Pat Flaherty’s time on racing’s grandest stage may have been all too brief, but he managed to make it count.

When a slim, red-headed Irish-American named Pat Flaherty donned his white helmet with the big green shamrock on the front and climbed into A.J. Watson’s brand-new pink and white roadster at Indianapolis on May 30, 1956, he was making only his seventh start in an Indycar, his fourth at Indy. Having set new one- and four-lap track records in qualifying, he did so from pole position, and would lead 127 laps in the John Zink entry that Memorial Day to earn his face a place on the Speedway’s famous Borg-Warner Trophy. He also wrote his name in racing’s history books as the first winner of an Indianapolis 500 sanctioned by the United States Auto Club.

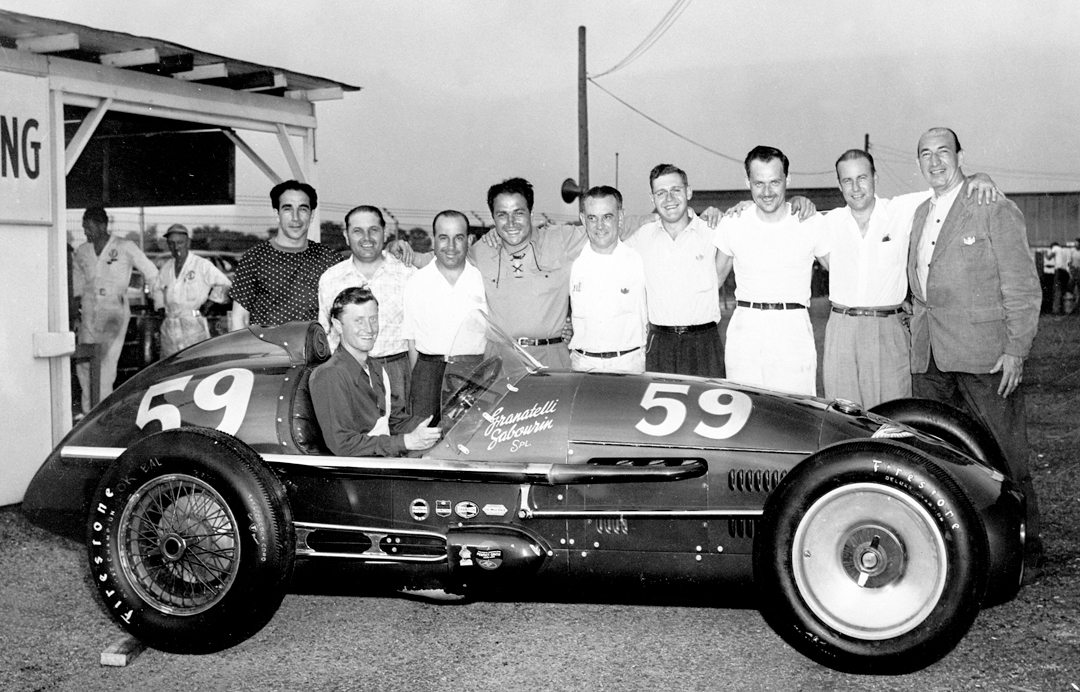

George Francis Patrick Flaherty was born in Glendale, California six days into 1926, a bit less than five months before Frank Lockhart won the Indianapolis 500 on his first attempt. Growing up in The Golden State, he served as an Air Force cadet during World War II, before learning to race in hot rod track roadsters there in 1946. He moved to Chicago in ’48 to race with Andy Granatelli’s Hurricane Hot Rod Association. There, driving those same track roadsters, he dueled with fellow future Indy stars Jim and Dick Rathmann and Don Freeland on a quarter-mile oval laid out inside Soldier Field.

He first tried Indianapolis in 1949, but failed to qualify. His rookie start there came the next year, driving Granatelli’s Sabourin Chiropractic Special, a Kurtis-Offenhauser, to 10th place in the rain-shortened race, and there was talk afterward that he’d been saving something for the last 100 miles. He spent the next two years under suspension by the American Automobile Association (AAA) for running what then were considered to be outlaw races.

