Moss at His Best

When it was announced in 1958 that the capacity limit for Formula One would change from 2.5 liters to 1.5 liters for the 1961 season, many constructors thought the changes would never be implemented and that the “lack of power” from smaller engines would not be popular. The British constructors particularly stuck their heads in the sand and thought the problem would go away. They even went so far as to support an alternative Intercontinental Formula for larger engines.

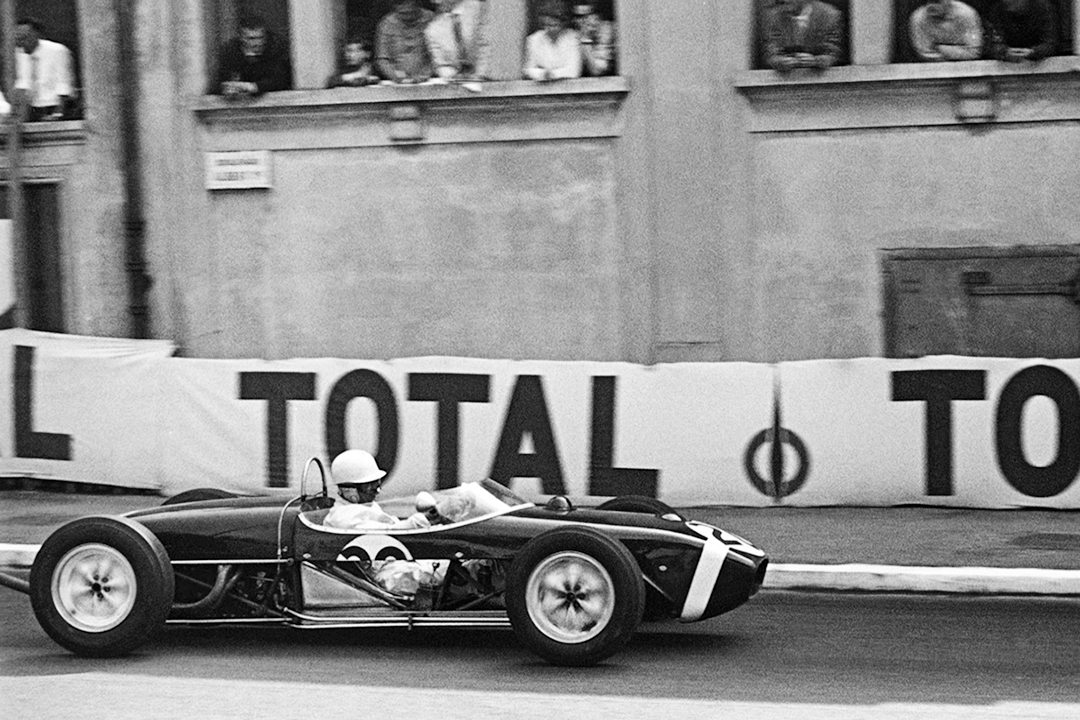

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Ferrari and Porsche, however, were actively involved in Formula 2 and had 1.5-liter engines that they could adapt and develop for the new Grand Prix formula. Much of 1960 was spent, especially by Ferrari, in trying the smaller engine in the then-current F1 chassis, followed by development of an all-new, rear-engine car. This car showed up at Monaco in 1960 with the 2.5-Dino engine and was very impressive. Throughout the season, it was improved in a number of F2 races. It had, of course, been a huge move by Ferrari to go to a rear- or centrally mounted engine. In spite of Cooper’s success with their cars in the 1959–60 Grand Prix season, even they were not ready to compete when both the new Ferrari and Porsche appeared in 1961.

