A number of years ago, in the early days of Vintage Racecar when I think we were still in “black and white,” the editor/publisher, Casey Annis, whom you now all know well, came to England to have a look at what the new “European team” was doing. I took him to a VSCC race meeting at nearby Silverstone for his first look at English motor sport.

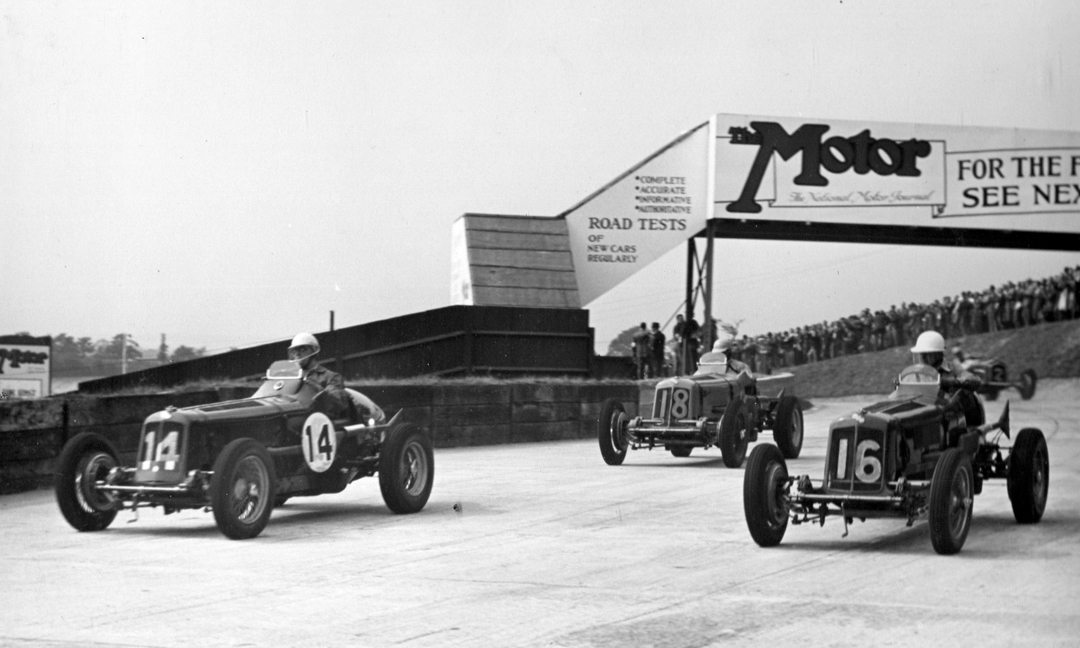

This was just an “ordinary” historic race meeting, and on the program was an all-E.R.A. race, where I believe all but one of the original production run of these cars was on the grid. That in itself was pretty spectacular; how many manufacturers of any size have had all their cars on a grid at the same time? The answer, I am quite sure, is none.

Photo: Peter Collins

The conditions were wet and nasty, the usual stuff for that time of year—and a lot of other times of the year as well! When the pack came ’round Woodcote Corner at the end of the opening lap, all the drifting lead cars pointed straight at the pit wall where we were standing, Mr. Annis knew that he was in for something rather special. At the end of 15 laps of the most hard-fought race by a pack of then 60-year-old-plus cars that you can possibly imagine, the visiting Editor had seen the most stunning display of motor racing. I know he will insert a comment here! [Editor’s note: In fact, it scared the crap out of me as I was certain that I would imminently be picking pieces of Martin Stretton’s E.R.A. badge out of my teeth!]

In Peter Hull’s little book Racing An Historic Car, Hull says time and again just how hard E.R.A.s were driven in historic racing over a period of several years. That book was written over 50 years ago, and the same cars—all of them—are still out there at it today, now over 75 years old! We may be a bit overdue in featuring E.R.A., but I think it has been worth the wait. All of these cars are visceral and exciting. R11B, one of the best, was simply outstanding.

