Personally, I have driven some really good machines. I had a 917 Porsche that I thought was a truly remarkable car, and a 962, too. The only Indy car I had wished I had been able to race was the turbine car, because it was so dominant when it ran. The Ford GT40 was another great car I would have liked to have raced in period; I guess I was born just 10 to 15 years too late—I would really have loved to have driven and raced in the 1960s.

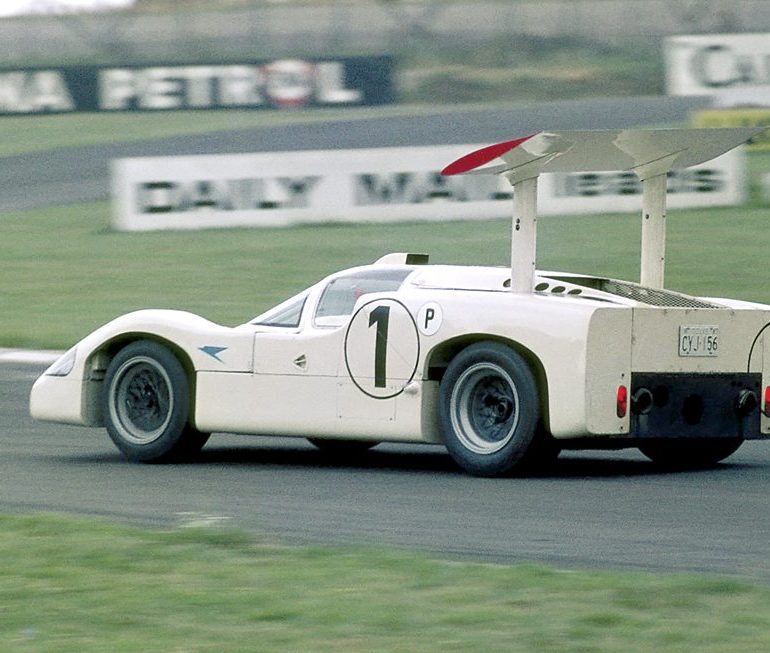

It’s hard to say what the greatest racecar is; each generation, era, and formula of motor racing has its own iconic car. For me, however, I’d have to say that the most trend-setting and truly great racecar was the Chaparral 2. If you look at the design, it predated composite chassis by 30 years, it used a wing as an aerodynamic device for greater stability and traction, and an automatic transmission. All these things are commonplace now, but Jim Hall was a pioneer in this field, a great engineer. He was definitely at the forefront of racecar technology, design, and application. He was curious, too, always looking to see where he could find an “edge”—a very smart guy.

One of my experiences at the sharp end of technology was as team manager of the Jaguar Formula One team. Unfortunately, Ford became a little restless and I left the project just when I thought we were making good progress. I have certainly had letters from many people since my departure, expressing the same view. Patience was a virtue that neither the Ford Motor Company nor the Premier Automotive Group had at the time. The fellow who brought me into the team had to go back to the states, and I felt a little as though I was left by myself and isolated. The worst thing was—there’s an expression I used—to bring the right people in, we had to look for the “island in the storm;” instead, everyone looked at the storm, total chaos sometimes. You cannot attract the right people into a team if your focus is wrong in the first place.

Many people have questioned the decision to build a complete new car when the Stewart F1 car was already a Grand Prix winner. However, you have to look at that European GP win in Germany and realize that the bulk of the opposition had retired. Three cars had collided with each other on the first lap, a combination of mechanical breakdowns and spins due to the wet weather that left just seven cars on the lead lap at the flag. The two Stewarts of Herbert and Barrichello just happened to finish in podium places. The car flattered to deceive, in my opinion. I’m not wishing to take away anything of that success, but it was a fortuitous win; it wasn’t that they were constantly up with the leaders on a regular basis. I definitely think there was an assumption that the car was further along the line than it actually was.

My biggest problem was the choice of drivers. Eddie Irvine might have been a good fast driver, but he wasn’t a team leader, or in fact a leader at all. He was a very destructive element in my view, and that really hurt. We needed someone who could lead the charge and motivate other people; the lead driver is a very important element in all that; the team manager, whoever he is, couldn’t do it himself. In the end, there was so much controversy and politics it was almost self-destructive. Then they brought the “Tornado,” Niki Lauda in, and all hell broke loose. It was a shame; I think we were further along the line than people gave us credit for. But when you have a budget, if you can call $200 million a budget, some people run out of patience in a short space of time.

On reflection, my regret is that I wasn’t able to achieve what we set out to achieve. As I look back, there were good days and bad days. I tend to remember the good days. There were a lot of great people at Jaguar Formula One, particularly the workers who tried very hard to bring us up. It was very gratifying to be a part of that.

As told to Mike Jiggle