Hollywood actors play them—Luigi Fagioli was one. Built like Rocky Marciano with wide shoulders, muscular arms, thick neck and a broad chest, his attitude could be as tough as his appearance and that could lead to violence when his temper took over. Fagioli was an explosive cocktail of hard-nosed single-mindedness, ruthlessness, chauvinism and driving talent that gave no quarter and expected none in return.

The “Abruzzi Robber,” as they called him, was a truly great racing driver. Though considered mercurial by some, he often beat men like Tazio Nuvolari and Rudolf Caracciola. He also won a total of 10 Grands Prix, including Monaco, Avus and Italy for Mercedes-Benz, Monza and Rome for Maserati and France for Alfa Romeo. And for more than 50 years, he has held the record for being the oldest driver ever to win a GP—the French in 1951—when he was 52 years old and racked with rheumatism.

A rebellious individual, the Tough Guy constantly disobeyed the fearsome Alfred Neubauer, once attacked teammate Rudolf Caracciola with a hammer, then a knife, and would abandon a Grand Prix rather than meekly bow to Mercedes team orders so that a slower driver could win. He was so conceited that he automatically assumed he was the number-one driver when he joined the much-vaunted Mercedes-Benz team, something a certain Mr. Alfred Neubauer was none too pleased about. And that meant trouble.

Born in Osimo, near Ancona on Italy’s Adriatic coast in 1898, the prickly Luigi Fagioli came to motor racing rather late in life, at 27 years of age, after having qualified as an accountant and helped to run the family pasta business. He bought himself a Salmson, considered the best 1,100 cc of its day, and set about cutting his teeth on minor events: he competed in 24 of them, but only won two between May 1925 and November 1926. He then bought an 8-cylinder 1,500-cc Maserati in 1928 and campaigned both cars—first came the class wins and then, by mid-1930, they gave way to overall vic- tories in provincial races like the Coppa Principe di Piemonte and the Coppa Ciano, named after Mussolini’s son-in-law and one-time foreign minister of fascist Italy. Fagioli did well in his first Grand Prix in the Maserati 26M, working his way up through the heats to the front row of the Grand Prix of Monza grid and taking 5th overall. The start of the following season signalled an even greater improvement, with Luigi driving his 26M into 2nd place, behind the dashing Louis Chiron’s Bugatti T51, in the season’s first Grand Prix, at Monaco. Before retiring from the 1931 Grand Prix of France, the Italian turned in the race’s fastest lap, after which he finished 2nd to Achille Varzi in the Grand Prix of Tunis. All very promising.

Soon the motor racing fraternity began to sit up and take notice of this 33-year-old accountant: Maserati gave him one of its supercharged 4.5-liter, 16-cylinder cars for the 1931 GP of Monza, which he won brilliantly by clocking speeds of over 150 mph—and here we are talking about more than 70 years ago! Maserati must have thought they had made absolutely the right move, because to win the race the Tough Guy trounced the Alfa Romeos of Tazio Nuvolari, Nando Minoja and Baconin Borzacchini, plus the Bugattis of Varzi, Chiron and Marcel Lehoux.

With that victory, Fagioli became a newly minted Italian motor racing hero, who was about to cause all sorts of havoc on the international stage.

Fagioli kicked off 1932 with a 3rd in the works Maserati at the GP of Monaco, behind winner and the-man-to-beat Tazio Nuvolari, and his future teammate and object of his later ire, Rudolf Caracciola. This was followed soon thereafter by victory in the Grand Prix of Rome. But his greatest moments that year were his two epic battles at Monza with Tazio Nuvolari. One was in June in the town’s own Grand Prix and the other in September, during the GP of Italy, both races won the hard way by the Flying Mantuan with the Tough Guy hounding him every inch of the way to eventually take two 2nd places. Luigi finished 2nd to Chiron again at the Czech Grand Prix, but by this time, he was sick of playing second fiddle. The Tough Guy soon started to flex his muscles.

