Ex-Coppa Florio 1907 Wolsit Factory Racer

A little-known aspect of the history of the British Wolseley firm was its Italian connection—a joint venture with the Banca di Legnano and the Macchi di Varese—in the formation of a new Italian company called Wolseley Italiana SA in 1907. The trade name of the new company was “Wolsit.” The objectives of the company were first, the manufacture of cars and trucks and second, the acquisition of concession rights from Wolseley in England. One of the new company’s directors was

J. D. Siddeley, who was then the general manager of Wolseley. He had replaced Herbert Austin in 1905 and his vertical engine designs had been adopted by Wolseley that year, in place of Austin’s favored horizontal engines in the company’s new range of cars. Between 1905 and the end of 1909, the cars made at the Wolseley factory were known as Wolseley-Siddeleys although they were often just called Siddeleys to the dismay of some Wolseley directors.

Wolseley had ceased racing on the Continent after the 1905 Gordon Bennett race in the Auvergne in France because of the prohibitive costs. However, a team of “Siddeley” cars participated in the 1906 TT race on the Isle of Man. Mark Wild was the mechanic on one of those cars, while Arthur George, a former professional cyclist, had driven an Argyll car to 2nd place in the TT, only to be disqualified later for the car being underweight.

On July 1, 1907, an internal order was issued by the board of the Wolseley Tool and Motor Car Company Limited of Birmingham, England for three racing cars to be built to take part in the Coppa Florio race in Brescia, Italy on September 1 of that year. Wolseley recruited Arthur George to drive one of the new Wolsits, while Mark Wild was to handle the second and Jo Durlacher was appointed to drive the third.

Photo: Peter Collins

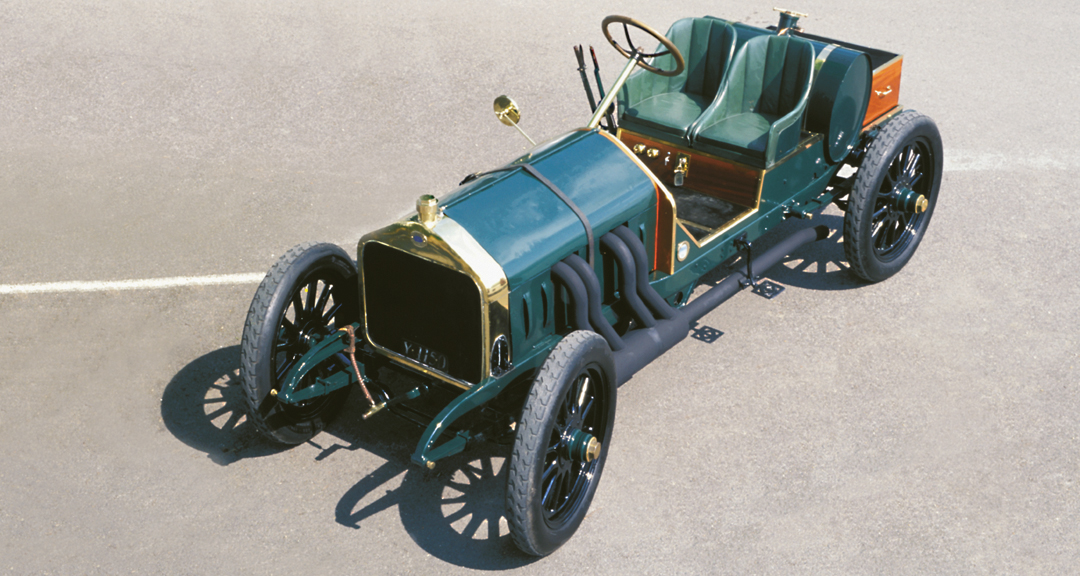

The racing cars were completed in Birmingham and delivered to Italy on August 10, 1907. They had first been taken to Brooklands, tested on the track and then driven in convoy across Europe to Brescia, where the team drivers practiced on the course for the following three weeks. This extremely short time for the construction of three racing cars is a demonstration of the efficiency of the Wolseley factory and of the confidence of the Wolseley directors in the strength and reliability of their products. The cars were entered in the race under the name “Wolsit” to emphasize the Anglo-Italian connection.

