1960 Jolus Formula Junior

“Fair Dinkum?” Was my response to the question. Fortunate would be a good way of describing it. “Bloody lucky” would be another way. Writing about older racing cars is enjoyable enough but being asked to have a run in someone’s pride and joy is even better again.

“Would you like to have a drive?” Was the question and, yes, they were sweet words indeed. We had just come to the end of a successful historic race meeting at Oran Park in Sydney, Australia. Competitors, friends, and spectators were enjoying a beer or two while exchanging stories of heroic exploits over the weekend. I had known Geoff Fry for close to 30 years and was chatting with him about how he went over the weekend behind the wheel of his Ford-powered Vulcan sports car.

After my blurting of yet another word or two from the great Australian collection of vernacular, Geoff then said, “Why don’t you come and have a run in the Jolus at a GEAR meeting at Wakefield Park?” I’m normally the one doing the asking so I was a little lost for words when the roles were reversed. However, I very quickly managed to regain my composure and asked if he was sure. “Yeah! Why not? It would be fun.” A few days later it did occur to me that Geoff may have just been caught up in the post race meeting enthusiasm (plus the odd cold one) but, no, a phone call confirmed it.

Being an inquisitive sort of bloke who also just happens to have a slight obsession with automotive and motor racing history, I needed to know more about the car that I was to drive. Over the next few weeks I spoke to Geoff about his Jolus Formula Junior and how he had not long beforehand finished its restoration. It was built during the early 1960s by a Sydney-based motor racing enthusiast by the name of Bob Joass who went on to build three similar cars until he suddenly just stopped.

This sounded a bit interesting, especially why someone would all of a sudden build a batch of open-wheeled racing cars and then disappear. There had to be an interesting story in it and I wanted to know more.

