1971 Trans-Am Javelin AMX

When the typical automotive enthusiast thinks of American Motors, usually the images that are conjured are of some of the greatest mistakes in American automotive history—the Gremlin, the Matador and, of course, the Pacer. However, fans of Trans-Am racing history undoubtedly think back to the halcyon days of 1970 and 1971, when Roger Penske and Mark Donohue took an ailing AMC Javelin Trans-Am program by the throat and turned it into a racing legacy.

Strangely enough, the starting point for this remarkable transformation was not a race track or glass-lined boardroom, but a dinghy motel room in Century City, California. The week after Mark Donohue and Roger Penske had clinched the 1969 Trans-Am Championship at Riverside with their Chevrolet Camaro, the duo found themselves sitting in said motel room with Bill McNealy, vice president of marketing for AMC. Though Penske had just convincingly won the championship for Chevrolet, he was having serious trouble getting the financial support from them that he felt he needed to back up that year’s stunning performance. In McNealy’s case, he had just wrapped up a fairly disastrous Trans-Am season running a Javelin program with Ron Kaplan and Jim Jeffords. Thus, the two businessmen had met, in this non-descript motel room, to see if there was common ground from which Penske could take over the factory Javelins for 1970. According to Donohue, “Since we hadn’t broken off with Chevrolet yet, I felt a little out of place—as if we were cheating on our wives or something—although it was really a legitimate business meeting. Roger was being almost too honest with them about our position. He came right out and said we needed exactly ‘so many’ dollars to run the Javelins for a season. McNealy said it was about the range they had expected, and we got into negotiations over terms and bonuses. Roger was so mad at Chevrolet at that point that he said that he wasn’t interested in any bonus dollars in the contract for 2nd in the championship—it was going to be 1st or nothing.”

After the deal was struck, a press launch was held in Los Angeles to announce that Penske Racing would be fielding a pair of AMC Javelin AMX’s for drivers Mark Donohue and Peter Revson in the 1970 Trans-Am championship. McNealy stated to the press, “In 1970, the Trans-Am is where it’s going to happen. There is going to be a hand-to-hand struggle among the behemoths of Detroit and we intend to be right in the middle of it. That’s the primary reason that we approached Roger Penske to take over our program. Roger and his team are proven winners and they will ensure that we have the most competitive program possible.” For his part, Penske got up and proceeded to tell the assembled press that the Penske Javelins would win seven races in their first year. If Donohue looked a little sick after the press conference it was probably with good reason, as he and the team hadn’t so much as laid eyes on the Javelins that they would be taking over, yet his boss had just written a very big check that he and the rest of the team were going to have to honor!

Ironically, their plight seemed even more dire after the team took possession of the Javelin racecars and equipment used by the Kaplan team in 1969. According to Donohue, “Compared to what we were used to, it was the sorriest mess I’ve ever seen…We sold most of the stuff, but kept one car to use as a reference for a while.” Initially, testing of the Kaplan car driven by Ron Grable and Jerry Grant the previous year demonstrated severe suspension and handling problems partly caused by the fact that the racecar was being run so low to the ground that there was literally no suspension travel left—the car rode on the bump stops like a 3,200-lb go-cart. With only six months remaining before the start of the 1970 season at Laguna Seca, Donohue and the Penske team quickly came to the conclusion that the Kaplan cars had too many problems and that they would be better off building a brand new racecar from scratch. As a way of achieving this, Penske lured engineer Don Cox away from Chevrolet to come head up Penske Racing’s Javelin program. Cox had not only been instrumental in engineering Penske’s championship-winning Camaro program the previous year, but he had also worked extensively with Jim Hall on the Chaparrals, as well.

Photo: Casey Annis

Cox and Donohue set to work on a stripped body shell delivered from the AMC assembly line in the late fall of ’69. Cox worked from November 1969 to February 1970 on designing a totally new front suspension for the Javelin; this included new spindles, A-arms, uprights and hubs. After testing the Kaplan car, Donohue determined that the Javelin suspension not only lacked adjustability, but that it also suffered from weakness and flexing. As a result, Cox’s new suspension was dramatically stiffened with a custom spindle and upright arrangement that would allow the team to lower the ride height, without sacrificing suspension travel.

