Type followed, and one of Coventry’s finest was added to the Ecosse stable, and it was on June 28-29, 1956 at the Circuit de la Sarthe the Ecurie Ecosse story became legend when victory at Le Mans was secured.

For many, the win came as a surprise, but to Murray his own expectations for the race had always been high. Prior to the team’s departure to France he had been asked where he thought his car might finish. “I will only be happy with a top-five result,” was his answer.

When the factory-entered Jaguars failed, the Metallic Blue

D-Type of Ron Flockhart and Ninian Sanderson was in a position to take the lead, and the win. Ecurie Ecosse—a direct translation in French to Team Scotland—was well and truly on the map.

One year later and Ecurie Ecosse repeated their Le Mans success—finishing not just 1st but 2nd as well. The lead car was driven, again, by Ron Flockhart, this time partnered by Ivor Bueb. Ninian Sanderson and John Lawrence took 2nd. A 1-2 finish at Le Mans was a remarkable performance for the small team from the backstreets of Edinburgh—Merchiston Mews to be precise—and their blue and white cars were now some of the most famous racing machines in the world.

Throughout the remaining years of the decade Ecurie Ecosse could be seen on-track with a variety of machines ranging from Lister-Jaguars to the Tojeiro-Jaguar, famously crashed by Masten Gregory at Goodwood in 1959. As the ’60s appeared, the famous colors appeared on a Cooper-Monaco and an Austin-Healey Sprite before the Tojeiro came on the scene.

Photo: Pete Austin

The Tojeiro became the last Ecurie Ecosse car to grace the track at Le Mans while Murray’s team was in action. The doors finally closed as the ’60s came to an end, and the name Ecurie Ecosse disappeared into the history books. However, the halcyon days were fondly remembered and, in 1983, Scottish businessman and racer Hugh McCaig made moves to return the team to the track. Under his stewardship, Ecurie Ecosse experienced a revival, and gained notable success in the Group C2 category for a number of years.

Further forays into the British Touring Car Championship followed for McCaig’s team, and the story returned to the track once more in 2012 with the team active in modern GT racing with a BMW Z4. The Ecurie Ecosse dream of adding further Le Mans victories to David Murray’s tally lives on.