The 1907 Coppa Florio was run under the German Kaiserpreis regulations, which had been introduced earlier in the year. The first race was held on the June 14, 1907, on the German Taunus circuit where the 1904 Gordon Bennett race had been held. The prize had been offered by His Imperial Majesty the Kaiser. The regulations were designed to be simple and to encourage the improvement of touring-based cars through racing. The centerpiece of the rules was a maximum engine capacity limit of eight liters. The cars could be two-seaters with racing-style bodies.

Photographs of scrutineering and the weigh-in at the Coppa Florio in 1907 show the Wolsit having different dimensions than some of the other cars. Perhaps it was generally known that the regulations were less rigorously enforced in Italy because the three Wolsit racing cars built in the Wolseley factory in Birmingham did not comply with them! The cars were numbered 5531, 5532 and 5533, although no chassis numbers were allocated to the cars at this stage in their lives. Wolseley must have been sure that the cars would pass scrutiny because the wheelbase was not standard for any model in 1907 and was, therefore, specially chosen for the Coppa Florio race.

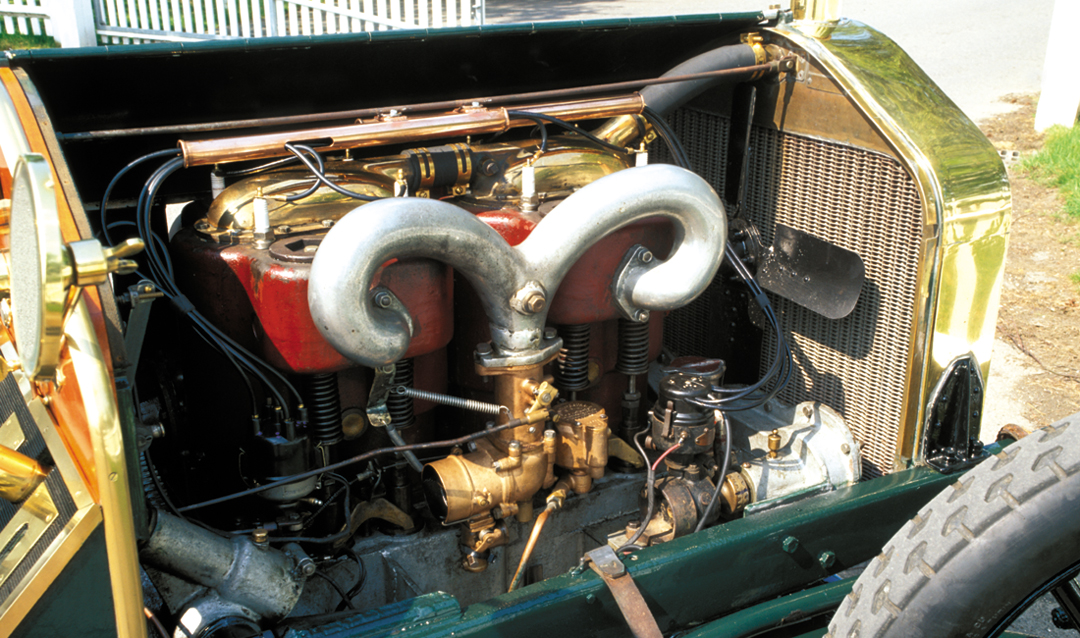

The factory acknowledged that the cars were a combination of parts from various models. One contemporary magazine report (“The Autocar”, September 14, 1907) describes the cars as having modified 45-hp six-cylinder engines but only one car is described as a six-cylinder in its build sheet (5531). Other reports are silent on this point, although one photograph caption mentions that the cars had four-cylinder engines. A photograph of Jo Durlacher’s car shows that it had a six-cylinder engine but it had been entered as “Wolsit 1” and may, therefore, have been car number 5531. If the other two cars had 40-hp four-cylinder engines, this may explain why they were markedly slower than Wolsit 1. However, according to the factory, the “40-hp” engine produced 55 bhp and the “45-hp” engine 58 bhp. The power of the latter engine would have been reduced by the reduction in its capacity to meet the Kaiserpreis maximum of eight liters, so there should have been little difference in performance.

