With the recent passings of Carroll Shelby, Roy Salvadori and Ted Cutting, all key players for Aston Martin’s World Sportscar Championship-winning team of 1959, it seemed reasonable to speak with another racer who worked in that fabled John Wyer-run team, Rex Woodgate. Woodgate is a notoriously detail-oriented mechanic who became an early collaborator of Stirling Moss and also drove on occasion. He then had a brief tour of duty as team manager for the Connaught Grand Prix team before hooking up with Mike Hawthorn’s father Leslie and taking a job with the family’s TT Garage. This led him to his tenure with Aston Martin, which in turn sent him to the USA where he eventually became the company’s North American representative. VR’s Mike Jiggle recently sat down with Woodgate to discuss some of the more memorable experiences of his life and career. [pullquote]

“Whatever job or profession you’re in, if you do a job it has to be correct and look right. What is the point of doing a job if you’re not going to do it correctly?”

[/pullquote]

VR: I’ll start with a question I ask many of those I interview, how did you get involved in motor racing?

Woodgate: It was when I found I couldn’t afford to go flying, which from a kid I always wanted to do. But really, I was always interested in bike racing, car racing and bike trials and so on and so forth. My father knew Alan Hess quite well, he was the competitions manager at BMC (British Motor Company), and apparently he asked Alan, “How’s my son going to get into motor racing?” Alan told him to try Thomson and Taylor at Brooklands. I went and had a word with Thomson and Taylors, their workshops were based inside the circuit at the Brooklands and were famous for record breaking cars such as the Napier-Railtons, in the 1930s and ’40s. After talking with them, they agreed to employ me. I was put to work on big diesel generators, but I used to try and chat as much as I could to Nobby Clark and Benny Benstead who worked on the record and racing cars. I was very interested in their racing experiences. I’m not too sure what happened to Nobby, but later I met Benny Benstead. He was working for Connaught as one of their main engineers.

