1971 Alfa Romeo GTAm

There is a slight inclination here to refer you to Tony Adriaensen’s remarkable tome Alleggerita and let myself off a complex historical hook. Explaining the evolution of Alfa Romeo’s competition models is challenging at best and maddening most of the time. After about 25 years working on it, I’ve almost got it, but I never trust my memory without referring to the proper experts. Many people have tried to tell the story of Alfa Romeo and they all struggle when it comes to the subtleties of certain models and their variants. Belgian Adriaensen is the person who has done the best job of recording the twisted tale of how Giulia coupes and sedans became enormously powerful, wide-bodied wailing super-racers at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the ’70s. But as Alleggerita, the biography of the Alfa GTA, is virtually unobtainable, it falls to us to try to show you where the car you see here, the GTAm, came from.

Giulias from Giuliettas

The return of Alfa Romeo to international sports car racing and ultimately to Grand Prix competition in the 1970s (after departing the scene in 1953) can be traced back to one car, the Giulietta Sprint Zagato. This was Elio Zagato’s brainchild and grew out of his own enthusiasm for and, talent at, racing. These cars did very well in the hands of privateers in both racing and rallying, and were at their best where top end performance and endurance were essential requirements. Between 1958 and 1963, these SZs scored important class wins at the Targa Florio, Monza, Daytona, Sebring, and at the Alpine Cup Rally, which they won overall. The 1,300-cc engines were very quick but the Giulia model had been introduced and in 1963 it was the Giulia Tubolare Zagato or TZ with a larger 1,570-cc motor that became the racing successor of the SZ. The TZ had a tubular space frame with independent rear suspension and beautiful Zagato bodywork. These cars would be at the forefront of Alfa Romeo’s reappearance in sportscar and GT racing.

The existing regulations meant that at least 100 of the TZ model had to be built to be homologated into the sports category. The construction was thus contracted to a small company in Udine, in Northern Italy, which had been specifically brought together for the task. The Chizzola brothers, Lodovico and Gianni, had been running a tuning outfit called DeltaAuto, and when Carlo Chiti became a founding partner, this became Autodelta which was the Alfa Romeo racing division for many years. Alfa also had a development center in Milan, which did the additional race preparation of the TZ for privateers. Autodelta later moved to Milan under the direction of Chiti, and the racing program expanded dramatically into sports cars with the Tipo 33 and, of course, into touring car competition on a large scale.

The popularity of touring car racing, and the luxury of having a good touring car, which would also do well in endurance events, brought about the birth of the GTA. The GTA was based on the production Giulia Sprint GT, the Bertone-bodied 105 series coupe. On reflection, understanding the evolution of the Bertone coupes is very difficult indeed, as there was a very large list of variants, with numerous engine capacities, over a long time period. The Sprint GT had the easily recognized “step-front” nose, with the leading edge of the bonnet raised slightly higher than the front panel. The GTAs were thus recognized by their “step-fronts,” though in typical Alfa Romeo fashion, there were exceptions and with later mods, not all had this unique step-front. Many of the next level GTAm cars had the step-front, but then again, some didn’t. I hope you are following this!

Just what was the GTA? The basis of the GTA was a standard Sprint GT which had been seriously lightened, or “alleggerita” in Italian. Everything that could be removed, especially all the sound-deadening material in the production Sprint GT, was duly removed, and the steel panels were replaced by alloy, as were the wheels. Some 200 kilos were saved this way, and in combination with a more powerful engine, the GTA was very much a transformed machine. The GTA unit was fitted with a twin-plug head, had larger valves and a 9.7 to 1 compression ratio. The first cars produced 115 bhp and had a top speed of 115 mph. The cars raced by Autodelta were developed even further, were 45 kilos lighter, had a 10.5 to 1 compression ratio and produced 170 bhp @7,500 rpm. These cars also had a limited slip diff, an antiroll bar, stronger suspension and extra oil coolers.

The GTAs were enormously successful through 1966, ’67 and ’68, especially in the hands of drivers like Jochen Rindt, Andrea de Adamich, Toine Hezemans, Nanni Galli, Ignazio Giunti and Teororo Zeccoli, having memorable scraps with the Lotus Cortinas of Sir John Whitmore, Jacky Ickx and Frank Gardner. In long endurance races, they were sometimes only beaten by the overall winning Porsche 911s.