“The Old Days”

Formula One, in the early 1960s, would not be recognized by teams and fans today. In 1961, there were seven Formula One races on the calendar before the first championship race at Monaco took place on May 14. The first two were essentially English races: the Lombank Trophy at Snetterton won by Jack Brabham’s Cooper T-53 and the Glover Trophy at Goodwood that went to another Cooper T-53 driven by John Surtees. The next two races were much more international. The Grand Prix de Pau went to Jim Clark’s Lotus 18, which was a 1960 car, as were all the cars in the race except the two new Emerysons which were not at all competitive. A good field appeared for the Grand Prix de Bruxelles at the Heysel street circuit. This was a race run in three heats, with two 1959 Porsches being brought for Dan Gurney and Jo Bonnier. They surprised everyone by getting on the front row of the grid for the first heat. Bonnier won the heat, but Brabham’s Cooper won the other two heats and finished 1st overall. The subsequent Vienna Grand Prix had a small field and saw Stirling Moss win in a Lotus 18.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Brabham and Bruce McLaren, both in Coopers, then won the Aintree 200 in Britain. On the basis of the first six nonchampionship races, the future looked good for Cooper and Jack Brabham for another championship. Then came the seventh nonchampionship event and suddenly everything changed. The Gran Premio di Siracusa was a popular race, even though it was only three days after the Aintree 200. New, 1961 cars appeared for Brabham, a BRM for Brooks and Graham Hill, and the Emerysons, while Moss had the Rob Walker Lotus 18 and Clark the works car. Then there was an entry from FISA, not the rule-making body for motor sport, but the Federazione Italiana Scuderie Automobilistiche. FISA was a grouping of small Italian racecar builders. Their entry was the brand-new Ferrari 156—the “sharknose”—and it was entered for the young and little known Formula Junior driver, Giancarlo Baghetti. However, it was being looked after by Ferrari mechanics. While Dan Gurney got the four-cylinder Porsche on pole, Baghetti was next ahead of Surtees in a Cooper. Baghetti had a good fight with Gurney who couldn’t keep the Porsche ahead of the new Ferrari, resulting in Baghetti winning by five seconds—and there weren’t even any works Ferrari drivers there!

XIX Monaco Grand Prix

The 1961 Monaco Grand Prix has often been described as one of the great Grands Prix, and for Ferrari, it was outstanding with superb performances from both the new 65- and 120-degree engines. But it was spoiled for Ferrari by the supreme show put on by Stirling Moss.

At the last minute, Ferrari team manager Tavoni and engineer Carlo Chiti were worried about the 120-degree engine and so decided to bring test driver Richie Ginther into the team to join team leaders Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips. Ginther would run the 120-degree unit, which was thought to be potentially less reliable. Bonnier and Gurney in Porsches were expected to be the opposition, with good braking expected to pay off at Monaco. Porsche had kept drum brakes instead of introducing discs. The Porsches had surprised everyone at Siracusa, even though Baghetti was possibly braking early when under pressure from Gurney. At Monaco, Gurney was in an older car, while Bonnier and Hans Herrmann had new fuel-injected engines in newly designed Type 787 machines.

Tavoni was very proud of the new Ferraris, which received lots of attention in the glamorous setting of “old” Monaco, before it was ruined by huge modern buildings. But he knew the Ferraris would have to work hard in the principality. He thought this was the circuit least suited to the new Ferrari’s handling. Additionally, Ginther would have to qualify for one of the 16 places on the grid, while Hill and von Trips were guaranteed a start. These were the days when each circuit and organizing body made up the rules concerning how many entries were allowed and how disputes were settled. It was primitive by modern standards, and when the cars were weighed, each team had to declare how much fuel it was carrying so the officials could add that into the total weight of the car!

At Monaco, the racing world got its first close look at some of the new cars including the Ferraris, Porsches, and the new Lotus 21, which was to be driven by Jim Clark and Innes Ireland. The main obvious difference between the three new Ferraris was in the covering for the carburetors. The cars for Hill and von Trips had a gauze covering over a single, large opening in the rear bodywork, while Ginther’s car featured two separate openings because the carburetors were further apart in the 120-degree engine. This single gauze cover replaced the Perspex covers which had been seen in testing, though these would appear again from time to time.