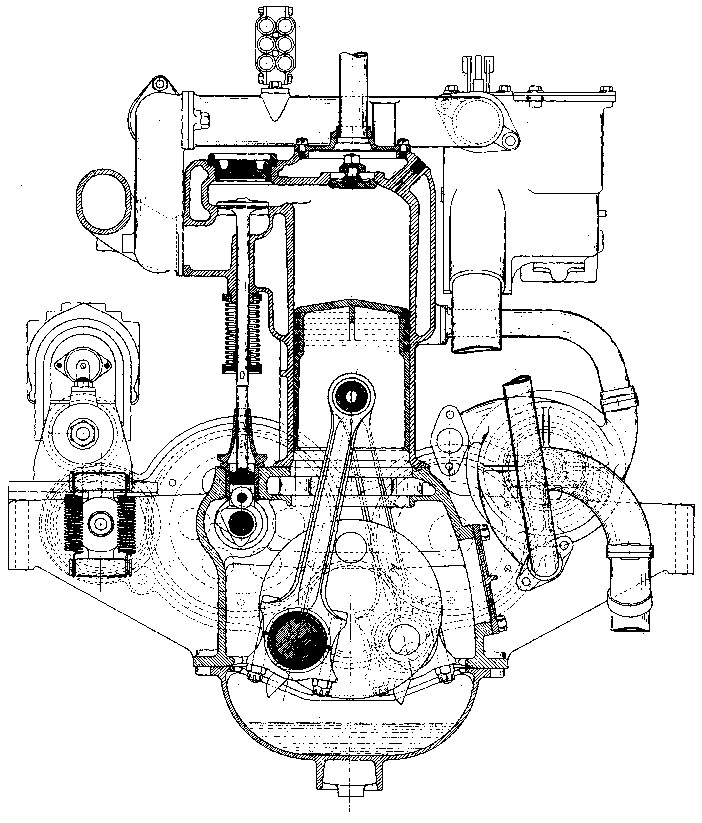

All the racing cars appear to be a combination of the main chassis frame from the 40-hp model and part of the rear chassis frame, the rear axle (live, bevel and with shaft drive) and the four-speed gear box from the 30-hp model. The alterations to the chassis were necessary to accommodate both the large engine at the front and an upsweep at the rear over the live axle. None of the standard 45-hp, 40-hp or 30-hp chassis could be used in unmodified form, the first two because the rear of each of their chassis was flat (both the 45-hp and 40-hp models were chain driven) and the last because there was insufficient room for the engine at the front. So, in fact, these racers were some of the first, true “parts bin specials”!

The 1907 Coppa Florio Race

Less than a week before the race, Wild suffered an unfortunate accident as a result of avoiding some cyclists who crossed the road in front of his car, 5531, and was knocked unconscious for more than three hours. The front and offside of his car were seriously damaged and, while it was repaired in time for the race, he said that “it never answered its helm with absolute accuracy” until it was returned to the factory.