Returning to Indy for 1953 he qualified only 24th in Pete Schmidt’s red Kurtis-Offy, but quickly worked up to 5th on a swelteringly hot and humid race day that forced more than half the men in the 33-car field to call for relief drivers. On the 116th lap, however, he hit the third turn wall nearly head-on, sustaining a concussion that curtailed his season. Fortunately, minding the store at the tavern he owned on the corner of Irving Park and Kedzie, 30-some blocks west of Chicago’s Wrigley Field, kept him occupied during his recovery.

He tried to come back in ’54, but couldn’t get Dunn Engineering’s modified Kurtis roadster up to qualifying speed. He jumped into the Shouse Motors Kurtis, which was powered by a downsized version of the Chrysler Hemi V8 (see sidebar), but it wouldn’t go fast enough either. Ultimately settling for a relief driver’s role for the 500, he took over for Jim Rathmann in Ed Walsh’s Bardahl Special at half distance, but then crashed the black Kurtis-Offy 15 laps later. He entered three other races with the Dunn car that year, but could qualify only at Milwaukee, where he started 10th and finished 12th, three laps behind winner Manny Ayulo.

Sticking with the Dunn team for ’55, Flaherty logged another 10th at a somber Indy 500, then recovered from an early spin that dropped him to 15th to finish 3rd the next week on the freshly paved Wisconsin State Fairgrounds Mile. He returned to Milwaukee in August to record his first Indycar win in a grueling 250-miler after qualifying 2nd and running near the front all day. He led 99 laps that afternoon and overcame both a stern challenge from Art Cross in Pete Schmidt’s car and a slipping clutch of his own to take a victory that surprised almost everyone. At season’s end he ranked 8th in the AAA point standings.

All Change for 1956

Following the death and destruction that decimated motor racing worldwide during a horrendous 1955 season, the AAA abandoned its involvement with the sport. This prompted Indianapolis Motor Speedway owner Tony Hulman, intent on maintaining his 500-mile race as “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing,” to create USAC. He also laid fresh asphalt over most of his four-cornered 2.5-mile oval, leaving the track’s original brick surface intact only along a portion of the main straightaway. It would also be the last race served by the Speedway’s famous old race control Pagoda, due to be replaced by a modern glass and steel tower later in the year.

Those weren’t the only noteworthy happenings, however. After winning at Indy and sweeping to the ’55 championship in John Zink’s pink Kurtis, Bob Sweikert decided to leave the Watson-led team—apparently over Zink’s plan to take out a key-man insurance policy on him. Flaherty was thus offered perhaps the choicest seat around, driving the very first of Watson’s famous roadsters. Although he’d initially hoped to remain loyal to Harry Dunn, Pat was ultimately convinced by his older brothers that he would be a fool to pass up Zink’s offer.

Flaherty’s signing for the defending champion team hooked him up with Watson, a man just beginning to craft his own legend as a car builder, but one who had long been aware of Flaherty.

“I first noticed him racing track roadsters, ’25 Ts and ’27 Ts, on the West Coast,” notes Watson. “He used to run Bonelli Stadium and all those short tracks out there, and that’s where I started, too. He won a lot of races there. He’d been driving for Dunn Engineering and won a couple of races with them, and I always knew he was good, so when we lost Sweikert I said to Zink, ‘Let’s hire him,’ and we hired him away from Dunn.”

Still, despite stepping into perhaps the premier Indy ride, Flaherty initially found adapting to the new lightweight roadster design difficult, as he had to unlearn some of the tricks that had helped him carry the Dunn car into contention. The major problem seemed to be that he believed he needed to brake for the Speedway’s big left turns.

“We ran a lot of miles in practice and ran all week,” recalled Watson. “Then Zink finally came in for qualifying and said to him, ‘Dammit, you’re just gonna have to quit driving with the brakes; just go down in there and back off at the starting line if you have to, but don’t use any brakes and you’ll be all right.’ And that’s how he started driving. It turned out pretty good; he sat on the pole.”

Basking in the confidence of discovering the “secret” to Watson’s new car, Flaherty dominated the race, even though he didn’t lead much in the early laps. As the DeSoto pace car pulled off and starter Bill Vandewater waved the green flag, old buddy Jim Rathmann jumped his Lindsey Hopkins Kurtis into the lead from the middle of the front row. The blue and orange car led the first three laps before yielding to local hero Pat O’Connor, who’d started his yellow and black Ansted Rotary Kurtis on the outside pole.