Over Lunch

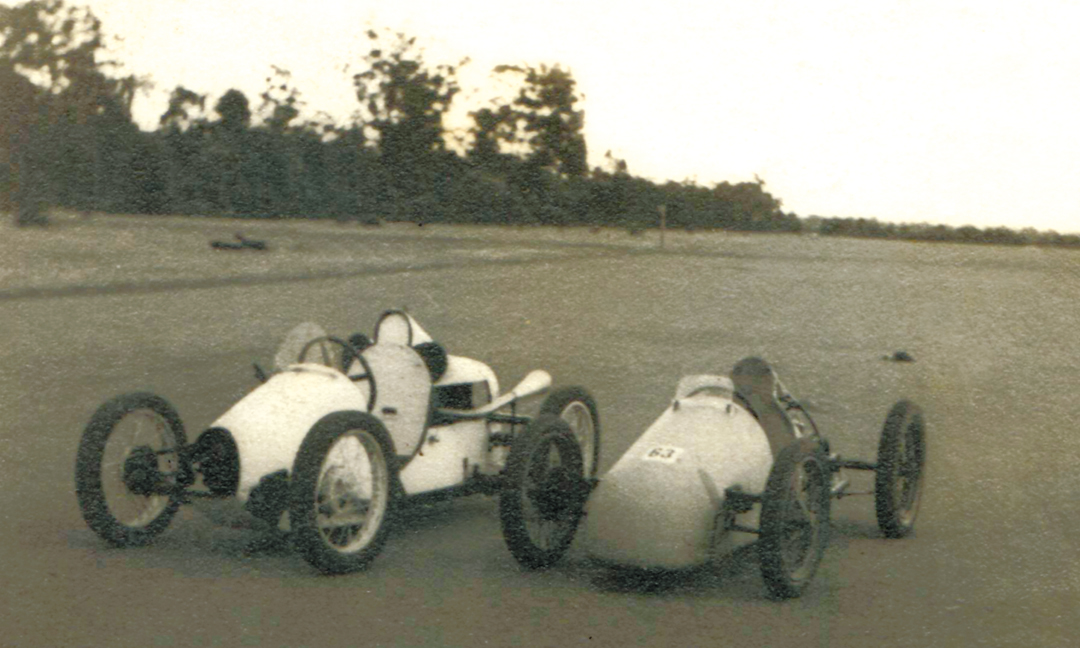

Photo: Steve Oom

It’s funny the things we find ourselves doing. A couple of years ago I let myself be talked into attending a lunch with a group of Lotus Elite owners. I’ve never owned a Lotus, let alone an Elite, but it seemed like a good idea at the time to attend and listen to the usual collection of tall tales but true. The lunch didn’t stop at just one and has now evolved into almost a bimonthly excuse to sample some Italian tucker, a glass of red, and automotive prattle. They have even given the group a name: LEADFOOTS, short for Lotus Elite Association of Drivers, Followers, Owners, Operators, Tinkerers, and Suchlike. I feel quite at home being classified as a Suchlike.

A few months back I went along to another Elite extravaganza and after settling down with a cleansing ale noticed Brabham-and Ralt-designer Ron Tauranac sitting in the corner deep in conversation with another bloke. From the amount of scribbling being applied to the paper tablemat it was clear they were deep in conversation on something a little grander than tinkering.

Later when the pen wielding had died down somewhat, I said hello to the man who is arguably the most successful racecar designer of all time and, in turn, Ron introduced me to his close friend, Bob Joass! The fickle finger of fate sometimes has strange ways of playing its hand and I quickly made arrangements to meet Bob to talk with him about his time as a racecar builder.

Teenage Enthusiasm

As it turns out, there was more to Geoff Fry’s Jolus Formula Junior than met the eye. In fact, it goes right back 12 years before it was built when, in 1948, a 16-year-old Bob Joass was fired up with teenage enthusiasm. Bob had become interested in motor racing and had read a magazine article on air-cooled open wheelers in England and decided that he wanted to be involved. Like many countries worldwide, the immediate post-WWII period in Australia was a time of austerity with very few resources available. In Bob’s words, “You couldn’t get anything, and I knew nothing.”

However, despite the deprivations, there was a thriving motor racing scene in Sydney with much of it centered around the 500 Car Club of New South Wales. Bob quickly became a member and, at the first meeting he attended, met up with an equally youthful Ron Tauranac and his brother Austin. Bob and Ron became firm friends and have been so ever since.

Photo: Steve Oom

With his interest fuelled with what he had heard at his first meeting, Bob was even more determined to build an air-cooled racing car. However, besides knowing nothing, Bob was somewhat restricted by his £5 a week wage as a telephone technician plus, not only did he not own a car, he didn’t even have a license—and on top of all that had never even driven a car!

Undeterred, Bob set out to build his first car starting with a trip to the local wrecker where he bought a chassis from a 1928 Singer 9 that he carried home on his shoulder. From the same wreckers came a front axle, wheels, and front transverse spring from an Austin 7, and a 1924 Oakland steering box. Equipped with a 1928 Model-18 Norton engine and BSA 3-speed, gate-change gearbox, he was ready to go.

Sprints

To give the young Bob Joass his due, the Joass 500 was finished and even ran competitively in a couple of sprint meetings. It was at one of these meetings in early 1948 that Ron Tauranac brought along his first creation called Ralt. A name coined from his initials and that of his brother Austin.

To put it in Bob’s words, “I hadn’t seen what Ron Tauranac was doing but when I did I felt like falling through the ground, as I was so ashamed at what I had done. It was 1948 and there just wasn’t anything else around.”

However, the Joass 500 did serve a purpose as by this stage Bob had his driver’s license and needed a car so it was swapped for a 1923 Buick Tourer. Not long after, having saved a few dollars and having learned quite a bit from what Ron Tauranac was doing, Bob set about building his next racing car. In fact, it followed the design of Ralt 1, with Ron’s permission, by using parallel tubes forming a U-shape at the front and steering by the use of a Ford Model T epicyclic steering box. Bob spent much of his time visiting the Tauranac brothers at Austin’s garage in the middle of Sydney, amazingly only a stone’s throw from where the Sydney Opera House is now located.

By this time, Ron Tauranac was also moving on with his designs and had developed a low pivot-center for the rear end of Ralt 1 and so the whole of the older-style rear end was fitted to Bob’s car. However, as Bob was still on a limited wage, funds were tight. Help came along in the name of Ashton Marshall, a Sydney used-car dealer who saw the car and offered to buy what was there and provide the necessary cash to have it finished. The car then became known as the Marshall 500.