The Tojeiro

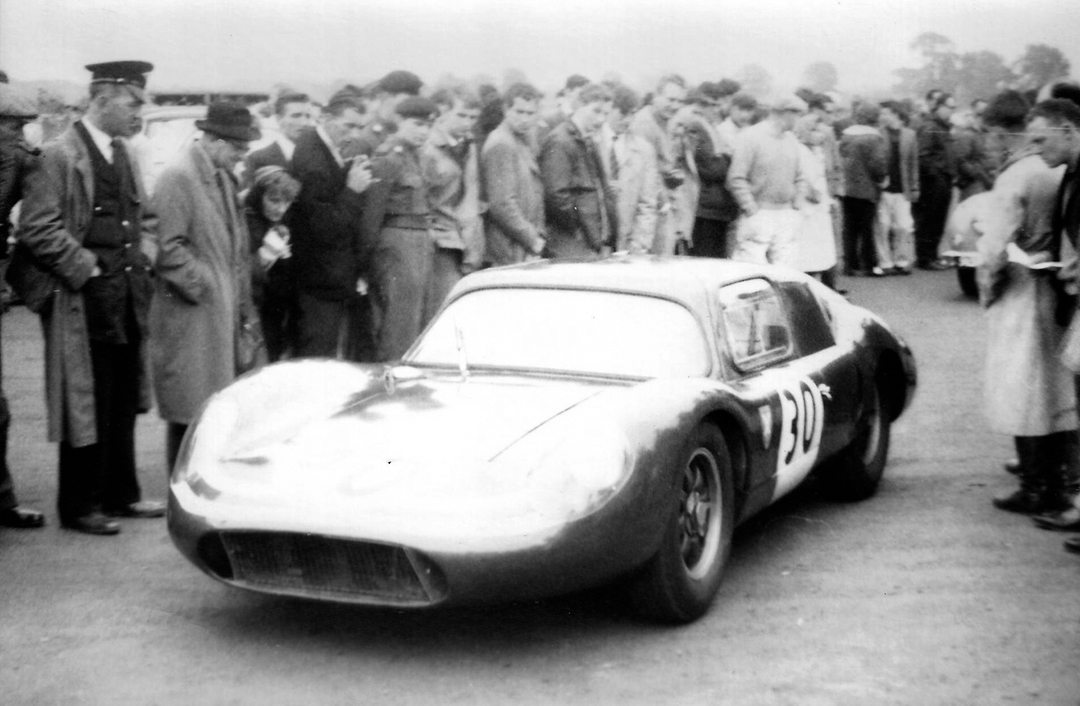

Le Mans success in 1956 and 1957 left David Murray and his loyal band of followers wanting more. The numerous attempts on the Grand Prix d’Endurance for the team that followed, ended mainly in retirement. As 1962 approached, Murray was intent on having another crack at the race, and commissioned two GT-style coupé cars from the well-known constructor, John Tojeiro. This new car would be a mid-engined coupe, powered by a Climax engine.

Murray’s choice to have the Tojeiro built was groundbreaking. The car was, quite simply, ahead of its time. By the time work commenced on the cars, 1962 was already a couple of months old and so the most important race on the Ecurie Ecosse agenda was not Le Mans, but the race to be ready for Le Mans!

Tojeiro’s original design plan was to evolve the chassis of his Formula Junior using the same basic concepts regarding front and rear pickup points. Stretch the chassis to become a two-seater GT car, position a 2.5-liter Coventry-Climax in the back, the same as the Ecurie Ecosse Cooper-Monaco, drape a coupé body over the top and create the world’s first proper racing coupé.

Photo: Alan Collins Collection

Work progressed, sometimes slowly, as all parties put their thoughts to the project. Stan Sproat, Murray’s technical guru and an integral part of the Ecurie Ecosse story, was despatched to the Tojeiro workshops in Cambridge from Edinburgh to pull the parts together. As time went on, it became evident to Sproat and others that two cars would not be ready for Le Mans, so all efforts were put into Chassis 1 and its completion.

One major problem was how the car’s heart, the 2.5-liter Coventry-Climax engine could be maintained to last a 24-hour race. The engine was not designed for long-distance running, and the engine’s manufacturers seemed short on time and ideas as to how this could be attained. With engine concerns just one of the numerous problems encountered, the development of the car’s body shell was also slow work. Thanks to the work of Cavendish Morton, the body shell finally appeared, produced by Wakefields of Byfleet, and was mated to the chassis. The car, unpainted, was taken to Le Mans with no testing under its belt and with spring rates guessed by Tojeiro. It was thus sent out on-track to be driven by Tommy Dickson and Jack Fairman.

