The truth is, I might have missed him amongst Moss, Brabham, Trintignant, Shelby, Ward and all the other motor racing luminaries at Monterey if someone hadn’t pointed him out.

“That’s Norman Dewis,” my friend said, pointing to an amazingly spry white-haired man of small stature holding court with an enthralled group of enthusiasts. As it happens, Dewis had driven the very same ex-works D-Type Jaguar they were standing next to at Goodwood 45 years ago and would drive it again in the Historics that day – at the tender age of 80. But while his driving skills are better than most, it isn’t driving that Norman Dewis is most known for.

To anyone familiar with the history of the British marque, four important men are usually associated with the great Jaguars of the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. Obviously, headman and founder Sir William Lyons, first and foremost. Under Lyons, three others worked closely to produce Coventry’s best; chief engineer William Heynes, aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer, who sculpted Jaguar’s styling, and Norman Dewis. As chief test driver for Jaguar from 1952 through 1988, Dewis’ job was to test and develop every new design, from the first prototypes to the final production version, some 25 models in 36 years.

The XK120 and C-Type Jaguars had already been introduced before Dewis came on board, but one of his first important tasks was to develop a then new technology that has ultimately affected all of us who drive a modern car. Under the cloak of secrecy, Dewis developed the first disc brakes to be successfully applied to a full-size car, the C-Type Jaguar. Jaguar proved the worth of disc brakes at Le Mans in 1953 with the C-Type, and in ’55, ’56 and ’57 with the D-Types, the last two, privately owned.

From the very beginning, Dewis was heavily involved in the development of the D-Jaguars, Malcolm Sayers’ lighter, lower, more aerodynamic – and incredibly beautiful – three-time Le Mans winners. On the Sarthe circuit’s three-mile long straightaway, no one could match the wind-cheating Jags’ top end or go as deep as their cherry-red glowing discs allowed at the end of the straights, but outright power was another question. New eight- and twelve-cylinder racing engines from Ferrari and Maserati had overtaken Jaguar’s long-lived six. Jaguar engineers had begun drawing up their own V12 as early as 1955, but the following year, the works officially retired from racing.

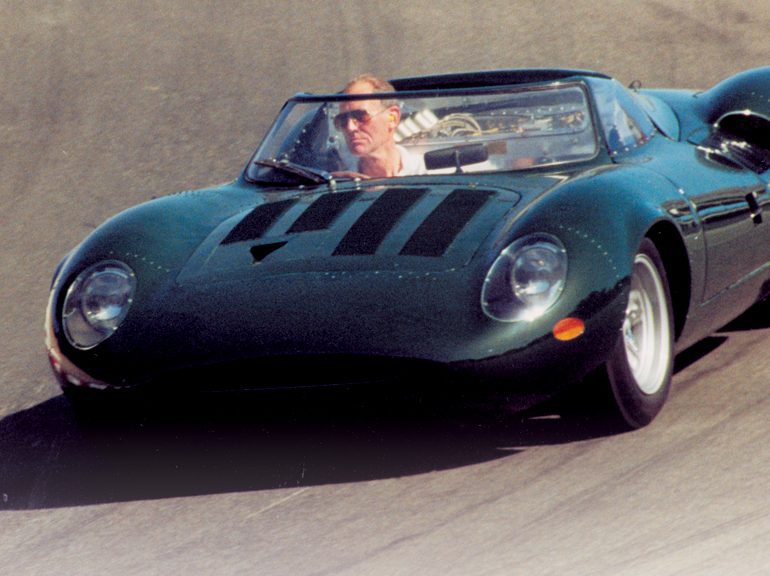

Norman Dewis’ work never stopped. He developed the disc brakes that would go on Jaguar’s line of cars in 1958 and did the development on Coventry’s sensational E-Type introduced in 1961. By the mid-sixties, the V12 had become a reality and Malcolm Sayers had created yet another beauty to house it, the ill-fated mid-engine XJ13.

“That was me favorite,” Dewis told us at Monterey. “We only built the one and the idea was to get back to Le Mans. It was drawn up enough by ’65; by ’66 we’d produced the car. That was the first V12 engine we put into a car.”

The trouble was that Jaguar had become a part of the Leyland Group and a strict no-racing policy was mandated by their management.

“That was probably one of the biggest mistakes ever made by Sir William. I mean he never should have let that happen. So the whole thing stops. We have the most beautiful mid-engine car, cigar-shaped, beautiful shape, and we’re not allowed to race, or even to start development. Sir William sent instructions down, on no account was I to drive it or take it out of the factory.”

Dewis had no choice but to grudgingly go along with the order and “the 13,” as the car was known to insiders, lay frustratingly untried day after day.