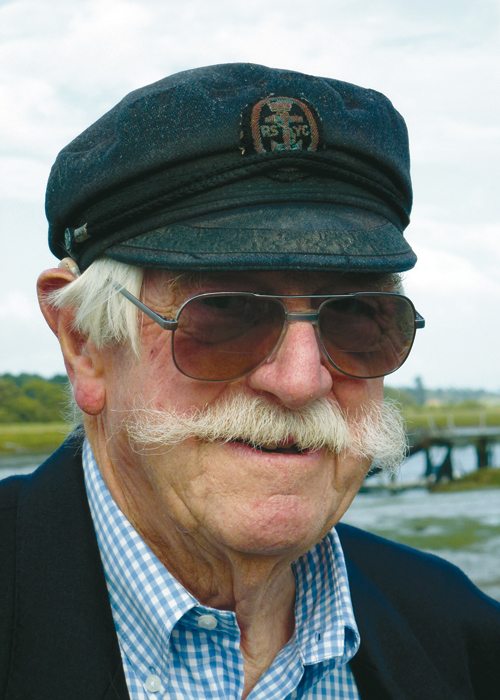

Photo: Mike Jiggle

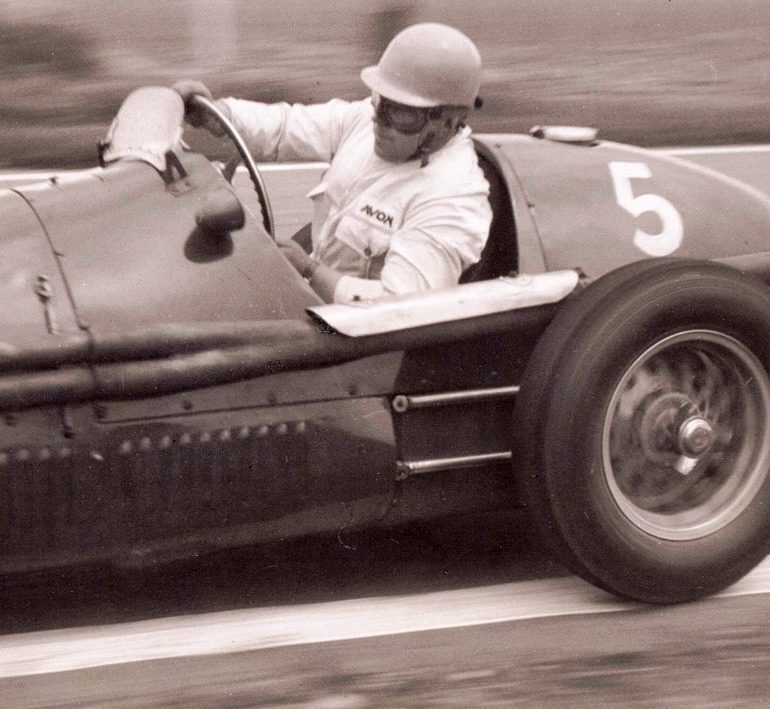

I guess it was in 1948, when Stirling Moss was running the green “anodized” Cooper, we were running the 500-cc JAP and the 1000-cc JAP engines at that time, as the 1100-cc hadn’t yet come in. My job was to look after the car, which included changing the engines back and forth at some races. At the first Goodwood meet of the year, we practiced with the 500-cc engine, Stirling came in and I replaced the 500-cc with the 1000-cc engine for the next practice. The following day it was the same job for the races. We were always very busy at meetings where we needed to change the engines; it kept us on our toes. I think we won or did very well in those Goodwood races. However, there is one thing I do remember about that weekend. The 1000-cc engine was a recirculating engine with a tank and a dry sump, whereas the 500-cc engine used to take oil in and dump it out from the bottom of the car. Well, I had a friend helping me change these engines, and I asked him to check the oil in the tank—which was a bit low. I was busy doing other things and he filled the oil tank quite full. What I’d omitted to tell him was when the engine was tested the oil in the sump would flow out and back into the tank—of course with all this added oil it was overfilled. I managed to suck the excess oil from the tank, and on noticing an empty lemonade bottle on the grass nearby I squirted it in that. I continued working on the car when Papa Moss, Stirling’s Dad, came by. He picked up the lemonade bottle and took a long swig before I could stop him. He swallowed the oil, Stirling’s mother, Aileen, shouted to me, “You’ve poisoned my husband!” I said, “There’s no need to worry, it’s just straight castor oil, it’s just been around the engine a couple of times.” The next morning I saw Papa Moss and asked how he was doing. He said, “I’m clean, clear through!” I was with Stirling for a while working at White Cloud Farm in Bray, and living in a caravan on the estate. I enjoyed my time with him. He was a good lad, but yet to make his name in motor sport.

I left because it got to the point where JAP wanted to do its own engine servicing, maintenance and development. So, there was very little for me to do. One thing I was pleased of, while working for Stirling, was the idea I had to modify the airflow through the engine of the car. I designed a cowling with an under-chassis scoop to overcome the engine overheating problems. I showed Papa Moss my idea and asked who we should get to build it. Unfortunately, he insisted Coopers would make it; much against my wishes as I felt we should have kept the idea quiet. I was really pissed off when Papa Moss had the work done at Coopers, and my reservations were proved right at the next meeting at Manx. We turned up with our cars modified, and Stirling had done a couple of laps in practice. John Cooper rushed over and when the bonnet was opened he spat on the rear cylinder head. In amazement, he said, “It didn’t spit back!” We were then aware that three additional cowlings, already in their transporter, were fitted to his works cars. Unfortunately, in the race Stirling had magneto problems, which caused him to retire and John Heath eventually won in the HW Alta.

VR: When researching, I found some editorial in a magazine that described your mechanical abilities as being “as meticulous as a nanny.” Could that be a reasonable description?

Woodgate: Yes, it could. Whatever job or profession you’re in, if you do a job it has to be correct and look right. What is the point of doing a job if you’re not going to do it correctly, or if it doesn’t look right when you’ve finished? Yes, I’m a bit bloody fastidious and finicky.

VR: After parting company with Stirling where did you go?