Photo: Dick Skipworth Collection

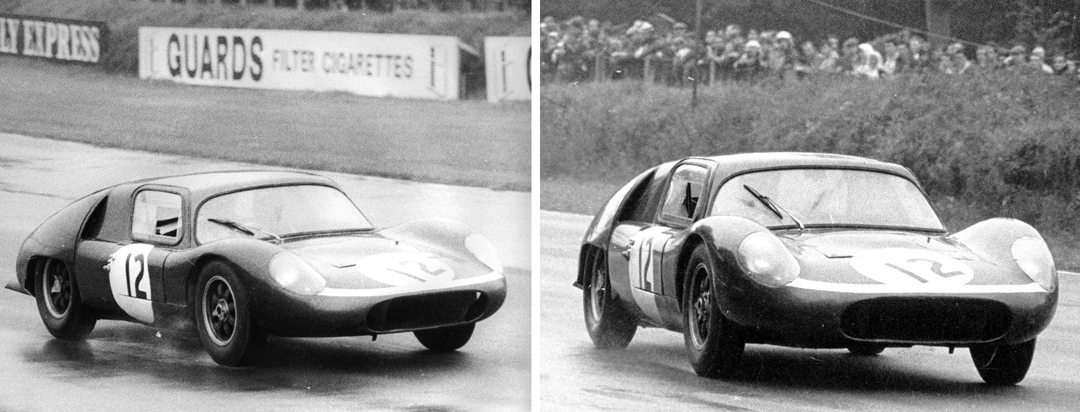

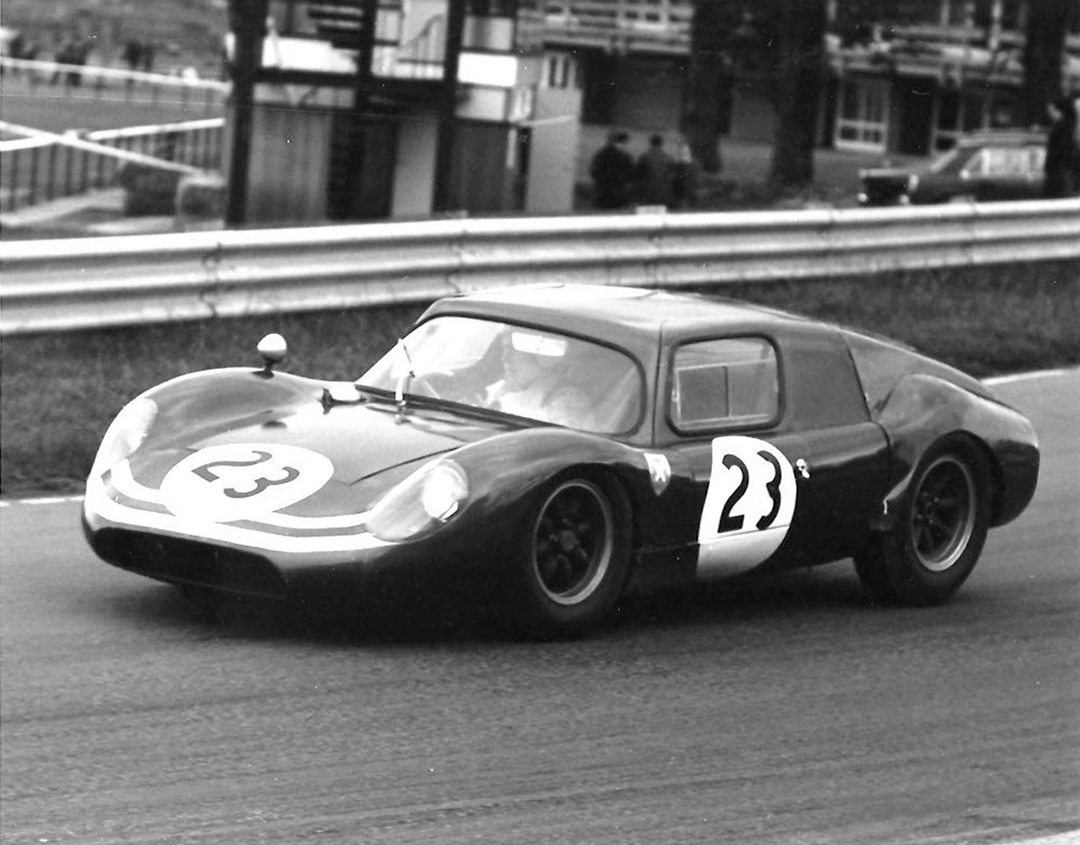

The car made it to the grid for the 1962 24 Hours of Le Mans, and it ran for eight hours. It may not have yielded the results hoped for by Murray and his associates, but for it to even make the race was something of a miracle. The project had been late in starting and the rush to have the car ready had been frantic. Retirement for the number 25 machine came when the gearbox selected two gears at once, bringing the car to a halt “with a large bang.” Le Mans 1962 was over for Ecurie Ecosse, and the Tojeiro would not appear at La Sarthe again. The car suffered damage in a crash at Brands Hatch, with Fairman at the wheel, and on a more successful occasion achieved a lap record during a speed attempt at Monza in the late days of autumn.

On the notoriously rough banking, Fairman pushed the little car hard. A record of 152 mph was equalled, but not broken, and the car was pushed from the track with smoke billowing from its engine compartment—it had been hard work!

For four years Ecurie Ecosse developed and further enhanced the Tojeiro and its design. The team very much returned to its roots with racing in Britain—European trips were no more for Ecurie Ecosse, and there was a feeling that the team was searching for results with minimal expense.