At the rear end, Donohue initially thought that the Javelin would benefit from some negative camber. In order to achieve this, the team experimented with what they called a “gronked” rear end, which was a live axle that had been bent upwards slightly, and had its bearings pressed in at a slight angle to offset the bend. This “Unfair Advantage” was both expensive and technically difficult to pull off, which made it a big disappointment to Donohue when, in back to back tests, it didn’t prove to be any faster than the standard rear end. Donohue later chalked this result up to the fact that the car’s heavy weight (as compared to a Formula car) maximized its tire contact patch at the back, regardless of camber. As a result the “gronked” axle was never used in competition.

In addition to the suspension re-design, the Javelin also required extensive development of other areas including the brakes, aerodynamics and engine. Like most big-bore Trans-Am cars of the period, the Javelin was woefully under-braked for its high-speed, 3,200-lb mass. Donohue had initially chosen to equip the Javelin with the latest Kelsey-Hayes brakes, as were being used on the Mustangs. However, the Penske team had to contractually wait until the Bud Moore team was finished testing Kelsey-Hayes’ newest trick setup. After two months of waiting, Donohue couldn’t afford to wait any longer and so opted to go with Girling disc brakes on all four corners for ease of interchangeability. However, having the same calipers all the way around created the problem of an imbalance from front to rear, so Donohue and the Penske team installed an inline vacuum-assisted booster on the front circuit that doubled the pressure and made for near-perfect brake balance.

Photo: Casey Annis

Aerodynamically, Donohue and Cox determined that the Javelin needed a much larger rear spoiler. However, the only way that they could run one was if it was homologated on AMC’s street Javelin AMX. So Donohue went to AMC and begged them to build a special run of street Javelins. The response from AMC was initially negative, but Donohue persisted, insisting that the program would not be competitive without it. In the end, AMC agreed, but only if Donohue would lend his name to the special street version. As a result, 2,500 examples of the Mark Donohue signature Javelin were produced with tall rear deck-spoilers, and engines that now featured four-bolt mains and open port heads.