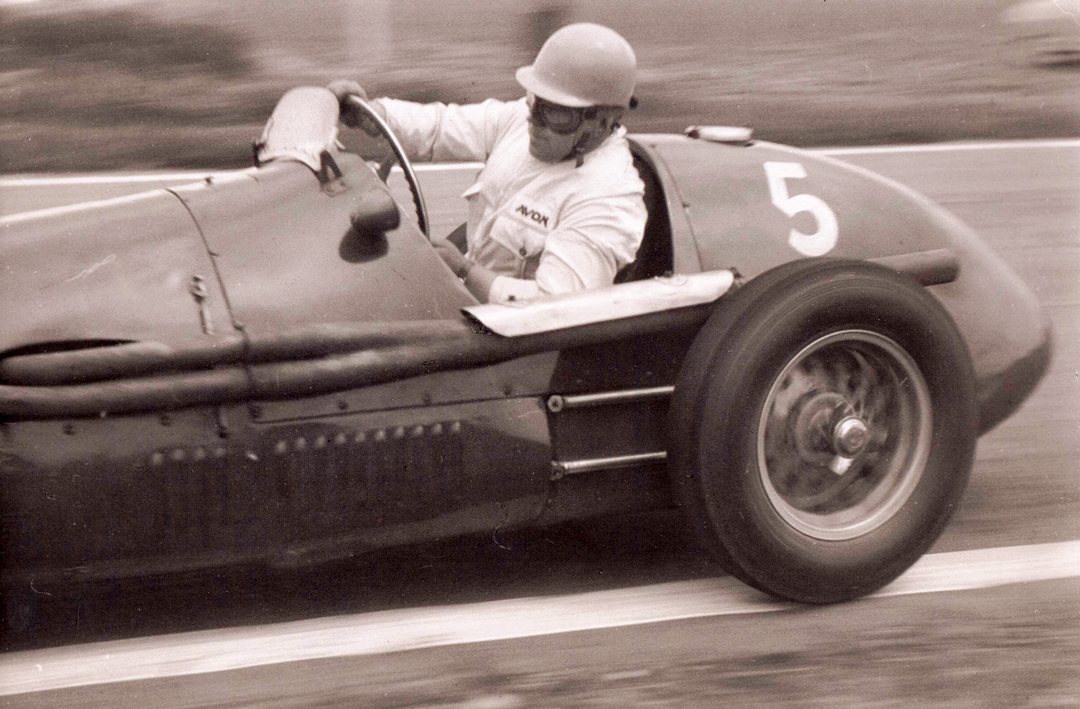

Woodgate: Ironically, I went to work with John Heath and George Abecassis. That would be in 1949, it’s where the HWMs were built and Stirling became one of our drivers. This was the first British racing team in Europe after the war, and they were really quite successful. In winter of 1950-’51, we built the first single-seaters, but I left them after the first race at Goodwood and joined Gordon Watson, who owned a F2 Alta. I drove the car on occasions when he wasn’t available.

After that I messed around a little, building cars here and there. I worked for a while for John Lyons working on his Connaught. When he disposed of that I ended up at Connaught Engineering, eventually landing the job of team manager. Of course, I think I was a little too young and naive for the post. I got on the wrong side of Basil Putt one day at Snetterton, we’d had a bit of trouble there and I gave him some “stick.” What I didn’t realize, Basil was a good friend of Rodney Clarke, founder of Connaught. After they’d had words my days were numbered.

After my problems at Connaught I had to rebuild my career, which I did at the TT Garage, Farnham with Leslie Hawthorn—I’m not too sure who suggested I go there, but that’s where I ended up. That would be in 1954, the year I married Joyce. The workshop of the TT Garage was behind the cottage offices and the long showroom. Leslie worked on his own cars for Mike to race, and also on Sir Jeremy Boles’ cars, which were for Don Beauman to race. Don was a local lad, born in Farnham, and a friend of Mike. Sir Jeremy, already racing sportscars, wanted to enter Grand Prix racing and purchased a Connaught A type; he saw potential in Don. They were reasonably successful together until Don was killed when he crashed the Connaught during the 1955 Leinster Trophy race in Ireland.