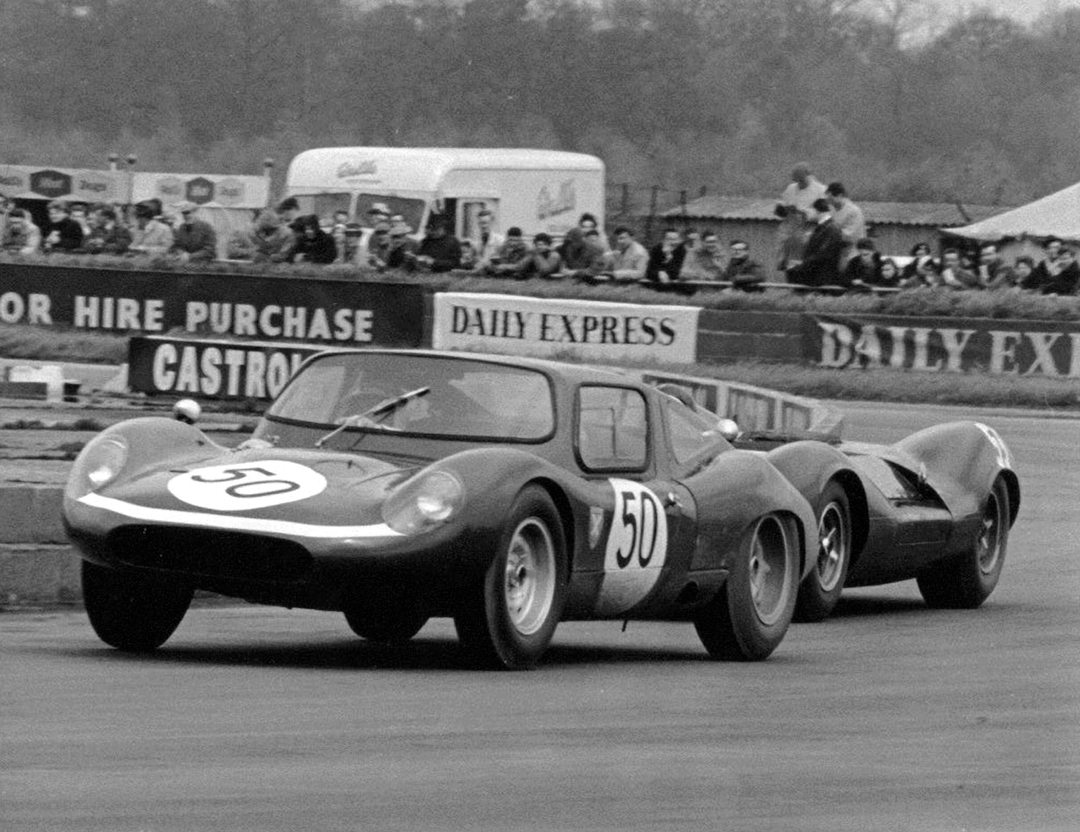

As the Tojeiro project continued, it is also fair to say that the star that was Ecurie Ecosse began to fade. The team was not the force it had been, and Le Mans success was becoming a distant memory. However, for the faithful, the blue and white cars continued to race, and with the Coventry-Climax going back into the Cooper-Monaco, the Tojeiros now very much became V8 machines, with Stan Sproat-engineered Buick engines installed. The engines arrived at The Mews in packing cases straight from America. The engines were dry-sumped and, with U.S.-sourced conrods fitted, they delivered an impressive 228 bhp, yet still short of the output of the Climax they were to replace. The American Buick seemed just right for the job though. It had plenty of torque and the engine delivered its power through a broad rev range. Needless to say, the body shell of the car had to be altered to accommodate the new running gear, and that was carried out before the car made its first appearance. Subtle changes to the car’s shape continued throughout the rest of the Tojeiro’s career to provide better aerodynamic efficiency, or not, and to allow the use of larger wheels and tyres.

Photo: Dick Skipworth Collection

Rising Scottish star, Jackie Stewart, got to play in both the Cooper-Monaco and the freshly re-engined Tojeiro. In the Cooper, Stewart won eight times, before crashing heavily at Oulton Park. The Tojeiro-Buick was not to be such a happy hunting ground for the future World Champion, but he certainly gave it his best shot!

An exceptional talent, wee Jackie got the best out of the Tojeiro-Buick. Victory champagne was Stewart’s in June of 1963, when he drove the car to success at Charterhall one month after it had retired at Silverstone in the hands of Douglas Graham. Throughout 1963 and 1964, Stewart was to be seen in action at the wheel of both Ecurie Ecosse Tojeiro machines. With Buick power, Stewart won at Snetterton in May ’63 and, in the Ford variant, took a 3rd and 6th in ’64. John Coundley was also successful with the Ford version of the car, winning at Brands Hatch; he also bagged a 2nd place as well.