The E.R.A. background

This is a book in itself, and one that, fortunately, has been written several times in various guises, though the continuing strength of the E.R.A. following among both old hands and younger historic enthusiasts means that interest in the marque has never been lost.

The Right Honourable Earl Howe wrote the preface to John Lloyd’s 1949 The Story of E.R.A., and Howe’s sentiment reflected a widely held view of the early E.R.A. (and later BRM) effort: “It is a story which I know will make an instant appeal to all who believe in private initiative, backed by high endeavor and inspired by the farseeing determination of one man to put Britain and British Products in the very forefront of International Competition.”

Howe voiced what many enthusiasts felt at the time, in that immediate post-war period, similar to the feelings that were about when E.R.A. started up in 1933. The view was that something was needed to bring back British dominance in sport, as well as in other areas, and there was a patriotic fervor behind the pre-war birth of E.R.A., wanting something to beat the dreaded foreigners, particularly the Germans with their highly financed Mercedes and Auto Unions. It is always of interest to me in reading about this period that those who wanted something to rival what the Hitler government did in motor sport rarely condemned the reasons and objectives of that regime!

When Howe refers to the one man behind the inspired E.R.A. many today will think that man was Raymond Mays, but he was in fact talking about Humphrey Cook. It was Mays who was looking for a means of competing with the big European teams in the early 1930s, as hardly anything could compete with the European manufacturers in the Grand Prix races of the time. Then voiturette racing was created mainly by race organizers to support the Grand Prix events, and occasionally to take part in those races. Voiturettes were essentially smaller versions of the GP cars, limited to 1500-cc. Mays had been campaigning a much-modified and very quick Riley, and he could see this as something that could form the basis of a genuine English voiturette.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

English Racing Automobiles was set up in 1933, and Mays secured backing from Cook, a successful and wealthy businessman who had raced Aston Martins and Vauxhalls at Le Mans and Brooklands. Mays always “fronted” E.R.A. as a patriotic effort, and fans remain quite sensitive to criticism, but a longer historical perspective that includes the BRM years makes it clear that Mays was as enthusiastic about his own interests and image as he was patriotic. More recent accounts of BRM show how these interests often interfered with the success of BRM, though that seems to be slightly less the case in the pre-war days.

Humphrey Cook, after whom the R11B you see here was nick-named by its first owner Reggie Tongue, put up almost all of the required capital to get E.R.A. going. Though announced in 1933, the first car did not appear until midway through 1934. The early design was in the hands of Reid Railton and young Peter Berthon, and it was fairly conventional with a channel frame chassis that would accept engines of 1100-, 1500- and 2000-cc. It had a torque-tube style transmission, and the gearbox was in unit with the engine, semi-elliptic front and rear suspension, friction dampers, Girling brakes and Dunlop 16-inch tires. The gearbox was unique in that it was what was then called an Armstrong Siddeley Wilson “self-changing gearbox,” what we now refer to as a pre-selector box. The engine was very much based on Mays’ rapid “White Riley,” which was a very quick six-cylinder unit producing 150 bhp.

The first car was R1A and the first A series cars were built in 1934-’35 with a Murray Jamieson supercharger. R1A was late in appearing, but finally ran very quickly with Mays and Cook behind the wheel at the British Empire Trophy race. Mays established a number of records at Brooklands that year, set fastest time at Shelsley Walsh and won the Nuffield Trophy at Donington. R2A appeared in July for Cook, often with a smaller 1100-cc engine, and Cook likewise established many class records. R3A emerged in August with a 2-liter engine and Mays took the World Standing Kilometer record with it and did well in the Eifel voiturette race at the Nürburgring. R4A was the first car built for a private owner, South African-born Pat Fairfield. It was completed in April 1935, first with an 1100-cc unit later replaced with a 1500, and in 1936 raced in the E.R.A. works team.