My workshop at the garage was in an end part of the showroom, which I’d sectioned off. I worked on Reg Parnell’s Ferrari 500. We had a lot of fun with that. Strictly speaking, Roy Salvadori, driving a Maserati 250F, should have beaten Reg every time, but we managed to beat him on most occasions. Reg was a great racer. After a particular race, we’d found a crack in the block, so I took the engine out and was preparing to take it back to Ferrari for repair. A couple of days before a Crystal Palace meeting Reg rang to say he’d been offered an enormous amount of money to race, so I had to put the car back together, change the axle ratios and generally prepare the car for racing. I worked all night and remember driving the car up and down Farnham High Street at three o’clock in the morning to see if it ran properly. I put it in the truck and set off for Crystal Palace. When I got to the circuit I unloaded the car, it was still warm from my testing it. Anyway, we won the race.

After another race victory at Goodwood, we stopped at a pub at Midhurst, the Spread Eagle, Les Hawthorn popped in and said to my wife Joyce, “Tell him not to drink too much, he’s got valuable cargo in the back of the truck!” On the way home we spotted Les’ B20 Lancia off the road, I can still see the car bearing the TT Garage “trade plates.” I said, “My God! That’s Les’ car.” We later realized that Les had been killed. When we got back to the TT Garage Brit Pearce drove onto the forecourt, he’d just returned from Italy with Sir Jeremy Boles’ Connaught, he was able to contact and inform the family. In the aftermath of all this I ended up working for Mike. Unfortunately, Reg’s Ferrari left Hawthorn’s to be prepared by someone in Derby.

Photo: Paul Skilleter

VR: Mike Hawthorn was really affected by the death of his father?

Woodgate: Yes, yes.

VR: Did you stay at the TT Garage long after that?

Woodgate: No, just shortly after that Mike had talked with Tony Vandervell. Tony was running the Vanwall team and suggested I contact them—which I did. They offered me £1,000 per year to work for them, a ridiculous amount of money in those days, so I took the job as manager. I didn’t stay there too long, as I wasn’t too impressed with the attitude of some of the hierarchy. Later, Reg Parnell asked me to help him with a Ferrari he’d borrowed and run at Silverstone. Reg had a word with John Wyer at Aston Martin and suggested I should speak to him. After that, I agreed a deal with Aston Martin and worked on the production DB3S cars. Part of this job was to look after the cars raced privately by a U.S. Naval Commander, Arthur Bryant, who unfortunately lost his life at Oulton Park. I think it was the one and only race I hadn’t attended with him as I was on the way down to Italy with three Lagondas. These were to be used in the making of the film Checkpoint.

I worked with another private driver, Hans Davids, who used to race D-Type Jaguars and had some success racing the DB3S. He approached John Wyer, who agreed to fit his car with a works twin-plug head, this considerably improved performance. Having done this we raced the car in Yugoslavia, at a circuit in Opatija. Franco Cortese was racing at the same meeting. It was a shocking circuit, just a road up a steep hill out of the village and a return back on a parallel road. I said to Hans, “Don’t worry about Cortese, you’ve got him. Just sit behind him and take him on the closing laps.” Despite this Hans overtook Cortese and led the race. Hans clipped the kerb, bent the de Dion axle and retired from the race. Cortese went on to win.