Rathmann, O’Connor, Flaherty, and Tony Bettenhausen (Belanger Kurtis) swapped the lead back and forth during those opening 10 laps, but then veteran Paul Russo stormed past them all in the fan-favorite Novi. Using the supercharged Novi V8’s prodigious power, Russo then drove off into the distance, turning the race’s fastest lap and holding the top spot for another 10 laps before a right rear tire failure sent the big red car spinning hard into the wall in the Southwest Turn. The impact sparked a bright magnesium oxidation flash as wheel smashed into concrete, but Russo scrambled out unhurt and would later rejoin as a relief driver in another car.

Following the caution period for the clean-up, O’Connor took over once again, but Flaherty, driving the Watson in almost dirt-track style with its inside front wheel often lifting off the track in the turns, was beginning to find his pace. The two Pats traded the lead back and forth until Johnnie Parsons took over in J.C. Agajanian’s famous number 98 during the first round of scheduled pit stops. The 1950 Indy winner led for 16 laps before giving way to Don Freeland in the Bob Estes Phillips-Offy, but Flaherty reclaimed the top spot on lap 75, and that was it for everyone else. The Zink machine made its next stop without losing the lead, and stayed out front the rest of the way, rolling under the checkered flag just over 20 seconds ahead of Sam Hanks in the Jones and Maley Kurtis.

The fabled Luck o’ the Irish was certainly smiling on the man with the shamrock on his helmet that day, for not only had he avoided the carnage on the track, but no sooner had he completed his 200th lap than the Watson’s throttle linkage fell apart and he found himself idling toward Victory Lane. After getting the traditional winner’s kiss from Hollywood star Virginia Mayo, Flaherty told the crowd gathered around him: “I was lucky, and my luck held right to the end—well, just about. I had just taken the flag when the engine went back to idle. I pushed on the gas but nothing happened.”

“The throttle linkage broke off on the cool down lap, right after he crossed the finish line,” remembers Watson. “I didn’t think he was ever going to come in.”

A huge grin split his grime-covered face as the bare-armed Flaherty reveled in the glow of victory, the last man to win Indy in slacks and a T-shirt rather than flame-resistant coveralls. Despite his new records in qualifying—146.056 mph for one lap and 145.590 for four, nearly five mph faster than before—Flaherty’s 128.490 mph average for the 500 miles didn’t threaten Bill Vukovich’s two-year-old mark of 130.840 because of the day’s record 11 yellow flags. At the victory banquet he collected a check for $98,819 from the total purse of $281,922, and had he led a handful of laps more than the 127 he did, his could have been Indy’s first six-figure payout.

Chasing the Championship

Photo: IMS Photo

A week and a half later at Milwaukee Flaherty qualified only 11th, but after Watson reworked the car’s setup between qualifying and the race, he quickly began working his way to the front. Leading the last 43 laps of the 100-mile Rex Mays Memorial, he scored his second straight win to extend his lead in the National Championship.

Although he learned to race on dirt tracks, Flaherty was somehow regarded more as a pavement specialist, but a week after Milwaukee he won a 20-lap USAC Sprint Car feature on the half-mile dirt oval at Williams Grove, Pennsylvania. The next weekend he tackled treacherous Langhorne in Zink’s Watson dirt car, qualifying fourth and running with the leaders until bouncing off the fence when his right front tire blew on the 62nd lap.

Back in the roadster for an Independence Day 200-miler at Darlington, South Carolina, he finished 5th, a placing duplicated 10 days later on the red dirt of Atlanta’s Lakewood Speedway. Those latter points were fortuitous, though, because Pat had failed to qualify on the race’s original date. Only when rain postponed the proceedings for a week, and contractual conflicts kept several of the others from returning for the rain date, was he allowed to take the rescheduled start.

He also found time to win a pair of USAC stock car races—at Santa Fe Speedway in suburban Chicago and Saugus, California—as his fortunes continued to rise. As the height of summer hit the Midwest in mid-August, he went into the Indycar season’s sixth round on the Illinois State Fairgrounds Mile in Springfield leading the point standings 1500-900 over Don Freeland. Then it all went wrong.

