1960 Kieft Formula Junior

The history of British motorsport is rife with postwar racecar manufacturers that saw their genesis in the hands of a dedicated engineer or enthusiast. Names like Colin Chapman (Lotus), John Cooper (Cooper) and Eric Broadley (Lola) are just a few of such individuals that set out to build a personal toy and ended up creating a national industry. While many of these names are now hallowed, there are literally dozens of others that saw varying degrees of success but, for any number of reasons, haven’t attained the same level of notoriety. One such constructor was Cyril Kieft.

The Cars of Cyril Kieft

Cyril Kieft was born in Swansea, England, in 1911. His father was in the steel industry, and so by 1939, young Cyril had worked his way up to managing the family steel works at Scunthorpe. During his work at Scunthorpe, Kieft began attending race meetings at Donington, as a spectator.

After World War II, Kieft read the handwriting on the wall, and fearing the eventual nationalization of the British steel industry, left the family steel works to form his own tool company, Cyril Kieft and Co., at Bridgend, in South Wales. It was not long thereafter that Kieft began to get involved with the local Tenby Motor Club, which held a hillclimb at Lydstep. Yearning to get behind the wheel himself, he soon took the plunge and purchased a 500-cc Marwyn to compete at Lydstep, but quickly became disillusioned with the car’s performance. After witnessing fellow competitor Jack Moor roll his WASP, Kieft promised his wife that he would retire from racing—or at least, from driving.

Kieft’s disappointment in his Marwyn may not have been unfounded, as by 1949, Marwyn went out of business. Thinking he could do better, Kieft purchased the company’s remaining assets and set about building his own car. The Kieft MkI was, by and large, a further development of the Marwyn, with the exception of a

completely revised wishbone suspension system utilizing Metalastic bushings, in tension, as dampeners. While the car was completed in only seven months, it suffered from inherent stability problems and so wasn’t particularly competitive. However, Kieft’s keen business sense grabbed on to the idea of tackling the 350-cc and 500-cc international speed records with the car, as a way of gaining some notoriety. With John Neill, Ken Gregory and an up-and-coming, young, 500-cc racer by the name of Stirling Moss at the wheel, the Kieft MkI went to Montlhéry, in France, in November of 1950, and returned home with 13 international speed records.

As a result of this fantastic result, Kieft offered young Moss a seat on his F3 team for the 1951 season. But Moss felt that the MkI wasn’t going to be competitive against the 500-cc machines being made by Cooper. Instead, Moss suggested that Kieft fund the construction of a new racer designed by former BRM design engineer John A. Cooper (no relation to the Cooper Car Company) and Ray Martin to Moss’s specifications. The offshoot of this was a new company, Kieft Car Construction Ltd., which would sell customer versions of the prototype that Moss would race in 1951. This new company, based in Wolverhampton, would include Kieft, Dean Delamont, Martin, Moss, Cooper and Moss’s manager Ken Gregory, as directors.

This new car, the Kieft CK51, was unusual in a number of respects, perhaps most notably for its far forward driving position and adjustable suspension that incorporated a rear swing axle with rubber springing modulated by a complicated pulley and cable system. After delays in getting the car completed, it made its racing debut at Goodwood on May 14, 1951. Though the car had some teething problems in qualifying, Moss and the prototype decimated the field in the race, winning by over 27 seconds! According to Moss, “Of all the cars I have ever driven, that Kieft was the greatest step forward I have ever experienced—miles ahead of its class.” Moss went on to notch up numerous victories in the CK51 prototype throughout the 1951 season, but after the car was destroyed in the 1952 Brussels GP, Moss found that the later production models lacked the same competitiveness, resulting in Moss resigning his directorship and returning to racing Coopers.

Kieft continued in Formula 3 competition with Don Parker, who was perhaps the best known and most successful driver of the formula, winning many races including the Autosport 500-cc championship in 1952–’53 with his heavily modified Kieft.

