1957 Aston Martin DBR1

Aston Martin’s relationship with the 24 Hours of Le Mans goes all the way back to 1928 when Jack Bezzant/Cyril Paul and “Bert” Bertelli/George Eyston launched the British company’s assault on the event with LM2 and LM1, Aston’s 1495-cc, 4-cylinder racer. Neither car made it to the finish, but the effort marked the beginning of a quest that goes on at this very moment. Aston Martin is still at Le Mans.

The Astons returned to La Sarthe in 1931, after the Bentley dominance had been taken over by Alfa Romeo. Bertelli, however, was 5th this time and won his class. The cars were at every event in the 1930s, usually finishing well up the field, often winning the 1.5-liter class, and managing 3rd overall on one occasion. Even with that record, however, the big assault was to wait until well after WWII, and though it finally resulted in victory, it had been a very hard road.

Thus, it is a special privilege that Vintage Racecar was able to test the car that finally brought victory to Aston Martin at Le Mans, DBR1/2 which was built in 1957, won the 24 Hours in 1959, and is one of the most significant racecars anywhere, having raced almost nonstop from 1957 to the present day.

The David Brown Astons

As one of the 1959 Le Mans-winning drivers, Roy Salvadori, has said: “The name Aston Martin to me reads John Wyer and David Brown.” In 1946, just after the war had ended, Aston Martin was up for sale and Brown bought it, followed shortly by the purchase of Lagonda and the Tickford coach-building concern. Brown had been in business building tractors with Harry Ferguson, but they fell out, so Brown designed and built his own, selling nearly 8,000 during the war years and becoming a wealthy man. His roots in the tractor business often led to cruel jokes about Aston Martins and their agricultural ancestry!

For his money, David Brown got some old machinery, premises at Feltham in Middlesex, the services of designer Claude Hill, and Hill’s prewar project, the 1936 experimental “Atom,” which would be the precursor to the Aston DB1. He added the Lagonda name to his growing portfolio, along with the rights to a new 2.6-dohc engine, and some prototype cars. Brown had Hill working on development of the now-aging Atom car, and Hill sought agreement to run it at the 1948 Spa 24 Hours. Brown reluctantly agreed, but in the hands of Leslie Johnson and “Jock” Horsfall, the car scored a remarkable win. In practice, the pair had also practiced a hurriedly built new car, later to be named the DB1. The quest was on.

In the years after the Spa victory, David Brown united the Lagonda engine and the chassis that Hill had developed for the Atom. Sadly, this very much upset Hill, who was improving his own engine, and he decided to leave the company. In 1949, two cars were entered at Le Mans in the new DB2 configuration with the Lagonda 2.3 engine, and a further DB2 which had an enlarged unit of 2.6-liters. One of the cars finished 7th, and then the three cars were 3rd, 4th, and 5th at the Spa 24 Hours. Similar results came in 1950, with Lance Macklin and George Abecassis finishing 5th at Le Mans and winning their class. It was the same story in 1952, this time Macklin getting 3rd at Le Mans. The year 1952 also brought the introduction of the new DB3, a “proper” two-seater sports car. The DB3 produced some good results, in spite of reliability problems with water pumps. Then the new recruit to the team, Peter Collins, brought Aston Martin its first overall sports car victory by winning the Goodwood Nine Hours with Pat Griffith. The up-and-coming Collins had rather badgered John Wyer into inviting him to drive in the team. Wyer had been director of the Monaco Garage and prepared and managed cars at Le Mans for his customers. David Brown was at Le Mans to witness Wyer’s ability as a manager and, in early 1950, Wyer came to Aston Martin to develop and run the competition department. With much more modest resources than Mercedes-Benz, Wyer would rival the German company’s Neubauer as one of the great team managers of all time. Wyer would move up to the post of general manager in late 1956, when Reg Parnell became the racing manager, but Wyer always remained very close to racing.

The Advent of the DBR1

Developments in racing and road cars ran parallel through the 1950s. When the DB3S sports car appeared in May 1953 that is where the works racing effort was focused. Customers were buying DB2s and racing them privately, and the popularity of the roadgoing DB2, DB 2/4 Mk I, II, and III increased, until the new generation DB4 appeared in 1959.