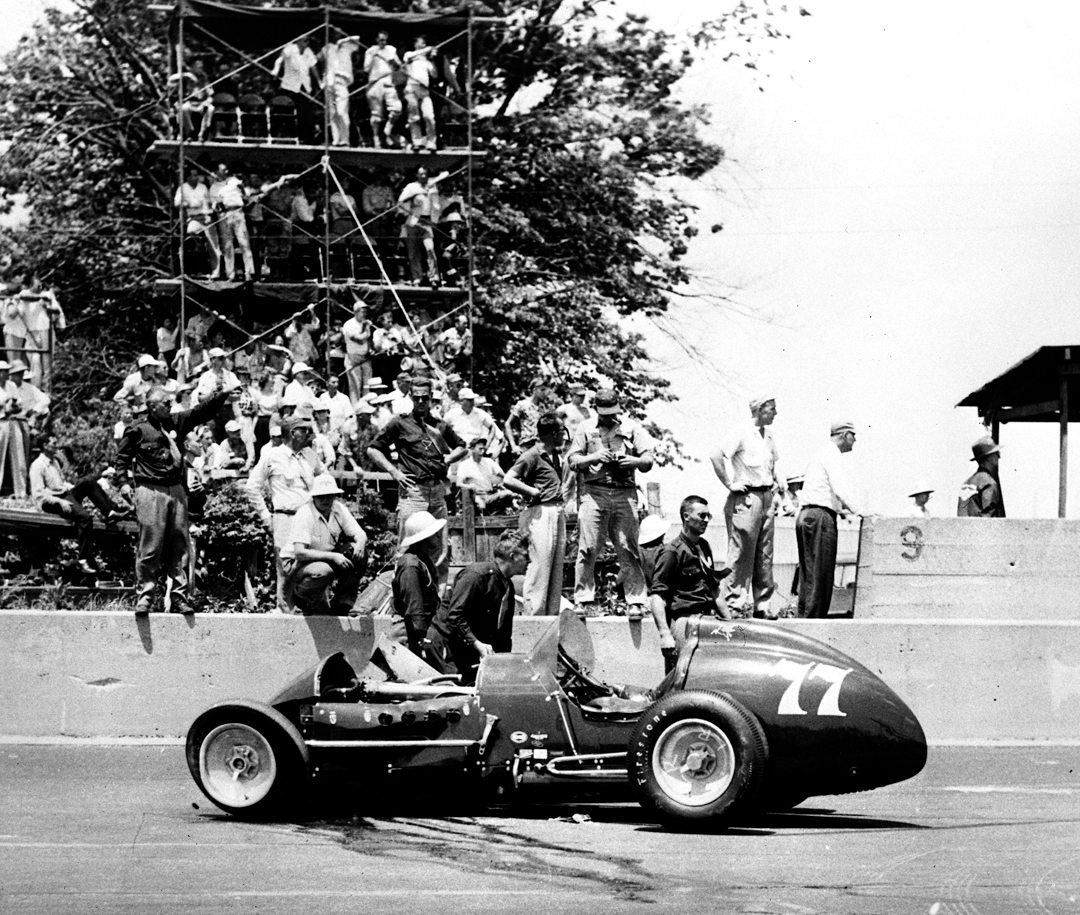

At the end of the back straight on the 27th lap, rookie Jack Turner spun in the “marbles,” and while most of the cars behind slipped safely past on the bottom, Flaherty chose to go by high, trying to squeeze between Turner and the fence. Turner’s car was still rolling backward up the track, however, and Flaherty’s pink Watson upright catapulted off its left rear wheel, flipped and landed upside down. Turner climbed out and ran over to try to tip the car back onto its wheels, but it was just too heavy.

Photo: Malloy Foundation Collection

Pat’s right arm and shoulder were crushed beneath the roll bar—his was one of the few cars in the race to have one—and he also suffered a broken jaw and other facial injuries as he instantly went from championship contender to convalescent care. The accident was eerily similar to the sprint car crash at Cedar Rapids, Iowa, that had sidelined Troy Ruttman for a year and a half just three months after he’d won at Indy in 1952. Ironically, Ruttman had been Flaherty’s teammate at Indy in ’56, driving Zink’s ’55 winner.

So severe was the damage to Flaherty’s arm and shoulder that recovery took two full years. After missing the rest of ’56—as his championship advantage eroded and ultimately swung in Jimmy Bryan’s favor—and all of ’57, he tried to return for Indy in May of 1958, but could not pass the track’s physical exam. He finally made his much-anticipated return to racing in a 200-mile USAC Stock Car race at Milwaukee that August, adding a Hollywood twist to his story by driving Tom Pistone’s Chevrolet to victory, leading 124 of the 200 laps.