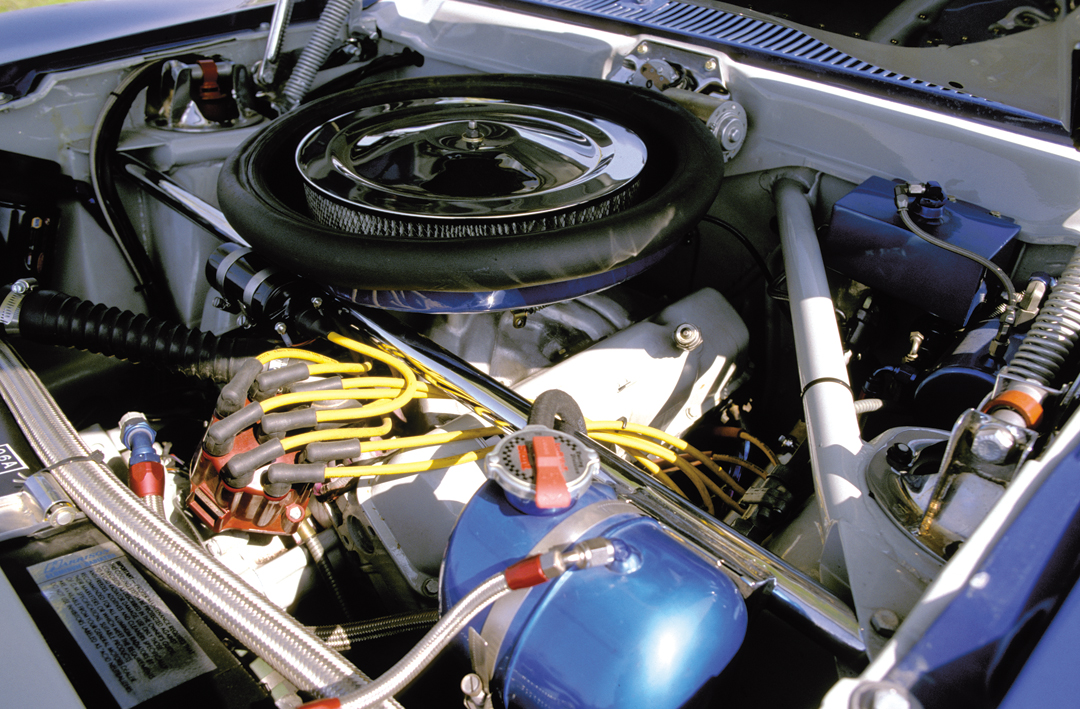

The AMC 305-cu.in. V-8 engine, which was created by de-stroking the AMC 401 V-8, was another problem area for the Penske team. Not only had the engines been unreliable during the 1969 season, but they were also down on power by a good 100 horses, compared to the 475 horsepower Chevrolet engines that Donohue was used to. The Penske Javelin engine program was given to Traco, in Southern California, while Penske hired the original designer of the AMC V-8, Dave Potter, to consult on the project. The Traco-built motors were putting out about 375 horsepower in early 1970, but the car’s first outings began to highlight a fundamental problem that would plague them throughout the early part of the 1970 season.

The Penske Javelin made its debut at the 1970 24-Hours of Daytona, where there was a special class for Trans-Am cars. Donohue co-drove with Peter Revson and led the class until Lap 205, when they lost a connecting rod. Little was made of this until the team showed up at Laguna Seca in April for testing prior to the season opening Trans-Am race. During the test, the team lost three more motors, quite unexpectedly. What the team had not accounted for was that they had so improved the suspension and braking capabilities—and thus the cornering abilities of the Javelin—that now it was pulling higher g-forces in the corners, which was temporarily starving the oil pump. Several solutions involving elaborate windage trays and the like were tried, but the problem was not completely solved until Penske discovered that the Bud Moore Mustangs were running with a “stacked” dual oil pump arrangement that, while not meeting the intention of the rules, was technically legal. Apparently, Penske was not the only one who could benefit from an “Unfair Advantage.” Fortunately for the Penske team, once this dual pump arrangement was installed in the Javelin, the oil starvation problem was permanently cured.

Photo: Cheryl A. Jones

As a result of the oil starvation problem and being down on horsepower to the Mustangs, after the first four races of the 1970 season, Donohue and Revson had garnered a pair of 2nd and 3rd place finishes each, but nothing close to the seven victories promised by Roger Penske. However, rain at the Brainerd event helped normalize the horsepower disparity between the Javelins and the Mustangs, allowing Donohue to score the first Javelin Trans-Am victory. And not a moment too soon, as Bill McNealy later informed Penske and Donohue that he had planned to terminate their contract after Brainerd, but as they had just won the race, it no longer seemed like a good idea!

With the oil starvation problem solved, and stronger and stronger Traco motors coming down the pipe, Donohue was able to go on to score further victories at Elkhart Lake and St. Jovite, as well as 2nd place finishes at Watkins Glen and Kent, Washington, but it was too late to stop Parnelli Jones and the Bud Moore Mustangs from winning the 1970 championship. Penske had not been able to make good on his pre-season promise of seven victories, but the 1971 season would be an entirely different story.

The Lone Javelin

Development work on the Javelin continued into the 1971 season. Among the many improvements were newly homologated body changes including a flush-mount grille, reverse-facing hood scoop and an aerodynamically improved front valence. The team also opted to put all its efforts into a one-car effort for Donohue, resulting in Revson’s departure from the Penske Trans-Am program.