The B-Type

The B-Type, which first appeared in 1935, was in fact quite similar to its predecessor, with attention paid to detail to make it more reliable as a “customer car.” The later C and D Types would again be updated and modified versions of the A and B Types. R1B went to Richard Seaman who would later drive for Mercedes-Benz. Seaman took wins with R1B at Pescara, Berne and Mazaryk in 1935. By now the E.R.A. factory was very busy. It was essentially based in Raymond Mays’ garden, eventually extending across the road to new premises that became his car dealership, and these were the facilities that later expanded into the BRM works. R2B was commissioned for Prince Chula of Siam for his cousin, Prince Bira, to race. This car, still known as Romulus, enjoyed a spectacular career, winning races at Monaco, Brooklands and Picardie in 1936, the Isle of Man, London and the Imperial Trophy in 1937, and several more major races in 1938 and 1939.

R3B was raced by Mays and Cook before going to the French driver Marcel Lehoux who was killed in it. It was dismantled and used for parts, and is the only original car not to survive. R4B was a works car, the most successful of the works entries driven by Mays, and at various times it used all three sizes of engines—and had a “self-locking differential.” It won 15 important races in period, and Mays eventually bought it to run privately. R5B was also commissioned by Prince Chula and, nicknamed Remus, driven again by Prince Bira. When owned by Tony Rolt, this car was modified by Freddie Dixon with a Riley crash-type gearbox. Rolt won the 1939 British Empire Trophy with it.

R6B, R7B, R8B, R9B and R10B were all driven by well-known drivers of the period—Dr. Benjafield, Ian Connell, Arthur Dobson, Earl Howe, Richard Ansell, Shaw Taylor, Peter Whitehead and Peter Walker—recording wins not only in Britain and Europe, but also in South Africa and Australia.

Photo: R.E. Tongue Collection Courtesy David Morris

R11B – Humphrey

R11B, the car you see here, is rather extraordinary in a number of ways. Lloyd’s 1949 book modestly credits it with winning the 200 Mile Race at Cork in Ireland, and that it was owned by R.E. Tongue and Hon. Peter Aitken. In fact, R11B is probably the most written about of all the E.R.A.s, as it was later owned by Douglas Hull whose brother dedicated most of one of his books to it. The thing that most impressed me, however, when I came face to face with it and was about to get in it, was that this was a 150 mph car that you sat on rather than in! More about that in a minute.

