1962 Lotus 22

Although current CART drivers Adrian Fernandez and Michel Jourdain might want to argue with this premise, there have not been many motor racing stars to come out of Mexico. In the wider world, only Ricardo and Pedro Rodriguez have a significant reputation and that has as much to do with their charisma and early deaths as with success. Somewhat later Hector Rebaque, a wealthy young man with family backing, made it into Formula One, and was a reasonable driver whose name still lingers in some memories. But who else?

Moises Solana

There was only one other really capable Mexican racing driver, Moises Solana, who had the bad fortune—perhaps—of coming onto the motor racing scene at the same time as the Hermanos Rodriguez. Unfortunately for Solana, the Rodriguez’s caught the public imagination in Mexico and immediately started racing internationally, which, in turn, made them into international stars. This overshadowed the fact that Moises was probably their most serious competitor when they raced together in Mexico. Younger Rodriguez brother Ricardo beat both Pedro and Solana into a championship Grand Prix race, managing to start in late 1961 for Ferrari, on the front row at Monza in the Italian Grand Prix. Pedro and Moises didn’t manage a drive until 1963, with Pedro getting into a works Lotus at the USGP at Watkins Glen and in Mexico, where Moises made his F1 debut in a rather secondhand Centro Sud BRM P-57. Both sets of Mexican families put money up for their sons to get into F1, but they all had a fair degree of talent. In some ways, Moises’ Grand Prix drives were extra impressive because he wasn’t getting the international experience the brothers were in racing sports cars. Six of Solana’s other F1 drives were for Lotus in 1964, 1965, 1967 and 1968, while in 1966 he appeared in a Cooper-Maserati T-81. His results are not impressive but he was a hard-charging driver, and he was never dismissed by the regulars. He was 11th qualifier in his first race, finished 10th in his second, qualified 7th for the 1966 USGP and always managed at least a mid-field qualifying spot, which was pretty good if you only got in the car once or twice a year! He earned some respect, if not results or points in his eight Grand Prix events.

Photo: Casey Annis

However, Formula One aside, Solana was a champion. He was a Mexican Jai-Alai star, starting to play from an early age in the fierce and physical racquet sport, joining the Mexican team in 1952 and enjoying star status all through the 1950s. His counter to the Rodriguez international stardom was to become that Mexican rarity, a sporting superstar. To some extent his early celebrity assisted him in getting some drives in races, but only partly as racing was in the Solana blood; as his father and several uncles raced. In later years, his cousins and nephews would follow suit. Like the three generations of the van Beuren family, the Solanas raced, with long distance open road races being a specialty. In fact, Mexican road racing has a long and fabulous history going back to the beginning of the 20th century, yet it has never been adequately documented, and there were some great drives and drivers, though their fame never spread nor lasted.

Moises had his first race in the grand daddy of the big road races, the Carrera Panamericana, where the 18-year-old scored a 6th place on the Tuxtla stage in a 1953 Dodge. Jai-Alai was Solana’s big activity over the next few years but he won another road race in 1957 in the same Dodge. In December 1959, he raced an Alfa Giulietta at the Mexico City Autodromo to 2nd place, one of the occasions he wasn’t up against Pedro Rodriguez, who was at the time driving a Volvo in the compact car race supporting the USGP at Sebring. Solana raced a Corvette and the Alfa throughout 1960 and 1961, as well as a DKW, and in that year he also started racing in a Formula Junior Lotus 18. He had a number of successes, bought a Lotus 20 F.Jr. in 1962 and, later that same year, he ordered a new Lotus 22 F.Jr. from the Lotus factory, the very car you see on these pages.

Lotus 22-J-18

It doesn’t seem very likely that I would need to tell VRJ readers what Formula Junior was. To be absolutely to the point, it was “invented” by the Italian Count Giovanni “Johnny” Lurani in 1958. It was intended to be a single-seater training ground, with cars that looked like period front-engine Grand Prix cars, only smaller. To start, they were all Italian, and then the Brits got involved, Lotus came along, killed off the front-engine cars, it became a more expensive training ground, and was really all over by 1963, replaced by new formulae.

As the new F3 and F2 classes prospered, there was limited use for lighter Junior chassis, and for years they lingered in garages and lofts, until historic racing found a place, and now they are vastly more expensive than an F1 car was in 1960!