During the 1954 season, Kieft concentrated on development of a lighter weight 1,100-cc sports racing car. The Kieft Sports became the first car to race the new Coventry Climax FWA (firepump) engine. It was mated to an MG gearbox and employed a one-piece fiberglass body—a first in the industry. This car was intended to be at home both on and off the track but enjoyed little success. Notably, this model competed at Le Mans driven by Rippon and Black where it ran well until an axle failure near the halfway mark.

In 1955, Kieft granted Berwyn Baxter, a successful club racer, use of the Kieft name for works entries. Cyril had by now lost interest and, having expended considerable sums of money in racing, turned his attention to his other business interests. Berwyn raced one of the 1100 Sports fitted with a Turner 1500 in club events and at Le Mans in 1955 co-driving with John Deeley. However, they retired on lap six with overheating. Berwyn shelved the troublesome Turner but nothing came of his further efforts with the car, despite some potential to market a production version. Kieft Sports Car Co., Ltd. continued on with preparation of Berwyn Baxter’s own and customer competition cars.

Enter the Junior

Realizing that Italy needed an inexpensive platform to popularize the competition of true single-seaters, and as an inexpensive stepping stone for young drivers, Count Giovani “Johnny” Lurani first proposed the concept of Formula Junior to the Italian Sports Commission on November 30, 1956 and again to the Commission Sportive International in January 1958. This new class, founded around the use of small displacement powertrains derived from production cars, met with instant success and drew a large number of small but well-known Italian manufacturers. Stanguellini, Taraschi, Volpini, and Bandini were just some of the early better-known marques to embrace the Formula Junior concept. By 1959, Formula Junior’s popularity led to it being elevated to an internationally recognized FIA class. From that point on, Formula Junior evolved rapidly.

The entry of English designs in 1959 had a profound effect on the level of competition and quickly relegated the early Italian designs to the back of the grid. In 1959, Lotus introduced its first midengine racecar in the form of the Lotus 18 Formula Junior, and from that point forward only a midengine car would be competitive. British manufacturers like Cooper, Lola and Lotus supported full works or quasi-works teams and, as a result, many future F1 stars gained valuable seat time racing these nimble, small-displacement cars. Peter Arundle, Denis Hulme, John Surtees, Jim Clark, Jackie Stewart, David Hobbs and Mike Spence, just to name a few, honed their skills in Formula Junior.

New Owners, New Car

Lionel Mayman and his brother-in-law John Turvey were a couple of successful club racers who owned an aftermarket tuning business specializing in Triumph Herald engines, marketed under the name “Kieft Power.” Shortly after the announcement of the proposed FIA Formula Junior regulations for 1959, Ron Timmins, the mechanic who had developed Lionel’s successful aluminum-bodied Morgan +4 racer, presented a plan to construct a Formula Junior, based around the firm’s tuned Herald engine, that Mayman could race in the new formula.