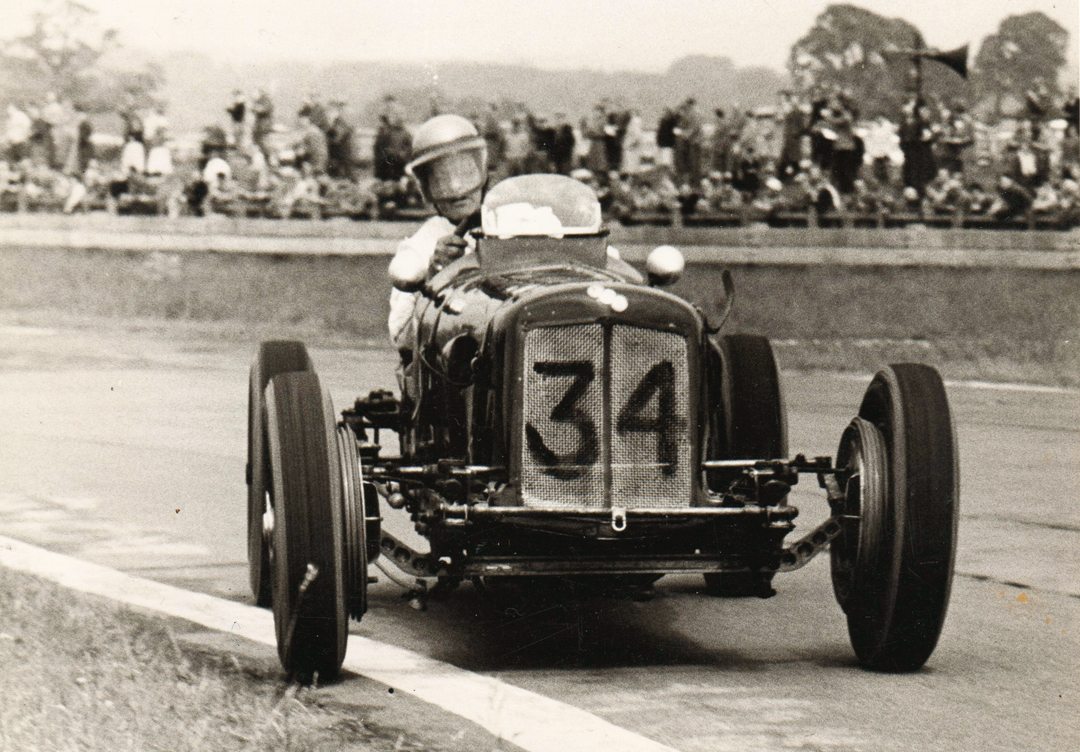

Reginald Ellis “Reggie” Tongue was born in 1912 and, when his father died while he was still at school, he persuaded the trustees of his father’s estate to advance him money to buy a Riley that he raced. He then bought Richard Seaman’s MG Magnette. He bought R11B new, in dark green with the 1.5-liter engine, in 1936. He quickly won his class in a French hillclimb, and the Inter-Varsity Championship at Brooklands. A major win came at the Cork Grand Prix in Ireland, followed by good placings at Berne, Picardie and Donington. He had an ambitious program for 1937, coming 3rd behind Bjornstad’s R1A and Rene Dreyfus’ Maserati 6CM at the Gran Premio del Valentino in Turin. He was 8th at Posillipo in Italy, both of these voiturette races supporting major Grand Prix events. He was 4th in the Light Car Race at Douglas in the Isle of Man only a few seconds behind the leading trio of Bira, Mays and Pat Fairfield. He was 5th in Florence where Dreyfus won, 4th in Milan which was taken by Siena, and 3rd behind Cook/Mays sharing R4B and Charles Martin’s R3A at Albi. He had good results in domestic events at both Donington and Brooklands. He had top-three results at Brooklands again in 1938 before selling the car to the Honorable Peter Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook.

Photo: R.E. Tongue Collection Courtesy David Morris

Sales of B-Types had been slow at the end of 1935, but picked up the following year. The works cars were less successful in 1936, and were considered poorly prepared and unreliable, the new Zoller supercharger tried by Mays being powerful but often failing to last. Humphrey Cook was becoming disillusioned by the end of 1936, but was persuaded by Mays and Berthon to invest in the development of the C-Type with the Zoller blower, new connecting rods, independent front suspension and a new frame design. This car dominated 1500-cc racing in 1937, but against Cook’s wishes was not offered for sale. The D-Type was an evolution of the C-Type, and the remaining funds went into producing a Grand Prix car supposedly capable of racing against the Alfa Romeos. This project broke the bank, and when the new car was a failure Cook sold his interests in 1939. The same lack of solid business thinking by Mays and Berthon, however, would be carried over into their next project—BRM.

Meanwhile, Aitken did nine races in 1939 before the outbreak of war in Europe, six at Brooklands, and one each in South Africa, Crystal Palace in London and at Donington. He won the Easter race at Brooklands, and was 2nd in the Grosvenor Grand Prix in South Africa. In this last race Aitken drove very well in R11B to follow Cortese’s Maserati home, while Taruffi, Earl Howe, Peter Whitehead and Villoresi all retired. Ten E.R.A.s appeared for the Nuffield Trophy race at Donington, Bira winning in R12C from Mays in R4B, Whitehead in R10B with Aitken 7th. It was toward the end of 1939 that the E.R.A.s and Maseratis came up against the Alfa Romeo 158—and found they had no hope of beating it!