The DB3S provided good results for Aston Martin: seven overall victories in 1953, one in 1954, nine in 1955, and six in 1956. Le Mans, however, remained elusive, and Aston Martin couldn’t get a single car to the finish in ’52, ’53, or ’54, until Peter Collins and Paul Frère brought a DB3S into 2nd in 1955 as the other team cars retired. The 1956 race witnessed Collins, this time with Moss, repeating the 2nd-place result. In that race Tony Brooks and Reg Parnell retired with engine trouble in the team’s new car, the DBR1 with 2493-cc engine, running in the prototype class.

Under Wyer’s supervision, the DBR1 would become the focus of attention for 1957, with the aim of winning at Le Mans. Ted Cutting had been responsible for the design of the DBR1, and though it started with the existing “small” engine, it would soon get the 3-liter unit. It retired at Le Mans in 1956 with the bearings run, but a great deal of work was about to go into the car. It featured a multi-tubular space frame of small diameter, chrome-molybdenum tubing that was substantially lighter than the DB3S. A longer wheelbase and increased track improved the handling. The suspension was pretty much DB3S with trailing links and torsion bars in the front, and a de Dion axle behind the gearbox at the rear, located by Watts linkage and rear torsion bars.

The new car’s engine had the same bore and stroke as the DB3S and a 60-degree twin-plug head, but the camshafts were now gear- rather than chain-driven. There was also a new alloy block, and with triple Weber 45 DCO carburetors, the power was up to 260 bhp at 6,250 rpm.

Cutting worked to create a better handling package in the DBR1 by locating the engine and gearbox very carefully in order to balance the car. The DBR1 had the new David Brown gearbox CG537 as part of the design. However, it was, or was often said to be, the car’s Achilles’ Heel. Many drivers seemed to struggle in the early races when it would either get stuck in gear, or refuse to change down, and gears were frequently heard to be grating and crashing. There are mixed opinions on this. John Pearson, usually a Jaguar man, looked after “our car,” when it was owned by David Ham in the 1960s and said it was simply a matter of knowing where the gears were and sliding into gear. I had the chance to get a view on it from another old friend, Rex Woodgate.

Rex started as an Aston Martin mechanic in 1957, first doing chassis work and then moving to gearboxes and back axles. He had daily contact with John Wyer, though he admits, “Most of the time I was trying to hide from him!” On the subject of gearboxes, Rex recalled:

“When the DBR gearboxes first came down from the factory, I suggested one or two improvements, which I thought would happen, but they didn’t, and the early problems were a result of this. The David Brown boxes were built up in Huddersfield, and I was sent up to bring them down to Feltham and work on them. At Huddersfield, they were mainly making gearboxes for trucks and such, and they didn’t really have the understanding of quick-change racing boxes, though in my workshop we eventually sorted out the problems. It was basically a very good transaxle, and very versatile, but was somewhat complex with spur wheels on the top of the differential. Stirling Moss was very good at getting the most out of what we could do with the box, but he wasn’t always listened to, and there were limits to what I was allowed to do.”

Tim Samways, who has looked after the car you see here since 1992, has done a great deal of work on developing the car—and most of the other surviving DBRs as well. He recalls that the gear change was originally the opposite way round, and could select two gears at once. His solution was to put new internals into the gearbox, which the other DBRs now use as well.