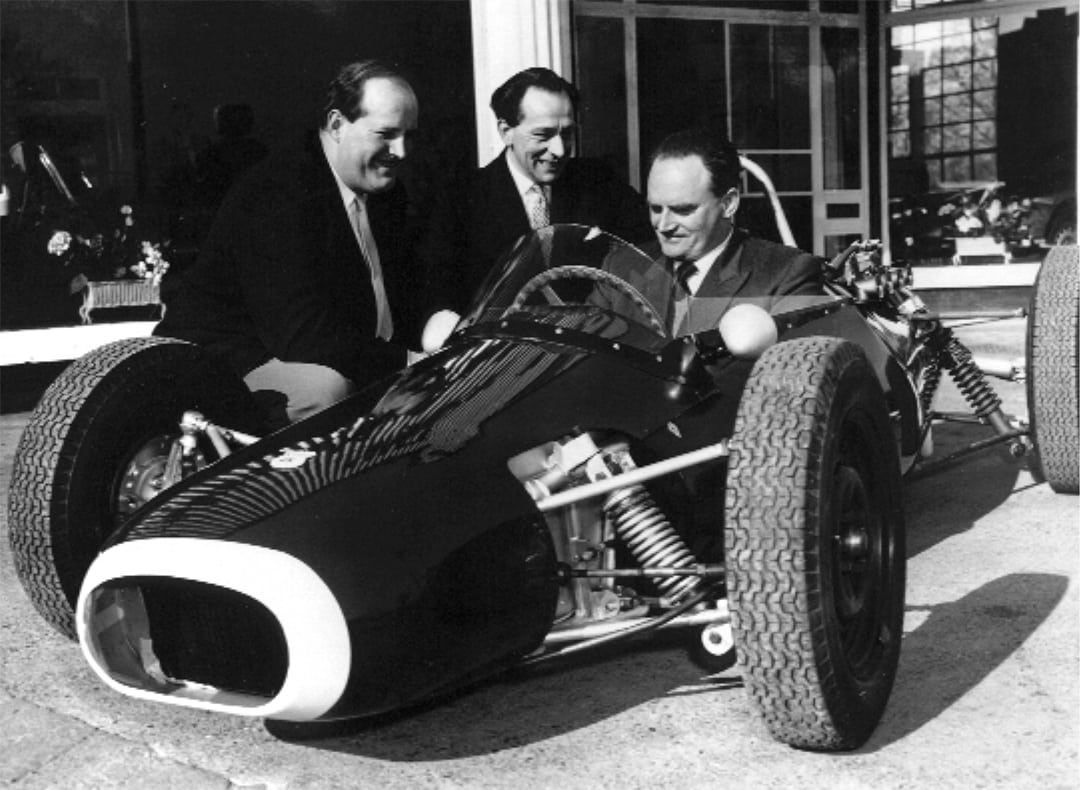

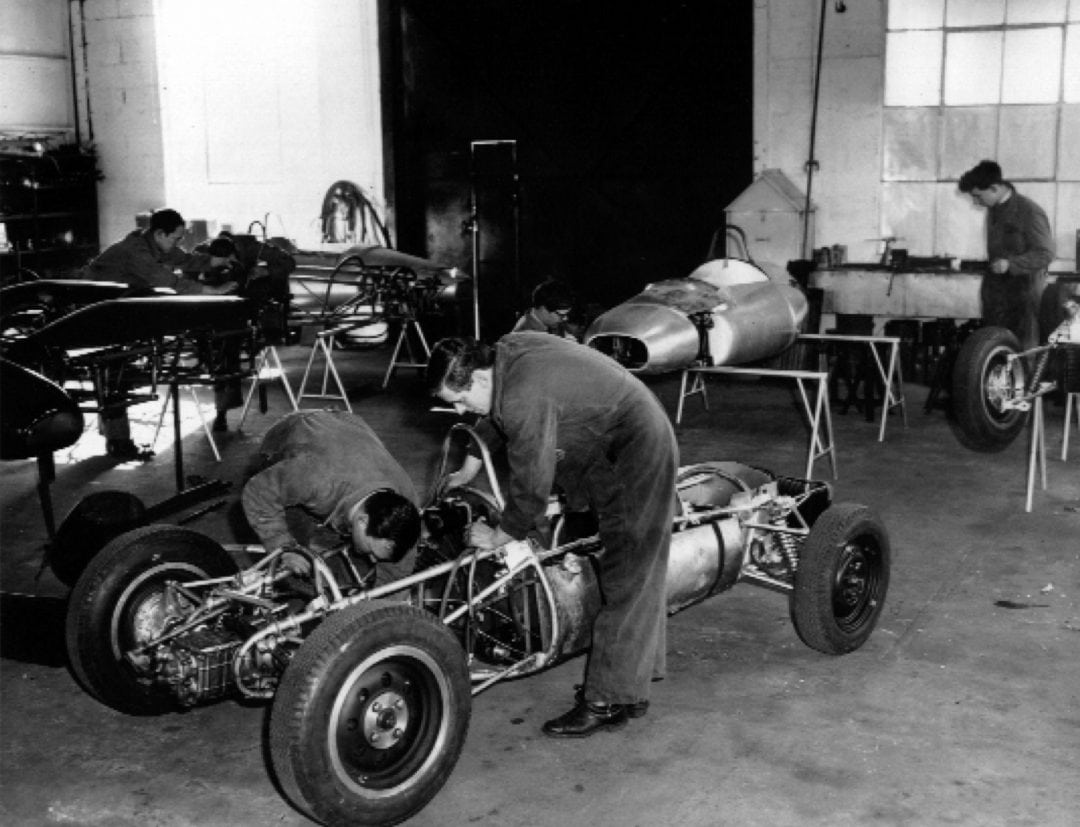

The Junior that Timmins constructed looked so promising that it was decided the car should go into production. As a result, an ambitious plan was hatched in the spring of 1960, whereby Mayman and Turvey purchased the remains of the Kieft Sports Car Company and the full rights to use the Kieft name. The directors of this yet-again resurrected Kieft were Mayman, Turvey and Mayman’s wife Pauline, who drove for the BMC rally team. Ron Timmins was appointed designer and chief engineer, while Dutchman Win Winklehof served as draftsman. With the addition of more mechanics and personnel, space rapidly dwindled so the company and its bits and pieces were moved to Drakes Cross, 10 miles south of Birmingham.

The Kieft Formula Junior followed conventional practice and in many ways appeared to borrow from the Cooper F1 designs of the time, with curved upper, main-frame rails and bulkheads. The frame was constructed of 1.5-inch, 17-gauge, as well as 1.0-inch and .75-inch, 16-gauge seamless steel tube, held together with bronze welding. The front suspension employed a conventional double wishbone design, while the rear featured reversed, lower wishbones supported by a single radius rod. Other unique suspension features included adjustment for ride height at the top of the shock mounts, both front and rear. Rounding out the package, Kieft fabricated their own rear uprights from sheet steel and had wheels specially cast in Elektron magnesium by Birmid.