The three Ferraris immediately set very fast practice times. Ginther’s pace indicated that he would qualify without difficulty and all three were in the 1 minute 41 seconds range, as was Moss, after sorting out some fuel feed problems. The speeds were, at first, affected by the fact that the drivers had to get used to some subtle changes to the circuit. The pits had been moved to the side of the narrow “island” opposite the position they occupied in later years. The Tobacconist Corner on the approach to the old pits had also been eased somewhat. Added to this was the fact that Armco barriers had sprung up in many locations for the first time.

Jim Clark and Innes Ireland began to get on the pace in the Lotus 21 and so did Graham Hill with the BRM, though this had a 4-cylinder Climax Mk.II engine—the V-8 was still a long way off. The Porsches were busy getting suspension settings right and then Clark went by on what looked like a pretty wild lap for him, with a time of 1 minute 39.6 seconds. He then disappeared into the new barriers, and the car, which had just been built, had to be rebuilt!

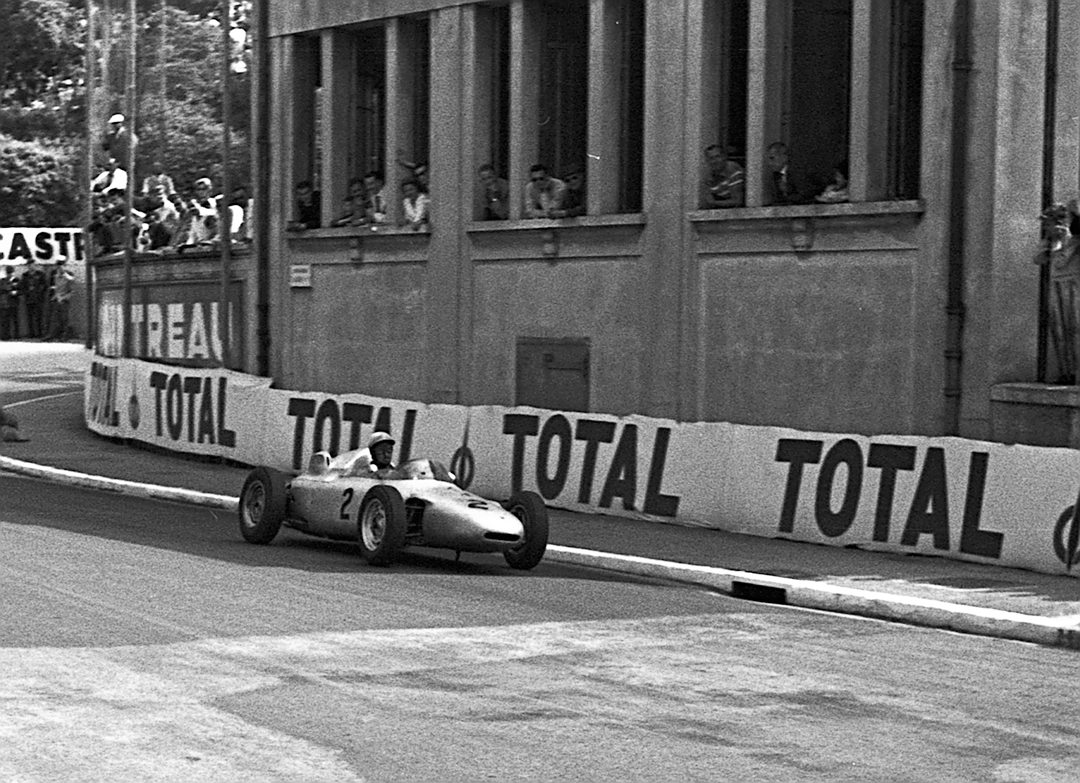

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Those of us who can remember getting up early for Monaco’s Friday practice might recall how odd it felt when the F1 cars went out at 7:15 a.m.—this after we had been watching Formula Juniors since 5:30 a.m.! If we had managed to sleep through the Juniors, it wasn’t possible when the 1.5-liter F1 cars emerged. First, Ginther came out for the first of many laps to familiarize himself with the new car, and to test its reliability. Then both Phil Hill and von Trips were quicker than the previous day without making any major changes. Ginther’s 1:39.6 made him quickest of all with Clark’s time 2nd. Graham Hill used the new Mk.II engine to good effect to split the Ferraris, but Phil Hill and von Trips looked happy enough in 4th and 5th. Jack Brabham was absent, as he had gone off to try and qualify for the Indianapolis 500. Stirling Moss was trying the spare Rob Walker car, the Cooper T-53, but this was not handling well and was put aside, so he returned to his trusty Lotus 18. The two Porsches weren’t going very well and the fitting of 4-speed gearboxes had not helped. The Ferraris put in more laps in the afternoon but didn’t go quicker.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

The final session was scheduled for Saturday; this would be the last chance for the nine “nonseeded” drivers to qualify for the four final grid positions. Ginther was immediately on the pace again, the only change to the Ferraris being the addition of a 6-volt battery in addition to the 12-volt. This was Chiti’s idea to raise the current to the coils at the higher rpm the Ferraris were using. This modification was retained for the season, and the engines were able to use 500 rpm more than expected, which got Phil Hill and von Trips into the 1:39 bracket. A lot of other drivers were going quickly on Saturday, with Graham Hill equaling Clark’s time.