This period coincided with Alfa Romeo retiring from motor racing and passing its banner to Scuderia Ferrari. But all was not well at Ferrari and this was soon to play right into Luigi’s hands. Fagioli believed he had just as much driving talent as the stars of his day, but not in the Maserati, which was unwieldy and physically drained him. So he did a deal with Enzo Ferrari and switched to the Scuderia’s Alfa Romeos for 1933. He took Tazio’s place, which must have done Fagioli’s ego a power of good, after the Mantuan’s string of heated arguments with the Commendatore. This suited Enzo Ferrari nicely, because he was able to show that Nuvolari was not indispensable. It suited Fagioli even more, because taking over from the great Tazio said a lot of the right things to a lot of people. Namely, that he had hit the big time.

Fagioli quickly went to work in ’33. After warming up with a 5th at the Gaisberg hill climb and a 4th in the Grand Prix of Nice, he turned in a string of three victories, including the Coppa Acerbo and the Grands Prix of Comminges and Italy; the victory at Monza being especially tasty, because he beat Nuvolari, who was driving his own Decimo Compagnoni–prepared Maserati 8CM. To cap it all off, Luigi was declared champion of Italy for the first time at the end of the season. But not before he finished 2nd to Chiron twice more, in the Czech and Spanish GPs.

Of course, the Tough Guy’s most impressive win was in that year’s Italian Grand Prix at Monza, those bloody races in which Giuseppe Campari, Baconin Borzacchini and Stanislao Czaikowski were all killed. Fagioli and Nuvolari alternated in the lead a dozen times during the event’s 310 miles, each determined to win his homeland Grand Prix. But on the penultimate lap, Nuvolari had to pit his 3-liter Maserati with a flat tire and that relegated him to a permanent 2nd place. This time the great Tazio had been beaten by a relative newcomer, Luigi Fagioli, who also set a fastest lap of 115.59 mph and covered the distance at an average of 108.14 mph.

AIACR, motor sport’s governing body at the time, changed the rules for 1934 in the hope of slowing Grand Prix cars: that was the year single-seaters could be powered by engines of unlimited cubic capacity, but their curb weight had to be no more than 750 kg. The sanctioning body thought limiting the weight to 750 kg would, by implication, mean engine power would be reduced to around 2-liters, but they got that one wrong. Egged on by Hitler’s annual 250,000-mark bonus per team as well as smaller sums for race wins, hi-tech Daimler Benz—making its return to motor racing—and Auto Union eventually managed to squeeze engines of up to 6-liters into their cars and still meet the weight limit. The best the Italians could manage was 2-liters at first and, at a push, 3.2-liter power units later.

However, back at Mercedes, Alfred Neubauer was short of good drivers. There was a question mark over the physical and mental fitness of his friend Rudolf Caracciola, who had been maimed in a horrific accident practicing for the 1933 Monaco GP—his right leg had to be shortened by two centimeters and rebuilt. While he was recovering at his mountain chalet in Arosa, Switzerland, Rudolf’s beloved wife, Charly, died after a skiing accident at Lenzerheide a few miles away.

What a problem, Neubauer mused; the team’s other drivers, Manfred von Brauchitsch and Ernst Henne, had no experience of circuits outside Germany and other available German driving talent was thin on the ground. So some new and experienced blood was needed. Cue the Tough Guy, who Neubauer quickly engaged. But the German did not know all hell was about to break loose.

With one teammate physically and mentally incapacitated and the other two wild and inexperienced, Fagioli considered himself the number-one Mercedes-Benz driver. But Neubauer thought differently and made it clear to Fagioli that he would only be allowed to win if a German could not. The Italian was to be a makeshift driver, one who was capable of beating his German colleagues, but would not be allowed to do so all the while they were in the running. The Tough Guy regarded this as an insult not only to himself, but also to his country. Both were, in his mind, relegated to being second class. So Fagioli quietly declared war.