Photo: OwnerÕs Collection

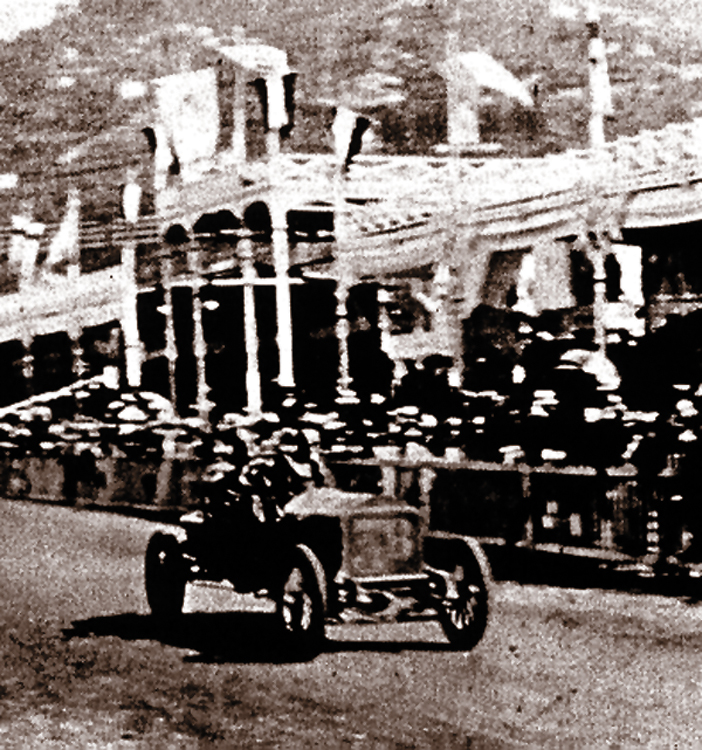

The Coppa Florio race was over a very difficult circuit of 37 miles and lasted eight laps, for a total distance of 301 miles. The course was very flat and was known to be a fast circuit. The surface was partly tarred, although dust was a problem for both the drivers and the cars. On race day, there were 34 starters but only 14 finishers. Eventually, the race was won for Italy by Minoia driving an Isotta-Fraschini in 4 hours, 39 minutes and 53 seconds, at an average speed of over 64.7 mph.

Jo Durlacher only lasted just over a lap, in Wolsit 1, before crashing and landing on a railway line. His was, by far, the fastest Wolsit and he completed the first lap in 10th place, just over three minutes behind Minoia’s leading time. His average speed for the first lap was 60.7 mph. This was a very creditable performance for an untried racing car in a relatively fast race.

Photo: OwnerÕs Collection

George, in Wolsit 3, was nearly eight minutes behind, while Wild, in Wolsit 2 (car 5531), was more than 10 minutes behind Minoia at the end of the first lap. George’s gear change failed on the third lap as a result of grit in the lever mechanism, which was not shielded against dust and dirt. George had established a reputation as an ambitious and persevering driver who did his best to finish a race. His early retirement might indicate that he felt Wolsit 3 was hopelessly outclassed. Wild finished the race in 13th place in Wolsit 2 (race number 3b), which was a brave effort after the damage to his car and himself less than a week earlier. All in all, the speed of the Wolsits in that first race was indicative of their potential, had they been more thoroughly developed.

All three cars returned to Birmingham and were put “in stock” on September 30, 1907. There is no record of any subsequent racing career for any of the three.

History of the 5531

Photo: OwnerÕs Collection

5531 was delivered to a Mr. J. F. Ramsden (John Frescheville Ramsden, the eldest son of Sir John William Ramsden) on June 6, 1908. It was still a racing two-seater painted “Wolseley green picked black.” The wheelbase had been increased to 10-ft, 6-inch, which was not a standard size. The car was altered again in 1912 and was subsequently converted into a shooting brake/game cart. It languished on the family estate of Sir John Ramsden’s daughter-in-law at Biddestone Manor, near Chippenham, Wiltshire, where it was rescued by Arthur Thomas, a well-known Wolseley expert in the late 1970s. It was stored and then purchased by John Brydon with spare parts in 1988. It was later bought by the late Dick Baddiley, who asked Edwardian specialist Richard Black to help him convert it into a racing special by installing a 10-liter Simplex engine. Very little, if anything, was done in altering the chassis. The car was raced and hillclimbed between the late 1990s and 2001 and shortly afterwards went to the present owner. An enormous amount of meticulous research has been carried out in conjunction with the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust at Gaydon using Wolseley records to ascertain that this car is one of the three original Coppa Florio cars, and as such, it currently wears the early registration number of Y1150.