The GTAm

Group 2 touring car racing was another place where the GTA was doing very well in 1966 and 1967, but Group 5 allowed much greater modifications to a standard car. In ’67, Alfa decided to put 10 GTAs aside and convert them to Group 5 rules by means of supercharging, using twin turbine-driven blowers. The engines in these GTA-SA racers could produce a staggering 220 bhp @7,500 rpm, with a top speed of 150 mph.

The so-called standard GTAs won the European Touring Car Championship in 1967 for the second time, with Giunti also taking the European Hill climb Championship. The GTA won the ETCC again in 1968, and was joined in that year by the GTA Junior, the 1,300-cc version of the GTA. Between 1968 and 1972, 447 of these cars were built of which some 300 were built as competition cars. Like the bigger 1,600-cc GTA, the GTAJ got the same Autodelta treatment for selected customers with engine and suspension improvements.

In January 1968, Alfa Romeo presented to the press a Berlina version of the new 1750 model, another Giulia, with a larger engine. Like the earlier Giulia saloons or berlinas, this one was rather square in shape but, with the bigger 1,779-cc engine, the performance was impressive. In July, four of these cars with the saloon body ran as Group 1 standard cars in the Spa 24 Hour race…and took the first four places. The coupe 1750 GTV then followed into Group 2, 3 and 5 races, all being modified to suit the class rules. From the moment the 1750 GTV was homologated into Group 2 in April 1969, extensive changes were made to the basic 1750 chassis and components to make it more competitive and successful. This included increasing the engine capacity to 1,985-cc as Group 2 allowed engines up to 2-liters. The bore was increased from 80 to 84.5-mm and the stroke of 88.5-mm was retained. The respected historians Hull and Slater state: “As it was still desirable for publicity purposes to link the car with the production 1750, the little ‘m’ was placed after GTA signifying maggiorat or enlarged, hence GTAm.”

There were two consequences of this event: many people considered the GTAm to be a modified GTA, and that the “m” did indeed stand for “maggiorata.” Tony Adriaensen and subsequent historians, including the author, contest this. To some extent this is an academic argument, as the basic Giulias were all very similar. Adriaensen contends, “The GTAm was nothing more than an improved version of the standard GTV.” Chiti had the GTAm homologated in its own right, though that was not strictly necessary as the rules allowed generous modifications. The use of Spica injection did not present any problems in the process of homologation as more than 1,000 cars (the 1750 GTV USA) had been produced with Spica fuel injection for the American market. It was indeed the elaborated GTV, which was homologated, not a GTA. The papers for this model had several pages listing the GTAm modifications including the special cylinder head with twin ignition.

Adriaensen: “It is said the letter ‘m’ stands for the Italian word ‘maggiorata,’ which means increased and refers to the cylinder contents increase from 1,600 to 2,000-cc. I myself choose to believe another explanation, namely ‘American,’ since we are not dealing with a GTA at all. The ‘A’ normally stands for ‘alleggerita,’ which is the Italian word for ‘lightweight’ by making use of aluminum bodywork. In this case the GTAm had standard, full-steel coach work modified with aluminum and/or plastic parts.” Of course, it is not beyond the realms of possibility that Alfa Romeo was happy to have “GTAm” meet both sets of definitions to appeal to a wider audience, and even within the company there have been times when different people explained such phenomena in completely different manners!”

The standard 1750 block was the basis of the GTAm engine, and some cars did indeed race with the smaller capacity head. But most engines were quickly built to the larger spec between 1,985 and 1,999-cc. In the 1,985-cc unit the bore was increased but the stroke remained standard, but by using this process of enlarging the bore, the four-cylinder liners no longer fit into the engine block. This led to the liners being cast as a single unit, the so-called Siamese liners or monosleeves, which were unique to the GTAm. These were actually glued into the block with Araldite. Smaller pistons were also required.

To confuse the issue even further, the GTAms were homologated with the alloy doors and door handles of the GTA but not all GTAms had them! Indeed, by 1972, there were GTAs with narrow and wide bodies, GTAms with wide bodies and then the GTA Junior with the wide body. The “step-front” nose distinguished most, but not all, cars, and most GTAms had a single headlight on each side…but not all! Thus, at a race where all models were present, only the very knowledgeable could tell what the car passing in front of them really was!