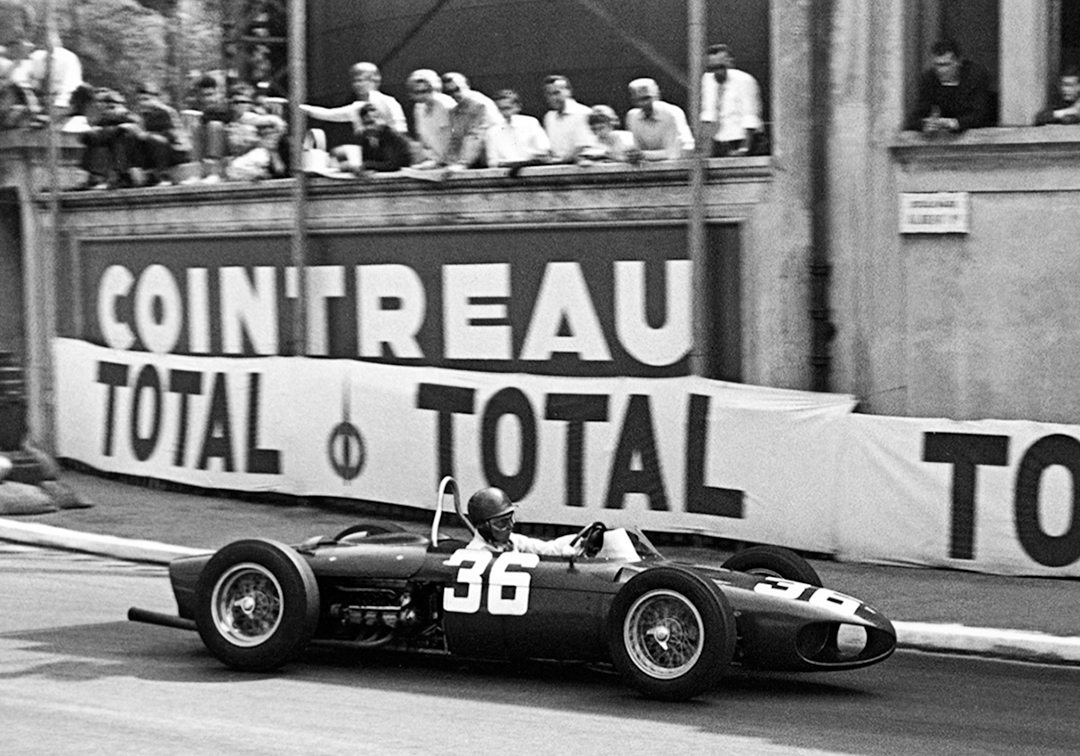

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Then, Moss got going very quickly and, after several laps, he put in a lap at 1 minute 39.1 seconds to take pole position. Shortly after this, Innes Ireland was having trouble selecting gears and got second instead of fourth and had a huge crash in the tunnel in front of Moss. Ireland was badly injured, and the car was totally destroyed. Moss stopped to see if Ireland was all right, and the delay meant that several drivers lost the chance of a quick lap, resulting in Henry Taylor and Masten Gregory not qualifying. However, Michael May got in due to some good slipstreaming. In the end, Moss was on pole from Ginther, Jim Clark, Graham Hill, Phil Hill, with Tony Brooks and his BRM-Climax ahead of McLaren’s Cooper-Climax and von Trips. Bonnier was next in front of Gurney in a slightly older Porsche. Brabham was at the back, not having returned from Indianapolis practice in time for the final session.

Race Day

As the flag came down for the start of the 100 laps of the Monaco Grand Prix, Richie Ginther rocketed away from his position in the middle of the front row and led into the first corner. At the end of the first lap, the 120-degree engine in Ginther’s car was pushing the little American away from the field. It took a good five laps for Moss to recover from this surprise and take up the chase. The order at the end of the first lap had been Ginther, Clark, Moss, Gurney, Brooks, Bonnier, Phil Hill, McLaren, Graham Hill, von Trips, Surtees, and then the flying Brabham who had only just arrived from the United States 45 minutes before the start!