“So after about three weeks, there’s the car, all ready to be fired and go. And my boss (William) Heynes, he was quite a character – we got on well – he came in my office. We were talkin’ about one or two things and he said, ‘By the way, the 13, what do you think?’ I said, ‘It’s a disgrace. We ought to…I’d love to run it.’ He said, ‘I know you would.’

“I said, ‘Are you giving me permission?’ He said, ‘No, no, I can’t. I just thought you might, uh, get a bit itchy and you might like to try it.’ He said, ‘It would be nice, wouldn’t it? But as you say, we can’t do it.’”

“Official” permission or not, Heynes’ message was clear. He too wanted to know what the XJ13 would do, but Dewis would be on his own.

Dewis assembled a few trusted staff members and told them to meet him at the factory very early on Sunday morning.

“I said, ‘Don’t say a word to anyone, but we’re going to MIRA to test the 13.’”

It was at this clandestine Sunday morning run at MIRA, the Motor Industry Research Association’s test facility, where Malcolm Sayer’s last ground-up racecar first turned a wheel under power. It was to prove a handful for Dewis.

“It was very bad on handling. I mean, even the steering straight on was bad. The roll stiffness was all wrong.”

Nevertheless, anxious for some kind of result that might excuse his outright disobedience, at about midday, Dewis called for stopwatches and took the XJ13 out onto the outer circuit, a 2.8-mile triangle with banked turns and one flat straightaway, where he’d set the lap record years before in a D-Type at 155 mph.

“It was behaving terribly, but I did get one fast lap. It came out to 156, just over 156. So I wrapped it up and said that was it. I said, ‘Take the car back and don’t say a word to anyone.’ Of course,” he shrugged, “I knew what was going to happen on Monday morning.”

It did. Dewis was immediately summoned to “the old man’s” office, where Lyons angrily confronted him.

“Where were you yesterday?” demanded Sir William.

“I said, ‘Yesterday, oh, that was Sunday, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” Lyons growled, “but where were you?’”

“I said, ‘I’m trying to think.’”

“You were at MIRA with the 13,” snapped Lyons.

“‘Oh, yes,’ I said, ‘I was. It was only just a quiet run to try it out a bit.’”

“But I instructed that it hadn’t better leave the factory.”

“‘Well,’ I said, ‘that was three weeks ago. Surely, I thought you might have changed your mind.’”

“No,” spit Sir William, “when I give an order, I expect it to be carried out. You’ve totally disobeyed my instructions.”

“Yeah,” admitted Dewis, “I probably have. But before you discipline me, can I just tell you about the car?’”

Lyons nodded yes.

“I said, ‘It’s a fast car, or it will be.’”

“How fast?” Lyons shot back.

“I said, ‘Well, it’s gone faster than the D-Type at MIRA, 156.’”

Sir William took a breath. “A hundred and fifty-six on first start-up?”

“I said, “Yeah.’”

“So it looks promising?” Lyons asked brusquely.

“I said, ‘We ought to carry on with it.’”

“Oh, no,” Lyons said resolutely. Then, after a moment, adding with just a trace of a smile, “Look, I’ll tell you what we’ll do. You can carry on testing and developing it, but only on Sundays. Not in the week.”

And thus the XJ13 became what was called the Sunday test car. Norman Dewis continued to sort out the car’s handling every Sunday for several months, eventually lapping the MIRA circuit at 161 mph.

“It was the highest speed that had ever been obtained on British soil, and to do that, I got it up to 186 mph down the straightaway. So on Mulsanne straight, which was a lot longer, we probably would have seen over 200 mph. Easy. So, that was it. We proved the car was ready for Le Mans.”

And with 502 hp at 7600 rpm and 386 lb-ft. of torque at 6300 rpm from an essentially undeveloped racing version of Jaguar’s future V12 sports car engine, a true works racing XJ13 might well have been competitive with the Ford GT40s and Ferraris of the time. No one will ever know, as the XJ13 was retired in 1967 without ever being raced.

Ironically, four years later, Dewis was asked to drive the XJ13 one more time at MIRA for a film celebrating Jaguar’s new Series 3 V12 E-Type. A mag wheel disintegrated at over 140 mph, and the XJ13 was virtually destroyed in the ensuing crash. Dewis, fortunately, was not badly hurt, and the car was eventually rebuilt and is today proudly displayed at the Jaguar museum when not on the road for special appearances, the most recent, at this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Norman Dewis, who has arguably driven more Jaguars than any man in history, remains unequivocal about his special Sunday test car. “It’s a one-off. I mean, I look at that car as a Picasso painting. It’s so beautiful,” he says, adding with his impish smile, “and I loved driving it.”

Photo: Tim Considine