The GTAm in Racing

The number of racing GTAms built has always been disputed, but the estimate ranges from 40 to 60, though the smaller number is more likely, and even that may be an overestimate. The number of cars converted from either GTAs or GTVs into GTAms has helped to confuse the issue somewhat as these were done in period and were accepted in events as genuine GTAms, and for all intents and purposes, they were genuine as they started with something that was close to a factory-built GTAm and was modified to GTAm specs.

Dutchman Toine Hezemans was a real star in the GTAm. He had been approached by Chiti to drive for Autodelta and he was so good that he was the main test driver during the development of the GTAm. He had his first race in the car at the Monza 4 Hours in 1970, where Spartaco Dini was on pole, Hezemans 2nd quickest, Facetti/Zeccoli 3rd and Belgian Christine Beckers, with Enrico Pinto, was 4th. The opposition was mainly BMWs and 2.3-liter Capris, but Hezemans quickly moved into a lead he wouldn’t lose. At the Salzburgring, he led again but a fuel pump fell off, though he managed 2nd behind a BMW 2800CS. Hezemans then dominated again at the Budapest Grand Prix and led the European Championship. While the Fords and BMWs were not as reliable as they needed to be, the Alfas were clearly the class of the field, and the weight of numbers just wore down the opposition. At Brno, in Czechoslovakia, Toine won again, was 2nd at the Tourist Trophy in England, and crashed at the Nürburgring. After winning the Spanish round at Jarama, Hezemans had taken the European Group 2 title, and the GTAm won an additional 16 races in 1970. Leonibus won the 2-liter touring class of the Italian National Championship. It had been a very successful year.

When the 1971 European Touring Car Championship opened at the traditional Monza race, it was déjà vu as Toine Hezemans repeated his win of the previous year. This time he was up against much stronger Ford Capris and Escorts, and he didn’t take the lead until very near the end of the four-hour event, and one of the BMWs followed him into 2nd place. At Brno, the Dutchman only got a class win, which he repeated at the Nürburgring sharing with van Lennep, taking 2nd overall. At the Spa 24 Hours, there were five GTAms, three works cars and two Belgian private entries. Hezemans had several long stops to change a head gasket and then his radiator, and spent the rest of the race working back up to 3rd overall and 1st in class behind a Capri and a Mercedes. The Dutch driver then had a class win at Zandvoort, was 3rd at the Paul Ricard 24 Hours and was a championship-winning 2nd at Jarama. The GTAm continued to win a large number of non-title events, and did so again in 1972 and 1973, though Autodelta reduced its works program in 1972 and left the fighting to privateers, who continued to win.

The Monzeglio Mauler

One of the long-standing and successful Italian privateer teams was Squadra Corse Monzeglio, which was running a number of racing Alfas from the late 1960s into the 1970s. In addition to their major concentration on the Italian Touring Car Championship, they had a GTAm in the Monza 1,000 Kilometers for Zanetti in 1970, and entered GTAJs for Luigi Pozzi/Mario Zanetti and Picchi/Dini in the Monza 4 Hours in 1972. They also had a quick Lola T212 with an Alfa 2-liter engine in the 1972 Targa Florio where Zanetti and Locatelli finished a competent 8th overall. They even went as far as the German F3 Championship in 1974 where they raced a GRD-Ford, one of their few ventures away from Alfa power.

The car you see featured here, chassis AR 775092, was a Squadra Corse Monzeglio team car from 1969 through 1971. Now, before you chassis number fanatics go wild, let’s backtrack in the story a bit. Remember where we said that there were GTAms and GTAms? Well, this is one of the latter! Now that means it was not one of the cars with a 153**** serial number, the GTV-based GTAms built from 1970 on. But this is a GTAm!