Photo: Pete Luongo

Fortunately, the hard work, and hard knocks, of the previous year paid off with Donohue winning the season-opening event at Lime Rock, over the Mustang of Tony DeLorenzo. Donohue and the Javelin faltered soon thereafter at Bryar, New Hampshire, when a carburetor float became stuck, but came right back with a 2nd behind the Mustang of George Follmer at Mid-Ohio. What followed was an unprecedented string of six consecutive victories at Edmonton, Brainerd, Elkhart Lake, St. Jovite, Watkins Glen and Michigan International. With this remarkable string of wins, Donohue clinched the 1971 Trans-Am championship for himself and Javelin quite early in the season. In fact, at the season-ending Riverside race, Donohue turned the car over to Jackie Oliver, who finished a creditable 3rd behind the Javelins of George Follmer and Vic Elford. Sadly, while the 1971 season marked a great triumph for Donohue and the Penske team, it also brought a close to the final chapter of the great pony car wars. Ford and Chevrolet had, by this time, pulled their massive factory support out of the Trans-Am, leaving the field to the privateers. In the case of the Penske team, part way through the 1971 season they were offered the factory Porsche 917 Can-Am program. As a result, Penske sold the Javelin program on at the end of the 1971 season and refocused all of the team’s efforts on the 1972 Can-Am season. However, this by no means spelled the end of the Penske Javelin’s useful racing life.

Donohue’s championship-winning Javelin was purchased by Bill Collins, who campaigned the car in the 1972 Trans-Am championship. Collins scored five top-10 finishes in the car, including a 2nd place at Sanair, Canada and a 3rd at Road America. At the end of the 1972 season, Collins then sold the car on to Jocko Maggiacomo, who raced the car several times in the 1973 season but with no notable results. Maggiacomo raced the Javelin only twice in the 1974 season but was able to finish 6th at Lime Rock and an impressive 2nd at Pocono behind the Corvette of John Greenwood. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Maggiacomo parked the car for the 1975 Trans-Am season, but then brought it back out for a full campaign in 1976. Running in the Over 5-liter class, Maggiacomo scored 1st place finishes at Pocono and Nelson Ledges, as well as a pair of 2nd place finishes at Elkhart Lake and Mosport. These results, combined with other top five finishes that season, enabled Maggiacomo to win the 1976 Trans-Am Over 5-liter championship. Perhaps even more impressive is the fact that this Javelin is the only single chassis to have won more than one Trans-Am championship—and those were separated by five years, no less!

Driving the Javelin

Photo: Pete Luongo

After the 1976 championship, Maggiacomo sold the car to George Boyd, who placed the car in the proverbial barn until it was unearthed and purchased by Jamey Mazzotta in 2002. Mazzotta entrusted the restoration of the car to Mike Eisenberg and MAECO Motorsport in Southern California, who painstakingly restored the car back to its 1971 championship form.

Sitting in the paddock at Central California’s Buttonwillow Raceway, the ex-Donohue Javelin looked almost sinister to me—downright primordial in fact. There’s something about the shape of those long front fenders that evoke for me images of a giant, menacing undersea creature—like some freakish, mutant manta ray. Whether you like the styling of the 1971 Javelin or not, you have to tip your hat to the fact that this is one stunning example. The attention to detail, which the Penske team is so famous for, is evident, and Eisenberg and his team have done a fantastic job of bringing it back to its former glory.