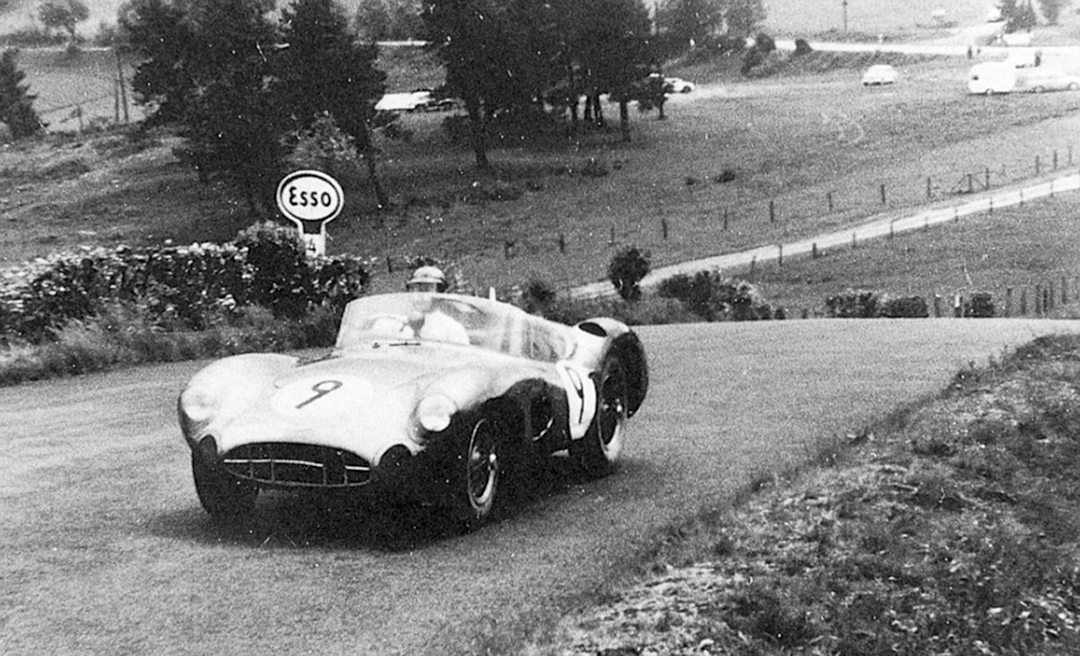

DBRs Go Racing…the Story of DBR1/2

At the beginning of 1957, only DBR1/1, still with the 2.5-liter engine, was ready, but it finished 2nd to Scott-Brown’s “sprint” Lister Jaguar at Oulton Park. This car was joined at Goodwood two weeks later by a works DB3S with a new 3-liter engine, and the two Astons were 2nd and 3rd behind Scott-Brown. Then at Spa in May, DBR1/1 and “our car” DBR1/2 appeared together for the first time, both with the new 2,922-cc engine in place. Tony Brooks, absolutely in his element in the fast sweeps of the Spa circuit, gave DBR1/2 a superb debut victory, with Salvadori 2nd in DBR1/1.

The Nürburgring 1,000 Kilometers was the first really important event for Astons in 1957, and Wyer sent DBR1/1 for Salvadori/Les Leston and DBR1/2 for Brooks and young Noel Cunningham-Reid. There were also two DB3S cars, one with the larger engine, as the DB3S was being used as a rolling test-bed for developments for the DBR1s.

The Aston team faced formidable opposition from Maserati, Ferrari, and Jaguar, but Tony Brooks was the star of practice, and the race, setting fastest time on Thursday and running 2nd only to Fangio on Friday. Brooks took the initial lead, but was passed by Moss in the Maserati 450S until that lost a wheel. Brooks found himself back in front, and when he handed over to Cunningham-Reid, they held the place right to the end. Thus, DBR1/2 took its second win, leading home Collins and Gendebien in a 4.1 Ferrari, Hawthorn and Trintignant in a 3.8 Ferrari, with a Maserati 300S that Fangio and Moss had taken over finishing 5th.

The next race in 1957 was at Le Mans. Astons had been developing a new car, the DBR2, which would feature a larger 3,670-cc engine. This car was intended originally for shorter British sprint races, but it would see wider service. For Le Mans, DBR1/1 would again be driven by Salvadori/Leston, DBR1/2 by Brooks/Cunningham-Reid, and DBR2/1 would go to the Whitehead brothers. Works-supported private Jaguar D-Types benefitted from all the mechanical disasters at Ferrari, Maserati, and Aston Martin. Brooks was in 2nd at 2:00 a.m. when the car, jammed in 4th gear, got away from him and crashed, injuring him quite badly. The other DBR1 also had its gearbox break, and the DBR2, down on power, pumped out all its gearbox oil. Brooks would, however, recover sufficiently to take the famous shared British GP win with Moss in the Vanwall at Aintree in July.