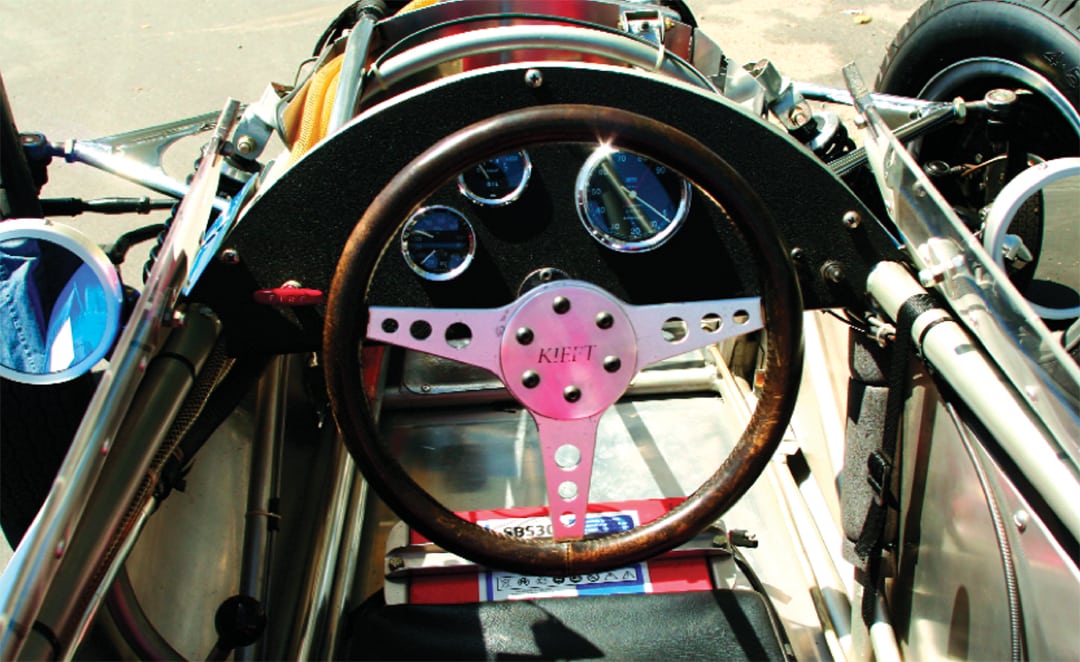

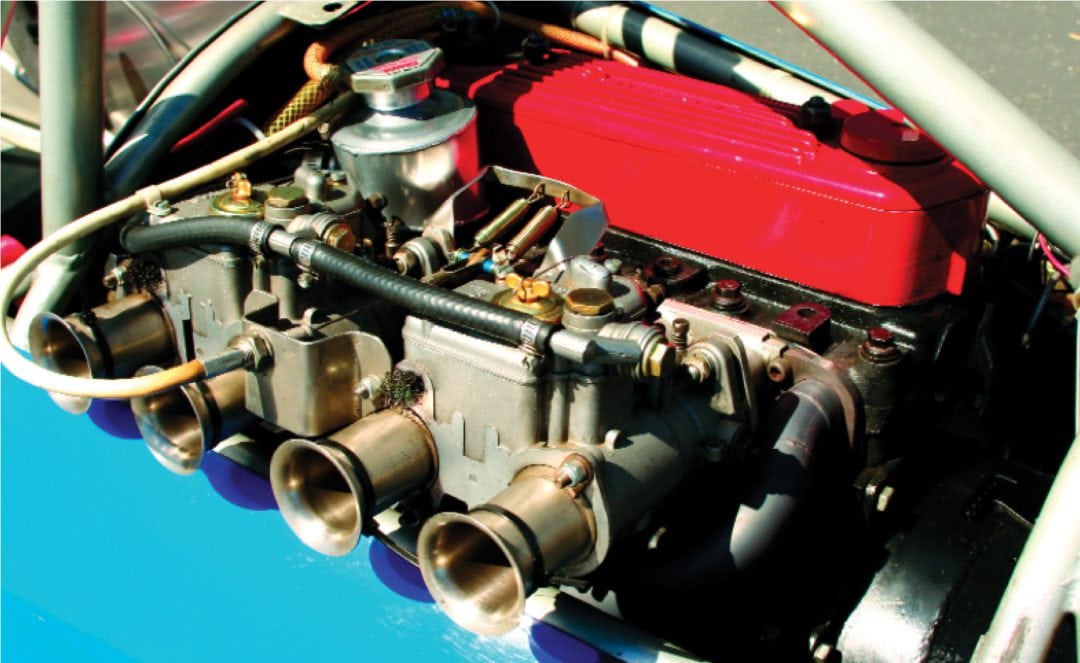

The Kieft was likely the shortest of all Formula Junior cars, at just 10-feet long, with a 6’11” wheelbase, and was noted for its low, 2.5-inch ground clearance. The production bodies were constructed of aluminum in four sections. While the prototype had a slightly different look, some detail differences and a “hotted-up” Triumph Herald engine, the production cars were equipped with Arden-prepared Ford 105E engines. In an effort to further lower the car’s center of gravity, the engine was laid over at a 15-degree angle. Interestingly, a Lloyd Roach oil-to-water heat exchanger was located longitudinally just in front of the engine and, initially, twin oil-temperature gauges monitored oil both in and out of this device, though this setup would prove problematic. In the gearbox department, the Kieft was originally supplied with a Renault Dauphine 4-speed, though an Arden-modified 5-speed was advertised as available.

On March 17, 1961, the works brought two production Kieft Juniors to Silverstone for a press introduction, a 4-speed and a 5-speed version for driver Peter Arundel to demonstrate. The cars were fitted with Ford 105E engines tuned by Jim Whitehouse of Arden Racing and Sports Cars, Ltd. These engines were reported to be 82 hp “cooking” engines, with the “works” engines expecting substantially more. While these early examples utilized wet sump lubrication, Kieft was in the process of switching over to dry sump units later in the season. The press reported the car to be easy to drive and nearly neutral with good performance and no fade from the 9-inch, double-leading shoe, Girling drum brakes. “It could pull 8,000 rpm on the straight before easing off for Woodcote,” according to one press report. When Arundel drove the 5-speed car, he reportedly “told Kiefts that they should be quite content.” After a requested spring rate reduction on the front, Arundel managed to lap within .6 seconds of the official Formula Junior lap record, which he held in a Lotus 20. Not a bad showing with a detuned “cooking” engine!