But when Formula Junior first appeared, it really did serve the purpose. It was the karting equivalent of the time—all serious drivers who wanted single-seater careers drove in Formula Junior, and Moises Solana was one of those people. The Formula Junior category wasn’t so successful as the class in the USA and Mexico, but there was some good competition. A good Junior driver could get a ride at an international event like Sebring or Nassau, and when Moises Solana bought his Lotus 22, he knew it was the car to have.

Photo: Casey Annis

Virtually all the early Italian Juniors had Fiat 1100 engines, the regulations stating that the engine had to be derived from a touring car of which at least 1,000 units had been built. There were BMC and Ford units in the British cars, the Lotus 18 having a Cosworth-developed 997-cc Ford in 1960. The smoother, sleeker Lotus 20 came along in 1961 with the same engine. The multi-tubular chassis being slightly stiffer than the one in the 18. The works drivers Trevor Taylor and Peter Arundell dominated the racing in the Lotus 20 as Jim Clark and Taylor had done in 1960.

Then along came the Lotus 22 for 1962 and, in addition to an improved chassis as on the 20, the 22 had disc brakes on all four wheels. The rear suspension incorporated ideas from the F1 car, and with the Cosworth-Ford engine in the chassis at an angle, the center of gravity was lower, improving the handling significantly. In 1962, Taylor moved on to the Lotus F1 car and Peter Arundell got the job as the official works number one driver. All told, he racked up 18 wins in the Lotus 22, and three 2nd places in 25 starts. The engine was now the famed Cosworth development of the Ford 105E engine with a capacity of 1097-cc. Mike Spence, Bob Anderson and Alan Rees (the R in MARCH) all did well with the 22, though Giacomo “Geki” Russo won the Italian F.Jr. Championship with a DKW-powered 22. The 22 was adapted for F3 in 1964 and a few years later was revised, though not much, appearing as the Lotus 51 Formula Ford. I raced one in the day and it certainly wasn’t much different from a Lotus 22, at least in the chassis department.

The final Lotus Formula Junior was the 27, which came out in 1963, and it was the ultimate development for the formula, being a monocoque, though it has to be said it wasn’t very good until the flexible chassis was sorted. Arundell did manage to win the British Championship but it was clear by then that F.Jr. would soon fall by the wayside. Among the many notable drivers to pilot the Lotus 27 were Mike Spence, Jo Schlesser and saloon and rally car driver Peter Procter, who has only just returned to historic racing. While the 27 is the “ultimate” weapon today, it didn’t have the dominance of the 22 in the period. Lotus was quite proud of its achievement of having its four Junior models win more than half the International F.Jr. races they contested.

Photo: Casey Annis

Thanks to the current owner of the Solana car, Keith Wintraub, the records of 22-J-18—18 meaning it was the 18th Lotus 22 built—are extensive and up to date. Solana ordered the car on August 22, 1962, with the original invoice signed by Lotus’ Peter Warr. Its first race in Moises’ hands was on September 23 at the Il Premio Independencia meeting at the Mexico City Autodromo, where the Mexican scored a debut victory for the car in its attractive gold, black and light blue. Solana had a number of exciting races with his countrymen, Ricardo and Pedro Rodriguez, and he did manage to beat Ricardo’s Pepsi-sponsored Cooper, though this was in late 1961 in his Lotus 20. These races were what brought Solana to the attention of the Lotus team and helped to gain him the Grand Prix drives later.

Moises had wins with the Lotus 22 through the end of 1962 at places like Mexico City, Toluca and Cuernavaca, and carried on in the beginning of 1963. Solana also contested and won hillclimbs as well, winning at Pachuca, Toluca, Zacatenco and Mexico City. In 1964, he won in Acapulco, in 1966 in Pachuca, Guadalajara, and then he more or less put the car away, as by this time he was driving a wide range of other cars and had had his first Formula One experience. Considering that he drove the Lotus 22 for more than four years, he clearly must have loved it, and it provided some 19 victories and many good placings during that period. This long list of consistent results would appear to make this the single-most successful Formula Junior car to have raced in the original Formula Junior period.

From 1963 on, Solana raced his DKW, a Chevy II, an occasional Ferrari 4.9, a Volvo (possibly one of those from Pedro Rodriguez, who was a Volvo agent for a short period), a Mini-Cooper, a huge Ford Galaxie (which was used for town-to-town races), a Corvette, a Chevelle, a Renault 10, a Mustang and a Ford Cobra. After the Lotus 22, Solana had a Lola T-70 Mk.III, which he also raced in Nevada and at Riverside. In 1968, he moved up to a Group 7 McLaren, in which he was again very successful, as he had been in the Lotus and Chevelle. On the 27th of July, 1969, Solana should have dominated the hillclimb at Valle de Bravo-Bosencheve, but inexplicably his McLaren M6B left the road in a huge accident which killed the able Mexican instantly.