While Roy Salvadori took a 2nd in DBR1/1 at Silverstone, the cars didn’t come out again until the 3-hour race at Spa late in August, where the drivers were mostly in their usual cars. Brooks in DBR1/2 had the new 95-degree head, while DBR2/1 was in the hands of Cunningham-Reid, who crashed in practice, and though unhurt, the car was out. Brooks held the lead throughout, gaining yet another win for DBR1/2, leading home two Ferraris and Salvadori—again stuck in 4th. At the Silverstone International Trophy in September, the sports car race saw Roy in the new DBR2/2, Brooks in DBR1/2, Cunningham-Reid in DBR2/1, and new boy Stuart Lewis-Evans in DBR1/1. Scott-Brown got the Lister-Jaguar in front, but Roy fought back to win the fastest British sports car race ever. Cunningham-Reid was 3rd, Brooks 4th, and Lewis-Evans 6th, Roy finding the new DBR2 better in both handling and gearbox departments. He would later admit he was by then being more careful about how he changed gears.

1958

Astons built a new DBR1/3 for 1958 and all three would do Nürburgring, Le Mans, and the Goodwood Tourist Trophy, while the new car would do the Targa Florio and the other two would go to Sebring. With the Sports Car World Championship now running to a 3-liter limit, Aston Martin and Ferrari were the main contenders as Maserati had withdrawn, although Porsche was now in the picture as well.

At the Sebring 12 Hours, Moss was back on the team, sharing DBR1/2 with Brooks, while Salvadori was sharing with his new partner, Carroll Shelby. Opposition would come from Ferrari and Cunningham-entered Lister-Jaguars with a smaller engine. The DBR1s all had the 95-degree head, 7-bearing crankshaft, and Weber 50 DCO carbs. Moss and Brooks led from the start and were in front when Salvadori/Shelby retired with a sheared front crossmember. Then DBR1/2 lost time with the gears sticking! Moss then set out in a brilliant chase to catch the Ferrari of Phil Hill and Peter Collins. He got within 15 seconds of them before the gearbox gave up for good.

The DBR2s then did well in a number of British races, where a new DBR3 appeared. This was a DBR1 chassis with a 2,922-cc engine, though this unit was a DB4 engine to very different specs, with 6 Weber carbs. Then Moss and Brooks took DBR1/3 to the Targa Florio with a DBR2 training car. After another amazing drive, Moss was off the road, had a broken crankshaft damper, and then the gearbox went again. Then the DBR2s went to the non-championship race at Spa, where Archie Scott-Brown was killed. The DBR2s were then sent on loan to the United States where they were raced by privateers.

At the Nürburgring 1,000-Kilometers, all three DBR1s were out again. Moss was again the star, sharing with Jack Brabham, who was not all that comfortable in a front-engine sports car. Salvadori/Shelby retired DBR1/1 at the end of lap two, stuck in top gear, and Brooks/Lewis-Evans retired in a ditch near the end after a good showing, but it was all Moss in DBR1/3 fighting off the Ferraris to win. Then came Le Mans, where expectations were high. However, Moss and Brabham had the engine go at 30 laps, and at four hours, Lewis-Evans had a collision and limped back to retire, while Brooks/Trintignant held 4th in DBR1/2. That car moved up to 3rd, but Trintignant had the gearbox fail at 6:00 a.m. and Ferrari won.

Although Ferrari had clinched the Sports Car World Championship, three DBR1s came to Goodwood for the Tourist Trophy, and Moss and Brooks, in DBR1/2, essentially led the whole way, with Salvadori/Brabham 2nd in DBR1/1 and Shelby/Lewis-Evans 3rd in DBR1/3. The opposition wasn’t spectacular, but it was a good show on home ground. DBR1/2 had thus scored its 4th significant win.