During his absence, the Zink ride had been taken over by a string of drivers that included Jimmy Reece, Jud Larson, Ed Elisian, Jim Rathmann, and Tony Bettenhausen, so Pat hooked up once again with Harry Dunn to resume his Indycar career. His only Indycar start of the year came in the State Fair 200-miler at Milwaukee, three days after his triumphant stock car return, but he qualified the Dunn machine only 20th and finished 16th.

Back to Zink’s

Flaherty returned to the Zink stable for ’59, but Watson was no longer there. He’d left at the end of the previous season because Zink didn’t want him building cars for other teams. He went to work for Bob Wilke’s Leader Card operation where he and Rodger Ward created the famous Flying Ws dynasty that ruled the next several years. Driving cars now wrenched by Denny Moore, Flaherty started the season at Daytona, USAC’s single

Photo: IMS Photo

ill-fated visit to the dauntingly high-banked 2.5-mile Florida tri-oval. He finished 9th in the first of two 100-milers, but then managed only four laps before retiring from the accident-shortened second contest and was classified 14th. Next came Trenton, N.J., a second pre-Indy outing where he qualified 9th but dropped out of the rain-shortened race while it was still dry.

At Indy he started 18th in Zink’s Watson roadster—the same car Reece had put on the front row the year before—teamed with Bob Veith in a Moore-built example. Looking very much like the driver he was before his accident, Pat immediately surged to the front and before quarter distance began dueling with his pal Rathmann for the lead. He managed to lead a total of 11 laps, but with less than 100 miles to go crashed again while holding 4th, conceivably due to fatigue on another very hot day. So good had he run prior to that that there was even some talk of his crew having clocked him at under one minute for a lap, which would have broken Indy’s 150-mph “barrier,” but this was never officially confirmed.

The next week he went back to Milwaukee in Zink’s Moore roadster and qualified a fine 7th, but retired after 59 laps when the front suspension broke. That was pretty much the last hurrah for Flaherty in Indycars, although he did make one more start in June’s 100-miler at Milwaukee in 1963. There he drove a rear-engined homebuilt, the Peterson-Chevrolet, but made only 16 laps before the car failed.

Over the course of 14 years, but only eight seasons, Flaherty made 19 Indycar starts, bagging three wins, three further top-five finishes and two other top-tens. In the years ahead, some drivers would equal and surpass those numbers in a single season!

Pat finished out his car racing days in USAC’s stock car division, where he’d won twice from 16 starts prior to his accident. Following his comeback win at Milwaukee, he made two further stock car starts in each of ’61 and ’62, but then called it quits and returned to his day job as a tavern keeper.

Life After Driving

He drifted away from motorsports completely over time, and for 20 years afterward continued his winning tradition in the ancient sport of racing pigeons.

Bob Miller, who served for 17 years as the president of Chicago’s North Side Club for pigeon racing, was a close friend of Flaherty’s during that time and remembers him well. “He was the best. He’s a legend in Chicago as far as the pigeon flying is concerned. He’s the best flyer we ever had in Chicago.

“Pat started with the pigeons in California when he was a kid,” Miller continued, “then when he came to the Midwest, to Chicago, he flew with a Belgian guy over here, Freddie DeWeis. That was in the ’50s, and they just flew mediocre at that time. Then Pat was tied up with his car racing, and didn’t do pigeons for years and years; but he had race horses, harness horses. He was a very competitive guy; and really a good guy, too. After he almost got killed, he didn’t race (cars) too much.

“Pat was just the best. He could take a bird in his hand and tell ya, ‘today we gotta go for the training 20 miles,’ or ‘today they gotta go 80 miles.’ Just by handling those birds, he knew how far to train them every day. He was just the best, and a helluva good guy, too.”

Later on, Miller said, Flaherty would receive requests from car racing fans to sign memorabilia, and Miller would handle all the arrangements for sessions at the Belmont Feed store that served as unofficial pigeon racing HQ on Chicago’s North Side. “He never turned down any request,” Miller concludes.

Despite competing in one of motor sport’s most lethal eras—his own sheet time bearing violent witness—Pat Flaherty died at home, in bed, in California, succumbing to complications from emphysema in 2002. Even though he may have had other interests outside of motor sports, he will always be remembered as the man with the shamrock on his helmet who won the Indy 500.