At the end of the 1965 season the Tojeiro-Buick was sold off by Murray and the Ford version, now an open-topped two-seater, crashed at Brands Hatch with Bill Stein at the wheel. The car was destroyed and Stein lucky to escape with his life.

Eric Broadley’s Lola was rolled out at the London Racing Car Show in January 1963, and was designed specifically to take the powerful Shelby-Ford 4.2-liter V8. Broadley’s Lola had a far stiffer chassis than the Tojeiro, and became the benchmark for the future Le Mans-winning Ford GT40. The Lola is regarded as the starting point for cars of the next generation, but in truth, David Murray and Ecurie Ecosse threw down the gauntlet in this arena with their own back street creation, the Tojeiro. It may not have scored the success everyone hoped for, but it did take David Murray to Le Mans for the final time.

Enjoying the Autumn Sunshine

The chance to drive an Ecurie Ecosse team car is rare. A chance to drive a car raced to victory by Jackie Stewart even more so. The Vintage Racecar team here in the UK jumped at the opportunity to give the Tojeiro-Buick a run when offered the opportunity by its current owner, Dick Skipworth.

Photo: Alan Collins Collection

Under a beautiful September sun, the opportunity to stretch the car’s legs was ours, and we all made our way to the famous Kop Hill in the Buckinghamshire town of Princes Risborough to undertake the task. Kop Hill was one of Britain’s leading motorsport venues during the formative years of our sport in the early 20th Century. A closed stretch of public road gave thrill seekers the chance to pitch man and machine against each other along a demanding uphill road course. Sadly, an accident in period saw the event halted, bringing to an end competitive events on public roads here in England. However, a dedicated bunch of enthusiasts, including Dick Skipworth, have returned the event to the very same hill, albeit now as a demonstration, rather than a timed competition.

Skipworth is a proud collector of all things Ecurie Ecosse. His stable includes numerous team cars and the famous Ecurie Ecosse transporter. His collection was center stage at Kop Hill giving those who knew something of the team’s history something amazing to look at and, for those who didn’t, the opportunity to gaze in wonder at the stunning blue cars that sat before them.

In turn, all of the cars made their way “up the hill” to the delight of the watching crowd, and then it was the turn of the Tojeiro-Buick. Granted special permission for the purpose of this feature article, the organizers of the Kop Hill event gave us exclusive access to the hill so that we could push the car just a little harder than the demonstration cars seen earlier in the day.

When you hear the Tojeiro being described as the “Little Tojeiro” that just about sums it up. The car is low, and for someone of my average height it is still some kind of contortionist maneuver to climb aboard. The small doors lift up and out for access to the cockpit, but do not reach a 90-degree angle. Legs go in first and then it is a wriggle down into the cockpit. I would describe it as snug!

While researching this article I read some notes that Jack Fairman had written following his Brands Hatch accident at the end of 1962. He commented that the tight fit of the cockpit had probably stopped him from being injured in the crash, as he simply couldn’t go anywhere! I now know how he felt. With crash helmet on, my head scraped the inside of the roof line, and it was only when I pulled away from the paddock area that I managed, with a little bit of shuffling in the seat, to find a comfortable posture. Once this was achieved, however, the driving position was good, and all the switch gear and right hand-mounted gear lever were within easy reach.

Dick Skipworth’s mechanic, Ray, offered me a pointer, be gentle on the clutch—first gear might be difficult to find. But first was found easily enough as the revs picked up. The Buick’s great torque, as reported by Jackie Stewart in period, was evident as I started my first run up the hill. The gear change was slick, a short throw of the lever as first became second and then third. Checking the gauges to make sure everything was as it should be, I settled down to enjoy the experience and contemplate what it would have felt like to be Jackie racing to victory at Charterhall or Snetterton.

The driving position, save for the narrow width of the cockpit as a result of having a passenger seat alongside, is not dissimilar to that of a single-seater of the period. The pedal set is placed fractionally to the left of the seating position, but if you were to close your eyes it would feel very much as if you were strapped into a Formula Junior or similar.