1959…the Big Year

At the beginning of the year, the priorities were clear: Formula One and Le Mans. In retrospect, we can see how those priorities were a bit ill-judged. First, it should have been clear that a front-engine Grand Prix car was unlikely to be the way to go, and that early plans to do only Le Mans with the sports cars might also go awry.

The Sebring organizers convinced John Wyer to send DBR1/1 to Florida for Salvadori and Shelby, but that ended in disaster as the gear lever broke off at 32 laps. By now, privateer Graham Whitehead had a new car, DBR1/5, a private effort with works backing. Again, Wyer relented when the BRDC asked him to send a car for the International Trophy meeting. Moss drove DBR1/2, and he finished 2nd. Moss then pressed Wyer for a car for the ’Ring 1,000-kilometers, and he agreed—though Moss had to pay the expenses. DBR1/1 was sent and Moss, with Jack Fairman, put it way out in front. Fairman dropped it into a ditch, and after a titanic struggle, wrestled it out. When Moss got in, they were well behind the Ferraris. At the finish, they were well in front. That was Moss.

Then came Le Mans

A lot of work was done making the bodywork more aerodynamic and efficient, with spats over the rear wheels and partially covered fronts. There were cooling ducts and a new, longer exhaust. The DBR3 now reverted to being DBR1/4 and was to be driven by Trintignant/Frère. Moss and Fairman would drive DBR1/3 with a four-bearing engine and 255 bhp; Salvadori and Shelby would have “our” DBR1/2 with seven-bearing engine and 244 bhp. Whitehead brought his DBR1/5 for himself and Brian Naylor. This was a serious effort.

Wyer’s intention was to send Moss out to wear out the opposition, mainly Ferrari TRs. There were D-types but the 3-liter Jag engine wasn’t that quick. Moss/Fairman and the Behra/Gurney Ferrari fought for the lead in the first three hours. Moss was stopped by a broken valve head, but the Ferrari also slowed with overheating. Salvadori and Shelby, who had resolved to go easy on the engine and gearbox, eased into the lead ahead of two more Ferraris.

In the night, DBR1/2 lost time when Roy stopped to investigate a vibration he thought was the gearbox. This turned out to be a damaged tire, so Roy and Carroll had to make up lost distance while still trying to preserve the car. They were back up to 2nd in the morning when the leading Ferrari went out, and then ran cautiously on to Aston Martin’s finest win. Trintignant and Frère brought DBR1/4 into 2nd place as well.

To rub it in, DBR1/2 had its sixth and final significant win later in 1959, taking the Tourist Trophy yet again, this time in the hands of Shelby and Fairman, with some help from Moss. This was in spite of the pit fire that tried to destroy the team and injured John Wyer. The Sports Car World Championship now belonged to Aston Martin after years of trying. Subsequently, David Brown announced the team’s retirement from sports car racing.

Driving the Le Mans Winner

Most of the DBR1s were sold to private teams and indeed did some important races over the next two years. DBR1/2 went to Major Ian Baillie and he and Edward Greenall were 5th at the 1960 ’Ring 1,000 race, and 9th at Le Mans with Fairman co-driving. The car changed hands and David Ham raced it in the early ’60s when John Pearson looked after it. Then it went to Neil Corner and Chris Stewart who continued in historic races through the 1970s. It was in the Jack Setton Collection for some time before it went to the current owner, and has been regularly raced successfully since the early 1990s by Peter Hardman. It has been restored and cared for over many years by Tim Samways.

It was Samways who brought the car, freshly assembled for its 50-year Le Mans anniversary, to the Goodwood Press Day. Peter Hardman was to drive it on the Goodwood hill, and Samways put me in the passenger seat to see how it should be “done properly.” DBR1/2 has done at least 50 races since it has been in the hands of the current owner. This includes Moss’ now famous drive at Monterey a few years ago where he had an uncharacteristic “altercation.” Despite this, the car has always been reliable, finishing 95% of the historic events it has done. It came close to winning the British historic sports car championship twice in the mid-1990s and Moss drove it to 6th at the first Goodwood Revival. Hardman, who is the master of getting everything out of this car, wasted no time after telling me where to hang on.