Fitted with a Triumph Tiger 100 engine and gearbox, Marshall ran the car at Bathurst where it holed a piston. Disenchanted with the car Marshall traded it in on a Mk IV Cooper JAP that Bob fettled for a while. Marshall eventually became involved in Top Fuel Dragsters, moved to the United States, and set up shop in San Diego, California, selling cars.

First Junior

Next followed a series of air-cooled cars for various friends and customers. However, the cars themselves were getting slightly bigger and were fitted with larger engines such as the Triumph Thunderbird and Ariel Square Four. Later, an even larger vehicle fitted with a BMC 1,500-cc, four-cylinder engine and VW split-case gearbox followed, plus others fitted with mainly VW mechanicals.

Unbeknownst to Bob, far off in Italy, a new style of competition car was being considered. It was the idea of Count Giovanni Lurani to introduce a new formula that would be economical to build and act as a training ground for young drivers. Introduced in 1958, we now know it as Formula Junior and it proved to be phenomenally successful throughout the world.

Then, out of the blue, Bob was contacted by local racing driver Ron Smith to build another car. To this day Bob has no idea how Ron found out about him, but the car was to be the first of the Jolus Formula Juniors. It was 1960 and Bob says that he thought he had matured by then so, instead of launching into welding up lengths of steel, he actually sat down and designed a spaceframe chassis. It also gave Bob the incentive to fully establish his racing car business.

A completed cost of £1,500 was agreed upon including the price of a new Ford 105E engine. Bob had to think of a name but was rather intrigued that the names of many of the larger manufacturers all had the letter L in them, such as Lotus, Lola, and the like. So, by simply adding an L to his own name, he came up with Jolus. He went one further and, through the help of a customer, had a series of badges made for hopefully a future line of Jolus cars.

Cooking Engine

Bob made it quite clear to Ron Smith that, while the cost of the car included an engine and split-case VW gearbox, he didn’t want to be involved in the preparation of the engine. So a standard 105E engine was bought from a Ford dealer for £375 and Bob made up the mating plates to suit the VW box. Bob Britten (later to produce the Rennmax range of open-wheeled racing cars) was called upon to make the uprights with “Jolus” suitably cast into them and also cast up the wheels that were not unlike those used by Cooper, but cast in aluminum. A body in alloy was also produced.

Though the car was now up and running, Bob unfortunately, couldn’t really describe its new owner as a star driver. Now, after close to 45 years, passing through many owners and freshly restored by Geoff Fry, I was offered a drive.

Jolus 1 was no sooner out of the way than along came enthusiast Paul Bolton who simply arrived at Bob’s house one day and walked up the driveway. He introduced himself and asked if Bob would build him a Formula Junior car the same as Ron Smith’s but fitted with a Formula Junior Cosworth engine he had acquired. So Bob built his second Formula Junior, which in this owner’s hands turned out to be quite successful. However, Bolton pranged it at Warwick Farm later and subsequently Jolus 2 was broken up and some of its parts went on to form the basis of a Lotus 23 look-a-like called the Sterling.

Third Jolus

By this time, Bob Joass was riding the crest of a wave because, no sooner than the car for Paul Bolton was finished, he was approached by a Hillman specialist who wanted a slightly more sophisticated car than a Formula Junior, built to take Hillman components. Bob agreed and put together another chassis but with adjustable pivot points for the coil-spring damper unit. Looking back, Bob says it was better built and a little fancier with such things as chrome-plated wishbones. Like Jolus 1, the Jolus Minx continues to be driven enthusiastically in historic events by Australian Peter Quayle who has owned it since 1968.

As with so many historic racing cars this is where the story gets a little difficult to follow. Not long after the Jolus Minx was completed, Bob was approached by the then-current owner of Jolus 1 to make up a spare chassis, set of wishbones, and obtain some uprights. For the sake of history, this could be called Jolus 4 but, over time, a number of components from Jolus 2 found their way on to it. The owner had heard that Bob was moving on to other businesses and, concerned that he might damage his car, thought it might be a good idea to have spares.