In the first dozen laps, Ginther started to pull away, but he was taking Moss with him. Moss was now only 1.5 seconds behind by lap 10 with a surprisingly fast Bonnier on his tail, the Porsche now going faster than it had in practice. Moss’s car was running with the side body panels removed, seemingly because of the heat but really because mechanic Alf Francis had spotted a crack in the chassis and had welded it up, prior to the start.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

On lap 14, both Moss and Bonnier managed to slip past Ginther and, shortly afterwards, Phil Hill pushed his Ferrari past Dan Gurney. Then von Trips did the same thing putting the three Ferraris in line in 3rd, 4th, and 5th. From laps 20 to 24, the red cars fought among each other. Phil Hill sneaked past Ginther and all three Ferraris moved closer to Bonnier and the Porsche, as Moss pulled out a slight gap. For several laps, the Ferraris and the Porsche were within inches of each other, courting disaster, but somehow managing not to make contact. By lap 40, Ginther, who had been sitting behind von Trips for some time, forced his way past, caught up with Bonnier, and then made a heart-stopping move up the inside at the hairpin at the end of the lap. Ferrari and Porsche shot past the pits side by side, the Ferrari power showing as they approached Sainte Devote. Ginther was now getting his second wind as he set out again after teammate Phil Hill. As a result, Moss’s 10-second lead was no longer growing. Ginther, driving brilliantly, was pushing Hill and towing the Porsche along for good measure. By half distance, all the lead cars were circulating under their practice times and cutting Moss’s lead. A further five laps later, the Hill-Ginther pace brought the two Ferraris up into Moss’s mirrors. While Bonnier’s car expired on lap 60, one of the best ever Grand Prix races was unfolding with Moss’s underpowered Lotus fighting fiercely to stave off the more powerful Ferraris, which were flying on a circuit thought to be less than suitable to the character Baghetti had shown the car to have on the sweeping Siracusa road course.