The revs went up, the noise erupted from the exhaust, and the metallic green machine burst off the line down to the first right-hander. In 3rd gear, he flicked the tail out and held it out, and DBR1/2 shot straight past Goodwood House. With all that torque, he could use 3rd gear around the tricky left that leads up the hill, again with tail out. I was getting the absolute firsthand account of what this venerable machine could do using all of its qualities.

To get the best out of these cars, you need to be able to, as Hardman says, “drift them a bit,” but I was very aware of what everyone says about the foibles of the gearbox. However, I followed my instructor’s advice about getting the revs just right and then slot into gear when they are right—not easy with straight-cut gears. I opted for getting it right rather than learning to drift but, once settled in, I was surprised that everything happens in a civilized manner. First gear has a spring gate that needs to be opened, and that keeps you from selecting first by accident. Though the rev counter reads to 8,000, it was red-lined at 7,000, and we were using about 6,500 at the most. The torque at those revs—in any gear—is massively impressive.

The cockpit is roomy, with two seats installed, has minimum instrumentation, retains all its long distance light switches, etc., and just oozes a feeling of being a wonderful car. Our plan was to have an easy run or two and then a quicker blast, and DBR1/2 behaved impeccably throughout. It was hard to stay focused. This is such an aesthetically stunning car, you want to look at it even while driving. I had to conclude, when I got around to pushing it a bit, that the gearbox seemed fine, if not easy. It was indeed a question of feel and timing. The handling, though you may see me in the accompanying photos with a wheel on the grass, was rewarding—it did what you wanted it to, no problems, no surprises. I will line up for drifting lessons as soon as possible!

Having mastered getting down through the gears without forcing it, I used second at the left-hander where you head up the hill. The sound explodes from the exhaust, and as I whistled past that daunting looking pebbled wall in third, then fifth, the torque took over and propelled DBR1/2 upward. On nearly full power, steering is “easy” with the throttle, and minor corrections with the wheel. I was amazed at the amount of feel that comes directly into the seat of the pants; the front moves a bit, the rear hangs out and a dab of throttle changes the balance. You can almost drive it by the sound it makes, such is the visceral feedback.

Halfway up the uphill pit, the speed is impressive, and I ease back because of the number of trees on each side! Cheering marshals encourage a final hard throttle pedal in top, to the top, and then it neatly bangs back down through the gears as we back off for the collecting area. DBR1/2 behaves superbly, makes you feel in control, and makes you understand why Moss, Salvadori, Brooks, Shelby and the others so much enjoyed racing them. I guess it isn’t surprising that each of these drivers had some of their very best races in this car.

What else can you say—without two volumes—about driving one of the world’s best-known, most successful, and most admired racing cars. DBR1/2 is beyond iconic!

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Multitubular space frame constructed from chrome-molybdenum tubing

Engine: 6-cylinder dohc camshaft, 2922 cc; triple Weber twin-choke 45 DCO carbs, 2-plugs per cylinder

Power: 240 bhp @ 6,250 rpm (originally)

Bore and stroke: 83 x 90 mm

Compression ratio: 9 : 1

Gearbox: David Brown CG537 5-speed non-synchro in unit with final drive

Clutch: 7½-inch triple-plate

Suspension: Front: Independent with trailing links and torsion bars; Rear: De Dion axle, trailing links, and transverse torsion bars

Steering: Rack and pinion

Brakes: Girling single caliper, nonservo disc

Wheels: Borrani 16” center lock-wire type, with 6.00 x 16” tires front and 6.50 x 16” rear

Weight: 15.75 cwt dry

RESOURCES

We owe a great thank you to Harry Leventis, Tim Samways (www.timsamways.co.uk), Peter Hardman, Rex Woodgate…and to Lord March for the freedom to play in his garden! I have known Rex Woodgate for over 50 years, and was fortunate to know John Wyer and Dudley Coram…it has been very special to do this test.

Coram, D. Aston Martin—The Story of a Sports Car. Motor Racing Publications. London, 1966.

Pritchard, A. Aston Martin—The Post-War Competition Cars. Aston Publications. Bucks, UK, 1991.