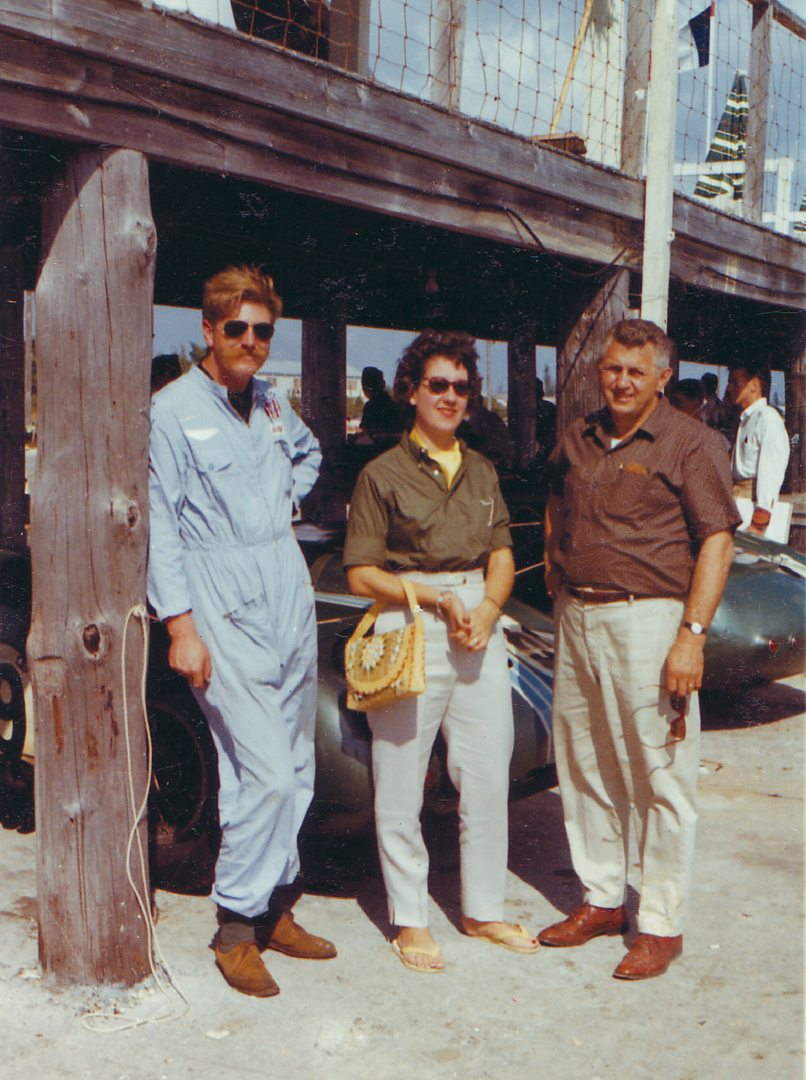

Photo: Bahamas News Bureau

I repaired the car ready to race at Zandvoort. We were up against Carel Godin de Beaufort and his Porsche. It was a foregone conclusion that de Beaufort with his works-supported car would win the race. It was to be Hans’ last race. He wanted to do well, which he did. Not only did he win, but he set fastest lap and a new record for the circuit. It was bloody wonderful! There was nothing wrong with de Beaufort’s car, Hans won on merit.

It had now got to the point where the 3S was no longer a winner and there were no private cars being raced. So, I returned to the works racing department to work with Fred Shattock on the DBR1, DBR2 and also the DBR3.

VR: You mention Wyer, who was a big name at Aston at that time. Many people have opinions about him. What was he like to work with, how did you get on with him?

Woodgate: You have to understand, things in those days were different, he was Sir to me because I was a mechanic and he was the team manager. You just knew your place, more importantly you understood he was the boss!