Two Mercedes-Benz W25s were entered for the Eifel GP at the Nürburgring for von Brauchitsch and Fagioli, but when they were weighed, the cars scaled in at 751 kg, one kilo over the maximum. After a lot of hand wringing, Neubauer gave the order to strip the cars’ white paint back to their bare, silvery alloy and that made them legal—in the process the Silver Arrows were born. Mercedes and Auto Union never again reverted to Germany’s white livery, but kept to that dull silver color that earned them their legendary nick-name.

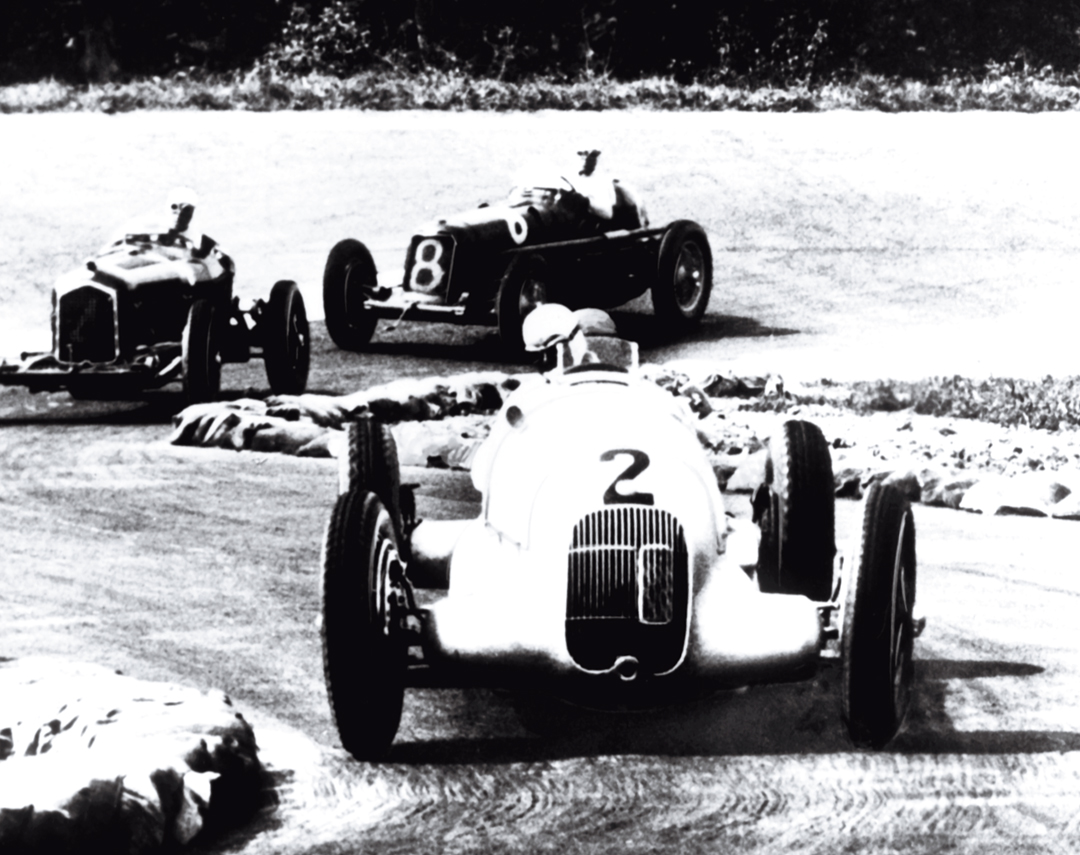

German nobleman von Brauchitsch shot into the lead of the Eifel GP but Fagioli soon overtook him, much to Neubauer’s displeasure. How would it look if an Italian won instead of a supposedly invincible German? So the Mercedes team boss ordered Fagioli to let von Brauchitsch pass, which he did. But he took his W25A right up to the rear end of the Brauchitsch car and stayed there, harassing the wild, twitchy German as if he were about to overtake.