Driving Moises’ Lotus 22

The Lotus 22 found its way into the family barn, where it remained for 25 years before it was discovered by Brian Goellnicht, who was in Mexico to visit the Solana family with a view to purchasing Moises’ Lola T-70 Spider. He discovered the Lotus 22 and knew that fellow historic competitor Toby Bean wanted a 22 and so organized the purchase of the car. He then undertook a very serious restoration with the help of Joaquin Solana, who puts a great deal of effort into keeping Moises’ reputation and story alive. He keeps a small museum at his house in Mexico City, which I visited while doing some research in 1997, and I had the chance to meet some of the generations of motor racing history in the Solana family. I spent a wonderful day with Moises’ brother, Hernan, who restores cars in Mexico City and was still running a Hudson in the Carrera Panamericana.

Bean raced the car for several seasons with a number of successes and his interest in sports, rather than single-seaters, led him to sell it to Keith Wintraub in 2001. Wintraub had the car returned to its original colors, and it continues to race, being looked after by Butch Dennison.

It was in the company of our editor and Butch Dennison at Firebird, Raceway in Phoenix, Arizona that I confronted this jolt from the past. Wintraub was fairly surprised that I knew the car instantly, having seen the photos of it in the Solana family album and on their walls, as well as hanging in the office of the Mexican Automobile Federation. It’s a stunning car so it sticks in your memory, much as my own Lotus 51 has. Dennison was officiating over an F1 test drive that we were doing for VRJ when Wintraub kindly asked if I wanted to sample his piece of history, as well. It was amazing that something that small could follow two F1 cars and yet be every bit as much fun to drive!

Now the Firebird complex we were using that hot March morning in the Phoenix desert is tight and twisty, hard work for F1 cars but fantastically challenging when you have permission to “go for it.” As someone without a great deal of F1 experience at the hard end, this was pretty daunting, though the stories will last me for years! The Lotus 22, however, was like driving a “real” car, something I could relate to, and feel very comfortable in, and indeed it instantly brought back the memory of my 12 races in 1971 in the Lotus 51. The chassis, the cockpit, and the feel in the car were much the same. I loved that car because it was so much fun to drive, and for this non-mechanic, it was ideal. I bought it for £500—with a trailer—to do 10 races to get my international license. I did 11 races in 8 weeks, got my license, and sold the car for what I paid for it and kept the trailer. It never stopped or broke in the time I had it. No wonder anything similar seems so nice.