Photo: R.E. Tongue Collection Courtesy David Morris

After the war, R11B emerged in the hands of Reg Parnell, who was spending much of his time racing Maseratis, and slightly later the E.R.A. E-Type. A number of E.R.A.s came out to contest the voiturette races in Europe in 1946 and 1947, and as many as ten showed up for the major British races. R11B saw little action during this period, taking 5th in the Ulster Trophy in Ballymena in the hands of Cowell and Watson while still being run by Reg Parnell. In 1948, the car was sold to Peter Bell who already owned R5B. The main intention was for it to be raced by John Bolster, a noted driver who would become one of the best known motoring journalists of the 1950s and 1960s. Bell would occasionally drive R11B himself, and won his first event at a sprint meeting in 1948. The car had by then been equipped with an original 2-liter engine which it still has today.

In 1948 it won the Ladies Class at both the Boness and Bouley Bay hillclimbs driven by Sheila Derbyshire, while Bolster had 2nds and 3rds at Shelsley Walsh and Goodwood, Parnell himself scored good placings at Bouley Bay, Boness and Shelsley, while Bell ran at sprints and the Brighton Speed Trials where he was 6th. Roy Salvadori was to drive it at the Dutch Grand Prix, but did not start after an accident in practice. St. John Horsfall took 2nd at the British Empire Trophy on the Isle of Man in 1949, behind R14B raced by Bob Gerard. Bell entered Horsfall for the Dutch Grand Prix where he managed 6th in his heat—won by Villoresi’s Ferrari 125—but failed to start the final when a piston failed. Young Stirling Moss was the star of this meeting, winning the 500-cc race. Tragically, Horsfall struck a bale during the International Trophy race at Silverstone in August and was killed when the car overturned.

In 1950, Ken Wharton began his association with R11B driving for Bell, winning his class at Shelsley Walsh in the first event of the season. The car appeared again at Shelsley later in the season with Wharton taking 3rd-fastest time of the day, and Bell drove it at the Brighton Speed Trials once again. In 1951, R11B had a very busy season, doing 15 events. Wharton was contesting the British Hillclimb Championship very seriously in both the E.R.A. and a Cooper-JAP. He took four wins in R11B and won the Championship. He also won races at Castle Combe and Snetterton, and had fastest time at the international Freiburg Hillclimb and the Vue des Alpes Hillclimb, with good finishes at several other international hillclimbs. Wharton did nine hillclimbs in 1952, with five victories, and enjoyed a similarly successful season the following year. Michael Christie drove R11B for Peter Bell through 1954 and 1955, and then it was sold in 1956 to John Broad.

A great deal of work was done for Peter Bell by George Boyle who lightened the car and moved its engine back in the chassis to improve the handling. It was fitted with a smaller radiator and fuel tank, the large oil tank was removed and it was converted to a wet sump setup. It was still fitted with the large 140-mm Murray Jamieson supercharger. Roy Bloxham drove the car while it was in the ownership of Barrie Eastick in 1957, but it was then sold to Douglas Hull in 1958. Hull did some 15 races, sprints and hillclimbs in 1958, and 17 events in 1959, with numerous successes, including winning the Richard Seaman Trophy.

In 1962, Humphrey went to Martin Morris and it has remained in the Morris family to the present day. Martin Morris became a regular winner of the Seaman Trophy with a record of 10 wins, during which time it became one of the most successful machines in British historic competition, also winning at Monaco in 1979. Martin’s son David took over the running of the car in the 1990s, again winning the Seaman Trophy at the VSCC British Empire Trophy meeting at Donington in 2002. The original E.R.A.s have been a major part of UK historic events for many years, with an incredibly devoted group of people owning and looking after them, and they show few signs of ever slowing down. R11B has seen so much action over its 76 years that it deserves a book on its own—hopefully if you watch this space you might see that happen!