Photo: DaimlerChrysler

When Luigi made his first pit stop, he was fuming, and bellowed his annoyance in an avalanche of Italian that Neubauer did not understand. Not to be outdone, the mighty team boss boomed orders back to Fagioli in German, which Luigi did not understand. But both got the picture. Fagioli roared off in a cloud of blue tire smoke and stubbornly took up station right on the tail of von Brauchitsch’s Mercedes once more. After 13 farcical laps, and another pit stop during which the lumbering Neubauer and the tough little Abruzzese hollered at each other again, Fagioli had had enough. He climbed out of his perfectly healthy Mercedes-Benz W25A in mid-race and stalked off, leaving his driverless car stranded in the pits. If he could not drive to win, he would not drive at all.

Both men had a problem: Neubauer had a major disciplinary challenge on his hands one race into the season, and after telling the German team boss where he could stick his orders, Fagioli now knew he had little chance of winning with that team—unless he took matters into his own hands.

Mercedes held a test session at Montlhéry in mid-summer 1934, where Nuvolari’s lap record stood at 5 minutes, 19 seconds. Still in pain, Caracciola managed to nudge the Italian’s time with a 5 minutes, 20 seconds time, but von Brauchitsch went the whole hog and clipped four seconds off the record. Better was to come, as far as Neubauer and Mercedes were concerned: Fagioli did three laps, setting a new record with each one, until he got his time down to 5 minutes, 11.8 seconds; a saber-rattling job on Auto Union if ever there was one.

But the saber rattling turned out to be a rather feeble gesture in the end. Hans Stuck, in his Auto Union, chopped a massive five seconds off the Fagioli record and Louis Chiron did even better. Fagioli hurried into his W25 in an effort to beat the Frenchman, but he could only equal the Monegasque’s time. Then the Italian was shafted in no uncertain terms by von Brauchitsch, who turned in 5 minutes, 5.6 seconds—and there the record remained.