For a small car, the windscreen aperture is surprisingly wide. The screen wraps around to meet the door openings, and the view of the road from the cockpit is good— although I am not sure if my opinion would be the same at 165 mph in the dark and rain halfway along the Mulsanne Straight!

The bulkhead, that was not present during the early period, makes you feel safe as it retains the Buick behind you. The roar of the throaty V8 engine is a constant, and, as I said earlier, a comfort. It is a satisfying sound, a proper racing sound, and through the twisting turns of the Kop Hill the V8 feels like it would really like to go faster.

Being a hillclimb course you eventually reach the top, and so it is soon time to change direction and start my first descent. With the aid of the track marshals, the car is turned around. Unlike first gear, I found reverse slighter harder to find, but soon set off in a downward direction for my second run.

Going downhill, the car begged to do what it was built for—race. The V8 pushed the car along, and the chassis responded beautifully through the tighter corners—a joy to drive.

The final uphill run was our fastest action of the day. Swift gear changes and very smooth delivery of power to the period-style Dunlop tires allowed me to gain the true Ecurie Ecosse experience. I recall what Jackie Stewart once said, jokingly, that the Tojeiro-Buick was “one of the worst cars he had ever driven.” But, Jackie Stewart drove many “good” cars. In fact, I don’t believe Jackie drove many cars that weren’t “good.” That’s the mark of a great driver. And being a great driver, you must always make sure you are in the right place at the right time to allow yourself to be driving the best car you can.

“I was pleased to follow in the footsteps of my brother, Jimmy, by driving for Ecurie Ecosse,” said Jackie Stewart. “My brother was winning races and I was tremendously proud when he was offered a contract to drive for Ecurie Ecosse. He signed on the dotted line without hesitation and followed in the footsteps of many famous Scottish drivers.

“David Murray phoned me in February 1963 and asked if I would like to drive for Ecurie Ecosse,” Stewart recalls. “They were the famous team with the metallic blue cars that my brother had driven for. They were successful and I agreed. Initially, I was to drive the Tojeiro-Buick, and then maybe get an outing in the Cooper-Monaco.

“It was during this time Helen suggested that my helmet was plain and she added the tartan band to it. In many ways the Jackie Stewart story started here with this car and Ecurie Ecosse.”

Now, the Tojeiro-Buick may not have been the best car Ecurie Ecosse ever owned—I agree there, but for me, on that day at Kop Hill, it was the best Ecurie Ecosse car. To drive in the wheel tracks of Jackie Stewart ticked every box for me, and as I returned to the paddock and began to steer the Tojeiro through the packed crowds, the sound of a Merlin engine could be heard overhead.

A Spitfire from the Royal Air Force Battle of Britain Memorial Flight swept low over the fields. The crowds gasped in wonder as the legendary British fighter plane completed its fly past, and I took the opportunity to give the throttle a blip, just to remind them I was there too!

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis/Body: Tubular Steel with Aluminum Body

Wheelbase: 2250-mm

Track: 1395-mm (front) and 1375-mm (rear)

Weight: 775-kg

Suspension: Front and Rear: Independent with telescopic dampers with adjustable anti-roll bars

Steering Gear: Rack and Pinion

Engine: 3,528-cc, Buick V8

Power: 228-bhp

Carburetor: Twin Weber Type 45 DCOE

Clutch: Single-plate

Gearbox: Hewland HD5

Gears: 5 forward, 1 reverse

Brake: Discs all round

Wheels: 15-inch Magnesium

Tires: Dunlop

Acknowledgements / Resources

Our thanks go to Dick Skipworth for allowing us to drive his car and for the time spent in allowing us to peruse his personal collection and view Ecurie Ecosse films; the organizers of the Kop Hill Hillclimb for granting us permission to use their event to carry out the track test published here. We would also like to thank John Pearson for his valuable resources, and Sir Jackie Stewart for his recollections.

Autosport Magazine

Ecurie Ecosse: A Social History of Motor Racing from the Fifties to the Nineties by Graham Gauld Graham Gauld Public Relations. ISBN 0-9519488-0-6

Ecurie Ecosse: David Murray and the Legendary Scottish Motor Racing Team by Eric Dymock Paul Skilleter Books. ISBN 978-0-9550102-2-4