Behind the wheel of Humphrey

It’s superlative time again.

Of all the really excellent machinery I have had the great good fortune to experience, Humphrey, R11B, is without question the most visceral, and creates the greatest sense of anticipation, a distinct aura of anxiety. It abounds in hair-raising features, makes incredible noise and reeks of history. This car has seen more motor racing than most of us have altogether.

Photo: C. Dunn

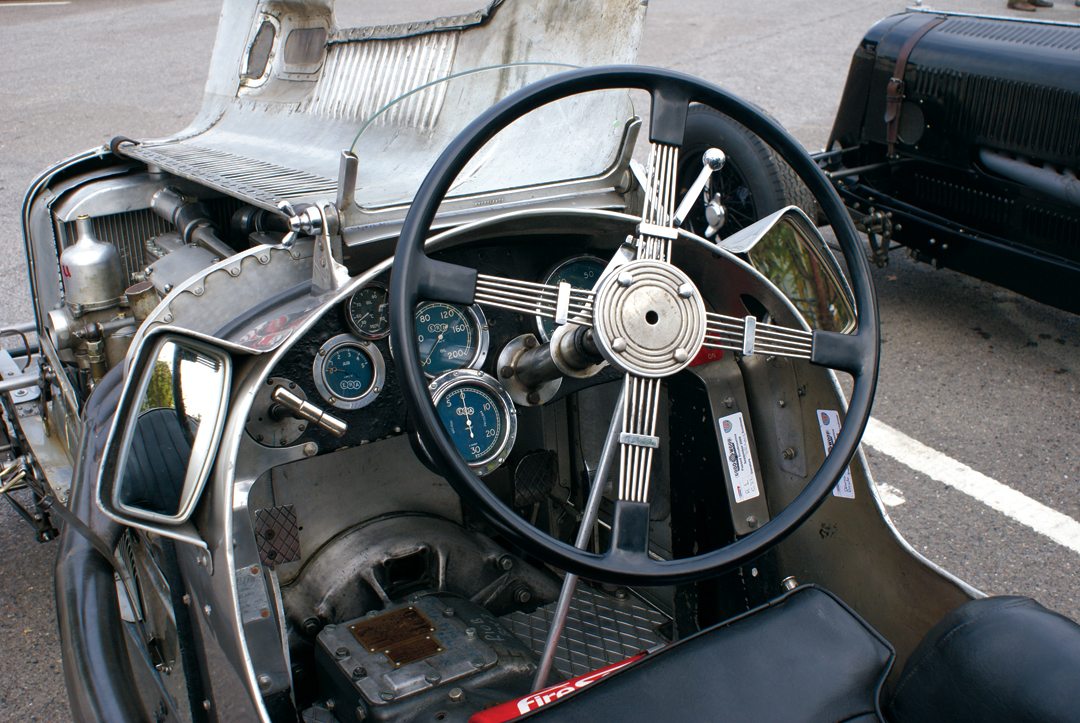

The venue was the Goodwood Revival. You are all familiar with how this event has become a step back into the past. The huge crowd is in period attire. The spectator areas are bursting with knowledgeable people. On this occasion, they are awaiting a rather special event: the bulk of the existing E.R.A.s are going out together to show themselves to the vast gathering. R11B’s owner David Morris has kindly offered me the chance to replace him behind the wheel for what will be some quick and very nostalgic laps of Goodwood. Over the last two days I have sat in the car numerous times to get the feel, to get to know Humphrey, to avoid the panic that comes with jumping into a new car. We went through the warmup procedure and the reasonably “busy” cockpit, with special attention given to the pre-selector gearbox.