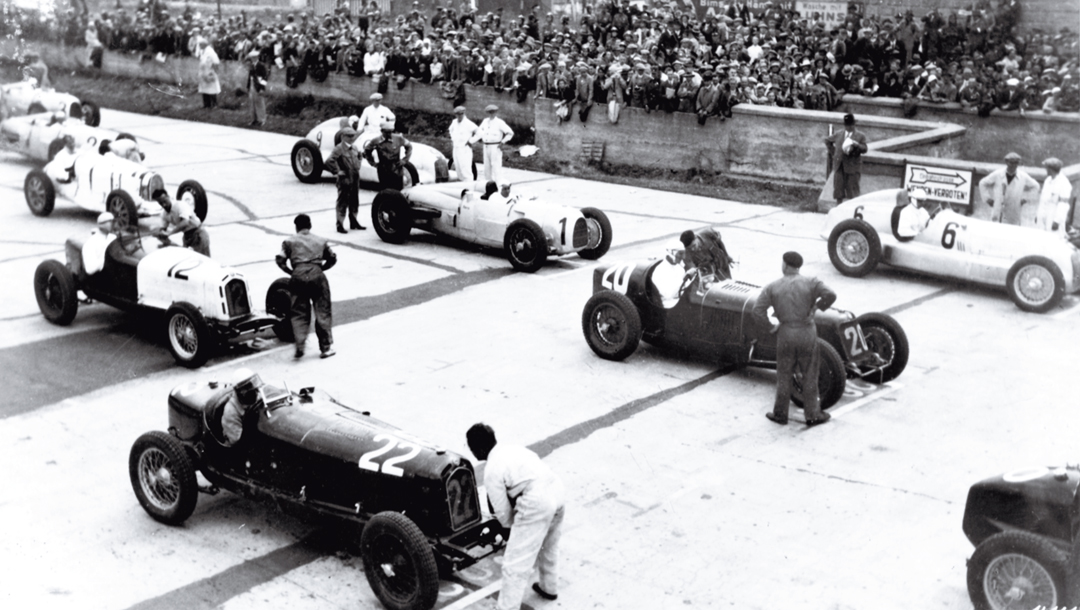

Photo: DaimlerChrysler

However, Fagioli was even more peeved to find himself on the back row after the draw for grid positions—which is how they did things in those days—had been completed. As the race progressed, he soon worked his way up to 3rd and then crossed swords in a daring duel with the three musketeers, Stuck, Chiron and Caracciola. Luigi eventually took Caracciola in an Alfa and was nibbling away at Chiron, when his brakes gave out. By that time, von Brauchitsch had already retired and Caracciola did so soon afterwards: victory to Chiron and his Alfa P3. In the end it was undoubtedly not one of Germany’s finest hours, with Mercedes knocked out, its broken hero Caracciola out of it, von Brauchitsch on the pit wall and even the team’s Italian sidelined. Fagioli was seething. No victory, no fastest lap, no record and a start from last place on the grid. Things had to look up. The million reichsmark question was, how?

To add to Fagioli’s headache, it seemed Caracciola was slowly on the mend. The German put up a fabulous performance at that year’s Grand Prix of Germany at the Nürburgring, which severely exercised his rebuilt right leg. Hans Stuck took the lead for Auto Union, but Der Regenmeister and his Mercedes-Benz hounded the Type C all the way, eventually passing Stuck on the 13th lap—but was put out on the 14th lap with a blown engine. Fagioli kept at it and eventually brought his Mercedes home in 2nd, but he could not have been pleased at the surprisingly adroit performance of Caracciola, who began to assert his claim to number-one status at Stuttgart.

Later, Fagioli won the Coppa Acerbo, all right, but Rudi had led the race for 11 laps before crashing out after making an almost-unheard-of driving error in a race that saw Guy Moll perish in a crash.

Mercedes was all but wiped out in the Grand Prix of Switzerland at Bern, with Fagioli the only one to save a little German face with a struggling 6th place, behind victor Hans Stuck again in the Auto Union, followed by a gaggle of Alfas and a lone Bugatti. But the Tough Guy soon became a kind of motor racing “Seventh Cavalry” who burnished the Mercedes image again in no uncertain terms, by winning both the Grands Prix of Italy and Spain.

Photo: DaimlerChrysler

The Monza race looked like it was going to be an unexpected routing by Rudolf Caracciola, who laid in a strong 2nd place and constantly challenged Hans Stuck for the lead during a demanding opening 39 laps. By that time, Fagioli had retired with supercharger trouble and was pacing the pits irreconcilably. But with so many chicanes to change gear and brake for, Caracciola came into the pits for more tires and in a sorry state. The German was drained, unable to lift a finger, exhausted, so much so that the mechanics had to lift him bodily from the cockpit. The pacing stopped as Luigi was motioned to Rudi’s car, with which the Italian won the race before a delirious home crowd who, like him, could not believe their luck.

Spain? That was a race of Italian duplicity. Stuck was leading again, but retired after five laps and that let Caracciola through into the lead, followed by an aggressive Fagioli. To save the cars—and his friend Caracciola—Neubauer ordered Rudi to ease his pace as he had a good lead, but that played right into Luigi’s hands. Fagioli pressed his “teammate” hard and eventually passed Caracciola to the incandescent fury of Alfred Neubauer.

The unrepentant Fagioli got himself past the leading Auto Union of Hans Stuck at Brno during the last Grand Prix of the year and built up a good lead, only to see it ebb away as he pulled in for an unscheduled pit stop. Stuck fended off Fagioli’s attempts to retake the lead and won the race.

All of which left Fagioli to mull over a fairly satisfactory first season, and a rather ruffled Mercedes to ponder his insurrection.