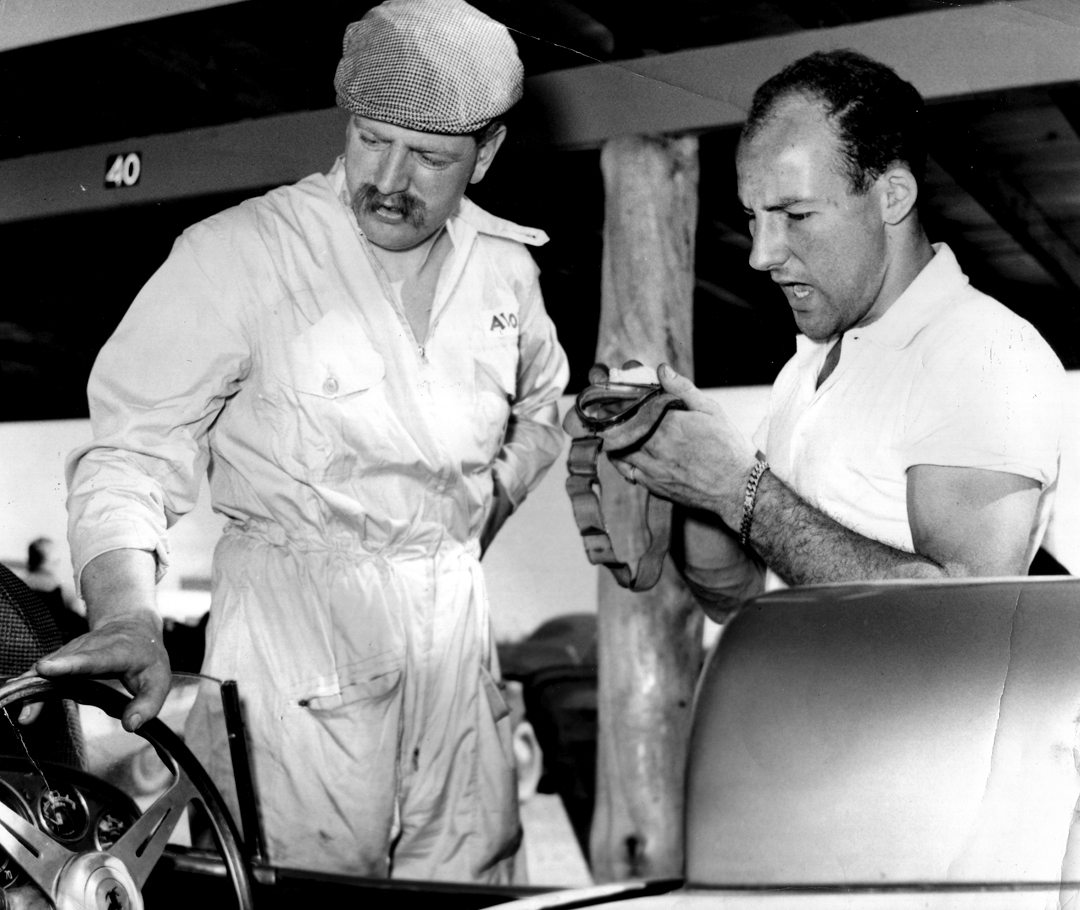

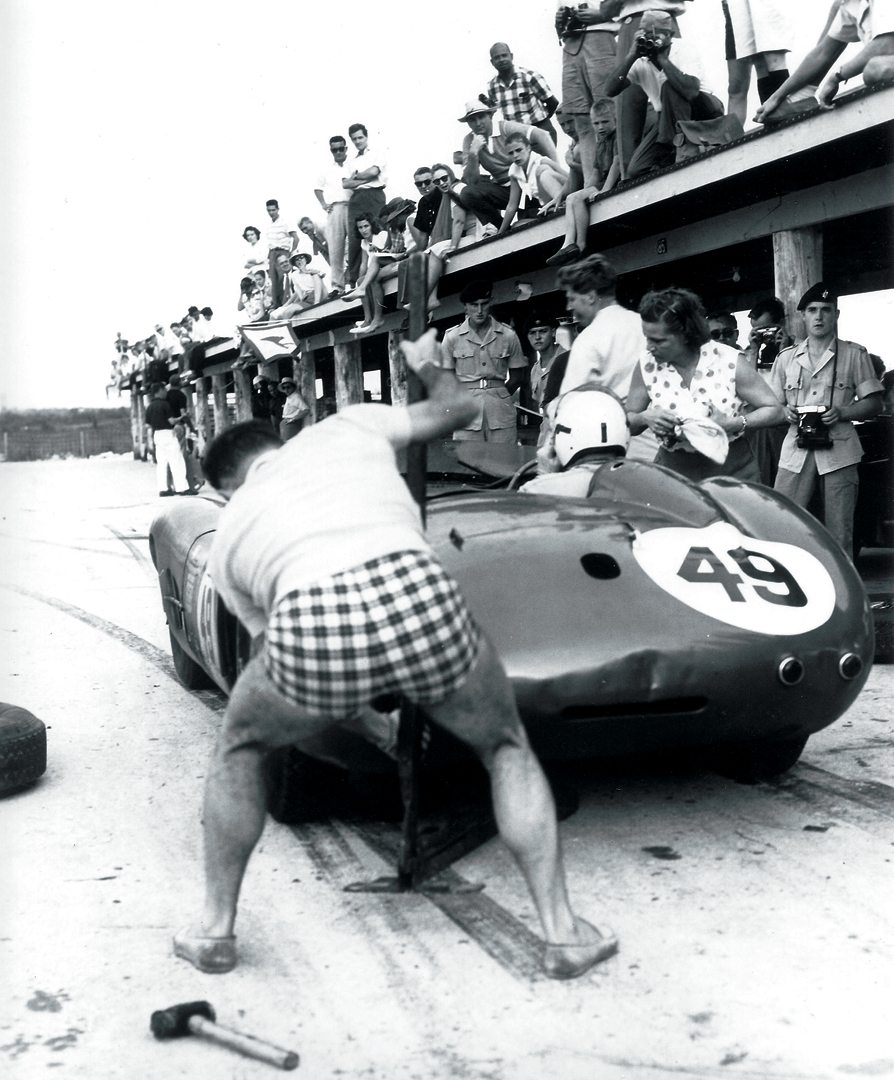

In the same building as the racing department was the R&D department and the machine shop. Seemingly, I had upset the foreman of those departments. He suggested to John Wyer that I should be fired. However, John simply told him not to be so bloody silly, as it wasn’t right to get rid of an experienced race mechanic such as me. By this time, Reg Parnell had taken over as team manager and sometime later decided to combine all three departments. My “friend,” the foreman, decided that Tug Wilson, Peter Ling, Paddy who swept up and me were surplus to requirements and we all had to go. Fortunately, Reg asked me to see him after working hours that day and offered me a job looking after George Constantine’s car in the U.S. It was the time when the DBR2 went to the U.S. Jimmy Potton had been given the job of looking after things, but apparently he wanted to return to the UK. So, Reg offered me the opportunity of replacing him. I went to the Nassau Speed Week in the Bahamas, in 1957, racing with Stirling Moss in the Aston—things had come full circle. I was working with Moss again, who by now was a world class driver. It was through this that I met Elisha Walker Jr., and after meeting him I agreed to stay in the U.S.

Photo: Woodgate Archive

VR: Can we talk about Nassau, what happened in 1957?

Woodgate: Yes, I went to Nassau in ’57, ’58 and ’59. I went over with Reg and Stirling. John Wyer joined us later. Stirling had told Reg Parnell that he didn’t think he had a chance of winning the big race, but he thought there was a chance of the car winning something. Ruth Levy had a good chance of winning the Ladies’ race; he thought she could beat Denise McCluggage. Both Reg Parnell and John Wyer thought it was a good idea too, until Ruth rolled the car in the second heat.

VR: What was Wyer’s attitude to racing in the Bahamas? I’ve read that he suggested racing there was an “end of season jamboree, noted more for the parties than the racing.”