AR775092 started life in 1968 or 1969 (the Fusi bible manages to list this chassis twice!) as a 1,300-cc GTA Junior. It was sold to Squadra Corse Monzeglio, Via Cabotto 35, Torino and it raced as a team car from 1969 to 1971. It ran first as the GTAJ that it was in the Italian Touring Car series, mainly driven by Luigi Pozzo, though he was not the only driver. At the end of 1970, the car was converted to GTAm specifications but used a 1,300-cc, fuel-injected, eight-valve engine, and with this set-up Pozzo won the Italian Touring Car Championship. Pozzo then had 20 wins in 1971, and toward the end of that year, it was converted with a 1750-based engine and GTAm 16-valve head, which gave a capacity of 1,992-cc with Spica fuel injection. It then ran in the GTP class and had further wins including the Bruno Deserti Trophy at Imola in September and the Coppa AC Torino in October. It is also interesting that through this long period, the car retained its road registration…TO B14679…which was necessary for some of the races on public roads. It remains something of a mystery as to how many GTAms had 16-valve as opposed to 8-valve heads. The jury is still out on this one.

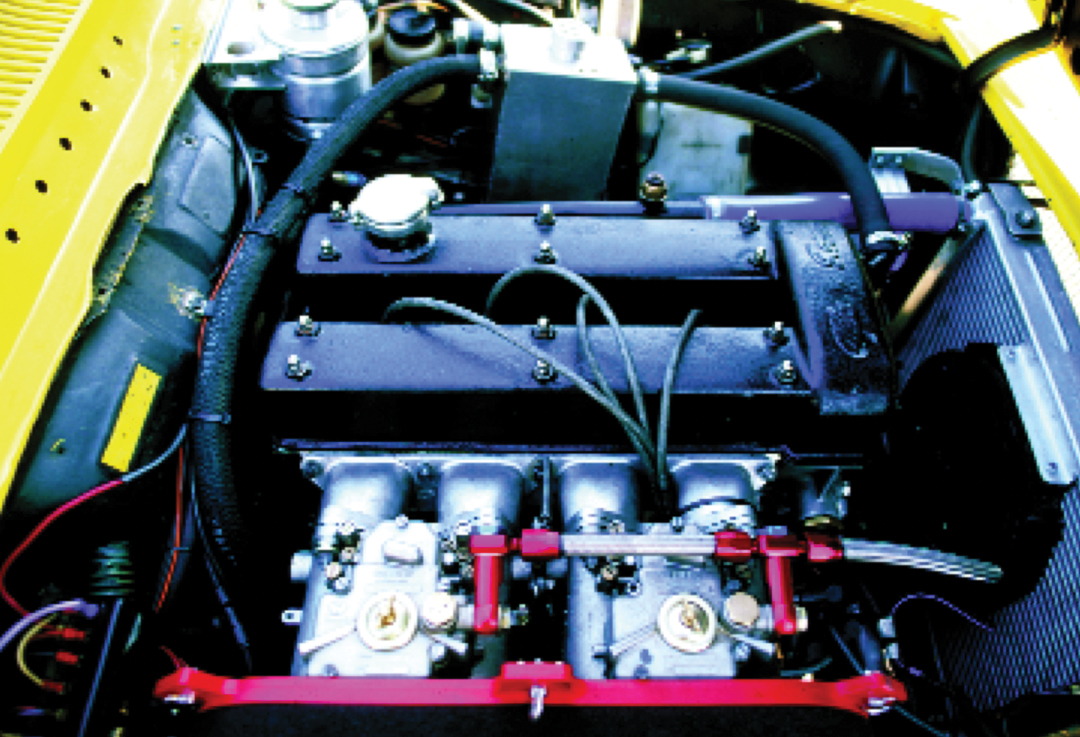

The car was sold to Rudi Franz, a Brazilian who lived in Switzerland, and he did a number of races between ’72 and ’75. It was put into a protective storage unit in 1976 where it remained until 1996 when it passed into the hands of Robert Fehlman but was looked after by Siggi Brunn. Brunn did what would appear to be a sensitive restoration and the car appeared in the Tour Auto in 1997, with an 8-valve, 2-liter motor. It then was sold in 2000 to John Ruston and came with the 1,300-and 1,992-cc engines disassembled, and it was built up by Gareth Burnett, who prepares and races cars for Ruston and others, with the 1,992-cc unit with 16-valve, single-plug head but on carburetors. The 2-liter, 16-valve heads are single-plug rather than twin-plug heads. Gareth Burnett drove the car in the Tour Auto in 2003 with a borrowed 8-valve engine, until the 16-valve one was finished, and that appeared in the Tour Auto in 2004.