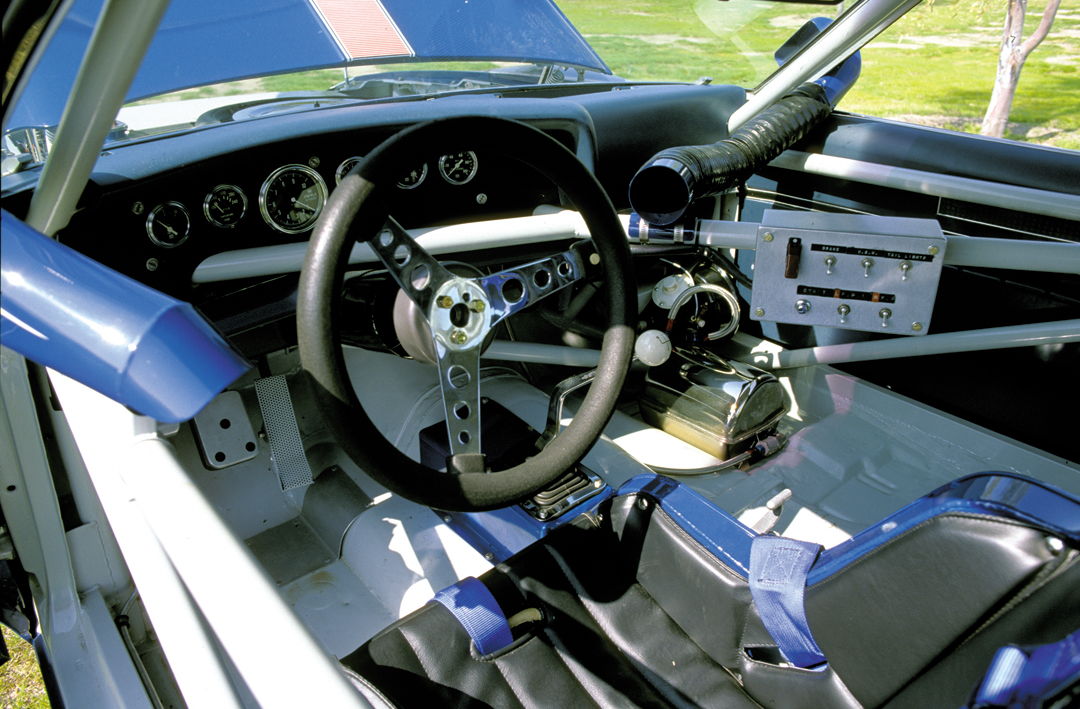

After getting suited up, I clamber into the cockpit—which is something of an exercise even a contortionist would find challenging. Eisenberg, who is an expert in restoring and maintaining historic Trans-Am cars, tells me that this example has about the most extensively triangulated roll cage of any that he’s ever seen on a Trans-Am car. In essence, Donohue and company built a tub-frame chassis within the confines of the Javelin bodyshell.

Once nestled inside the cockpit, the Javelin is all business. Stripped and painted gray, the interior boasts only the original dashpad, a couple of vinyl-covered door panels and a small instrument cluster. Really the only two dominant features in the cockpit are the large NASCAR-style three-spoke steering wheel and the large ivory shift knob that adorns the Hurst-style gearshift lever.

After flicking on the main ignition switch and turning on the dual fuel pumps (located on either side of the tank for maximal scavenging), I pause for a moment as my finger hangs over the starter button. Deep cleansing breath…and push…a brief shiver goes through the car before it absolutely explodes to life. To say that the Javelin is loud is to say that a hurricane is a gentle breeze. With a pair of sewer pipes dumping exhaust out under either door, the Javelin rumbles like a big-bore Can-Am car. In fact, I had to stop to verify that I had actually put in my earplugs, as it was that loud. A glorious noise mind you, but deafening.

Once the Javelin’s warmed up, I’m in for a surprise when I go to put her in gear. Due to the position of the seat relative to the left front fender well, the pedals are dramatically offset to the left. Matters are made even worse by the fact that the car not only features a huge brake and gas pedal, but a tiny clutch pedal, which is located very high up in the footwell. If you weren’t paying attention and put your foot straight in for the clutch, you’d catch the brake instead—that could make for some interesting moments!

So, being six feet, with long legs, I literally have to push my leg around the big NASCAR steering wheel and then lift it up to the clutch pedal! With this done, I depress the clutch, select first in the agrarian-feeling T-10 top loader and slowly pull out onto the pitlane.