The Simplex engine currently fitted to Y1150 is marginally more powerful than the standard 45-hp capacity of the original 8.7-liter engine before 5531 was sold by the factory in 1908 to Sir John but is also significantly heavier. Sir John bought 5531 with a two-seater racing body. The performance of Y1150 must, therefore, now be very similar to the car purchased by Sir John. The top speed is over 100 mph and the car will cruise for long periods at over 80 mph given suitable road conditions. However, as is the case with almost all Edwardian cars, it only has a pedal-operated transmission brake and a handbrake operating on the rear wheels. There are no front brakes of any kind! This performance must be compared with that of most large-capacity road cars of 1907, which would have had trouble exceeding 50 mph. Smaller cars would have been much slower.

Photo: Peter Collins

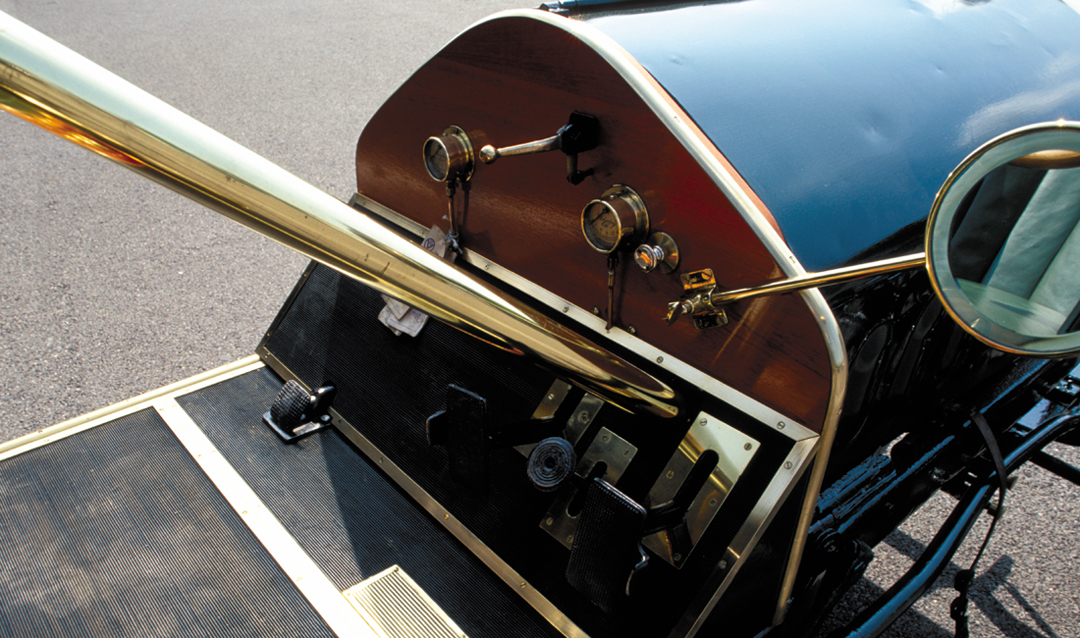

If Y1150 is the “Wolsit” Coppa Florio racer (number 5531) as seems very likely from the above, it appears from research in the Brooklands Museum archive that it may be one of the earliest surviving participants at the Brooklands track (if not the earliest with its original rolling chassis). Racing commenced at Brooklands on July 6, 1907. The three “Wolsit” racers were tested at Brooklands either in late July or very early August 1907. The influence of the Brooklands testing may be seen in the introduction of 19 louvers per side on the bonnets and the reduction in the height of the dashboards on each of the three racing cars. This work was done after they had left the factory but before they arrived in Italy.