Jolus 4 was assembled into a complete car and raced, but many years later was restored with a fresh chassis and remaining components from Jolus 2. It was then sold to American racer Richard Buckingham who raced the car in historic racing in North America. Confused? You can be excused, as the original Jolus 4 chassis still exists along with many other components and is owned by Geoff Fry, the owner of Jolus 1.

A Place in History

Not long after completion of the fourth chassis, Bob Joass left the motor racing business completely and went to work for the Travelodge motel company. However, his cars certainly deserve a place in Australia’s motor racing history. Bob himself, many years later, did return to motor racing when in 1981 he bought an F2 Cheetah, less engine and fitted it with a 4-cylinder 750-cc Suzuki engine. This was swapped for a Lotus Europa that Bob used in competition events. The Cheetah in the hands of subsequent owners and powered by a supercharged Renault engine, went on to capture the Australian Hillclimb Championship.

Of course three Formula Junior cars are not that many when compared with the production from the likes of Lotus, Cooper and Lola. Yes, Jolus only built a few cars, but then again so did many other manufacturers around the world. It was a period when a spirited enthusiast could build a car that complied with the relatively simple Formula Junior regulations, enjoy themselves, and even make a quid or two.

GEAR Day

Motor racing in Australia is managed by the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport or CAMS. As you would expect, to run a race meeting requires reams of paperwork, sufficient insurances, approvals signed on the dotted line and as much red tape as possible. It’s a sad fact of life that all this is necessary in this day and age. However, what would happen if you don’t hold a race meeting but a gathering of like-minded enthusiasts who wish to drive their cars in an enthusiastic but noncompetitive way? Is it a race meeting?

GEAR or Golden Era Auto Racing Club was established to provide enjoyable motor sport for enthusiasts who want to exercise their cars but not necessarily in open or historic racing. It evolved from the Country Gents’ Days set up after the establishment of the Wakefield Park circuit in southern New South Wales a little over 10 years ago.

A GEAR day is not an organized race meeting but a noncompetitive midweek day for members. While cars in classes are lined up on the track together, you don’t actually race against each other. What it ends up being is everyone racing against the clock. Passing is allowed but only when it’s safe, such as along the straight. Overenthusiastic driving is frowned on and will bring down the wrath of the organizers upon your head.

No Heroics

I was running late but as Wakefield Park is almost four hours from home I decided to use that as an excuse. I chose to ignore the fact that Wakefield Park is four hours away from the homes of most people. After the pleasantries, the paperwork, explaining who I am, filling out various forms and paying my money, I became a member of GEAR and have signed up for my Wakefield Park Club Competition Licence.

Next, I am drawn aside by GEAR president Terry Harris who talks to me in a fatherly way while explaining that the purpose of the day is to have fun and that, while out on the circuit, we should give everyone a wide berth with passing only when safe, like along the straight.

Lining up on the circuit brought back memories of my first time out on a circuit with other cars, in 1977 to be precise, almost a lifetime ago. It was a historic race at Amaroo Park when the temperature was way past 100 in the old scale. Terry Harris was there too, along with quite a few of the familiar faces who were at Wakefield Park. Only now the hair is a little lacking and somewhat grayer.

Behind the Wheel

Geoff was keen that I got to sit in the Jolus, but I don’t know if I was a perfect fit as, while I am a little shorter than Geoff is, I am a little broader across the beam. While the seat was tight; the pedals were somewhere down there past my feet. Being behind the wheel wasn’t exactly sitting down either, more like lying down in the dentist chair, and pushing the pedals was just possible, provided my ankles were being turned at angles they were never designed for. Thankfully, the gearshift was on the left.

Once I’m buckled up and familiar with the cockpit, I’m let out on the circuit by myself and up gingerly through the gears getting used to the Jolus and the circuit. Into fourth and suddenly it’s the end of the straight and hard on the brakes, while back to third and around to the right. It comes as no surprise that it goes around corners far quicker than the sedans I’ve test driven for VRJ. Up the slight incline to the back part of Wakefield Park, pushing it in third and into top before the right-hand sweeping corner. The circuit then gradually sweeps to the right, until a very tight left-hander.