The cockpit is dominated by the large four-spoke Blumel art deco steering wheel and the unique to R11B gear-change mechanism, a work of art in its own right. Pre-selectors come in varying styles and this one is, thankfully, straightforward. Some are on a horizontal plane looking somewhat like coffee grinders, but this is vertical with a lever that is just moved up and down to “pre-select” the gear, with the actual change taking place when you engage the clutch. This takes some getting used to, but at least with Humphrey you are always clear which gear you have selected. There are five gauges, including one for the boost from the very impressive supercharger.

Photo: Guy Griffiths

It is a very comfortable car to sit in, but you do feel very much that you are on it rather than in it. Fortunately, once the business gets started, you don’t even think of that, as all the attention is on getting it going, and managing a prodigious amount of power.

The time approached for E.R.A.s to go out onto the high-speed Goodwood track. The car is first warmed up with the wheels off the ground, and there is no on-board starter, so when it is time to go, the pushing crew comes out! To add to the excitement, having tried to locate myself toward the end of the string of cars about to leave the assembly area, the car in front was likewise being push-started. People are easily mesmerized by these cars, including one of the pushers of the car in front. “My” crew had already started heaving the Humphrey into action when I realized the man in front had just stopped and then was hurtling backward over my front wheel onto the grass. A quick glance sideways saw him staggering to his feet—he later came and apologized for being run down by me!

Humphrey was quickly into his stride, up to second and third gears quite quickly, and easing gently through the fast right-hander for the first time and then up to fourth down to Fordwater and St. Mary’s and then third for Lavant. The braking was immediate and stable—no pull, no fuss, all very neatly done—then there’s the exhilarating blast up the Lavant Straight, which is not straight, into the tricky and quick right-hander at Woodcote and the run to the Chicane. I was impressed with the smoothness and ease of the gearbox. I’m not at the stage where I feel comfortable selecting the gear and then leaving the change until the last minute—that comes with experience—so I used the ’box in the “normal” fashion. Acceleration is just short of blinding. It comes with gusto and noise, the six-cylinder screaming away as the revs rise, a real sensation of picking up speed. Down to Madgwick again, and this time holding fourth gear, entering the double-apex bend from the left and minding the bump on the inside, then hard on the throttle to Fordwater. This is, essentially, flat, and Humphrey needs to be set up in advance—it’s tricky, the tail hangs out a fraction. Down to the right before St. Mary’s in third and accelerating through the left of St. Mary’s and again setting up for bit of a slide through the right at Lavant to get maximum revs up the long “straight.” To my surprise, I’m catching the field, and next time past the pits, there is the reward of overtaking in front of a full grandstand—nothing like it, nothing!

The rest of the laps are devoted to getting the corners right, to feel what it’s like to drive this much power while being so exposed to the elements. Humphrey is bloody quick, but with all that, obedient and manageable, the front and back ends behave themselves, there’s lots of feel, the brakes are excellent. It is the ultimate pre-war driving experience. My existing respect for E.R.A. got a further boost. Long may they continue.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: (B-Type specifications as in period)

Wheelbase: 8 feet 2 inches

Track Front: 4 feet 4.5 inches ; Rear: 4 feet

Weight: 1624 pounds

Engine: 6-cylinder, 2 valves per cylinder, detachable aluminum head

Bore and stroke: 57.5 mm x 95.2 mm

Capacity: 1488-cc (or 2.0 liters)

Power: 180 bhp at 6500 rpm originally

Supercharger: Roots-type Jamieson blower

Suspension: Front and rear: semi-elliptic

Gearbox: In unit with engine 4-speed Armstrong-Siddeley pre-selector

Acknowledgements/Resources

(I can’t thank David Morris enough for his generosity and help at Goodwood and ever since. Thanks also to John Pearson for helping to get it to happen.)

The E.R.A. Club Newsletter Spring, 2010

Hull, P. Racing An Historic Car Motor Racing Publications London 1960

Lloyd, J. The Story of E.R.A. Motor Racing Publications Abingdon-on-Thames UK 1949

Venables, D. The Racing Fifteen Hundreds Transport Bookman London 1984