A 1910 Wolseley-Siddeley engine and gear box and other Wolseley parts have been purchased from Charles Neville in Canada (author of Wolseley Cars in Canada 1900–1920) and will be fitted to the car in order to rebuild it as close to its specification when supplied to John Ramsden as is now possible.

Driving the Wolsit

Though the badge on the radiator of this magnificent machine declares it to be a “Wolseley-Siddeley”, its history reveals it as the racing Wolsit, and specifically Wolsit 2, which finished the Coppa Florio in 1907 in the hands of Mark Wild. It sits rather majestically on Michelin 880 x 120-33 x 4 cable tires produced in Michelin’s plant in Milletown, New Jersey. This is a 1,200kg car, which makes it heavier by half than the 3.2 Lancia that we test drove last year and that you also see on these pages. It has a number of wonderful “parts bin” features: the rear axle is two inches shorter than the front because it was originally sourced from a different car for race purposes.

The starting procedure, as with most Edwardians, is somewhat ritualistic. It has right-hand steering but the driver climbs first into the passenger seat on the left to turn the key in the panel under the seats and stand on the starter pedal, and then moves over to the right. The switches have to be done in order, using only one bank of plugs for starting. The starter has to be operated with the cogs on the flywheel so a sense of timing and feel is required to avoid grinding the cogs. Advance and retard is a pull lever, the choke needs to be adjusted and then the second brass switch brings in the second bank of spark plugs. The throttle is in the center, while the foot brake is only a transmission brake for parking, etc. and is never used at speed. Braking is done by utilizing the lever out to the right, which acts on the rear only. The gear lever, also on the right, takes some getting used to. Going down the box requires two or three pumps of the clutch and the gear is fed in gradually, whereas the Lancia needed a more straight forward shove into gear.

Photo: Peter Collins

Once the noisy 10-liter Simplex engine bursts into life, the huge car trundles slowly off in first gear. My first opportunity to drive it was at a Goodwood test day, where other cars on the circuit had been warned of our presence, though this turned out to be unnecessary as we managed to embarrass some very modern cars! The first impressions are dominated by awareness of the significant torque from the big 45-bhp engine, the total impossibility of seeing anything behind without turning around and looking, and the ease with which a huge car can start to drift! The first corner after the pits is taken in top gear, which is held through Fordwater down to St. Mary’s, a sweeping right, and we go crunching down to third gear, holding third into Levant and then up the Levant Straight in top. The car achieves 80–90 mph easily on the fast part of the circuit and we use third for Woodcote to slow down as we approach the second gear chicane.

The car is very smooth as it accelerates round the wide Goodwood track, and it is far more nimble than it looks possible to be, but those are narrow, old tires and it breaks into a controllable slide fairly easily. Gear changing demands attention and good timing, and plenty of practice. The lack of brakes presents a few early psychological obstacles, but the braking is reliable provided you plan for it. It was clear to me that racing a car like this meant anticipating what might happen at any minute. If you pull the brake full on at 70 mph, not a lot happens, so it’s best not to get into situations where you need to do that! Once that is absorbed, however, full attention can be given to extracting the engine’s power. After some laps, I was getting to just over 90 mph on the quick bits, but I wasn’t yet ready for the 110-mph limit! The attempt does make you understand what Edwardian racing drivers might have been like…brave, tough and clearly lacking imagination of what could happen to them!

After the Goodwood test, we decided to get some more practice by running the Wolsit and the owner’s Lancia to a VSCC lunch time meeting in Sussex—the 25 miles giving some useful experience in ordinary traffic. This proved invaluable as I got accustomed to how much room needed to be left for braking, and by how much you had to anticipate whether a traffic light would turn red…I did miss one altogether!