According to Mayman, there were five cars completed plus the prototype, which was probably cannibalized for parts. They were all painted deep blue, except the last car, which was painted green. The works cars were driven at various times by Lionel Mayman, John Rhodes, Chris Summers, and T. Dickson. Two of the cars were originally sold to privateers W. Vanglton and David Prophet.

The prototype Kieft (with Herald power) appears to have been entered to race as early as April 2, 1960, at the Oulton Park Spring Meeting for John Turvey but may not have actually raced. Race reports indicate that the first customer car appeared on December 26, 1960, at the BRSCC Boxing Day event at Brands Hatch. This car was driven by David Prophet, finishing 6th in a field of 14. Curiously, this car was BMC-powered. Prophet went on to race his Kieft many more times but transitioned to Ford power between June and July of 1961. For the March 25, 1961, Snetterton M.R.C. International Lombank Trophy, entries were listed for four Kiefts—Sommers, Dickson and “tbn” in works cars and David Prophet as a privateer. Records are sketchy, but according to Mayman, “the cars had numerous placings and an occasional win.” John Rhodes, in one of the works cars, scored a win at Mallory Park on July 2, 1961. Mayman himself scored a fine 5th place at Silverstone on June 24, 1961.

The Kieft Juniors continued to compete into 1963, primarily in small club events, but were by then far outmoded, compared to cars like the monocoque-based Lotus 27. Often hailed as “the car of the month club,” Formula Junior technology progressed at such a prodigious rate that small manufacturers like Kieft, and numerous “homebuilders,” were simply left behind. According to Mayman, the cash requirements necessary to try and keep up with the likes of Lotus, Cooper and Brabham were having such a negative effect on the business that the directors decided to halt Junior production in 1962, bringing an end to the saga of the Kieft name in motorsport. In the end, components for about six more Juniors were sold along with various bits, meaning that in total about 15 frames were produced. Though absent from racing, the Kieft name continued in the automotive business, under the control of John Turvey, as a Roots Group car dealer for many years.

Chassis #2

Marc and Marilynn Nichols acquired Kieft Chassis #2 in 1988. Prior to that it had been campaigned in British historic racing by Fred Edwards. A letter furnished with the car was from Steve Griffin, a former Kieft works mechanic who had provided Edwards with an original nose badge. Griffin was excited to hear of the sale to Nichols and was instrumental in providing valuable information and original photos of the works and cars. He also was able to put Nichols in contact with Kieft director, Lionel Mayman. Mayman provided Nichols access to his personal scrapbook and valuable insight into Kieft’s activities, which were invaluable in Nichols’s restoration of chassis #2.

Nichols first raced the car shortly after purchasing it but quickly discovered that the car had problems. Though the car was complete and original, it was war weary. A full restoration was in order and four years were spent on a total frame-up rebuild. The chassis and body restoration were looked after by Prince Race Car Engineering and The Carriage & Motorworks, while PHP Race Engines rebuilt the Ford 105E engine. The aluminum body parts were original. However, the tail cone had to be re-created from photographs as it was long gone due to a rear suspension modification, done in period (possibly by Kieft) to incorporate an upper-radius arm. This proved to generate poor geometry and evil handling and, therefore, Nichols chose to restore the car back to the original “press release” specifications. As such, despite the fact that the Lloyd Roach heat exchanger proved unsatisfactory in period, Nichols had managed to successfully incorporate a modern version manufactured by Laminova.