Around the pitlane, and at low speed, the Javelin’s steering is an armful (no wonder it has such a big diameter wheel—you need the leverage!). But once up to speed the entire character of the car changes. This car has a sharpness—a precision—that is completely belied by its big, ungainly appearance. On the track the car feels so taut and precise that it is as if it was machined out of a solid billet of steel. Straight-line acceleration is of the “peel your eyelids back” variety that one would expect from a Trans-Am car, but the real surprise here is the handling and brakes. This car does not feel like a Trans-Am car. The turn-in and handling response is so good it really feels more like a heavy Formula car, like a F5000.

Like most big-bore sedans, the Javelin likes to be steered with the throttle. Get your braking done in a straight-line, start your turn in for the apex, then feed in the throttle and control the car into, and out of, the apex by modulating the loud pedal. Pounding around the Buttonwillow track with greater and greater speed this way, the Javelin absolutely comes alive. Powersliding the car out of the turns is an immensely satisfying experience, but I’m also cognizant of a certain “nervous energy” in the car that provides a not so subtle reminder that it could very well bite you if you’re not careful. Two laps later, I enjoyed a practical demonstration of this phenomena.

As I become more comfortable with the car, I am able to carry more and more speed down Buttonwillow’s West Loop straight, before braking hard for the decreasing radius hairpin at the end. On the lap in question, I take her a little deeper, get on the brakes hard (they really are amazingly good), downshift to third with a satisfying blip of the throttle and then grab second and slowly start to let out the clutch. However, as I do this the rear wheels are passing over a washboard section of the track and the combination of the braking, weight transfer and uneven surface start the rear axle to hop. I feel the axle hop once, twice, and then get that “Oh shit” sensation in the seat of my pants as I start to feel the back end come around towards the outside. Interestingly, the way it happened felt surprisingly predictable—in fact, I started to feed in more gas to counteract the slide—but what with discretion being the better part of valor, and this being someone else’s half-million dollar racecar, I thought it more prudent to drop the clutch, stand on the brakes and get things stopped, rather than risk it. In the end, the experience amounted to nothing more than just a lazy quarter loop—no touch, no harm, no foul—but it definitely underscored what many people have said about ex-Donohue cars; that he liked them nervous and a bit twitchy. With that said, this is still one hell of a fine racecar, and really a testament to both Donohue’s and the Penske team’s ability to turn almost anything into a competitive racecar. Just imagine what they might have done with the Pacer.

Buying a Javelin

While a number of different Javelins were raced by privateers and other teams in the Trans-Am series, the Penske cars truly rise to the top of the heap, with this championship-winning example at the very pinnacle. Cars driven by one of the lesser independents can range in value from $100,000–$200,000, with some of the better team cars selling for on-upwards of $350,000. However, this championship-winning car recently sold for $450,000, indicating just how much history, and the Penske touch, add to the value of what is essentially—let’s be honest—a fairly mundane American sedan.

Specifications

Bodywork: Steel unibody with fully triangulated roll cage.

Wheelbase: 110.5″

Track: 74″

Weight: 3,200-lb

Suspension: Front: Custom uprights with reinforced control arms, tubular splined sway bar and double-adjustable Koni shocks. Rear: Live axle, leaf springs, Panhard rod.

Engine: 305-cu.in. V-8

Induction: Holley 750 cfm 4-barrel carburetor on Edelbrock “Torquer” manifold

Valvetrain: 2 valves per cylinder

Horsepower: 450 hp @ 6,800 rpm, 405 ft.lb. @ 4,800 rpm

Gearbox: Borg Warner T-10 four-speed

Wheels: 8″ x 15″ Minilites

Resources

Donohue, M., Van Valkenburgh, P.

The Unfair Advantage

Bentley Publishers, Cambridge, MA, 2000

ISBN 0-8376-0069-3

Friedman, D.

Trans-Am: The Pony Car Wars 1966–1972

MBI Publishing, Osceola, WI, 2001

ISBN 0-7603-0943-4

Sincere thanks to Jamey Mazzotta for his kind use of the car and to Mike Eisenberg and the crew at MAECO Motorsports for their generous assistance.