Then on a warm July day it was off to Mallory Park in central England for a day of fantastic racing and 12 events for pre-war racing cars. Having raced a fair bit at Mallory, a pleasant 1.5-mile up and down circuit, I was not panicking at the thought of sharing a grid with 28 cars all built in the very early part of the last century…early Bugattis, a Sunbeam Indy car, Stutz, a couple of 1906 and 1907 Fiats, Mercer, Dodge, another somewhat later Wolseley, a Darracq…a fantastic array.

Practice was relaxed, and fairly late in the proceedings it was announced that a handicap would determine grid positions, though as these cars race so infrequently, the handicap was odd indeed. However, most of the competitors were just happy at the chance to race against so many other similar cars. Knowing that I was unlikely to be immensely competitive, I settled for the notion of surviving and learning. The torque available meant that I could probably save the strain on the gear box by only changing down once…to third…at the tight hairpin at the top of the hill. I tried it in second once to prove that I was right, and in fact it was much better to get the car balanced and slide it round the hairpin on full power in third, which brought it out to the downhill left turn onto the straight at impressive speed. Gerard’s Corner is a long, double apex right-hander at the end of the straight, and it is daunting. It took all the practice laps to find I could go in farther and farther and use less and less brake, but drifting on four-inch-wide tires takes some getting used to!

The race was nothing short of one of the best things I have ever done. Some very slow cars started on the front three rows, with some quicker ones behind, then some more slower ones, and even more quick cars. I was on the fourth row, and there were 10 seconds between each row as the flag came down. I had no idea how the handicap would work, but by now I had huge confidence in the car and just wanted to make it go as quickly as possible. I managed to catch the first slow platoon by the end of the back straight into the Esses, where there is a quick pull on the brake, a big right-hand drift, and then up the hill into the hairpin. My first cautious shift down to third and taking time to look over my shoulder found the eventual winning Sunbeam Indy car fighting to get past.

The remaining six laps saw the continuation of a very interesting learning curve, which included the notion that a heavy, nearly 100-year-old car, on four-inch tires, can do 100 mph and drift through traffic. But perhaps even more amazing is the fact that some nearly 100-year-old cars are much faster than this one! In the final analysis, the Wolsit was a big, but easily manageable, handful. The steering at speed is light and precise, there’s no roll…well, there isn’t much suspension…and it powers round corners in lovely lurid slides—though I clearly needed another 20 laps to learn to do that properly. The amount of respect I have for Edwardian drivers is enormous.

Owning and Running an Edwardian Car

I would refer you back to what we said about the Lancia sometime ago. You need to be a good historian to get a car of this age right. They are still out there, in unrestored condition, but you need to be an expert to take on the task. A car like the Wolsit, with its unique and important history, is however, a valuable asset…several hundred thousand dollars’ worth. Hence, my humble thanks to the owner for not only letting me drive it, but race it hard as well. Now, if we can only talk the Goodwood Revival into an Edwardian race, people will see something amazing.

Specifications

Chassis: 1907 40-hp Wolseley

Body: Two-seater racer body

Wheelbase: 10′ 6″

Suspension: Semi-elliptic rear springs supported by dumb-irons

Steering Gear: Std. 45-hp column 3″ longer

Engine: (Original Wolseley 40-hp) Benton & Stone pressure feed valve; cyl. ground out to “B” Std, 2-Drip lubrication; (current Simplex) 1916 10 liter.

Power: 45 bhp

Carburetor: 30-hp. C. hand choke

Clutch : Std. with special plain bearing thrust black

Gearbox: Darracq 1912 four-speed

Gears: 183/30-hp. B.Type

Hand Brake: 30 B.A. Type control

Foot Brake: 1 Std. 30-hp B. liner; bracket & drum

Axle: 196/30-hp B. Type live

Wheels: 880 x 120

Tyres: Front & rear Michelin Cable 880 x 120-33 x 4

Resources

Thanks to the owner for use of his detailed history of the Wolsit, and to the VSCC Bulletin for extracts from the owner’s article about the car.