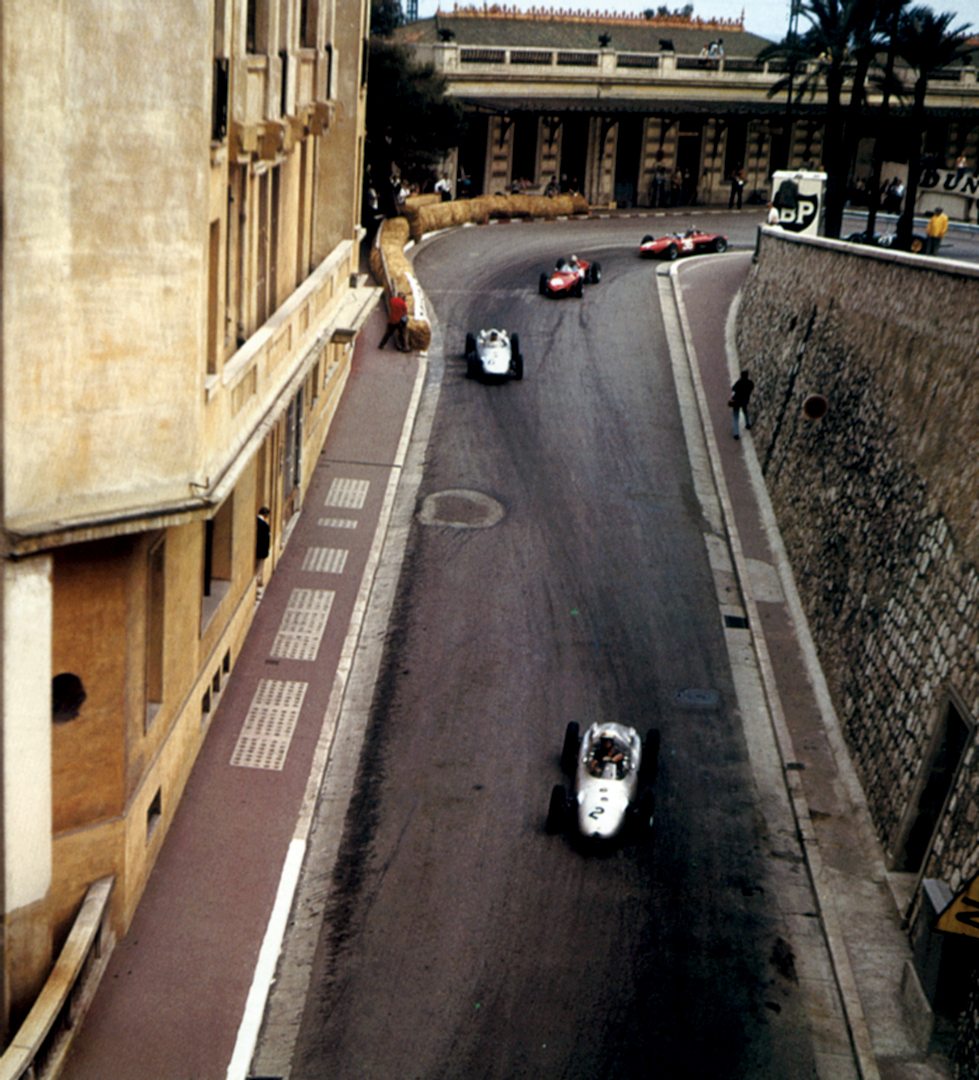

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Stirling Moss described how he approached the race, knowing the Ferraris were more powerful than his Lotus-Climax, “…the principle of it is that the race is really made by sustaining the maximum amount of speed for the maximum amount of time. It’s like saying ‘I’m going to run a hundred yards and keep it going for a mile.’ It just doesn’t happen, but there at Monaco it did. You can’t really compare that with the Mille Miglia or some other races, but at Monaco it was clearly closer to the limit than at any other race for more of the time. What counts is the amount of effort and the kind of effort you put in on any one day.”