Chassis #2 appears to be the car campaigned by English privateer David Prophet. Careful examination of period photographs and sifting through layers of paint suggest that chassis #2 was not one of the three works cars. There are small differences such as the radiator outlet canards and lower cut windscreen, which look to match period photos of David Prophet’s car at Snetterton in 1961.

Chassis #2 was Prophet’s first true racecar. Prophet traded in his Elva Courier, which had been constructed from a “kit” to offset expenses. Purchase price for the Kieft “less engine” was £950.00 according to the sales invoice dated September 21, 1960, while Prophet insisted on taking a personal hand in the construction of his new Kieft. Prophet went on to be the most active and successful Kieft Formula Junior driver. In 1961, among a number of good finishes, he took two 2nds at Mallory Park on May 27 and September 30 and another 2nd at Aintree on August 26. Prophet went on to be a highly successful privateer including a foray into Formula One.

Driving the Kieft

Photo: Nichols Collection

I’ve driven quite a few small formula cars, and I have to say that I love them. Sliding into one is like slipping into a custom-made shoe—however, in the case of the Kieft, it was like slipping into someone else’s shoe! Period Kieft sales literature described the car, “as one of the smallest Formula Juniors ever produced!” Yah, I can vouch for that.…

At six-feet tall, my body was not what Ron Timmins had in mind when he designed the Kieft. It took a fair amount of wiggling, scrunching, and sheer force of will, to get myself in a position where I could drive the car. The biggest problem was my long legs. With my upper body more reclined in the seat, my knees were jammed up under the dash hoop so solidly that I couldn’t work the pedals. In the end, I had to opt for pushing my hips back and sitting more upright in the car, which is why, if you look at our accompanying photos, my head looks like it is three feet above the roll hoop!

Once situated in the car, it took just a flick of a switch and the push of a button to coax the 1,098-cc, 4-cylinder, pushrod engine to life. With some effort, I was able to figure out how to make my left leg work—in the unnatural, yoga-esque position it was in—to depress the clutch and select first gear. Of course, even selecting first gear takes a moment of extra thought, as the Kieft is fitted with a modified Renault Dauphine gearbox, which, due to the linkage arrangement and its left-side placment, means that the shift pattern is the opposite of what one normally would expect, in other words, first being all the way over to the left and back. With a small amount of accelerator, and a slip of the clutch, the Kieft seamlessly pulled away and burbled along the paddock, toward the track.

Fortunately, after several failed attempts to make our schedules jibe, Marc and I finally came together at Laguna Seca, to test drive the Kieft, during a midweek HMSA event. In my mind, this was a perfect place to test the Kieft as (1) it’s a fabulous track for a formula car, (2) the weather was gorgeous, and (3) I know the track well, which diminishes the chances of my falling off the circuit!

Pulling out of the pit lane and onto the track, I give the Kieft a brief surge of throttle and am pleasantly given back a growl from the little Ford 105E and a healthy surge of acceleration. Right off the bat, the Kieft feels agile and precise. Entering the track, just past Turn 2, I give the Kieft a squirt of accelerator and upshift into second before I turn into Turn 3. As I commence my turn-in, and begin to squeeze on the gas, I’m immediately struck by a keen sense of precision from the car. The turn-in is both instantaneous and surgically precise. As I hit the apex, the Kieft starts a lovely drift out of the corner that, despite cool tires, is so smooth and predictable that it brings a smile to my Nomex-clad face.

After exiting Turn 3, it’s a “thoughtful” upshift to third, before I lift, turn-in, and accelerate through the broader Turn 4. Drifting to the outside of the track at the exit, I’m able to accelerate harder up into fourth and let the Kieft stretch its legs a bit, before I get on the binders for the entrance to Turn 5. With the Kieft being a drum-brake car, I have to confess to being a little uncertain as what to expect when I “stood” on the brakes, but I was pleased to feel an immediate bite and solid deceleration, as I approached my turn-in point. Between the favorable camber and the uphill exit, I’m able to hustle the Kieft through Turn 5 with another grin-producing drift.