Driving the GTAm

Gareth says the car was and is set up for the circuit stages of the Tour Auto, and on the circuits it was extremely quick. On the dyno the engine is showing 230 bhp and that accounts for very considerable poke in quite a small car. With massive torque, it was capable of running at the front at the circuits, even beating much lighter Elans. The handling was good, with a feeling of controllable balance. A fair amount of testing had gone on before the Tour to achieve this, though the GTAm in period was found to be a real handful for many drivers. Testing led to the use of stiff front springs, but it still had a degree of bump steer on the special Tour stages and rougher sections. It apparently went very well on the smooth sweeps of Dijon, yet proved tractable on the road.

So, we decided to find a mix of tarmac to do this test, and that involved some long, open-road sections in deepest Suffolk, with a touch of damp weather, and a second chance on dry fast roads with a twisty wooded section and a heaping of mud! This gave plenty of variety, tested the 5-speed gearbox and the brakes, and provided scope to feel the stunning acceleration and torque, and generally just settle down into this fine road/race machine. The car sits on Yokohama Advan 023R tires—205/50R15 at the front and 225/50R15-91V on Minilite wheels and looks mean. Inside it’s standard-ish…that is, you can see the production origins. It does feature a modified gearshift with remote change. I had the excitement of having the nut that locks the remote change come loose and the whole assembly drop to my feet at an unwelcome moment! That was quickly fixed…twice…and the gearbox works like a charm. It’s usual Alfa 5-speed with first left and back and then a conventional H-pattern for the other four gears.

Having raced standard Alfettas, FIA Giulia Saloons, Suds, 33s, 156s, a modified GTV amongst others, I was really expecting the GTAm to be something of a beast. It did do everything quicker than all the above…got off the line quicker, took the bends quicker, and stopped much quicker. The low-down driving posture helps you feel what the car is doing and the superb balance was rewarding on quite dodgy roads, with bumps, wet spots and a bit of mud.

The rev counter reads to 10,000 rpm and the Speedo to 240 kph, but we weren’t going into those areas. Nevertheless, on some private and isolated piece of swooping roadway, it was possible to squeeze a real sense of the thrill inherent in this famous old beast. The rorty noise was there, the quick responsive handling once up to speed, all inspiring confidence in blasting into and out of corners at rude speeds! While the GTAm was magnificent at Monza, Spa and all the high-speed venues, here it was flying low on tough bits of road. Unexpected, but great. There was a moment tearing up a long hill with a crest at the top and a sweep to the left, all blind. The GTAm just dug in and went around, and whistled away into the distance. Lovely car for an Alfa-lover.

Buying and Maintaining a GTAm

Because there were so many 105-based coupes racing in the 1960s/70s, many cars survived. These include the whole range of competition models and, once you leave the Sprint GTs and GTVs behind and move to GTAs, GTAJs and GTAms, they get rarer and they get pricier. There are GTAms on the market that are bringing enormous prices and they are recent conversions and shouldn’t really count. The number of surviving GTAms which were built as GTAms with 153 serial numbers is very small. This car, which started life as a proper GTAJ and was a racer from its beginning, was beautifully converted to GTAm specs, has its two original engines, won the Italian National Championship, is spectacular to drive, and is a competitive historic racer. That means the price has to come in at some 160,000 Euro or $180,000. That’s at the top end, where it needs to be.

Specifications

Type: 105.59 GTA Junior chassis, full conversion to GTAm

Year of production: 1969

Engine type: GTAm

Cylinders: 4

Cylinder head: 16-valve, single-plug head

Capacity: 1992-cc

Power: 230 bhp

Gearbox: Alfa Romeo Autodelta race box

Wheelbase: 2350 mm

Front track: 1350 mm

Rear track: 1300 mm

Weight: 790 Kgs.

Maximum speed: 230 kph

Tires: Yokohama Advan 023R, front: 205/50R-15; rear: 225/50R-15

Resources

Thanks very much to John Ruston and Gareth Burnett (www.gbraceengineering.com) for their generosity and help.

Adriaensen, T. Alleggerita. Corsa Research Production, 1993. Antwerp, Belgium.

Fusi, L. Alfa Romeo—All Cars from 1910. Emmeti Grafica, 1978. Milan, Italy.

Hull, P. and R. Slater. Alfa Romeo: A History. Transport Bookman Publications, 1982. Tunbridge Wells, Kent.