While some reports of the day said that Ginther and Hill were not a match for Moss, in terms of passing slower cars, in fact, they kept finding the slower cars in just the wrong places and they lost more time than Moss, thus having to win that time back again. Considering Ginther’s limited Grand Prix experience, his driving looked highly impressive to all those gathered within a few feet of the cars, as they sped past. Phil Hill described the handling of his car during the race: “I was impressed by the difference in Richie’s car and our car. I mean Trips’s and mine. The road holding of Richie’s seemed to be considerably superior. To me, this wasn’t Richie, it was the car. There was no question that anyone who drove the higher CG [center of gravity] engine later in the season remarked upon it all year long. I don’t think it would make much difference, if any, on a fast circuit but certainly on the back and forth of a circuit like Monaco, the difference was very noticeable.”

On lap 75, Ginther got past Hill and set off after Moss with a new determination. Then, on lap 84, he set fastest lap of 1 minute 36.3 seconds, not that far off the record set the previous year in a 2.5-liter car! Ginther was now getting closer to Moss, with Phil Hill hanging on behind him. First Moss and then Ginther’s Ferrari lapped von Trips on lap 89, and Ginther, who had furiously been chewing gum the whole race, spat it out. He seemed to be getting even more serious! The Ferrari pit was nearly hysterical and, at every lap, there was a message to Ginther to go quicker, to catch Moss, to give everything—clearly he was doing all of that.

The race finally came to an end with Ginther 3 seconds behind Moss, while Hill had fallen further behind. Hill stopped on his slowing down lap to give von Trips a ride because car number 40 had an electrical failure, the first and only sign of Ferrari weakness. According to the Monaco rules, von Trips was classified 4th even though he was not running, rather than down the order, behind those who were still going. Even Jim Clark in the Lotus was still running after early mechanical problems had put him eleven laps behind.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Moss was eloquent in the way he summed up the Monaco race: “I have never, ever driven a race as hard as I did at Monaco, at least for a good 90 percent of it. I’m convinced of it. I’d go around a corner and, if it wasn’t quite right, I’d say to myself, ‘Well, let’s try to start the perfect lap from here,’ and then I’d go along and after eight corners, if it still wouldn’t be exactly right, I’d say, ‘OK, let’s start from here.’ All the time I was doing this to keep myself right on the limit. I had the Ferraris between 2 seconds and 4 seconds behind me after I had got past Richie, and that was nothing, because every time I went around a hairpin, I could see them, and all the time I was thinking they were just sitting there. So I thought, ‘Gee, let’s see if I can make a car’s length,’ and I’d make a car’s length, and then the next lap they would take it away, and I thought they were just playing with me. I guess Richie was doing the same thing. If I had done my pole time every lap, I would have only been 40 seconds quicker at the end than I was. Richie and I did the same lap time as it happens, and my whole race was only some 2 seconds quicker than his in the whole 100 laps, so he wasn’t hanging around. Phil was also in there for most of the time, and I knew that for most of the race.”

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Richie Ginther was quoted as saying that he could not have driven any harder, and the spectators were in agreement, as all the leading cars received a magnificent reception on the slowing-down lap. This had been a spectacular Grand Prix debut for the new Ferrari “sharknose,” but it hadn’t won. Ginther thought Monaco had been his greatest race, and the fact that both Moss and he had lapped 3 seconds under pole time was a sign of just how fast the race had been.

The Ferraris had had some problems with the carburetors flooding on the exit of tight corners, and Hill was experiencing some brake problems towards the end of the race. Hill was now optimistic about the rest of the year, but said he would have swapped some of the Ferrari’s power for the handling of Moss’s Rob Walker Lotus. Then and later, all the drivers and people, who had been at Monaco, acknowledged that they had seen Stirling Moss drive one of the best races of his career.

And in Moss’s view, “When the race was going on, I didn’t see it as ‘one of my best,’ because when you are racing, you are, usually, as fast as you reasonably can be at the time, and it’s only when you look back on it and put the whole thing together that you realize you were absolutely flat out.”