Accelerating up the hill, toward Turn 6, the Kieft pulls hard, but with a tweaked 1,098-cc-cc engine, there is only so much torque a Junior can muster. With a lift and flick I’m through Turn 6, and accelerating up “Rahal Straight” toward the famed “Corkscrew.” Regardless of the speed or type of car, there is always a moment of faith near the top of the hill where, for all intents and purposes, you appear to be accelerating directly into the sky, with no clue as to what direction the track goes, or in fact, if there is even any more track left! Fortunately, as I crest the hill into the braking zone for the Corkscrew, I’m relieved to see that they haven’t moved the turn since the last time I was here! After a moment of untangling my feet from the mess they were in under the dash, I downshift back to second, flick the nimble little Kieft left into the turn and then immediately back to the right, as my right foot goes down and my stomach comes up. Diving down through the Corkscrew, the Kieft takes the sudden weight transfer and elevation change with aplomb as the G’s and acceleration load the suspension on the way down the hill toward Turn 9.

Turn 9 (as outlined in last month’s “Hot Laps”) is fast and can have some reasonably ugly consequences for being misjudged. Picking what I think is a reasonable entry speed and line, I set up the Kieft and then hold the line as the car dips down into the apex and slingshots out to the verge on the other side. Despite my size and seating concessions, the Kieft is now starting to feel like an extension of my hands—no sooner do I think about turning the car, than it is already moving in that direction. Like so many Formula Juniors and Formula Fords I’ve driven, there is a sense of precision in the way that the car handles that leaves the driver believing that he should be steering it with just the thumbs and index fingers. Hyperbole? Yes, but once you’ve driven one, you’ll see what I mean.

Turn 10 is another quick, camber-favorable kink that the Kieft squirts through, before it is back hard on the drum brakes, and down to second for the tricky Turn 11 that leads back onto the front straight. In an ideal world, the Kieft would take this turn in first gear and would get a nice launch onto the front straight, but since the car is equipped with the Renault gearbox, which is notoriously weak and prone to severing input shafts under load, I opt for the softer option and hustle the car through in second, being cautious not to loop it, exiting onto the straight! From here, it was hard up through the gears with a high-speed shot up and over Turn 1 at the crest of the hill, before settling into a few more tasty laps.

In case you couldn’t tell by now, I thought the Kieft was a delight to drive. What’s interesting is that, like a number of other more obscure historic racecars, the Kieft was not necessarily a front-runner in its day, but thanks to continued tuning and refinement on the part of Nichols, is quite capable of being a front-runner in modern Formula Junior fields, despite being a drum-brake car. If I were to wake up one morning with 4–5 inches of my legs missing, I’d seriously consider one.

Specifications

Chassis: Multitubular spaceframe

Wheelbase: 6’ 11”

Track: 4’ (front and rear)

Length: 10’

Width: 4’ 6”

Height: 2’ 10”

Steering: Kieft rack and pinion

Suspension: Front: Independent via unequal length wish-bones, coil-over damper units and anti-roll bar. Rear: Independent via upper wishbone and lower reversed wishbone with single radius rod and coil-over damper units.

Engine: Inline, 4-cylinder Ford 105E, developed by Arden

Displacement: 1,098-cc

Carburetion: Twin Weber DCOE sidedraft

Gearbox: Modified 4-speed Renault Dauphine

Clutch: Borg and Beck 7.25” single dry plate

Wheels: Kieft cast Elektron

Brakes: Outboard 9” Girling drum, front and rear

Resources

Hodges, David, A-Z of Formula Racing Cars, Bay View Books, 1990, ISBN 1-870979-16-8

Moss, Stirling, Stirling Moss: My Cars My Career, Haynes, 1987

Iota, March 1953, Motor, Sept. 21, 1960

Documents and letters from Lionel Mayman

Documents, letters and photographs from Steve Griffin, works mechanic

www.500race.org

Special thanks go to Marc Nichols, both for intrusting the author with his “pride and joy” and for his extensive research and help in writing the history of Kieft in this article.