Unsure how to best tackle this left-hander, I keep it in 3rd and find my way around the best I can. It’s a tricky corner that tightens the deeper you go. That’s followed by a further right-hand sweeper and a short straight taken in fourth. Then an off-camber, 120-degree right-hander that takes you back to the straight. I’m allowed five laps to get used to it all before it’s time to come in.

Geoff’s full of enthusiasm for what I thought. I’m full of adrenalin from the excitement. My first thoughts were how forgiving the car was. Next, it was Geoff’s turn to show me how it was done, especially when it came to getting into second for some of the slower corners, something I had yet to do.

Interesting Mix

My second time out was far more to my liking as I was now getting used to both the Jolus and the circuit. Well, at least I thought I was, until the dreaded left-hander. I went in too early and quickly found out that even the Jolus has a limit to its adhesion, when the front tried to swap ends with the rear. Red faced and embarrassed? Yes, you could say that, especially when photographer Steve Oom managed to capture me facing in the wrong direction.

Two laps later and I was still wondering who was boss, me or the left-hander, but at least I got it back to second. It’s amazing how quickly five laps pass. Later, I’m let out again, but in the company of a few other cars and I even manage to pass some. The left-hander is still a worry but I find second most times that I want to. It’s a huge amount of fun but again five laps goes far too quickly and so I finished my driving enjoyment for the day. Plus the engine is starting to miss at high revs and it’s becoming difficult to select lower gears. I tell Geoff later that it was all the fault of the left-hander.

Living with a Jolus FJ

I had a ball trying out Geoff Fry’s Jolus Formula Junior. I found the handling to be very neutral but there is a limit of adhesion that’s easy to find if you try, especially if you’re learning. The Ford engine felt very free and flexible right throughout the rev range and I was surprised at how well the upside-down and back-to-front VW gearbox suited the free-revving engine. Being tight, Wakefield Park does make it interesting on brakes but the four-wheel drums did everything my right foot asked of them and without any perceptible fade. While set up for someone taller than my 5ft 10in frame, I was surprised at how comfortable the car turned out to be, especially allowing complete freedom for maximum arm twirling, normally an area that I find difficulty with. If it was my car, I would set the pedals a little closer, but that was just a matter of adjustment.

According to Geoff, servicing the Jolus FJ is simplicity itself. From when the restoration was finished in 1998 to now, the Jolus has been run in 28 historic race meetings and still uses the same Hoosier tires! Geoff uses Australian Penrite lubricants exclusively and in the interest of engine longevity the oil is changed after every second meeting. Keeping the oil level correct in the VW gearbox is crucial but slightly difficult as it’s fitted upside-down. Prior to each meeting Geoff also goes over all nuts and bolts in the car, making sure that each is tightened. Geoff has tried to keep the car as close to original as possible—as Australian historic regulations demand “as it was, shall it be.”

Specifications

Chassis: Steel Tube Space Frame

Body: Hand Beaten Aluminum

Wheelbase: 7-feet 7-inch (2,330mm)

Weight: 882 lbs. (400kgs)

Suspension: Front: Independent with coils, over adjustable shock absorbers and antiroll bar. Triumph Herald uprights. Rear: Independent trailing arms, coil springs over adjustable shock absorbers, cast uprights with Holden hubs.

Steering Gear: Rack and pinion (Renault 750)

Engine: Four-cylinder, Ford 105E. 1,098cc (Standard crank)

Power: 95bhp at 6,500 rpm

Carburetor: Twin SU H4

Clutch: Single dry plate

Gearbox: VW Split Case – 39hp

Gears: 4 forward, 1 reverse

Foot Brake: 4 wheel drums (twin leading cylinders)

Hand Brake: Nil

Wheels: Composite – steel/cast aluminum

Tires: 5.00 X 15 Hoosier

Resources

Cowdrey, Bernard. Formula Junior; The Complete A-Z. Bookmarque Publishing, 2002.

ISBN 1870519-66-3

Web site: www.australianformulajunior.com

“Loose Fillings.” An occasional newsletter dedicated to the news and history of air-cooled cars in Australia and beyond. ([email protected])