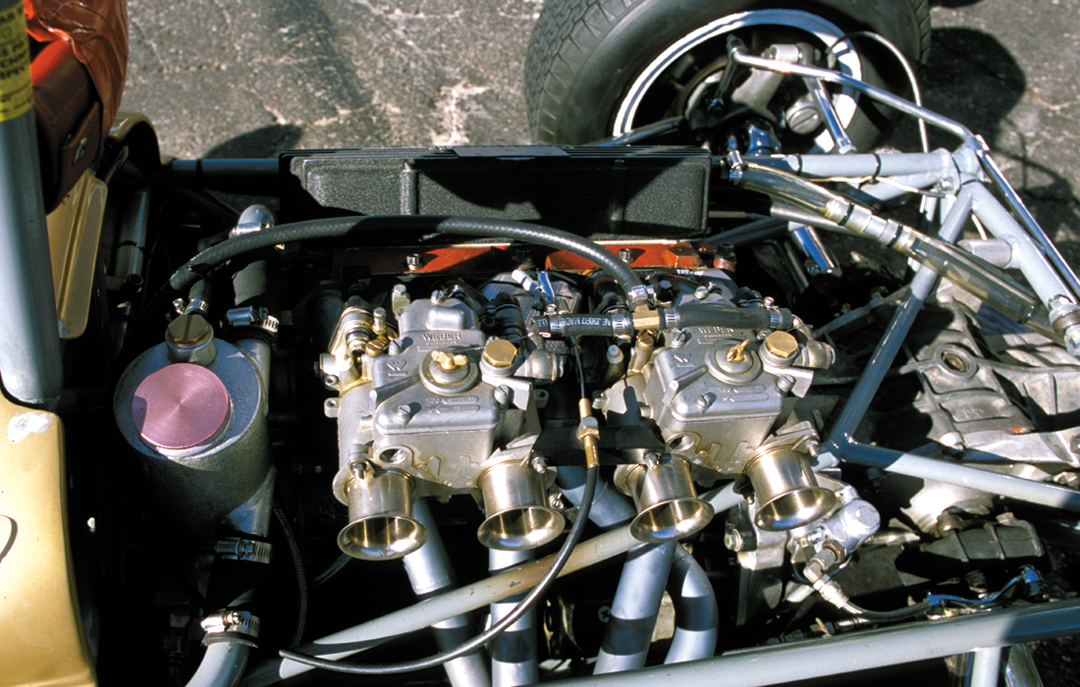

Of course, the Lotus 22 fooled me instantly into thinking it would be so easy and much less of a handful than the F1 cars. What I had forgotten was how lively a much smaller and lighter car with just about as much torque is. The Formula Junior with that Ford engine and double twin choke Webers is potent and punchy, and the first tight corner with too much throttle immediately threw the back end around quicker than I could say it was happening, though it was equally easy to catch and keep on the black stuff with a more judicious use of the throttle.

The Lotus 22, is, in fact, not the same as the more stodgy 51. The five-speed Hewland box means you can use the revs more flexibly, and keeping the revs up on entry to a tight corner allows use of third gear rather than second, but only if you are able to balance the machine. The independent rear can be very “independent” until you build serious smoothness into your line through twisty bends and swooping off-camber corners. The 22 seems to like being pushed towards its limits so you can see what it will do, then goes quicker when you back off and do it smoothly. This is true of many racers, but seemed so apparent in this one, especially after driving both a Ferrari and a Tyrrell.

Five or six laps allowed a degree of slide into most of the Firebird corners, less braking, more progressive use of the throttle in the apex of the corner without overdoing it on the exits. I began to see why Moises might have liked this car so much, as it soon builds up that sense of rhythm where one corner begins to flow into another. The F1 cars were too daunting to get that far in a short space of time, but the Lotus 22 practically begged for it. Keep it settled, keep the revs up, let the back end find some bite, loosen the grip on the steering wheel, feel the back coming round, and feed the power in, immediately lining up for the next corner. In ten laps, I totally lost track of where I was on the circuit, as one corner just turned into another and the little gold device felt its own way round.

Buying and Running a Lotus 22

I haven’t done the calculations, but the torque and power-to- weight ratio must not be that far off the F1 cars of the period. The later Formula Junior cars were putting up times that weren’t a million miles off their bigger brothers. One thing this driving experience brought home was how good the handling had become on the later Juniors. While watching the Formula Junior race at the last Monaco Historics, I thought these cars must have been improved, but I realize now I was wrong. The quicker cars were so good at putting the power to the ground and sticking to the road that they were fantastic on tight circuits. No wonder the price of buying a Formula Junior is going through the roof.

A good sound Formula Junior car is not that complex to run. It all depends upon what your objectives are. A season of moderate vintage racing probably won’t force an engine rebuild. But if you want to do Monterey and Monaco, the car will get serious wear and so will your bank account. It is hard not to look at a good Formula Junior as an investment these days. They have become so popular, they just are. Our last Market Guide had the Lotus 22 in top condition at around $40,000, but with some Coopers without serious history getting over $50,000, something like the car you see here is particularly valuable. For me, though, this was a priceless experience.

Specifications

Chassis: Multi-tubular space frame.

Suspension: Front: Unequal-length wishbone and coil-spring/damper units. Rear: Independent by single lower wishbone, fixed-length articulated drive shaft and coil-spring/damper units with a top link.

Engine: Cosworth-developed Ford 105E

Capacity: 1098-cc

Power: 102 bhp @ 8000 rpm

Carburetion: Twin double choke Weber 40 DCO

Steering: Rack and pinion

Brakes: Girling discs on four wheels, 9inch x 3⁄8 inch.

Transmission: 5-speed, Hewland Mk.6

Wheels: Magnesium bolt-on

Tires: Front: 4.50 x 13. Rear: 5.50 x 13

Resources

Cowdrey, B. Formula Junior Racing Cars Remembered, 1993 Bookmarque Publishing ISBN1–870519–27–2

Ramirez, D. Moises Solana–Tradicion O Leyenda, 1994 Alfonso Tovar Publishing ISBN–970–91470–0–5

Many thanks to Keith Wintraub, Butch Dennison and to Hernan and Joaquin Solana for bringing Moises “back to life” for me.