Woodgate: I’m not sure what his attitude was. He came to the 1957 event and seemed all for it. Yes, it was a jolly. While we’d go to a different hotel every night for a cocktail party, the racing was deadly serious. However, I did hear some say that Nassau was “a bloody good fun event, but what a shame we had to bring the cars!” Seriously, most comments about the event were good. Teams would turn up after a good season of racing with whatever car had made it through, it was a time when drivers could “let their hair down” a bit and enjoy a more social side of the sport, rather than focused competition—although in the races no one wanted to lose.

VR: You mention the Ladies’ race, Ruth rolled the car?

Woodgate: In the Ladies’ race Denise McCluggage drove a Porsche 550RS and Ruth Levy drove the Aston Stirling had driven. Denise and Ruth were the top U.S. lady racing drivers at that time; they were very feisty. There were two heats, and Denise won the first of the heats by a narrow margin. The accident happened, as you say, in the second heat. The two ladies were out in front swapping the lead. On the fourth lap they entered the British Colonial Loop. Ruth was in 2nd place and tried to out-brake Denise, but got caught out by the tight corner. When Denise braked it was too late for Ruth, she’d lost control of the Aston and rolled it. Luckily she was thrown out of the car without any serious injury—other than dented pride. However, the car was too badly damaged to race again.

Photo: Bahamas News Bureau

VR: I’ve read that Stirling wasn’t too displeased, his car was damaged as he was finding it hard to keep up with the Ferraris, so he was offered a Ferrari to drive in the Nassau Trophy and won?

Woodgate: I’m not so sure about the first part of your question, but yes Stirling drove a Ferrari 290MM that had been loaned to him by Jan de Vroom. I think Luigi Chinetti prepared the car—both he and de Vroom were friends and, of course, part of NART, which was very much in its infancy then. Moss won the race, Shelby was 2nd and Phil Hill 3rd.

VR: A certain Ricardo Rodriguez finished 8th. He was so young one author described him as “only being able to produce a shavable beard once a week?”

Woodgate: I wouldn’t know about his shaving habits, but I do recall there being a tremendous amount of discussion as to whether he was old enough to race—he was just 15 years old. I didn’t really have a view about his age, he was just a bloody good driver—just phenomenal. Looking back, personally, I thought Ricardo was better than Pedro—sadly, neither lived long enough to show their full potential.

VR: In 1958, Nassau became embroiled in the politics of SCCA and USAC. Only amateur drivers were allowed to race, did that affect you?

Woodgate: Not at all, Stirling didn’t drive that year as he wouldn’t be paid starting money. He was in Nassau and joined our team. He helped me in the pits when the long exhaust system broke on the DBR2 and had to be secured with strong cable. I was assisting George Constantine, whose car was entered and financed by Elisha Walker Jr. In fact, George had campaigned a full season of racing with that car in ’58. I think George was able to win one of the minor Nassau races in 1958, but it came good for him in 1959 when the professional drivers came back. He won the Nassau Trophy and the $13,000 prize money.

In America, at that time, there weren’t any “sportscars” as we called them in Europe. Americans called their cars “sporty cars,” and they were all amateur drivers. Their racing was something quite different to Europe, they had midget racing, dirt track, short track on dirt and boards, and Indy cars. All their racing was geared to a ladder of competence that would ultimately lead them to the pinnacle of their sport, which was Indycar racing and their blue ribbon event—the Indy 500. So, I think, 1958-’59 was the dawn of proper professional sportscar racing on a par with Europe. As professionalism grew in the U.S., so did their cars. They quickly caught up with the European sportscar scene, too.

VR: As you have already said George won the Nassau Trophy in 1959, wasn’t that the coveted trophy of the races there?

Photo: BRDC

Woodgate: Yes, 1959 was very good. George was a very accomplished racer and won many races that season. Aston Martin had sent their highly developed “works” car over with Stirling as driver. I had worked all season with George and Elisha, preparing and developing the car myself. The Nassau Trophy race didn’t turn out too well for Stirling, I think there was a problem with the battery and Stirling got sprayed with acid. Eventually he retired, or at least finished in a very minor place, whereas the car I’d prepared came 1st with George at the wheel. It was so pleasing for me to think I’d prepared the car that had beaten the works car. That was the year both George and I were awarded trophies by the New York Times; George for best U.S. Racing Driver and me for best mechanic.

VR: 1959 had been a good year for the works Astons as they’d won at Le Mans and won the sportscar championship. I notice Roy Salvadori missing from the list of drivers?

Woodgate: I don’t know too much about Roy, I can’t recall. I don’t recall Tony Brooks coming to Nassau either, but Carroll Shelby had already competed there.

VR: Was 1959 your last year at Nassau?

Woodgate: No, I really wanted to run DBR3 in 1960, a real pet car of mine. It was a DBR1 with a bigger 3.9-liter engine, which became 4.2-liter, but had oil scavenge problems. Stirling ran the car once, set fastest lap, but had to retire as the scavenge pump failed and the bearings seized up. R3 was one of my babies that I wanted to develop, but by then new regulations came in and limited the engine size. Aston Martin became involved with their Grand Prix car and competing in Formula One. Everything else took a back seat.

I went back in 1961 and worked with Bob Grossman, who drove a Ferrari 250GT SWB. The first three in the big race were Gurney, Penske and Pedro Rodriguez, Bob finished just outside the top ten. Not too bad given the opposition, Graham Hill finished in the top five, too.

I worked with Bob for a couple of years. Then I worked for another Brit, who I’ll just describe as a “loveable crook,” or “scurrilous rogue,” all he wanted me to do was cobble up vintage cars—I didn’t last long with him!

Soon after, John Wyer approached me with a proposition. He wanted me to become the Aston Martin representative to cover the U.S. and Canada. I worked out of J.S. Inskip Inc. in New York City. Subsequently, convincing the factory that we should do our own importation and distribution, we set up Aston Martin Lagonda Inc in The King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. I did that for some years. When I eventually returned to England, I set up my own engine business in Blisworth, Northamptonshire. Later I relocated to a unit at Silverstone Racing Circuit. I continued to prepare engines and my son joined me to prepare chassis. He still runs the business today.